- 147 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The culinary history of Miami is a reflection of its culture--spicy, vibrant and diverse. And though delectable seafood has always been a staple in South Florida, influences from Latin and Caribbean nations brought zest to the city's world-renowned cuisine. Even the orange, the state's most popular fruit, migrated from another country. Join local food author Mandy Baca as she recounts the delicious history of Miami's delicacies from the Tequesta Indians to the present-day local food revolution.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Sizzling History of Miami Cuisine by Mandy Baca in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

THE INGREDIENTS

NATIVE VERSUS NONNATIVE

Miami is a cornucopia of products and flavors. I know you’ve heard that one before, but here’s a closer look at what that exactly means. Did you know that Florida fishermen catch more than 84 percent of the nation’s supply of grouper, pompano, mullet, stone crab, pink shrimp, spiny lobsters and Spanish mackerel?9 Another fun fact is that avocados were once originally called alligator pears because of their rough, hard, green exterior. Lastly, after California, Florida is the largest producer of edible food in the country. Before its incorporation, Miami was extremely rural, and when it came to food, it was all about the ingredients and how to procure them; there were no talks about restaurants, chefs or unique organic farms. There were only a few paved roads, the areas were heavily overgrown and there was a large concentration of wildlife. Charles Featherly, an important early figure for the preservation of farming initiatives and food memories, conducted an extensive farming census of all Dade County’s endeavors. He found the following to be the most prominent and important crops to be grown: tomatoes, beans, grapefruit, oranges, pineapple, apples, peppers, eggplant, mangos, guavas, avocados and lemons.

That shouldn’t be a surprise to many, as Miami rests at the heel of the Florida peninsula and is surrounded by Biscayne Bay on one side and the Everglades on the other, offering bountiful soil and access to many products. But before we get into that, let’s take a trip through time and take a peek at the life of the first inhabitants of the area, the Tequesta Indians, who settled at the mouth of the Miami River where it meets Biscayne Bay. What remains of their past is preserved at the location of present-day Miami Circle in the heart of downtown Miami. The history books detail what these first settlers enjoyed (while some of these delicacies exist today, others have disappeared in use and popularity through the passage of time): saw palmetto, berries, cocoplums, gopher apples, pigeon plums, sea grapes, palm nuts, prickly pear fruit, cabbage palm, hog plum, turtle meat and turtle eggs, deer, terrapin, a variety of fish, lobster, trunkfish, snails, whale, venison, squirrel and turkey. They also ate clams, oysters and conchs, but shellfish was a minor part of the diet. The sea cow (manatee) and the Caribbean monk seal were delicacies and reserved for the important leaders of the tribe. All this dramatically changes after civilization moves in.

W.C. Smith on his pineapple plantation. Courtesy of the State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory Project.

Seminole Indians harpooned manatees for food. Courtesy of the State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory Project.

One cannot talk about Miami food without tackling the topic of the ingredients. What’s native? What’s nonnative? What’s the difference? The orange is eponymous to Florida, so it’s native, right? I’ll admit that I was confused at first, too. As Raymond A. Sokolov notes:

Before the Columbian Exchange, there were no oranges in Florida, no bananas in Ecuador, no paprika in Hungary, no tomatoes in Italy, no potatoes in Ireland, no coffee in Colombia, no pineapples in Hawaii, no rubber trees in Africa, no cattle in Texas, no donkeys in Mexico, no chili peppers in Thailand or India, and no chocolate in Switzerland.10

In order to fully understand the study and/or history of food, one must define what types of foods these ancient people feasted on in detail. One must also define the types of products that were already available and/or native and differentiate them from the types of products that were brought over and naturalized. What makes a plant native anyway? There is much confusion and debate as to what is truly from the area and what is not. There is a lot of wrong information in books, many of which simply use the incorrect wording. There are many books that detail what grows best in a certain region, but most fail to detail the origin of these foods, and just because it can be grown in a region does not mean that it is indigenous to a said region. A lot of the food products that are native to the area are things that we would not use nowadays. In a Tequesta article from 1942 titled “Food Plants of the DeSoto Expedition,” the first example of what is considered the original American diet from 1500 is detailed: Chicasaw plums; wild sweet potato; sunflower seeds; acorns; Jerusalem artichoke; persimmons; plums; honey locust seed pods; chestnuts, which they would use for oil and bread; hickory nuts; corn; calabash gourds; mulberries; strawberries; blackberries; sassafras; young onions; pumpkins; beans; yaupon; wild peppers; and coontie.

“Miami is located in what is considered the lowland humid tropics. This means a lot of different things. This area is rich in productive starchy perennial staples. Crops like bananas, breadfruit, sago palm, peach palm, air potato, and Tahitian chestnut are very high yielding. The region is also well supplied with perennial oilseeds like oil palms, Brazil nuts, and avocados. In the study of plants in pre-Columbian times, it has been shown that what was going on in Florida varied greatly from that of other southern states. Florida sites lacked many of the starchy plants and contained different species of nuts as compared to more northern locations.”11

There are over fifty edible plants native to the area, including American licorice; American persimmon; clovers; California walnut; Dillen’s prickly pear; cow parsnip; Lisban yam; Darling plum; gopher apple; ground nut; pigeon pea; pond apple; sea grape; saw palmetto; tabasco pepper; yerba buena; red maple, which is used in the production of maple syrup; cocoplum; Seminole pumpkin; strangler fig; Indian fig; pokeberry; cabbage palm; and the muscadine grape. In the early days of Florida, the most important plants were the guava, cabbage palmetto, pineapple, yucca, lime, sapodilla, coontie and the Seminole pumpkin. Fish and other seafood native to the area included alligator, blue crab, clams, flounder, grouper, king mackerel, mahi-mahi, mullet, mullet roe, oysters, pompano, red and yellowtail snapper, shrimp, Spanish mackerel, spiny lobster, stone-crab claws, swordfish, tilapia, tilefish and yellowfin tuna. Slow Food International is an organization on a mission to preserve food traditions and food products. A variety of local products that are in danger of extinction include the Wilson Popenoe avocado, American persimmon, Hatcher mango, Pantin mamey sapote, Florida Cracker cattle, Gallberry honey, traditional sourghum syrup, sea grape, Royal Red shrimp and the Hua Moa banana. All of the products are part of Slow Food International’s Ark Food preservation project.

Regardless of whether or not a product is native or nonnative, what can be grown in the greater Miami area? All of the aforementioned native crops can be grown, along with the following: bananas; blackberries; blueberries; cantaloupes; coconuts; papayas; pomegranates; basil; chives; cilantro; cumin; oregano; parsley; rosemary; sage; thyme; mint; corn; hearts of palm; shallots; pecans; white mushrooms; peppers (green, red, yellow, orange, habanero, banana, finger hot, jalapeno, red chili, sweet, hot); mamey sapote; lychee; passion fruit; tangerines; tamarind; guarapo; saoco; ugli fruit; calamondin; mirliton (chayote); atemoya; black sapote; canistel; jackfruit; loquat; jaboticaba; longan; monstera deliciosa; muntingia calabura; white sapote; sugar apple; annatto (achiote); boniato; dasheen (taro); malanga; yam; plantains; snap beans; pole beans; lima beans; beets; broccoli; cabbage; cantaloupe; carrots; cauliflower; celery; Chinese cabbage; collards; sweet corn; cucumbers; eggplant; endive-escarole; kohlrabi; lettuce (crisp, butterhead, leaf, romaine); mustard; okra; onions (bulbing, green); peas; Southern peas; potatoes; sweet potatoes; radishes; spinach; summer spinach; squash (summer, winter); strawberries; turnips; watermelons (large seedless, small); Brussels sprouts; cassava; dandelion; dasheen; dill; fennel; garbanzo beans; garlic; kale; leek; luffa gourds; honeydew melons; rutabagas; blood oranges; pomelos; sour oranges; tangelos; carambola (starfruit); dragon fruit; kumquats; Tahitian and Persian limes; wax jambu; and peanuts.

The following is a list of the fish and other seafood that can be caught in Miami’s waters: amberjack; catfish; dolphin; grouper; Florida pompano; flounder; mullet; mangrove snapper; red snapper; bay scallops; blue crab; clams; conch; Florida spiny lobster; mussels; oysters; shrimp (pink, brown, white, rock, stone); five types of tuna; wahoo; cobia; and kingfish.

As the Florida Food Guide notes:

The first inhabitants of Florida included various tribes of Native Americans who were hunters and fishermen. These indigenous people relied on Florida’s wildlife as their major source of food. The Florida natives hunted bison, deer, and other animals and foraged for wild nuts and berries. With the arrival of Ponce de Leon from Spain in 1513, the multicultural infusion of Florida’s food began, signaling a drastic change in diet for Florida natives. As more European explorers came to Florida, the state’s culinary styles became extremely diverse. Not long after the Spanish began to settle in Florida, more immigrants began to arrive, including the Africans who were brought to America as slaves during the 16th century. The foods and dishes of the Native Americans, Spanish, and other Europeans were greatly influenced by the ingredients, spices, and methods of food preparation that the Africans brought from their home country. White Americans who migrated south to settle in Florida also played a major role in flavoring the taste of Florida’s regional cuisine. They found various ways to use Florida’s indigenous ingredients like guavas, fresh seafood, wild ginger, and many more local foods. As time progressed, the basic Spanish and Southern cuisine of Florida blended with that of a number of other cultures.12

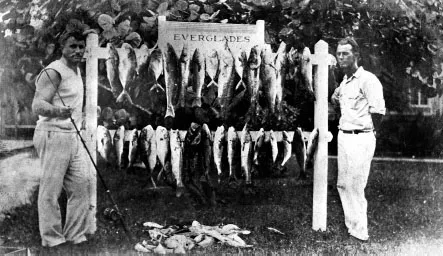

A day’s catch of fish in the Everglades. Courtesy of the State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory Project.

Christopher Columbus played a crucial role in the transference of food information, as his arrival set in motion a trail of very important events, including European diseases that wiped out millions of indigenous people, invaded with armies, killed armies of people and uprooted cultures. Columbus introduced Old World crops to the New World and vice versa. Sokolov writes:

Everyone speaks an idiolect—his own personal language that functions within the larger speech community. A full-blown dialect is a set of idiolects so similar they form a recognizable minilanguage: the Spanglish of United States Chicanos, the nasal twang of the Great Lakes, Valley Girl talk in California. The same thing happens in the kitchen. Every family has its own set of recipes and eating habits, its idiocuisine formed by foods being passed down from the previous generation and through contacts with new foods, flavors, and tastes. And if the similar experiences of many neighboring families evolve into a new “dialect” of eating and cooking—because these families have all changed their idiocuisines after galvanizing contact with new conditions, ingredients, and food ideas—then the world has a new regional cuisine.

Cuisines evolve almost instantly when two cultures and their ingredients meet in the kitchen, and old cuisines never die; they add new dishes and ingredients to old recipes and slough off the losers, the evolutionary dead ends. The net quantity of culinary diversity probably remains the same, and of course we now take cooking seriously enough to write down recipes for the dishes that are in danger of disappearing.

This process of constant evolution in the world’s kitchens went into high gear 500 years ago when Columbus landed in the West Indies. By 1600, Europe and the Americas had exchanged the fundamental ingredients and ideas of their cuisines.13

Gary Ross Morimo adds:

Like sugarcane, the orange made a journey to the New World that was long and legendary. First mentioned in the Five Classics of Confucian China, the orange migrated from Asia to Malaysia, and then to India, Persia, Africa, Sicily, and southern Spain. In the garden of earthly delights, the orange held an honored spot. Columbus introduced citrus to the star-crossed Spanish colony at La Navidad, and Dominicans and conquistadors carried seeds across the Straits of Florida. A dazzling variety of oranges took root in Florida. 14

Today, the study and preservation of our native products are kept alive in the research centers of The Kampong, Fruit and Spice Park and the Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden. Additionally, The Kampong was the historic site of the Jelly Factory, owned by Captain Albion Simmons, who planted guavas and made jelly and wine from them. This eventually became the home of David Fairchild, who had the task of introducing many tropical plants (approximately thirty thousand) in the area and the rest of the United States.

SASSAFRAS JELLY

Ingredients:

6 roots of red sassafras

3 cups water

1 bottle of liquid pectin

3 cups wild honey

*3 tbsp sassafras powder

Preparation:

Wash the red sassafras roots and boil in the 3 cups of water until water is reduced to 2 cups. Strain liquid into another pot an add one bottle of liquid pectin (used for making jellies.) Bring to simmer. Add the honey and sassafras powder*. Simmer 10 minutes. Pour into clean, hot preserve jars. Cover, cool...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1. The Ingredients

- 2. Why Miami?

- 3. Pre-Columbian South Florida—Early Miami

- 4. 1920s–1940s

- 5. 1950s–1970s

- 6. 1980s and Beyond

- 7. Dairies, Supermarkets, Fast-food Restaurants and a Bakery

- 8. Recipes and Other Finds

- Conclusion

- Endnotes

- Bibliography

- About the Author