eBook - ePub

Baseball on the Prairie

How Seven Small-Town Teams Shaped Texas League History

- 243 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

At the close of the nineteenth century, railroad expansion in Texas at once shrank the state and expanded opportunities, including that of Texas League Baseball. Previously, the major cities monopolized Texas minor-league ball, but with the rails came small-town teams without which the league may have floundered. Sherman, Denison, Paris, Corsicana, Cleburne, Greenville and Temple teams produced some of the Texas League's greatest players and provided unprecedented statewide interest. The 1902 Corsicana Oil Citys was one of the most successful teams of the time, claiming the second-best winning percentage and baseball's most lopsided victory, 51-3 over Texarkana's Casketmakers. In its only year in the league, Cleburne won the league championship and team owner Doak Roberts discovered the great Tris Speaker. Kris Rutherford pieces together the Texas League's early days and the people and towns that made this centuries-old institution possible.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Baseball on the Prairie by Kris Rutherford in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

TEXAS: NO LEISURE ON THE NEW FRONTIER

Pioneers migrating to North Texas in the late 1830s hadn’t heard of baseball; in fact, neither had most Americans. People in the Northeast played a primitive form of the sport known as “town ball” or “round ball”; however, the rules varied from place to place, and most considered the game little more than a passing fad. After all, leisure time remained elusive in nineteenth-century America. The thought of wasting precious spare time on a game seemed unthinkable to most. For those moving to the new Republic of Texas, on the other hand, spare time simply didn’t exist.

While some saw hope and opportunity on the western frontier, most Americans placed their faith in the Industrial Revolution. Just a generation earlier, the War of 1812 revealed the country’s flawed manufacturing and transportation systems, and industrial advancement had since spread rapidly. Eli Whitney’s 1793 cotton gin offered an early glimpse of technology’s potential, and by the first half of the nineteenth century, this simple invention sparked frenzied economic growth. Southern cotton plantations provided northern textile mills raw material for mass production, and the seemingly limitless crop increased demand for cotton-based goods, a supply-and-demand chain bringing tremendous advancement in manufacturing technologies. As the cotton industry grew, engineers adapted textile technologies to other industries, and manufacturing grew exponentially.

The economic health of the new industrial sector required an efficient distribution system. In the early 1800s, transportation infrastructure like the Erie Canal cut shipping time and cost, but industrial leaders recognized the nation’s economic future when the first stretch of railroad opened between Baltimore and Frederick, Maryland. The railroad age arriving, by 1831, America stood on the cusp of a major societal shift. Manufacturing would soon be just as important as agriculture, and the diversity would improve all aspects of life. Americans looked forward to a mobile society and quality, reasonably priced goods made by skilled workers who commanded higher wages and shorter workweeks. Still, the farther west one traveled, the less one felt the Industrial Revolution’s impact. Socioeconomic change turned much slower than the wagon wheels headed for Texas.

Americans enjoyed leisure activities like theater and dancing long before the Revolutionary War, and as the nineteenth century neared its midpoint, they demanded even more amusements. City planners set aside green spaces for parks, and activities like kite flying, festivals and outdoor games grew popular. In time, town ball became more organized, and standardized rules helped the game grow. Other sporting competitions like boxing, horse racing and cockfighting attracted both spectators and gamblers. Increased disposable income meant people were willing to pay for entertainment, and recreation in the eastern United States commercialized. On the other hand, no elaborate opera houses, manicured parks or grand ballrooms operated on the prairies of North Texas. A wild frontier greeted settlers, with nothing except backbreaking hard work to tame it. Even hunting, a sport for many back east, became a basic means of survival on the new frontier.

While their new home offered few comforts, most early Texans already hailed from undeveloped areas of the country. Many migrated from farms in Kentucky and Tennessee, while others arrived from the rural Midwest. Still, as the pioneers crossed the Red River or traveled northward from Galveston, they found a land nothing like that they left behind. A tall-grass prairie rooted in black soil as fertile as any in the United States covered North Texas. The blackland prairie could have easily supported a lucrative cotton industry, but few settlers owned slaves, leaving them to grow less labor-intensive crops like corn and wheat. Regardless, the new Texans did not lack optimism. The Red River and its tributaries provided plenty of water. Wildlife like buffalo, white-tailed deer, bobcats, quail and other commercially valuable species filled the prairies. Settlers found timber along creek banks and in the “Big Thickets” breaking up the prairie. Many found local Indians eager to trade. The settlers marveled at the vast resources Texas offered.

Texas’s seemingly unlimited potential did not come without peril. Fires in the tall-grass prairie devastated families. Indian tribes like the Wichita grew hostile toward the invaders of their sacred territory. The oppressively hot summers overwhelmed even those accustomed to a southern climate, and crops withered in periods of drought. Early North Texans faced many of the same challenges as those in pre-colonial New England, with climate, Native Americans and ignorance of local agricultural methods detrimental to daily life. Still, new Texans arrived regularly. Soon the trickle of pioneers became a steady flow.

As North Texas grew, small communities formed. People with common heritage banded together in settlements like Kentuckytown in Grayson County, while others congregated around transportation routes like the Trinity River at present-day Dallas. Most communities, though, developed out of socioeconomic need. People met in central locations to share ideas and obtain the few goods available for survival. Before long, stores and trading posts emerged, and settlers built homesteads nearby. Economies grew around these new communities, and they became important centers of politics, commerce and social growth.

Soon, the harsh realities of the frontier began to ease. By statehood in 1845, treaties with Native Americans reduced threats of attack, and tribes moved to reservations or across the Red River into present-day Oklahoma. Intense farming broke the prairie’s dense sod, and land routes from Galveston and Jefferson brought wagons and a steady supply of dry goods. Mercantile businesses attracted saloons and brothels as enterprising individuals sought to provide diversions for local residents and travelers. These establishments represented a culture later romanticized in novels, movies and music and provided Americans a vision of Texas as a rugged, lawless frontier. More importantly, though, they represented the first commercial recreation ventures in North Texas.

Those who clung to the Puritan values and religious convictions of the Northeast likened Texas’s limited recreation opportunities to the work of the devil. Promoting idleness and detracting from the work ethic, many considered the gambling, prostitution and drunkenness in their growing communities morally reprehensible. Even as more acceptable forms of recreation arrived, some settlers resisted the leisure pursuits shaping Texas culture. Most, though, took little notice and continued to carve out an agriculture-based frontier life. Only an enterprising few saw the growth of recreation for what it truly represented—opportunity.

CHAPTER 2

THE CIVIL WAR, RECONSTRUCTION AND BASEBALL: DIVISION AND DIVERSION

Suddenly there was a scattering of fire, [of] which three outfielders caught the brunt; the center field was hit and was captured, left and right field managed to get back to our lines. The attack…was repelled without serious difficulty, but we had lost not only our centerfield, but…the only baseball in Alexandria.

—George A. Putnam, Union soldier

The first baseball game in Texas remains undocumented. George Putnam’s account of his Civil War experience near Alexandria, Louisiana, took place well east of the Texas border, but his passage supports what many believe—that Union soldiers largely introduced modern baseball to the South during the Civil War. While some Rebel soldiers from port cities had learned portions of the game from northern seamen before the war, most of the Confederate exposure to baseball came from watching their enemies play the game in encampments and inside prisoner of war camps. Diaries of Union prisoners at Camp Ford near Tyler speak of baseball being played in the camp, with the soldiers forming a ball from a piece of cork wound in blanket thread and covered in leather. The Rebel guards must have been intrigued at the competitive spirit the contests brought out in their prisoners’ otherwise bleak lives. Even though crude forms of the game had been played in the South for some time, the Rebels marveled at the northern game’s refined rules and skilled positioning of players.

Some of the same guards from Camp Ford may have participated in Texas’s first recorded baseball game on April 21, 1867. The Houston Stonewalls celebrated the anniversary of Texas’s independence from Mexico by defeating the Galveston Robert E. Lee’s 35–2 on the San Jacinto battlefield. Regardless of when or how the game arrived in the state, however, it is clear that soon after the Civil War, the same “base ball” fever sweeping the nation arrived in Texas.

The northern tier of Texas counties voted against secession leading up to the war, but when hostilities began, most men broke ranks with the popular vote and joined the Confederate cause. Charles William Batsell, a twenty-two-year-old Grayson County resident whose father owned just one of the county’s two hundred slaves, enlisted in the Sixteenth Texas Cavalry under Fitzhugh’s command. After mustering at Clarksville, his company soon stationed at Little Rock, Arkansas, and saw its first combat at the Battle of Cotton Plant along the White River. When Rebel commanders ordered the cavalry dismounted, Batsell joined “Walker’s Greyhounds,” an infantry division nicknamed for its ability to march long distances on short notice. Batsell and his unit crisscrossed southern Arkansas and Louisiana for nearly three years, taking part in the Vicksburg and Red River Campaigns and the Camden Expedition. With Union troops scattered throughout both Arkansas and Louisiana and combat sporadic, it is likely that Batsell witnessed baseball being played during raids like those described by George Putnam. Whether or not Southerners attempted to mimic the game in their own camps remains unknown.

Will Batsell held little interest in the rural lifestyle. An enterprising young man, he saw a future in goods and services and, while assigned to the Confederate Commissary, gained valuable experience in inventory and distribution channels. Returning to North Texas after the war, Batsell spent two years as postmaster in Kentuckytown before moving to Sherman, the fledgling county seat a dozen miles northwest. Will Batsell found Sherman a ramshackle town suffering the same economic hardships plaguing the rest of the South. With supplies limited and their Confederate money now worthless, local residents faced a bleak future as Reconstruction began. Will, on the other hand, clung to a positive vision.

With the states once again united, the technology and transportation systems of the Northeast slowly made their way to Texas. Texans looked forward to railroad and manufacturing jobs, reduced work hours and more leisure time. As the country closed its most turbulent decade, Will Batsell foresaw a prosperous Sherman steeped in commerce and culture, with recreation and transportation fueling both.

While Will Batsell’s unit patrolled the western theater, Leonidas Linville Maughs engaged in some of the Civil War’s fiercest fighting in Tennessee and Georgia. Rebellion ran in Maughs’s bloodlines. The son of a Missouri physician who owned six slaves, Maughs’s family lineage dated to seventeenth-century Virginia, and several of his ancestors fought for the Continental army during the American Revolution. With the onset of the Civil War, Maughs, a store clerk in his Missouri hometown, quickly joined the Rebel cause, enlisting in Captain Hiram Bledsoe’s Missouri Battery. He first saw action at Fort Pillow, Carthage, Wilson’s Creek and Pea Ridge west of the Mississippi but moved to Chattanooga by late 1863. Maughs fought at the Battle of Chickamauga, where some news accounts credited him with killing Union general and Civil War poet William Haines Lytle. Despite his act of valor, Maughs probably didn’t feel a sense of achievement, as even his fellow Rebel soldiers mourned the death of the well-known general, placing a wreath over his body and reciting his poetry in his honor.

As the war drew to a close, Maughs remained in Georgia, eventually wounded and taken prisoner at the Battle of West Point. Transferred to Nashville with other prisoners, the Confederate surrender at Appomattox hastened his released after only two weeks. Assigned the rank of major upon discharge, admirers referred to him as “Major Maughs” for the remainder of his life.

Unlike Batsell, Leonidas Maughs did not return home at war’s end. Instead, he became a lawyer in Corinth, Mississippi, just a few miles south of Shiloh, the site of one of the war’s bloodiest battles. By 1876, he relocated to the young railroad town of Denison, Texas, where he served as superintendent of the local gaslight company, as well as a lawyer and postmaster. Major Maughs represented Denison in a number of capacities and took great interest in the future of his adopted city. Like Will Batsell, Maughs recognized the growing demand for leisure and recreation. By 1890, he helped found the Denison Rod and Gun Club, was named its first president and traveled with fellow members into newly settled Oklahoma on quail hunts. Likewise, he took great interest in the amateur baseball games regularly played in Forest Park, contests often pitting Denison against Sherman, its neighbor just nine miles south.

Honey Grove and Bonham. Commerce and Wolfe City. Petty and Roxton.

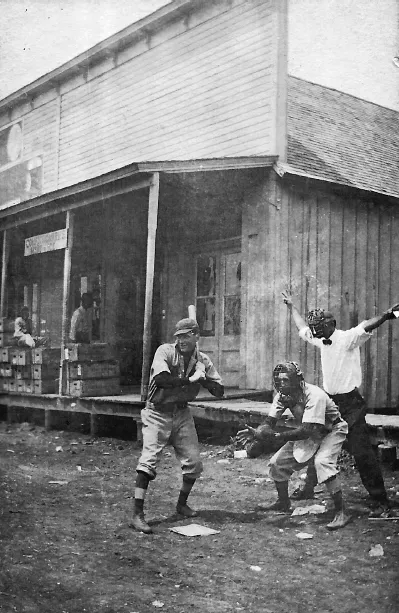

None of these North Texas towns are known for baseball, but at one time, each boasted its own traveling “Nine” town ball club. Although not the original town ball played in the Northeast before the Civil War, the modified game proved a highly popular form of local entertainment. Entire communities often turned out for a town ball game, the players dressed in elaborate uniforms any major leaguer would wear with pride. A rough bare lot or pasture on the outskirts of town fit the bill as a ball field, most often ending in a high-scoring, error-filled game. Still, rivalries became intense as each community supported its homegrown talent. Animosity between communities grew as players, coaches, umpires and “rooters” frequently brawled after disputed plays. A team tiring of its competition might place an announcement in the newspaper seeking new opponents, sometimes publicly challenging a specific community to a ballgame. More often than not, the challenged team accepted, setting off a war of words filling newspapers for a week. The games seldom lived up to their billing, and the newspaper editors who hyped them most often buried the results in a single sentence between advertisements for manly footwear or medicinal concoctions.

A game of town ball played in Brookston (Lamar County), circa 1910. Courtesy of Phillip Rutherford.

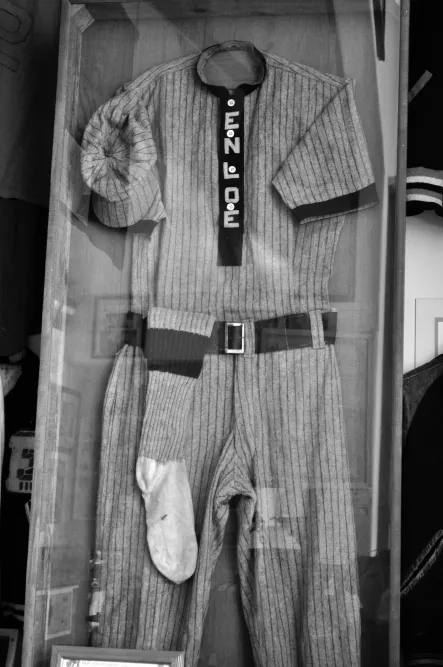

Early Enloe (Delta County) uniform typical of those worn by town ball teams. Karen Rutherford photo.

Despite the allure of town ball, visiting teams almost always played at a disadvantage. Transportation via horses, mules and wagons made travel to even nearby towns time consuming, and the heat, rough ride, thirst and hunger might defeat a team before it even arrived at the ball field. Rosters shifted depending on how much work lay in the fields, no organized schedules existed, teams split gate receipts (if any) without accounting and rules seemingly changed mid-game. A man willing to serve as umpire placed his life in the hands of a crowd easily turned hostile and offered rulings in favor of the home team as much out of fear as fairness. A shellacking on a dusty diamond often added humiliation, and players might return home vowing to never play the game again. But baseball held a seemingly universal allure. Many small towns clung to their teams for decades, sometimes fielding two or even three teams if local talent warranted. Still, with few exceptions, these town ball teams normally stayed close to home and local competition. In the mid-1870s, though, the railroad’s arrival changed baseball in the Lone Star State forever.

Early Texas settlers relied on primitive transportation. Steamboats only navigated rivers near the coastal region, although they could access as far inland as the port of Jefferson via the Red River from Louisiana. In time, the Red River provided easy transportation to North Texas, but until then, the Great Raft, a centuries-old dam of driftwood, fallen trees and other debris, formed a blockade to all navigation north of present-day Shreveport. So with waterway travel limited, most transportation relied on mule and oxen power. This inherently inefficient, expensive and unreliable shipping method lay at the mercy of weather that often made crude wagon trails muddy and impassable.

The Texas Congress authorized construction of a railroad within months of winning independence from Mexico, but it wasn’t until 1851 that the state’s first line began to take shape. Spearheaded by General Sidney Sherman, the Buffalo Bayou, Brazos and Colorado Railroad opened a twenty-mile line between Harrisburg and Stafford two years later. By 1856, the Galveston and Red River Railway opened its own twenty-five-mile route in the Houston area and soon changed its name to the Houston and Texas Central (HTC), with plans to lay track all the way to the Red River in Grayson County. By the outset of the Civil War, Texas boasted nearly five hundred miles of rail line, most of it in the populated southeast coastal area.

The Civil War brought most railroad construction to a halt, and with materials in short supply, existing rail fell into disrepair. Railroad companies took some lines out of service for the war’s duration, but construction and repairs resumed after the South surrendered. The HTC led the way, continuing northward and reaching Corsicana by 1871. Two years later, the railroad completed its run through Dallas to the Red River nearly two decades after initial construction began. New railroads soon connected Houston, San Antonio and Austin. Meanwhile, the Texas and Pacific Railroad, a southern transcontinental route, stretched a line from Texarkana to Dallas/Fort Worth via Tyler, as well as a northern route from Sherman across Fannin County toward Texarkana. The Missouri, Kansas and Texas, historically known as “the Katy,” crossed into Grayson County from the Red River, and the Cotton Belt line stretched through east-central and north Texas. By the late 1880s, railroads connected all of the state’s major cities. Small communities along the routes prospered. In many cases, the railroad itself formed communities at junctions, machine yards and switch stations. Corsicana, Temple, Denison, Cleburne and Terrell all owed their existences to the railroads, and the industry employed most of each community’s citizens. For some Texas settlements, though, the arrival of the railroad signaled their demise. Surveyors planned routes based on finances, topography, land values and potential for development. Aside from county seats, rail c...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue

- 1. Texas: No Leisure on the New Frontier

- 2. The Civil War, Reconstruction and Baseball: Division and Diversion

- 3. Professional Baseball: Faith and Failure in Texas

- 4. Sherman, Denison and the Fenceless Frontier

- 5. 1895: The Texas League’s First Foray into a Second-Tier City

- 6. 1896: A Rivalry Cut Short

- 7. Paris: Stepping up to Save the Circuit

- 8. 1897: The Increasing Railroad Influence

- 9. 1902: The Interurban and a Team for the Ages

- 10. 1903: Competitive Balance

- 11. 1904: Small Cities Sandwich the League

- 12. 1905: A Shorter Jump

- 13. 1906: New Cities, New Legends

- 14. 1907: The Small Market’s Last Stand

- Afterword

- Bibliography

- About the Author