- 191 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Join Charleston historian Doug Bostick as he traces the political turmoil of 1860 and early 1861, when the firebrands of secession in Charleston were pushing the South to act together in a decisive way. The Union Is Dissolved chronicles the face-off between professor and student--Robert Anderson and Pierre G.T. Beauregard--and the firing on Fort Sumter, signaling the beginning of the American Civil War. Featuring many historical images and first-person accounts found in period newspapers and family papers, this fascinating volume offers a concise introduction to our nation's greatest struggle.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Union is Dissolved! by Douglas W Bostick in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

THE PRINCIPLES OF

SELF-DETERMINATION

Secession is not a concept of the nineteenth century. The use of force to hold a political union is almost as old as man himself. Interestingly, almost all the attempts to secede have met with failure, in many cases, with disastrous results.

In the fourth century BC, the city-states of Melos and Mytilene attempted to secede from the Athenian League. The revolt was over heavy taxes imposed by Athens. The revolt was put to bed by a brutal war, which proved a lesson to the other city-states. Later, Rome dealt with many attempts through its history of rule.

In the modern era, the Dutch revolt against the Spanish empire initiated sixty years of war. The struggle of Scotland to gain independence from England foreshadowed the events in America centuries later. The Scots battled for five hundred years and finally ended with the Act of Union in 1707. The Disarming Act of 1756 revoked the Scots’ right to bear arms. It also banned the use of bagpipes and the wearing of tartans. The Scottish quest for independence can be traced back to 1297–1320 and the Declaration of Arbroath, which stated:

So long as there shall be but one hundred of us to remain alive we will never give consent to subject ourselves to the dominion of the English. For it is not glory, it is not riches, neither is it honor, but it is freedom alone that we fight and contend for, which no honest man will lose but with his life.

One British officer, known as “Butcher Cumberland,” laid waste to the Scottish Highlands, not unlike the march of Sherman to the sea in Georgia.

Of course, another long-standing story of independence is the struggle of Ireland. The battle for Irish secession has lasted for almost four hundred years and is still not fully resolved.

The great irony, of course, of the furor over the secession movement in America is that the creation of the very government that fought to prevent secession was born of secession. That fact was not lost on the British when the North–South conflict emerged in America. “The right of a people by popular consent to secede from a larger nation or confederation when the people believed it no longer served their needs and interests” is the story of the American Revolution. One British scholar wrote, “It is startling to realize that Lincoln did not believe in the principle of self-determination of peoples…Lincoln fought against them with more determination than any British Prime Minister fought against Ireland.”

The idea of secession was born in America, though, long before 1860. Massachusetts threatened to secede four times in the history of the young country: over state debts after the Revolution, after the Louisiana Purchase by Jefferson, during the War of 1812 and finally on the annexation of Texas. Unlike Lincoln, Jefferson acknowledged the right of secession if that was the will of Massachusetts.

When ratifying the United States Constitution, Rhode Island, New York and Virginia all retained the right to leave the United States if needed. The Virginia Act, approved on June 26, 1788, stated: “In their name and on behalf of the people of Virginia, declare and make known, that the powers granted under the Constitution, being derived from the people of the United States, may be resumed by them, whenever the same shall be perverted to their injury or oppression.”

As a result of the War of 1812, delegates from Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Vermont and New Hampshire met in the Hartford Convention of 1814 to discuss secession. They wanted to change the Constitution to improve states’ rights. However, the war ended soon and the movement by the Federalist Party faded.

CHAPTER 2

THE FATHERS OF SECESSION

Thomas Cooper was born in 1759 in Westminster, England. His early life was one of privilege. He attended but dropped out of Oxford University and married while still a teenager. Still, he continued his studies of law and medicine. After a bitter experience in British politics, he left England for America in 1793.

He first settled in Pennsylvania and was an outspoken critic of President John Adams. He taught at Carlisle College and the University of Pennsylvania before accepting a teaching position at South Carolina College in 1819. In 1821, Cooper was elected as the second president of the College, a position he would hold for twelve years.

Active in politics, Cooper took particular exception to protective tariffs. In a speech in Columbia, he insisted, “If he [Northern manufacturers] cannot make goods as cheap and as of good quality, is that a reason why his deficiencies should be made good out of our pocket, by compelling us to pay exorbitant prices?” He asserted that Congress had the right to regulate commerce but had no right to legislate protective tariffs.

He concluded the speech by saying:

I have said, that we shall ere long be compelled to calculate the value of our union; and to inquire of what use to us is this most unequal alliance? By which the South has always been the loser and the North always the gainer? Is it worth our while to continue this union of states, where the North demand to be our masters and we are required to be their tributaries? Who with the most insulting mockery call the yoke they put upon our necks the AMERICAN SYSTEM! The question is however fast approaching to the alternative, of submission or separation.

The secession movement thus began in Columbia, South Carolina, in the 1820s.

Despite Cooper’s pontifications and many protests, Congress, in 1828, passed what was called the Tariff of Abominations. Even though import duties were increased to 50 percent, total tax revenue decreased, as people ceased buying foreign goods. Cooper’s writings and speeches had a marked impact on two men: Robert Barnwell Rhett, a young state legislator from Walterboro, and John C. Calhoun, the vice president of the United States in 1828.

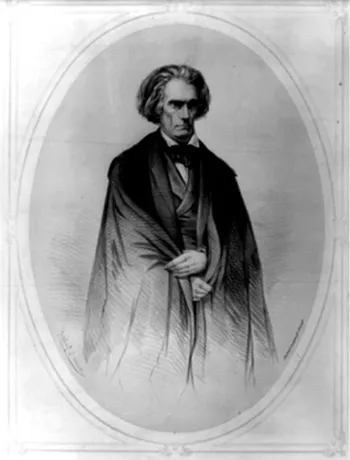

The 1828 tariff act forever changed Calhoun’s political views. In an essay entitled “The South Carolina Exposition and Protest,” Calhoun asserted that states could address their issues with the federal government through nullification, essentially saying that individual states could nullify actions of the government that they deemed unconstitutional.

Though Calhoun was seen previously as a strong “nationalist,” politicians now screamed that he was a “sectionalist.” A good friend and founder of the Charleston Mercury, Henry Pinckney, countered that he and Calhoun were not sectionalists, writing, “We have only changed from being friendly to a system we once imagined would be ‘national,’ to the opponents of a system which we are now convinced is ‘sectional’ and ‘corrupt.’” Across South Carolina, citizens formed State Rights and Free Trade Associations.

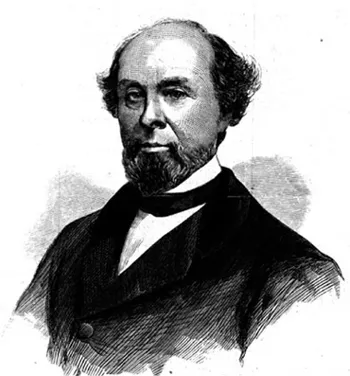

Rhett was a disciple of the writings of Cooper and an ardent supporter of Calhoun. In an Independence Day speech in 1832, Rhett argued, “What sir, has the people ever gained, but by Revolution?…What sir, Carolina has ever obtained great or free, but by Revolution?…Revolution! Sir, it is the dearest and holiest word, to the brave and free.”

Robert Barnwell Rhett was referred to by some as the “Father of Secession.” Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

South Carolinian John C. Calhoun wrote the theory of nullification. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

On November 24, 1832, delegates to a South Carolina Convention declared the Tariff Acts of 1828 and 1832 to be “null” and “void.” It was announced that, effective February 1, 1833, federal duties would no longer be collected in South Carolina.

President Jackson immediately responded by reinforcing the federal garrisons at Fort Moultrie and Castle Pinckney. General Winfield Scott was placed in command and Jackson shipped five thousand muskets to the arsenal at South Carolina. Jackson was quoted as saying, “We shall cross the mountains into…South Carolina with a force, which joined by Union men of that State, will be so overwhelming as to render resistance hopeless.”

Calhoun resigned as vice president but continued in Washington as a senator from South Carolina. Rumors were that Jackson had decided to arrest Calhoun for treason. On December 10, 1832, Jackson issued the Proclamation to the People of South Carolina and reiterated his views on federal rule. Additionally, Jackson sent a bill to Congress to force the collection of tariffs in South Carolina.

As the Senate considered the bill, the Calhoun–Daniel Webster debates were most heated. When the bill came up for a vote, all Southern senators, with the exception of John Tyler, walked out of the chamber in protest.

South Carolina began preparations for a federal invasion. The General Assembly voted to spend $400,000 for defense and authorized the governor to call out the militia. On December 26, Governor Robert Hayne issued a call for volunteers and twenty-five thousand men stepped forward. Everyone on both sides was making final preparations for war.

In Washington, Henry Clay and Calhoun were holding secret meetings seeking a resolution. The meetings produced a compromise tariff bill that both men could support. The new bill provided that tariffs would be reduced in steps over nine years. Calhoun was pleased with the outcome. South Carolina had declared a bill to be “null” and “void” and the bill was replaced.

More radical politicians, like Cooper, wanted to continue resisting Jackson, but Calhoun and Rhett favored the compromise. Rhett did, however, agree that he would be happier with the formation of a Southern Confederacy. Knowing that nothing was permanently resolved and recognizing that the principle of protectionism was still intact, he knew that the fight would simply continue.

CHAPTER 3

LINCOLN IS ELECTED

The issues of states’ rights and protective tariffs never did fade after the 1830s. The South understood that its political influence was receding as more states were admitted to the Union. The expansion of slavery in the western territories was a central issue. The South wanted slavery to be assured in these new territories, but Northerners wanted the new territories and states to be able to decide the issue for themselves. The Southern states were looking for political support from like-minded states in Congress.

In the frequent debates in the Senate over the issue of slavery expansion, Stephen Douglas argued, “I tell you, gentlemen of the South, in all candor, I do not believe a Democratic candidate can ever carry any one Democratic state of the North on the platform that it is the duty of the Federal Government to force people of a territory to have slavery if they do not want it.”

By 1860, cotton was the leading export commodity of the nation. Southern raw goods and agricultural products were much sought after by Northern manufacturers and European interests. The South wanted to trade with Europe, but the protectionist tariffs made European products cost prohibitive. Northern politicians were using the trade tariffs to control Southern raw goods for their own use rather than letting them reach Europe. In short, the Southern states felt that they were being exploited by the Northern majority in Congress.

Author Charles Dickens closely followed the sectional conflict in America and often wrote of the growing tension. In one editorial, he wrote,

The North having gradually got to itself the making of the laws and the settleme...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1 The Principles of Self-Determination

- Chapter 2 The Fathers of Secession

- Chapter 3 Lincoln Is Elected

- Chapter 4 A Southerner in Charge

- Chapter 5 “The Spirit Has Departed”

- Chapter 6 In the Dark of the Night

- Chapter 7 Big Red

- Chapter 8 Horses and Spies

- Chapter 9 The Confederate States

- Chapter 10 The Student Arrives

- Chapter 11 A New President

- Chapter 12 Friends to Charleston

- Chapter 13 “A Sheep Tied”

- Chapter 14 The First Shot

- Chapter 15 Bloodless Victory

- Epilogue

- Bibliography