eBook - ePub

The Civil War on Hatteras

The Chicamacomico Affair and the Capture of the U.S. Gunboat Fanny

- 147 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Civil War on Hatteras

The Chicamacomico Affair and the Capture of the U.S. Gunboat Fanny

About this book

A noted Civil War historian chronicles the fascinating role played by North Carolina's Hatteras Island in the War Between the States.

Hatteras Island was home to many Civil War firsts—among them the first Confederate capture of an armed Union vessel and the first combined amphibious assault of the Confederate army and navy. With illuminating research and vivid prose, historian Lee Oxford demonstrates why these episodes make Hatteras Island vital to the story of the Civil War.

The Confederates' desire to regain control of this Outer Banks island saw the capture of the U.S. gunboat "Fanny." This in turn led to the famous Chicamacomico Affair at Live Oak encampment. The skirmish featured harrowing acts of valor by the Twentieth Indiana Regiment, as well as a path toward victory for the Confederate forces.

Hatteras Island was home to many Civil War firsts—among them the first Confederate capture of an armed Union vessel and the first combined amphibious assault of the Confederate army and navy. With illuminating research and vivid prose, historian Lee Oxford demonstrates why these episodes make Hatteras Island vital to the story of the Civil War.

The Confederates' desire to regain control of this Outer Banks island saw the capture of the U.S. gunboat "Fanny." This in turn led to the famous Chicamacomico Affair at Live Oak encampment. The skirmish featured harrowing acts of valor by the Twentieth Indiana Regiment, as well as a path toward victory for the Confederate forces.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Civil War on Hatteras by Lee Thomas Oxford in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

“Every Case Is a Tragic Poem…A Pensive and Absorbing Book If Only It Were Written”

Every one of these cots has its history—every case is a tragic poem, an epic, a romance, a pensive and absorbing book, if it were only written,” wrote Walt Whitman, essayist, poet and volunteer nurse, reflecting on the Union soldiers suffering in makeshift hospitals in and around the nation’s capital during the second year of the rebellion.12 One of the best of those provisional hospitals Whitman visited was the Indiana Hospital, originally established in September 1861 to care for the “sick soldiers at Washington City belonging to Indiana reg’ts.”13

Confined to two wings of Washington’s Patent Office Building, the Indiana Hospital was also widely known as “the Patent Office Hospital.” The edifice Whitman appreciated as “that noblest of Washington buildings”14 was modeled by architect Robert Mills after the Parthenon of Athens. Situated on an entire city block between Seventh and Ninth Streets, and F and G Streets, the Patent Office rose halfway between the scaffolding of the unfinished Capitol dome to the east and the president’s house down Pennsylvania Avenue to the west. The Patent Office was a ten-block walk, just over a mile, from the Baltimore & Ohio (B&O) Railroad depot and the nearby Soldiers’ Rest, where Union soldiers were quartered and fed a warm meal while waiting to be carried south, sent to the rear, reassigned to skeleton regiments or discharged and sent home.

Private John Henry Andrews, recently of Rossville, Illinois, and a musician from the Twentieth Indiana Regiment’s Company H, made the thirty-minute trip from the Soldiers’ Rest to the Indiana Hospital just a few days following his arrival in Washington from the heart of the Confederacy. Andrews accompanied his company comrade Private Elias Oxford who suffered with advanced symptoms of typhoid fever and had orders from the Sanitary Commission for immediate admission to the hospital.15

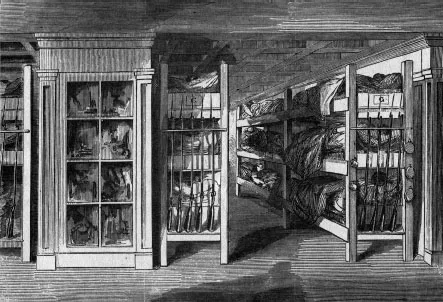

Model room located inside the Old Patent Office Building in Washington, D.C. In 1861 and 1862, this room was used as part of the Patent Office Hospital, also known as the “Indiana Hospital.” Library of Congress.

Union soldiers’ bunks in Patent Office, 1861. Harper’s Weekly.

Private Andrews and his Hoosier friend were among hundreds of Union POWs recently removed from Richmond’s Libby tobacco warehouse prison at daybreak on Monday, May 12.16 That same morning, in the North, the New York Herald ran a headline announcing, “Norfolk Is Ours!” Norfolk and Gosport Navy Yard had fallen into the hands of the Federal government on the evening of May 10 after a combined operation of the Union army and navy, an operation designed by President Lincoln himself. Federal war vessels had begun looking farther up the James River, then, putting additional and intense pressure on Richmond. The Confederates wanted to rid themselves of prisoners, particularly the sick, considered a draw on resources and excess baggage in the event of a full Rebel retreat from Richmond.

Some 885 paroled prisoners of war boarded two Rebel flag-of-truce steamers, the Curtis Peck and the Northampton, which stood waiting along the James River at Richmond. Several dozen of the parolees signed in advance on May 1, including those of Andrews and Oxford, were for Twentieth Indiana men, along with eleven Hawkins Zouaves, all who had been captured on Hatteras Island in two engagements the previous October.17

Steaming down the James from Rocketts Landing, past Drewry’s Bluff in the early light of dawn, the ships carrying the released prisoners hove within sight of the USS Port Royal by 6:30 a.m.18 and soon thereafter in view of the Union ironclads Galena and Aroostook just below Jamestown. Twenty or more miles up from Newport News, Virginia, nearing Hardy’s Bluff, the soldiers caught a good look at the Federal ironclads Naugatuck and Monitor and stood in disbelief as the Monitor refused a reply to the Rebel batteries of Fort Huger, which opened up on it from the bluff: “The prisoners gave her three cheers; and in response to a question, asking why he did not silence the batteries, the officer commanding replied that they had more important work to do up river.” At Newport News the paroled Union prisoners first heard of the Confederate evacuation of Norfolk and the Navy Yard and of the scuttling of the CSS Virginia, which the men were still calling by its former Federal name, Merrimack.19 The prisoners recalled having passed the Merrimack at Gosport Navy Yard upon their departure from Norfolk Jail to Richmond by train the previous October, more than two-hundred days earlier.

The parolees headed up the Potomac from Fort Monroe for Washington on May 14,20 arriving in the evening at their temporary quarters, a “long low building constructed for the use of soldiers” at the Soldiers’ Rest near the B&O station.21 Having taken an oath not to take up arms against the Confederacy again in exchange for their freedom, the men readied to be paid and mustered out.22

The May 14 homecoming to the nation’s capital splendidly punctuated Private John Andrews’s twenty-fifth birthday. Private Oxford, though, was in failing condition on arrival. He had experienced symptoms similar to influenza earlier, prior to release from Libby Prison. Food and water in the Southern prisons during the war were often contaminated by raw sewage through various means, which apparently happened at Libby within a couple weeks of Oxford’s release. Typhoid’s early stage fever and rash gave way day by day to blurred vision, increased diarrhea, a tender distended abdomen and finally “muttering delirium.” Death was just a step away. By the time the Sanitary Commission wrote its orders, it was too late for the primitive medicines to have any curative effect. On Sunday, May 18, Private Andrews brought Oxford to the Patent Office in what the surgeon described as “a morbid state.” Oxford’s illness was so advanced that he was unable to give his age, place of birth, marital status or residence. Andrews later provided some minimal information, noting he thought Oxford was married and that his next of kin resided in Iroquois County, Illinois.23

Private John Henry Andrews was already intimately acquainted with the atmosphere of death and the contagious diseases that hasten its coming. Both of Andrews’s parents died in the summer of 1847 at the immigration depot and quarantine station of Grosse Isle, in Gulf of St. Lawrence in Quebec. Andrews’s family was English, and his father, Vincent, was a sergeant in Her Majesty’s Coldstream Regiment of Foot Guards. The Second Battalion Coldstream Guards were sent to Lower Canada (Quebec) in 1838 to support troops there in the suppression of the rebellion, or Patriots’ War, stirred up at the end of 1837 by radical French-Canadian leaders, such as Louis-Joseph Papineau. It seems Sergeant Vincent Andrews and family arrived in the British colony late in 1839, two years after John’s birth in Southwark, Surrey. John’s younger sister was born in September 1839 onboard the ship between Portsmouth and the Canadas. The Second Coldstream left Canada in 1842, however, and returned to England. The Andrews family stayed in the colony, though, moving to Grosse Isle, where Vincent served as a nurse, or “surgeryman,” fighting the 1847 typhus pandemic, with ship after ship arriving daily, filled with dead and dying Irish immigrants. By July 1847, typhus claimed Vincent and his wife, Mary Ann, and orphaned John, at the age of ten, along with a younger sister and brother. Such was Private Andrews’s early education in death and disease, which cultivated in him a lifelong sensitivity and nurturing spirit toward the sick and dying.24

Andrews and Oxford—both of the Twentieth Indiana Regiment’s Company H, and both captured on the U.S. gunboat Fanny—had stuck it out together throughout their nearly ten months in service to the Union cause. All but two months of that service since their capture at Hatteras was spent in the Rebel prisons of Norfolk, then Richmond and Columbia, South Carolina. By late February, the POWs were back in Richmond and, in March, were among the first to walk through the doors of the newly opened, and later notorious Libby Prison. Private Andrews had spent every day of those nearly eight months in confinement together with his comrade and now sat devotedly with Oxford in those final hours of his life, which was fading within the marble-tiled halls of the Patent Office. Andrews doubtless found the medical facilities in the North and West Halls of the Patent Office much the way Walt Whitman did, as a

strange, solemn, and, with all its features of suffering and death, a sort of fascinating sight…filled with high and ponderous glass cases crowded with models in miniature of every kind of utensil, machine, or invention it ever entered into the mind of man to conceive, and with curiosities and foreign presents. Between these cases were lateral openings, perhaps eight feet wide, and quite deep, and in these were placed many of the sick; besides a great long double row of them up and down through the middle of the hall…Then there was a gallery running above the hall, in which there were beds also. It was, indeed, a curious scene at night when lit up. The glass cases, the beds, the sick, the gallery above and the marble pavement under foot; the suffering, and the fortitude to bear it in the various degrees; occasionally, from some, the groan that could not be repressed; sometimes a poor fellow dying, with emaciated face and glassy eyes, the nurse by his side, the doctor also there, but no friend, no relative—such were the sights but lately in the Patent office.25

The miniatures on display in glass cases throughout the halls of the hospital were a most curious assortment of machines, tools, instruments and contraptions, mostly made after the 1836 Patent Office fire, which destroyed the original Patent Office, its records and models. The United States government, in the nineteenth century, required applicants for patents to submit a made-from-scratch model, no larger than twelve-inches square, along with a detailed drawing of the specifications of the machine. The result was thousands of these handcrafted models housed in tall glass cases lining the corridors. Included were Samuel F.B. Morse’s telegraph register of 1849, along with cook stoves and nautical instruments, mousetraps and steam engines, propellers and tobacco cutting machines. Each model was a means for Private Andrews to “visually turn back time.” Each could conjure visions of things and events that had broken into his world since the previous summer. The joy of wearing fresh and new Union blue had been snatched away at Hatteras Banks aboard the propeller steamer Fanny off Chicamacomico and then on the lonely overcrowded floors of Liggon’s and Libby’s tobacco warehouse prisons of Richmond and the cramped county jail of Columbia, South Carolina. Private Andrews, as he sat beside his dying comrade in those last hours, had time to reflect on how truly and wonderfully strange it was just to be home again on his adopted Union soil.26

Chapter Two

“I’m But a Stranger Here”

The Twentieth Indiana Volunteer Infantry Regiment arrived at Fort Monroe the morning of September 25 and immediately pitched tents on “a field of frost.” The regiment camped only one night at the fort, though, before receiving orders for Hatteras. There was no time to investigate Hampton or the fort itself.27 The Twentieth broke camp the next morning and was steaming south to Hatteras Inlet by nightfall.

The men of the Twentieth, though, were not walking as tall as they might. Commander of the Department of Virginia, Major General John E. Wool noted on their arrival at Fort Monroe from Baltimore that the regiment was “badly armed” with old altered muskets, about 150 of which were actually unfit for service.28

Raised as a “rifle regiment,” the Twentieth Indiana discovered in Indianapolis in July that all but two companies would receive outdated Harpers Ferry smoothbore muskets. At the outbreak of the war, there were simply not enough new Springfield rifles to supply so many troops. The Twentieth instead was issued the old 1795-design Springfield flintlocks altered to use percussion caps in 1842 at the Harpers Ferry Armory. Each altered musket fired a single cartridge containing one .69 caliber ball and three buckshot each.29

Only two Twentieth Indiana companies received Springfield Model 1855 rifles in the initial issue. These were Captain John Van Valkenburg’s Company A and Captain John Wheeler’s Company B, the right and left flanks of the regiment.30 The Springfields were consistently accurate in battle at up to three-hundred yards with a .58 caliber Minié ball and, in the hands of a skilled sharpshooter, could be accurate up to one thousand yards.31 One of the Twentieth’s two rifle companies were favored the night of August 6 with the thrill of firing off a few shots at secessionists attempting to set fire to the Northern Central Railroad bridge spanning the Gunpowder River north of Cockeysville, Maryland.32

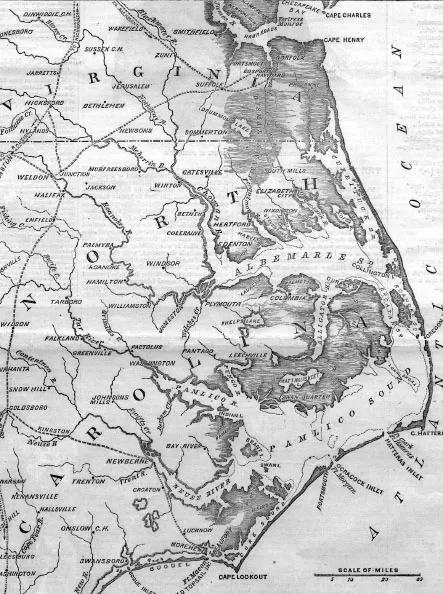

“Map of North Carolina, Showing Fort Hatteras and the Sounds It Commands.” Outer Banks History Center.

Wool ordered the Twentieth’s “unfit” Harpers Ferry muskets traded in for old Confederate muskets, which had been surrendered by the Seventh North Carolina troops at Fort Hatteras on August 29.33 This was not a significant improvement but certainly is an indication of the wretched condition of the original smoothbores. Wool held the regiment’s departure until it was also adequately supplied with...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword, by Dennis C. Schurr

- Foreword, by R. Drew Pullen

- Preface

- Introduction: “These and Similar Trophies”

- 1. “Every Case Is a Tragic Poem…A Pensive and Absorbing Book If Only It Were Written”

- 2. “I’m But a Stranger Here”

- 3. “To-night I Shall Start for Chicamacomico”

- 4. “We Feel As If We Stand upon Our Native Soil of the Union”

- 5. “In Honey and Clover up to Their Eyes”

- 6. “A More Hair-brained Expedition Was Never Conceived”

- 7. “What Madness Rules the Hour!”

- 8. “Over a Thousand New Blue Winter Overcoats”

- 9. “The Command Will Remain and See What Will Turn Up”

- 10. “Stern and Savage War Was Upon Us”

- 11. “I Expected Every Minute to Be Blown to Atoms”

- 12. “The Most Remarkable Naval Report of the War”

- 13. “Volunteer Navy Lieutenant Francis M. Peacock, Commanding the Fanny”

- Epilogue

- Appendix A: Locating Camp Live Oak at Chicamacomico (Rodanthe), North Carolina

- Appendix B: Union Prisoners Captured Aboard the U.S. Gunboat Fanny

- Appendix C: Union Prisoners Captured During the Chicamacomico Affair

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Author