- 147 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Join journalist and historian Jim Wise as he follows Sherman's last march through the Tar Heel State from Wilson's Store to the surrender at Bennett Place. Retrace the steps of the soldiers at Averasboro and Bentonville. Learn about what the civilians faced as the Northern army approached and view the modern landscape through their eyes. Whether you are on the road or in a comfortable armchair, you will enjoy this memorable, well-researched account of General Sherman's North Carolina campaign and the brave men and women who stood in his path.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access On Sherman's Trail by Jim Wise in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Goldsboro, March 23

Striding triumphant, the great army looked ridiculous.

Some soldiers laughed, some swore, some made futile attempts to form ranks. There went one in a tall silk hat, and another in a lady’s sunbonnet. Some had horses, some had donkeys, most were on foot and not too many of them had shoes.

They were part of an army, though, a big one—maybe ninety thousand or so in all—veteran and victorious. In seven weeks, they had marched 425 miles through rain and muck, leaving the enemy’s country in a swath of ruin 40 miles wide. Two days before, they had repulsed the best effort of a ragtag force that was the best their enemy could muster to block them. They had accomplished “one of the longest and most important marches made by an organized army in a civilized country,” according to their general.

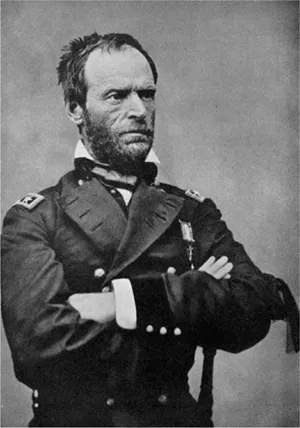

That general was William Tecumseh Sherman, “Cump” to his friends, “Uncle Billy” to his troops and the devil incarnate to generations of Southerners to come.

It was Thursday, March 23, 1865. Sherman’s army had reached Goldsboro, North Carolina, a railroad junction town that had been his goal since leaving the Georgia coast on the first of February. South Carolina, the “hellhole of secession,” was punished: Columbia, its capital, was burned; Charleston, where Rebels fired their first shot, was surrendered; the countryside, through which Sherman’s men passed, was stripped practically bare.

Since the first of March, Union elements had been active in North Carolina. Sherman himself crossed the state line on the eighth, and by that time he had let the army know he wanted this state to feel a lighter touch. To his cavalry commander, Judson Kilpatrick, he wrote:

General William T. Sherman. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Deal as moderately and fairly by North Carolinians as possible, and fan the flame of discord already subsisting between them and their proud cousins of South Carolina.1

Major General Henry W. Slocum, commanding Sherman’s left wing, echoed his superior’s sentiments. From Sneedsboro, North Carolina, on the Pee Dee River just above the South Carolina line, he issued a general order:

All officers and soldiers of this command are reminded that the State of North Carolina was one of the last States that passed the ordinance of secession, and that from the commencement of the war there has been in this State a strong Union party…It should not be assumed that the inhabitants are enemies to our Government, and it is to be hoped that every effort will be made to prevent any wanton destruction of property, or any unkind treatment of citizens.2

Nevertheless, the U.S. Army had left a trail of ransacked homes, dead livestock and destitution from Monroe to Goldsboro. Writing from Fayetteville, a correspondent of the Hillsborough Recorder reported:

The Yankees arrived on Sunday [March 12] morning, and have nearly destroyed both town and country…Our house and many others were burned, and every thing destroyed. Even the negroes have been robbed and starved. As to valuables, nothing is safe in their sight. 3

Perhaps, then, it was not surprising that the anticipated Union sympathies were yet to be found. Major George W. Nichols, a Sherman aide, wrote that the Northerners were “painfully disappointed…The city of Fayetteville was offensively rebellious.”4

However destructive their trip or unwelcoming the towns along the way, the army had come through, and coming into Goldsboro in an informal review, it showed the effects and results of seven weeks on the road.

“They are certainly the most ragged and tattered looking soldiers I have ever seen belonging to our Army,” artillery Major Thomas W. Osborn wrote in his journal.5

It is almost difficult to tell what was the original intention of the uniform. All are very dirty and ragged, and nearly one quarter are in clothes picked up in the country, of all kinds of gray and mud color imaginable.

Nichols observed,

We found food for infinite merriment in the motley crowd of “bummers.” These fellows were mounted upon all sorts of animals, and were clad in every description of costume; while many were so scantily dressed that they would hardly have been permitted to proceed up Broadway without interruption. Hundreds of wagons, of patterns not recognized in army regulations, carts, buggies, barouches, hacks, wheel-barrows, all sorts of vehicles, were loaded down with bacon, meal, corn, oats and fodder, all gathered in the rich country.6

About the same time, Sherman’s Confederate counterpart, General Joseph E. Johnston, was about fifteen miles to the west, outside Smithfield.

“Troops of the Tennessee army have fully disproved slanders that have been published against them,” he wrote to his superior, General Robert E. Lee, in Virginia.

The moral effect of these operations has been very beneficial. The spirit of the army is greatly improved and is now excellent. I am informed by persons of high standing that a similar effect is felt in the country.7

Johnston must have known he was whistling in the dark. By this time, he was well acquainted with his opponent. The summer before, he had faced Sherman in north Georgia in an attempt to stop the Union advance from Chattanooga to Atlanta. Repeatedly outflanked, Johnston was relieved of command by Confederate President Jefferson Davis. Davis replaced Johnston with General John Bell Hood, who proved to be even less effective. Sherman occupied Atlanta in September. Johnston assumed retirement in Columbia, South Carolina.

Sherman had left an ashen Atlanta in November, marched through Georgia and occupied Savannah, on the coast, in time to offer the city to U.S. President Abraham Lincoln as a Christmas present. Meanwhile, Sherman’s superior, Union General Ulysses S. Grant, was in an entrenched standoff with Lee around Richmond and Petersburg, Virginia. Figuring that a decisive defeat of Lee would put an end to the rebellion once and for all, Grant wanted Sherman to put his army on ships, sail north and join him.

Sherman had another idea. Rather than going north by sea, he wanted to go by foot, exacting revenge on South Carolina “as she deserves”8 and further dispiriting the Confederate home front. Desertions, he knew, were all but decimating Lee’s army, as soldiers headed home in response to plaintive letters from suffering and frightened loved ones. A land campaign would also sever more of what few supply lines Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia had left.

Grant agreed. Sherman meant to set out in early January, but the heavy rains that would beset his advance almost every step of the way north had the wide Savannah River in a torrent that wrecked a pontoon bridge and led him to delay a month for better weather. Meanwhile, on January 15, a Union force captured the Confederate Fort Fisher, which had guarded the Cape Fear River’s mouth in North Carolina and the Wilmington port that had been the blockade runners’ last resort.

Sherman finally left Savannah on February 1, with sixty thousand men and twenty-five hundred wagons in several columns that stretched as much as ten miles along several different roads. Two days later, at Hampton Roads, Virginia, a four-hour peace conference between the South and the North came to naught. Meeting scant resistance from the scattered Confederate forces under Lieutenant General William Joseph Hardee—a former West Point superintendent who was recognized by both sides as a master of battlefield tactics—Sherman moved rapidly north toward Lee. Recognizing the threat, Lee, himself just appointed the Confederate commander in chief, summoned Johnston, who had by then removed to Lincolnton, North Carolina, to assemble what troops he could to “drive back Sherman.”9

After some effective delaying actions, Johnston attacked on March 19 near the village of Bentonville, twenty miles west of Goldsboro. His plan was sound, and his men fought well, but the vastly superior Union numbers proved overwhelming and, under cover of darkness on the night of the twenty-first, he withdrew.10

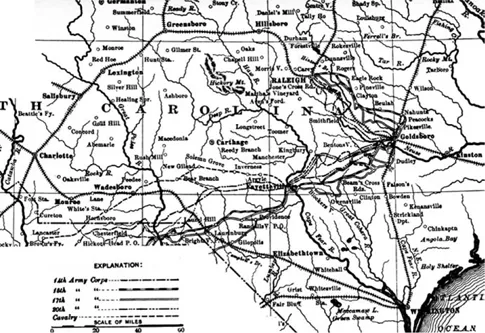

A map of central North Carolina, with the routes of Sherman’s corps. From Osborn, The Fiery Trail.

“The Rebels contest every foot of ground with extraordinary pertinacity,” wrote Nichols, the Sherman aide, following the Bentonville battle. “More tenaciously than the occasion seems to require.”11

On the twenty-third, Johnston had less than twenty thousand men left in fighting condition. Some had retreated as far as Chapel Hill, the state university village fifty miles northwest. Some townsfolk met them with whiskey, which was no doubt welcome, but their presence strained resources that were already depleted.

“Some of my neighbors have been constrained to furnish inconvenient supplies of corn, as well as long forage,” university president David L. Swain wrote. “We will all breathe more freely when it shall be ascertained that they are all through.”12

Sick and having found himself left behind during the Bentonville retreat, Confederate Private Arthur P. Ford managed to reach his unit and report to its surgeon.

At eight o’clock on the morning of the 23rd I was driven in an ambulance to a railway station and put with a lot of sick and wounded men on a train for Greensboro. I had had nothing to eat since about noon the day before, and when we got to Raleigh I got off and went to a near-by little cottage, where I saw a woman at the door, and told her that I was really very sick, and very hungry, and begged her for something to eat. I had not a cent of money. She told me pathetically that she had fed nearly all she had to the soldiers, but had a potato pie, and if I could eat that I would be welcome to it. I took it gratefully and it was the nicest potato pie I ever saw.13

Near Chapel Hill, in the colonial town of Hillsborough, the war had seemed distant. Local boys were in the fight, but events had stayed far away in Virginia or Georgia or Tennessee. On March 22, the hometown Recorder’s front page led with a profile of the Russian Field Marshal Suwarrow and a eulogy for the Philadelphia banker Stephen Girard before reporting the reprieve of a condemned Virginian deserter.

Well migh...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Chapter One: Goldsboro, March 23

- Chapter Two: Moving In

- Chapter Three: Fighting Through

- Chapter Four: Wrapping Up

- Appendix 1: Sherman’s Trail—A Suggested Itinerary

- Appendix 2: Useful Names and Numbers

- Notes

- Bibliography