![]()

Chapter 1

SACRAMENTAL GOLD

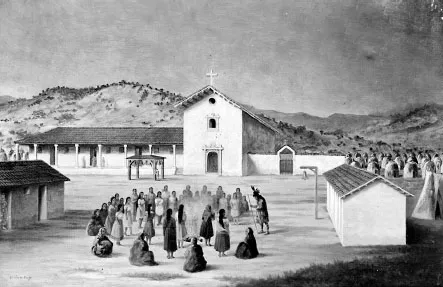

California’s wine history began with the Franciscan missionaries, who were sent by Spain in the mid- to late eighteenth century with a purpose of spreading Christian faith to the native people. As they established missions along the Camino Real, or Royal Trail, from San Diego to Sonoma, they planted Mexican grapes for sacramental use and trade. These black grapes were called criolla but became known as “missionary grapes” and were California’s first real grapes planted for wine.

Franciscan fathers like Friar Jose Altimira, who founded the Mission San Francisco de Solano, spread Christianity to the natives while they busily engaged in trades. Solano was founded on July 4, 1823, and was the twenty-first mission in California. The natives, mostly not there by choice, tilled the land and planted numerous orchards and vineyards. Many lonely pioneers visited their missions, as they often functioned as hotels since there were none at the time. Pioneer Vincent Carosso visited the missions often and wrote of the Sonoma Mission, “[I] was very kindly received by the Padre, and drank as fine red California wine as I ever have since, manufactured at the Mission from grapes brought from the Mission of Santa Clara and San Jose.”

Until the mid-1800s, the mission grape was the primary winemaking grape in California. As time progressed, mission grapes were used for brandy, table wine and Angelica, which was a fortified wine. Nineteenth-century historian Hubert Bancroft noted that the sweet, reddish-black mission grape in Los Angeles was referred to as the South Spanish stock. He also noted that the black Sonoma was fruitier and yielded a lighter wine. While the mission grapes served as the sacramental wine for the missionaries, a completely different version of California wine would debut some fifty years later.

Sonoma Mission, circa 1835. Mission San Francisco Solano was founded on July 4, 1823 (twenty-first in order), by Padre Jose Altimira. The mission is named for St. Francis Solano, missionary to the Peruvian Indians. The Indian name was thought to be Sonoma. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Ludwig Louis Salvator was the archduke of Austria and visited the area in the 1870s, writing this about mission grapes:

Among all the products of Los Angeles none, probably, is more important than the grape. The so-called mission grape was brought in by the fathers in 1770 and extensively raised by the Indians under this tutelage. This, presumably, was of the Malaga variety known as Vino Carlo. In Mexico, however, from where the first cuttings were imported, many of its salient characteristics were lost, and it no longer resembles the Malaga grape. Though only a fair wine can be made from it, the fathers gave it the preference since it was both hardy and a prolific bearer. Even now 75 per cent of the grapevines in California are hardy bearers. In shape it is perfectly round, being when fully developed about three-quarters of an inch in diameter. While ripening it is of a reddish-brown color; when fully ripe it is a beautiful black and full of sweet juice, but without aroma. This is a considerable detriment, not only in the preparation of wine, but also in its use as a table grape. Wine made from this sort of grape is quite strong, resembling Port and Sherry. In and about Los Angeles the mission grape is especially popular and it was not until 1853 that new varieties of grape, especially those from Europe, were imported. These have gradually taken the place of the old mission grape, such kinds as the Flaming Tokay, Rose of Peru, Black Morocco, Black Hamburg, and the White Muscat being highly favored.

Mission grapes were also planted at Sutter’s Fort before the great gold rush took place. Native New Yorker John Bidwell sought his fortune in California in 1841 and journeyed west as part of the first migrant train going overland from Missouri to California. He found work at Fort Sutter and sided with Governor Micheltorena in the 1844 revolt, but he aided the Bear Flag rebels in 1846. After serving with John Fremont, he returned to Fort Sutter. Bidwell was among the first to find gold on Feather River and used his earnings to secure a grant north of Sacramento in 1849. He spent the rest of his life as a farmer at “Rancho Chico” and became a leader of the state’s agricultural interests. He claimed that

California is emphatically the land of the vine; and can there be any doubt that we can produce the finest wines? This is an important question, because we are actually importing in casks, barrels, baskets and cases, millions of gallons every year. And yet it is admitted that there is not a land beneath the sun better suited to grape culture than California. The name of Los Angeles is as famous for wine and for the grape as that of California for gold. But the grape flourishes well everywhere, and its cultivation is being extended all over the State.

Pioneer Heinrich Lienhard recalled his first trip to gold rush country:

On the seventh of January, 1848, Sutter and I rode out on horseback to inspect the property he had selected. It was situated in a country where the summers are unusually dry, near a broad, deep slough that was separated from the mouth of the American Fork by a kind of island, and proved to be an excellent site for a garden. When the tide was high, the American River over-flowed into this slough, which was deep enough to hold an ample supply of water for our garden during the dry months…For two or three weeks Sutter had been acting queerly. One day I had some business to transact in the fort; since it was noon I stayed there for dinner, and as I was leaving, he brought out a dirty old rag in which something was tied. He unfastened the knot, and showed us eighteen or twenty small pieces of metal, the largest about the size of a pinhead. These small grains were yellow and we began to think they might be gold.

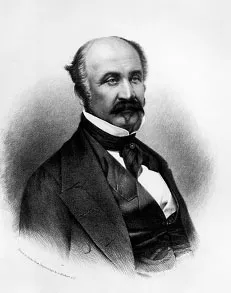

The man who discovered the gold was an employee of General John A. Sutter named James W. Marshall. New Jersey native Marshall was working in Coloma for Sutter when he suddenly appeared at Sutter’s home with a small item wrapped in a cloth. His secretive manner caused Sutter some concern, but Sutter abided by Marshall’s wishes and met behind closed doors in Sutter’s home. What Sutter saw would change California’s history forever. Gold was discovered in 1848, and it lasted for four short years, with the last two seeing the supply dwindle to nothing more than dust.

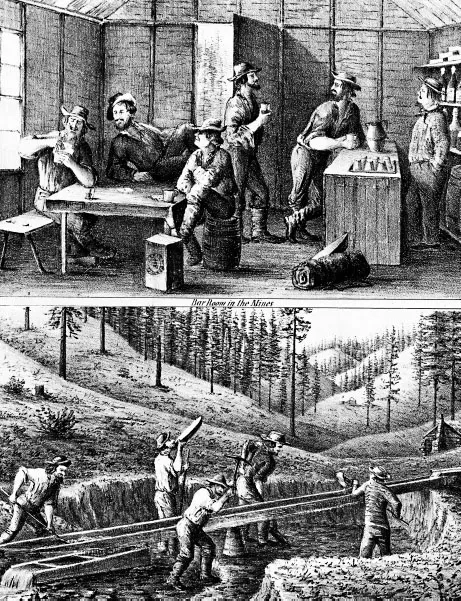

That year, 100,000 miners earned an average $600 per year, despite wages for common labor being two to three times higher. The gold rush ended almost as quickly as it began, which left thousands of immigrants within a few years with no fortune and no job. A portion of them followed the next big mining circuit in America, which at the time was in Colorado, and some sailed back to their native countries; others still stayed and found employment. With California’s burgeoning population, many found new occupations, including farming, grape growing and winemaking, which they had known in their own countries.

Major John August Sutter, 1859. Sutter wrote, “It was in the first part of January, 1848, when the gold was discovered at Coloma, where I was then building a sawmill. The contractor and builder of this mill was James W. Marshall, from New Jersey.” Courtesy of Library of Congress.

J.G. Player-Frowd was an Englishman who visited California in the early 1870s and observed, “The early wines of California were all falsified being mixed with strong foreign wines. The Los Angeles wine was not good enough to send out in its natural state, so the dealers doctored it, and these compounds went by the name of California wine, bringing no credit to the country. Meanwhile it was found that the mining towns in the mountains grew better grapes than the old Missions, and that the valleys of the coast range made better wine than any.” He considered the “four great wine-growing districts” to be “Sonoma Valley, Napa Valley, Los Angeles, and Eldorado.”

Barroom in the mines, circa 1850. Once news of the gold discovery was out, people descended on the area near Sutter’s Fort. Basic staples, including wine, were far from cheap. According to gold rush pioneer Jacques Antoine Moerenhout, a bottle of “ordinary wine” or brandy sold for eight dollars, and the price of placer gold was paying sixteen dollars per ounce. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

![]()

Chapter 2

NAPA PIONEERS

North Carolina native George C. Yount was the first white pioneer to arrive in the area by 1831, and in 1836, General Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo granted him the 11,814-acre Caymus Rancho. Two years later, he planted the first vines in Napa. A few years later, Rancho La Jota was also granted to Yount, and he surveyed the town of Yountville, which was named after him.

Today, Napa Valley is home to numerous outstanding wineries and vineyards, but before pioneers like Yount moved to the area, it was home to the Caymus Indians and numerous grizzly bears, which were known to frequent the area. Frank Leach was an early pioneer and newspaperman who recalled of Napa in the early days, “Napa Valley was early recognized as a section favorable for the growing of fruit, and a few enterprising farmers gave their attention to that business. Wells and Ralph Kilburn were among the pioneers. A man named Osborne planted the Zinfandel Oak Knoll orchard, and Captain Thompson the Suscol orchard, both of which became famous throughout the state before 1860. As is generally known, Napa in later years became noted as the largest wine growing district in the state.”

He continued:

Orchards and wheat fields disappeared, being replaced by vineyards which for a time gave great profit to the owners, which probably was the cause of the overdoing of the business, placing the producers at the mercy of speculators…The first vineyard for wine making purposes was planted in the latter part of the ’50s by John Patchett on a piece of land about a mile north-westerly from the courthouse in the town of Napa. Here the first wine on any scale was made. Doctor Crane, a physician in Napa, a very intelligent and observing man, had become thoroughly impressed with the idea that the soils and climate of Napa Valley were particularly favorable to the culture of the grape for wine purposes. As early as 1857, he contributed column after column to the pages of the local paper, giving his reasons therefor and urging the planting of vineyards, calling attention to the possibilities of the poorer lands, useless for the growing of grain. The doctor kept up his publications for two or three years, or it may be longer, until he finally gave up his practice and bought a brushy and gravel covered piece of land near the town of St. Helena not considered worth fencing and planted the vineyard that subsequently became famous.

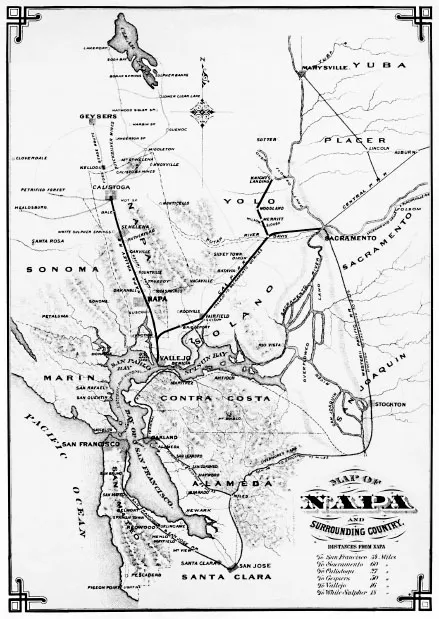

Napa area map, circa late 1800s. L. Vernon Briggs visited Napa in 1881 and recalled, “To the visitor at Napa City today, the statement that a little more than thirty years ago the site of the now lively little city was a ‘howling wilderness’ sounds more like a fable than a reality; and yet such is the case. It is situated in the midst of a country noted for its mild and genial climate, the great fertility of its soil, and its many well-cultivated vineyards. Those in Napa Valley produced in one year over twenty-six hundred thousand gallons of wine and brandy. This production was from sixty-one cellars.” Courtesy of Charles Krug Winery.

While Yount both established a community and was a viticulturist, David Fulton was an inventor who focused on wine. After nearly two years of making saddles, horse-drawn carts and cast-iron parts, Fulton established his own vineyard by purchasing a forty-acre parcel of land from Frank Stratton on January 12, 1860. In the spring of that year, he planted about six acres of grapevines. The next year, anticipating more mature harvests to come, he sold fifteen of his undeveloped acres to finance his forty-eight- by twenty-eight-foot stone wine cellar. Fulton hired Anton Rossi of Spring Valley, and together they hauled one thousand square yards of dirt and moved in one hundred square yards of rhyolite rock quarried from the valley’s eastern hillsides to build the cellar walls. Rossi was a native of Switzerland and arrived in America in 1871. By 1901, he had established his own winery.

The winery itself was a board-and-batten structure made of redwood planks milled from trees taken in the western hillsides. By May 1865, he was making and selling brandy. On August 7, 1869, Fulton was appointed to a committee of seven vintners at a California Agriculture Convention. Fulton was also a businessman, benefactor, trustee, inventor and town visionary. In 1870, utilizing skills as a blacksmith and the knowledge gained as owner of the town saddler, he invented the Fulton plow. David Fulton died in the fall of 1871, just two weeks before the grape harvest. The operation was left in the hands of David’s wife, Mary Albino (Lyon) Fulton. In January 1876, she hired winemaker William Scheffler to take the helm. Mr. Scheffler worked for a year and a half retooling the old wine cellar. Scheffler was able to bring production up to current standards by the fall of 1877, doing so with enough momentum to carry the operation into the next decade as the M.A. Fulton Winery. Mary’s health began to fail, and the Fultons decided to abandon commercial winemaking and concentrate solely on the vineyard during the 1880s.

David Fulton, circa mid-1800s. David was one of the first, if not the first, to plant vines in Napa. Today, their vineyards, originally planted in 1860, produce fewer than four hundred cases of Petite Sirah a year from their dry-farmed estate vineyard, which has been continuously family owned and operated. Courtesy of David Fulton Winery.

Mary’s two daughters, Ida and Alice, were given the ranch when Mary died in 1893, and Ida continued to live on the ranch and eventually acquired her sister’s share of the property. Ida married Edgar Washington Mather in 1897, and the two expanded the vineyard acreage, erected a barn and built a tank house that stands today next to the 1864 farmhouse. Around the turn of the century, Edgar and Ida Mather bore three children: twins Edgar and Fulton and Gladys. With Edgar and Ida gone by the start of the 1930s, the property went to their three children. Shortly after, the brothers Edgar and Fulton gave their ownership of the farmhouse and vineyard to their sister. Gladys Mather married Ferdinand Wallace Beard, and the couple had a son named Edgar Darrel Beard and also took in Gladys’s nephew, Fulton I. Mather Jr.

Both Edgar and Fulton worked in the vineyard, and several years later, when Gladys passed away, she gave a small portion of the St. Helena property to her grandson, Ed Beard Jr., while her son received their Yountville properties. The remainder of the St. Helena property went to Fulton I. Mather. Together with his wife, Erma L. Mather, they are current owners of the David Fulton Winery. Today, they produce less than four hundred cases of Petite Sirah a year from their 1860 dry-farmed estate vineyard.

David Fulton’s widow, Mary Albina Lyon Fulton, with her two daughters, Alice (left) and Ida (right), in about 1889. Ida is the daughter who married David Fulton Winery’s current owner’s grandfather, Edgar Washington Mather. Courtesy of David Fulton Winery.

Charles Krug began his winery around the same time as Fulton. He was born in Prussia in 1825, and Krug fought for independence from Germany in 1848. He was even jailed for his activism, yet he was freed nine months later in a second uprising. When the Prussian immigrant arrived in San Francisco in 1852, he had little besides willpower and a willingness to work hard. He became a major local winery figure of ...