- 195 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

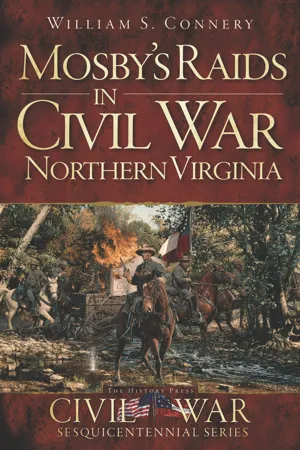

Mosby's Raids in Civil War Northern Virginia

About this book

The fascinating life of Colonel John Singleton Mosby, the Gray Ghost, before, during, and after the Civil War.

The most famous Civil War name in Northern Virginia—other than General Lee—belongs to Colonel John Singleton Mosby, the Gray Ghost. His early life characterized by abuse of childhood bullies, a less-than-outstanding academic career, and even a brief incarceration, Mosby stands out among nearly one thousand generals who served in the war.

Even though Mosby was opposed to secession, he joined the Confederate army as a private in Virginia, and quickly rose through the ranks. He became celebrated for his raids that captured Union general Edwin Stoughton in Fairfax and Colonel Daniel French Dulany in Rose Hill. By 1864, he was a feared partisan guerrilla in the North and a nightmare for Union troops protecting Washington City.

After the war, his support for presidential candidate Ulysses S. Grant forced Mosby to leave his native Virginia for Hong Kong as U.S. consul. A mentor to young George S. Patton, Mosby's military legacy extended far beyond the War Between the States and into World War II. William S. Connery brings alive the many dimensions of this American hero.

The most famous Civil War name in Northern Virginia—other than General Lee—belongs to Colonel John Singleton Mosby, the Gray Ghost. His early life characterized by abuse of childhood bullies, a less-than-outstanding academic career, and even a brief incarceration, Mosby stands out among nearly one thousand generals who served in the war.

Even though Mosby was opposed to secession, he joined the Confederate army as a private in Virginia, and quickly rose through the ranks. He became celebrated for his raids that captured Union general Edwin Stoughton in Fairfax and Colonel Daniel French Dulany in Rose Hill. By 1864, he was a feared partisan guerrilla in the North and a nightmare for Union troops protecting Washington City.

After the war, his support for presidential candidate Ulysses S. Grant forced Mosby to leave his native Virginia for Hong Kong as U.S. consul. A mentor to young George S. Patton, Mosby's military legacy extended far beyond the War Between the States and into World War II. William S. Connery brings alive the many dimensions of this American hero.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Mosby's Raids in Civil War Northern Virginia by William S Connery in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

The Early Years

1833–1860

John Singleton Mosby was born December 6, 1833, at Edgemont in Powhatan County, Virginia, to Virginia McLaurine Mosby and Alfred Daniel Mosby, a graduate of Hampden-Sydney College. His father was a member of an old Virginia family of English origin whose ancestor, Richard Mosby, was born in England in 1600 and settled in Charles City County in the early seventeenth century. Mosby’s mother claimed descent from the Scottish Patriot Rob Roy MacGregor, made famous in Sir Walter Scott’s novel Rob Roy. Mosby was named after his paternal grandfather, John Singleton. So Mosby can be considered a member of the First Families of Virginia (FFVs).

Mosby began his education at a school called Murrell’s Shop. When he started school, his mother insisted that he be accompanied by the house slave, Aaron Burton. After the two-mile walk, Burton was supposed to return home. Mosby convinced him to wait outside at least until noon. When the break came, Mosby was one of the last students out and was horrified to find some of the older boys “auctioning off” Burton. Mosby pounced on the auctioneer, while Burton ran off to home. The boys tried to convince him that they were just joking. Thus began Mosby’s predilection to fight for what he believed was right.

Mosby was also interested and engrossed in reading. When the other children went outside for recess or lunch, he would often stay, reading his favorite books. The story that greatly influenced him was that of Francis Marion, the South Carolinian “Swamp Fox” of Revolutionary War fame. Colonel Marion showed himself to be a singularly able leader of irregular militiamen. Unlike the Continental troops, Marion’s Men, as they were known, served without pay and supplied their own horses, arms and often their own food.

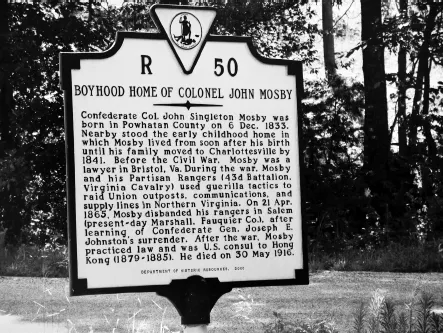

The site of Mosby’s boyhood home in Powhatan County, Central Virginia. Author’s collection.

Marion rarely committed his men to frontal warfare, but he repeatedly surprised larger bodies of Loyalists or British regulars with quick surprise attacks and equally sudden withdrawal from the field. Mosby applied these lessons twenty years later as he fought against a foreign invader. Mel Gibson’s character, Benjamin Martin, in the 2000 movie The Patriot is partly based on Colonel Marion. In this movie, Martin is often referred to by the British as a ghost. Moby’s most popular title is the Gray Ghost.

After two months, Mosby was sent to the Widow Frye’s school. Murrell’s Shop closed because the teacher one day went home for lunch, got drunk and was found in a ditch by the side of the road. The older boys got him back to school. It was his example that led Mosby to abstain from hard liquor for the rest of his life.

His family moved farther west to Albemarle County, near Charlottesville, where the education opportunities were more abundant, with eighteen academies. Because of his small stature and frail health, Mosby was the victim of bullies throughout his school career. The eldest survivor of eleven children (one older sister had died in infancy), Mosby could stay home and read and not be responsible for farm duties. Instead of becoming withdrawn and lacking in self-confidence, the boy responded by fighting back, although Mosby later in his life stated that he never won any fight in which he was engaged. In fact, the only time he did not lose a fight was when an adult stepped in and broke it up.

While Mosby went to a local academy, his sisters were tutored at home by a governess, Miss Abby Southwick from Massachusetts. She was an ardent abolitionist. She was friendly toward Mosby and spoke about the evils of slavery. But he wondered why it was so bad to be a slave. He was very fond of the slaves his father owned, and they seemed to be happy and well cared for.

On October 3, 1850, he entered the University of Virginia, taking classical studies and joining the Washington Literary Society and Debating Union. He excelled in Latin, Greek and literature (all of which he enjoyed), but mathematics was a problem for him. In his third year, a quarrel erupted between Mosby and a notorious bully, George R. Turpin, a tavern keeper’s son who was stouter and stronger than Mosby. When Mosby heard from a friend that Turpin had insulted him, Mosby sent him a letter asking for an explanation—one of the rituals in the code of honor to which Southern gentlemen adhered. Turpin became enraged and declared that on their next meeting, he would “eat him up raw!” Mosby decided he had to meet Turpin despite the risk; to run away would be dishonorable.

On March 29, 1853, the two met, Mosby having brought with him a small pepper-box pistol in the hope of dissuading Turpin from an attack. When they met, Mosby said, “I hear you have been making assertions.” Turpin put his head down and charged. At that point, Mosby pulled out the pistol and shot his adversary in the neck. The distraught nineteen-year-old Mosby went home to await his fate. He was arrested and arraigned on two charges: unlawful shooting (a misdemeanor with a maximum sentence of one year in jail and a $500 fine) and malicious shooting (a felony with a maximum sentence of ten years in the penitentiary). After a trial that almost resulted in a hung jury, Mosby was convicted of the lesser offense but received the maximum sentence. Mosby later discovered that he had been expelled from the university before he was brought to trial. There is nothing to suggest that Turpin, for all of his former violence, was likewise expelled for his notorious past.

While serving time in prison, Mosby won the friendship of his prosecutor, attorney William J. Robertson. When Mosby expressed his desire to study law, Robertson offered the use of his law library. Mosby studied law for the rest of his incarceration. Friends and family used political influence in an attempt to obtain a pardon. Governor Joseph Johnson reviewed the evidence and pardoned Mosby on December 23, 1853. In early 1854, his fine was rescinded by the state legislature. The incident, trial and imprisonment so traumatized Mosby that he never wrote about it in his memoirs.

First known image of Mosby, as a student at the University of Virginia in 1852. Courtesy of the Stuart-Mosby Cavalry Museum.

Aristides Monteiro, a classmate who would later serve as a surgeon in Mosby’s Rangers, said of him, “Of all my University friends and acquaintances this youthful prisoner would have been the last one I would have selected with the least expectation that the world would ever hear from him again.”

After studying for months in Robertson’s law office, Mosby was admitted to the bar and established his own practice in nearby Howardsville. About this time, Mosby met Pauline Clarke, who was visiting from out of town. He was Methodist and she was Catholic, but their courtship ensued. Her father, Beverly Leonidas Clarke, originally from Kentucky, was an active attorney, former member of Congress (serving from Tennessee in 1847–49, the same single term as another Kentuckian, Abraham Lincoln, who was representing Illinois at that time) and well-connected politician. They were married in a Nashville hotel on December 30, 1857. Among their wedding gifts was Aaron Burton, who gladly followed the master of his youth into his new home. After living for a year with Mosby’s parents, the couple settled in Bristol, Virginia, right on the border of Tennessee and close to Pauline’s hometown. They had two children before the Civil War, and another was born during it. They would eventually have eight children: four girls and four boys.

The presidential election of 1860 pitted four candidates against each other. The Republican Party submitted its second candidate, Abraham Lincoln (John C. Fremont had lost to Democrat James Buchanan in 1856). The Democrat Party split between Northern (Senator Stephen Douglas) and Southern (Vice President John C. Breckinridge) candidates. A fourth party, Constitutional Union, built on the ruins of the Know-Nothings, put forth John Bell. In Bristol and the surrounding area, most people supported Breckinridge and Bell. Mosby supported Douglas and on November 6 voted for him by voice, so all his neighbors knew where he stood. Actually, there was no secret ballot at that time. He spoke out against secession, and when an editorial was printed in the Bristol News in January 1861 in support of secession after several Deep South slave states had left the Union, Mosby predicted that secession would mean a long, bloody war, followed by a century of border feuding, and hinted that he would like to be the hangman for any secessionist.

All of this changed on April 12, when Fort Sumter was attacked, and again on April 15, when President Lincoln called for seventy-five thousand volunteers to invade the South. A Virginia Secession Convention had already been meeting for several months in Richmond and had voted twice to remain in the Union. But on April 17, the convention voted for secession, and Mosby, like his later commander, Robert E. Lee, cast his fate with his native state. In December 1860, Mosby had joined a local militia group, the Washington Mounted Rifles, who rarely met. But now their commander, Captain William “Grumble” Jones, called the company to arms, issued Confederate uniforms and told his men to put their home affairs in order. Mosby had joined the Confederate army as a private.

CHAPTER 2

Mosby Goes Off to War

1861

After a few weeks of drilling, Captain Jones got his men on the road to Richmond. The three-hundred-mile journey took eighteen days. At this point, Mosby weighed less than 125 pounds, slouched in his saddle and appeared to be the most unsoldierly one in his unit. Yet as the days rode past, his lungs cleared up, he could breathe freely, he enjoyed eating and he began to gain weight. Describing to his mother his experience of sleeping on the ground, he wrote, “I never before had such luxurious sleeping.” After a few days in Richmond, the command moved several miles north to Ashland. His parents visited him there, bringing a box of food and his slave, Burton, to serve as his body servant. Burton would cook and take care of his horse and bodily needs for the remainder of the war.

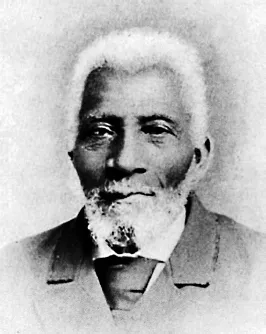

In an interview he gave at the age of eighty-six when he was living in Brooklyn, New York, Aaron Burton was generous in his recollection of Mosby: “I raised Colonel Mosby. I loved him and was with him in all his battles. When the war was over Colonel John told me that I was free and could go and do as I pleased. He is a good man, and was a great fighter.”

After the war, Mosby never denied that slavery was wrong or that it was the root cause of the war, but at the same time, it was important that he at least be regarded as a generous master.

While in camp, Mosby made only two real friends. One was Fountain Beattie, who became one of his Rangers and whom he remained close to his entire life. The other was his commander, Captain Jones. “Grumble” Jones had attended West Point (class of 1848) and served several years with the U.S. Mounted Rifles on the frontier. He came home to Virginia on furlough to marry his sweetheart, Eliza Dunn, on January 13, 1852. Less than three months later, on a voyage to a new assignment in Texas, a storm came up that swept Eliza out of his arms and overboard, where she drowned. He blamed himself for her death, wishing that he could have saved her or drowned with her. He never remarried.

Mosby’s servant Aaron Burton later in life. He attended to Mosby throughout the war. Mosby freed him when the war ended. Author’s collection.

Jones was gruff with his men and insisted that they follow the fundamentals of military training. Mosby had picked a good mentor for his introduction into military life. Jones taught him the importance of vigilance, showed him how to enforce discipline fairly and, by example, demonstrated that the men appreciated efficient administration. Mosby valued Jones’s teaching so highly that, when a friend offered to obtain Mosby an officer’s commission, he declined, preferring to train as a private under Jones. If Robertson had made Mosby a lawyer, “Grumble” Jones was setting him on the path to becoming the Gray Ghost.

On July 1, as Jones’s command was arriving at Bunker Hill in the Shenandoah Valley, Mosby saw for the first time his future commander, Lieutenant Colonel James Ewell Brown (Jeb) Stuart. Just ten months older than Mosby, Stuart weighed 180 pounds, with auburn hair and a full reddish beard. He was another West Pointer (class of 1854), had almost been killed by Cheyenne Indians and assisted Robert E. Lee in the capture of John Brown in October 1859. For Mosby, an aura of Victorian romance surrounded Stuart; he was a romantic cavalier, a brave fighter so gentle that on the western prairie, Stuart collected tiny flowers and feathers of small birds and pressed them into scrapbooks of clippings of cheerful, optimistic poems. Stuart was so unique that Mosby later wrote, “He seemed to defy all natural laws. I did not approach him, and little thought that I would ever rise from the ranks to intimacy with him.”

After just ten days of scouting, Jones’s troops took part in the screening of the Confederate army, allowing General Joe Johnston’s withdrawal from the Valley to reinforce General Pierre G.T. Beauregard’s army, ensconced on the banks of Bull Run in Northern Virginia. Jones’s men remained mainly in reserve, until Union forces ran back in defeat toward Alexandria and Washington City, after the Battle of First Manassas/Bull Run on July 21. Mosby and his companions pursued the fleeing Yankees for six to eight miles, retrieving overcoats, tents, muskets and other items, along with capturing prisoners until dark. He expected the war to be over by the end of the year. Yet in analyzing First Manassas after the war, he argued that the Confederate cause was lost there because its advantage had not been exploited. He thought that if the available cavalry units, including Stuart’s, had been ordered across the Potomac River above Washington City at Seneca Mills in Maryland, they could have moved toward Baltimore, cut communications and isolated Washington and possibly ended the war.

For the next six to eight months, Jones’s Mounted Rifles spent most of their time on patrol and picket duty, often in sight of the enemy capital, Washington City. Just a week after the battle at Manassas, Mosby wrote to Pauline from Fairfax Court House:

We have made no further advance and I know no more of contemplated movements than you do…A few nights ago we went down near Alexandria to stand as a picket (advance) guard. It was after dark. When riding along the road a volley was suddenly poured into us from a thick clump of pines. The balls whistled around us and Captain Jones’ horse fell, shot through the head. We were perfectly helpless, as it was dark and they were concealed in the bushes. The best of it was that the Yankees shot three of their own men—thought they were ours…Beauregard has no idea of attacking Alexandria. When he attacks Washington he will go about Alexandria to attack Washington. No other news. For one week before the battle we had an awful time—had about two meals during the whole time—marched two days and one night on one meal, in the rain, in order to arrive in time for the fight…We captured a great quantity of baggage left here by the Yankees; with orders for it to be forwarded to Richmond.

Generally during the war, both sides deployed cavalry as pickets or guards to serve as a tripwire defense to warn of an approaching enemy force. A line of companies spread across the front, with each company headquarters designated as the reserve and outposts or picket posts of four to six mounted men thrown forward one-half mile. The only one who stayed alert and mounted was the vidette, a man from the outpost positioned one hundred yards toward the enemy. Mosby enjoyed duty as a vidette, much preferring it to camp life, which he considered irksome. At a crossroads in Fairfax County, he would sit alone on his horse from midnight to daybreak, listening to the night sounds of the forest. He ate breakfast with the local people and, on scouts with the company, learned how to set an ambush among the dense pines and, when ambushed, remain calm and aim low.

It was during this time that Mosby had his first real brush with death. He wrote to his wife at the beginning of September:

I received your letter about two days ago and would have immediately replied but was unable to do so until now. I received a fall from my horse one day last week near Falls Church which came very near killing me. I have now entirely recovered and will return to camp this morning which is now about four miles from here [He was convalescing at Fairfax Court House]. I was out on picket one dark and rainy night. There were only three of us at one post. A large body of cavalry came dashing down towards us from the direction of the enemy. Our orders were to fire on all. I fired my gun, started back towards where our main body was. My horse slipped down, fell on me and galloped off leaving me in a senseless condition in the road.

Fortunately the body of cavalry turned out to be a company of our o...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. The Early Years: 1833–1860

- 2. Mosby Goes Off to War: 1861

- 3. A Year of Transition: 1862

- 4. Founding the Partisan Rangers: 1863

- 5. A Thorn in the Side of the Yankees: 1864

- 6. No Surrender for Mosby: 1865

- 7. Mosby’s Postwar Years: August 1865–May 1916

- Appendix I. The Scout Toward Aldie, by Herman Melville

- Appendix II. Mosby’s Recommendation from Jeb Stuart

- Appendix III. Appreciation of Mosby from The Photographic History of the Civil War

- Bibliography

- About the Author