- 227 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

One of the nation's most colorful leaders, Confederate general John Hunt Morgan, took his cavalry through enemy-occupied territory in three states in one of the longest offensives of the Civil War. A military operation unlike any other on American soil, Morgan's Raid was characterized by incredible speed, superhuman endurance and innovative tactics.The effort produced the only battles fought north of the Ohio River and reached farther north than any other regular Confederate force. With twenty-five maps and more than forty illustrations, Morgan's Raid historian David L. Mowery takes a new look at this unprecedented event in American history, one historians rank among the world's greatest land-based raids since Elizabethan times.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Morgan's Great Raid by David L Mowery in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

“Knight on a White Horse”

By early June 1863, when Confederate brigadier general John Hunt Morgan first proposed his daring raid into the North, most citizens of the South felt they were winning the American Civil War, even though the tide had already turned against them. For over a year, Union ground forces had been steadily infiltrating and occupying key portions of the fledgling country. They had captured New Orleans, Memphis and Nashville, three of the Confederacy’s largest providers of war materiel. The Union navy’s successful blockade of the Confederacy’s major coastal ports prevented Southern trade for foreign goods, causing the Confederate economy to deteriorate faster. In the political war, President Abraham Lincoln’s signing of the Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863 deterred any notion that Great Britain or France may have had to back the Confederacy and its abhorrent institution of slavery.

The Confederacy’s best attempts to retake its lost territory and bring the war to the Northern states had failed miserably in the autumn of 1862. General Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee, the most powerful force defending the Confederate states west of the Appalachian Mountains, was turned back at the Battle of Perryville, Kentucky, in October. Bragg retreated ingloriously into Tennessee, never again to enter Kentucky with a force of conquering magnitude.

East of the mountains, General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia was defeated in September at the gory Battle of Antietam (Sharpsburg) in Maryland. The Union Army of the Potomac held the field, while the Confederates slipped back into Virginia to fight another day. Nonetheless, Lee’s losses at Antietam were so great that he knew another invasion of the North was out of the question, at least not until he could gather more equipment and men, which the Confederacy had few to provide. Thus, Lee placed his army into a defensive position in northern Virginia, awaiting the onslaught of the Federals’ seemingly overwhelming manpower and limitless supplies.

Northern citizens perceived the battles at Perryville and Antietam to be “indecisive bloodbaths” rather than victories that had turned the tide of the Civil War in their favor. In both campaigns, the Confederate armies had escaped the fatal blows that the war-weary Northern people expected their commanders to deliver. To appease his angry constituency, Lincoln chose to relieve the commanders who had led the Union armies at Perryville and Antietam—Major General Don Carlos Buell and Major General George B. McClellan, respectively. In the late autumn of 1862, the North’s willingness to continue the war effort hung in the balance. In the tip of this scale rested the South’s last real hope to win the war.

Despite his defeat in the Kentucky Campaign, General Bragg remained confident that he could hold Middle and East Tennessee against the Federal juggernaut. Bragg believed Major General William Rosecrans’s Union Army of the Cumberland would not move out of its Nashville fortifications until the springtime. Confederate president Jefferson Davis agreed, so much so that he transferred nearly one-sixth of the Army of Tennessee to Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton to bolster the defenses at Vicksburg, Mississippi, a city that both sides considered vital to winning the war. However, Bragg’s and Davis’s overly optimistic views of the situation in Middle Tennessee quickly dissolved around New Year’s Day 1863, when Rosecrans’s army engaged Bragg’s in a violent three-day struggle among the snow-caked, blood-spattered cedars surrounding Murfreesboro (Stones River). Like Lee, Bragg reacted to this indecisive slaughter by choosing a defensive strategy that would allow him to refurbish his broken army with men and materiel. He retreated southward and formed a line along the headwaters of the Duck River north of Shelbyville and Manchester. Bragg licked his wounds there for the next six months, while Rosecrans, hovering around Murfreesboro, prepared his army for the final fatal thrust.

After the Battle of Stones River, President Abraham Lincoln and the Northern citizenry finally sensed the turn in the war effort. “I can never forget, whilst I remember anything,” Lincoln wrote later to Rosecrans, “you gave us a hard-earned victory, which, had there been a defeat instead, the nation could scarcely have lived over.” The North began to believe that an attack on the hibernating Southern armies could perhaps destroy them, or at the least, it could take away more ground from the Confederacy.

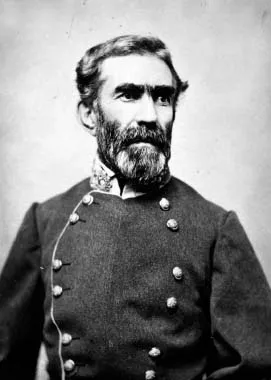

General Braxton Bragg permitted Morgan’s raid into Kentucky but did not authorize its extension into Indiana and Ohio. Bragg later commanded the Confederate army at the Battles of Chickamauga and Chattanooga. He attempted to disband Morgan’s raiders but was thwarted. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

One such offensive began in the early spring of 1863. Union major general Ulysses S. Grant’s Army of the Tennessee made a bold move against Vicksburg, the last major Confederate bastion on the Mississippi River. If Vicksburg fell, the western Confederacy undoubtedly would be split in two, and the Union navy would have complete control of the Mississippi River, a critical avenue of military transport and a natural barrier for enemy ground troops. President Lincoln considered Vicksburg a top target for his western armies.

For the first two years of the war, it seemed General Pemberton’s Army of Mississippi held an impregnable position at Vicksburg that no enemy could take. Grant and his right-hand man, Major General William Tecumseh Sherman, had made four unsuccessful attempts to capture the citadel during the winter of 1862–63 and into the following spring. Their first campaign in December 1862 had ended miserably in the swamps below Chickasaw Bluffs and in the woodlands north of Grenada, Mississippi, at a cost of over 1,700 Federal casualties. A canal construction project and two subsequent water-borne campaigns in the bayous north of Vicksburg also had floundered.

Undaunted by these successive failures, in April 1863, Grant launched a new campaign to capture Vicksburg from the Louisiana shore. Using the armada of Admiral David D. Porter’s U.S. Navy fleet, Grant surprised Pemberton by executing a daring amphibious landing south of the city. Grant’s army immediately followed its success with a brilliant flanking march through Jackson that bottled up the Confederates among the outskirts of Vicksburg. By June 1863, it appeared Grant had the upper hand on Pemberton, and it would only be a matter of time until Vicksburg would capitulate. Even worse, the Army of Mississippi would certainly be lost with it.

During the same time period, two Federal campaigns occurred east of the Appalachians, but they failed to achieve the same successes as those of Rosecrans and Grant. Major General Ambrose Burnside led the Army of the Potomac against Lee in Northern Virginia, but the Union campaign ended in disaster at the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862, and Burnside was relieved of command. The following April, Union major general Joseph Hooker led a refreshed Army of the Potomac across the Rappahannock River, initially catching Robert E. Lee by surprise. However, Lee countered this threat with a brilliant victory at the Battle of Chancellorsville, Virginia, during the first days of May. Hooker’s army retreated northward in dismay, once again thwarted by the smaller Army of Northern Virginia. For his efforts, Lee attained the enduring status of a hero among the people of the South.

The victories at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville, ones that the Confederate nation desperately needed to maintain its morale, also gave Lee the impetus he desired to plan another invasion of the North. Lee and Davis decided the Army of Northern Virginia was ready to take the offensive again. They understood that taking the war to the Union states might sway the Northern people’s attitude toward a quick resolution of the war through recognition of the Confederacy as its own sovereign country. Lee planned to invade Maryland and Pennsylvania through the Shenandoah Valley and, if successful in defeating the Army of the Potomac, perhaps capture Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. He began his offensive, later known as the Gettysburg Campaign, in the middle part of June 1863.

The Confederacy west of the Appalachians still sought a hero like Lee. The nation needed a great victory in the West that would send the bluecoat invaders scurrying back into Kentucky and beyond. The nation searched for a leader who could deliver a knockout blow. Unfortunately, General Braxton Bragg would not prove to be the hero the Confederacy was searching for.

Throughout the first six months of 1863, General Bragg did little to change his war strategy or to fully understand Rosecrans’s plans. Instead, Bragg used the time to reorganize his convalescing army with the thought of eliminating the subordinates he thought were to blame for the defeat at Murfreesboro. The reorganization affected all branches of his army; Bragg selected new leaders he felt he could trust. Unfortunately, he failed to comprehend how badly he had fragmented and demoralized the Army of Tennessee’s command structure.

Bragg also realized that his Army of Tennessee’s position along the Duck River was vulnerable. If Grant was to take Vicksburg and capture Pemberton’s army, Grant could then turn his full attention toward Bragg’s left flank. In addition, another threat loomed farther to the north. Major General Ambrose Burnside, the new commander of the Department of the Ohio, was piecing together a large army in Kentucky that would attack Bragg’s lightly defended right flank under Major General Simon Bolivar Buckner at Cumberland Gap, Tennessee.

Ambrose Everett Burnside was born in 1824 near the hamlet of Liberty, Indiana, situated about forty miles northwest of Cincinnati. An 1847 graduate of West Point, he served in the Mexican-American War and on the American frontier until he resigned from the army in 1853. Returning to civilian life in Rhode Island, he invented the Burnside breech-loading rifle, started an unsuccessful company and worked in the railroad business. At the beginning of the Civil War, he organized the First Rhode Island Infantry and saw action at the First Battle of Manassas, where he earned a brigadier general’s star. He gained national acclaim for his successful amphibious expedition on the North Carolina coast, for which he was promoted in March 1862.

As the leader of the IX Corps at Antietam, and later as commander of the Union Army of the Potomac, Burnside failed to make good impressions on the battlefield. President Lincoln relieved him from command of the Army of the Potomac after the disastrous Fredericksburg Campaign of December 1862. Burnside was reassigned on March 23, 1863, to head the Department of the Ohio, a military zone that encompassed the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, West Virginia and the portion of Kentucky lying east of the Tennessee River. In this “desk job” position, Burnside reorganized the department’s forces into the XXIII Corps, or Army of the Ohio. Burnside did very well in quelling the excessive Copperhead (Peace Democrat) activities in his department, and he prevented wholesale rioting from occurring in his region after the institution of the Federal draft.

Major General Ambrose E. Burnside coordinated all the Federal ground and naval forces that chased Morgan’s raiders. He later commanded Union forces at the Siege of Knoxville and the Battle of the Crater. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

From his headquarters building on Ninth Street between Vine and Walnut Streets in Cincinnati, Burnside planned to fulfill Lincoln’s desire for an invasion of East Tennessee. If Grant and Burnside were to move simultaneously, they could outflank Bragg’s army or, even worse, cut it off from its supply base at Chattanooga, Tennessee. If Bragg could not hold Rosecrans at Tullahoma, Bragg knew he would be forced to fall back toward Chattanooga. In a worst-case scenario, he would establish a new line of defense south of the Tennessee River. By doing so, he would give up Middle Tennessee to the enemy, a loss the Confederacy could ill afford.

In the ensured face-off with his foe, Bragg would rely heavily on his cavalry to screen his army and obtain intelligence about the enemy. He left the chore of accomplishing these tasks to Major General Joseph Wheeler, head of the Army of Tennessee’s cavalry corps. Wheeler had won Bragg’s trust as an obedient subordinate. Although unfit for independent command, Wheeler was a brave cavalry leader with a talent for protecting a large army. Hence, Wheeler served Bragg’s needs. But Bragg’s inability to make the best use of his officers’ talents hamstrung Wheeler’s more independent-minded subordinates, Brigadier General John Hunt Morgan and Brigadier General Nathan Bedford Forrest.

Morgan and Forrest understood that cavalry could be more effective when used for quick strikes on enemy supply lines rather than employed for only picketing and scouting. During the first two years of the Civil War, cavalry attacks of this kind had proven to cause disruptions to enemy campaigns. For example, General Grant’s first campaign to capture Vicksburg was halted when Confederate major general Earl Van Dorn’s cavalry raid destroyed Grant’s base of supplies at Holly Springs, Mississippi, in December 1862. Grant learned from Van Dorn’s success. He sent Union colonel Benjamin Grierson on an April 1863 cavalry raid from LaGrange, Tennessee, to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, to divert the attention of General Pemberton’s Confederate forces away from Grant as his army approached Vicksburg. Grierson’s Mississippi Raid not only achieved its objective but also went down in American history as one of the greatest raids of all time. Most of all, it proved the Union cavalry had risen to a level equal in strength and skill to the Confederate cavalry in the western theater of the war.

Braxton Bragg also recognized the power of the cavalry to divert the enemy’s attention away from an army. He wanted a similar diversion as Grierson’s to hold Rosecrans’s and Burnside’s attentions long enough for the Army of Tennessee to fall back safely to a better defensive position. “General Bragg,” wrote Colonel Basil W. Duke of Morgan’s command, “knew how to use, and invariably used, his cavalry to good purpose, and in this emergency he resolved to employ some of it to divert from his own hazardous movement, and fasten upon some other quarter, the attention of a portion of the opposing forces.” A leader in Wheeler’s corps offered a proposal. The officer’s name was John Hunt Morgan.

The handsome, dashing thirty-eight-year-old brigadier general hailed from a prominent pro-Confederate family in Lexington, Kentucky. One Confederate soldier asked, “Did you ever see Morgan on horseback? If not, you missed one of the most impressive figures of the war. Perhaps no General in either army surpassed him in the striking proportion and grace of his person, and the ease and grace of his horsemanship.” At six feet tall, 185 pounds, broad shouldered, with sparkling gray blue eyes and a well-trimmed black beard and mustache, he was a compelling man to behold.

John Hunt Morgan was born in 1825 in Huntsville, Alabama, to a family with Southern aristocratic ties to Kentucky millionaire John Wesley Hunt. Morgan grew up in the world of Southern high society and its definition of honor. He briefly attended T...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Maps

- Preface

- 1. “Knight on a White Horse”

- 2. Thunderbolt on the Bluegrass

- 3. Into the “Promised Land”

- 4. “The Darkest of All Nights”

- 5. “One Continual Fight”

- 6. “Better Make the Best of It”

- 7. Five Hundred Volunteers

- 8. “Already Surrendered”

- Epilogue. Lightning War

- Bibliography

- About the Author