- 115 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

On April 19, 1861, the first blood of the Civil War was spilled in the streets of Baltimore. En route to Camden Station, Union forces were confronted by angry Southern sympathizers, and at Pratt Street the crowd rushed the troops, who responded with lethal volleys. Four soldiers and twelve Baltimoreans were left dead. Marylanders unsuccessfully attempted to further cut ties with the North by sabotaging roads, bridges and telegraph lines. In response to the "Battle of Baltimore," Lincoln declared martial law and withheld habeas corpus in much of the state. Author Harry Ezratty skillfully narrates the events of that day and their impact on the rest of the war, when Baltimore became a city occupied.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Baltimore in the Civil War by Harry A. Ezratty in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER I

Baltimore on the Eve

of the Pratt Street Riot

April 1, 1861

To use the Bible to support slavery is analogous to using the Bible to support polygamy or other outmoded practices.

—Rabbi David Einhorn, Congregation Har Sinai, Baltimore, April 1, 1861

Baltimore was Maryland’s major city before the Civil War. It was America’s fourth-largest city (some historians say the third) with a population of 212,000. Like many important seaports, the city was home to a diverse mix of people. Baltimore’s busy harbor, known as “the Basin,” curled along the Patapsco River, which emptied into the northern end of the Chesapeake Bay. Baltimore’s location, to the south and west of New York and Philadelphia, placed foreign imports and the city’s manufactured products closer and more accessible to the western markets of Virginia, western Pennsylvania and Ohio and to Southern states as far south as Florida.

Baltimore’s harbor bustled with maritime trade. Brawny stevedores and vans drawn by horses and carters hauled tons of commercial cargo along the city’s docks, piers, warehouses and sheds. The white sails and the bare, furled masts of scores of tall wooden sailing ships could be seen from Pratt and Lombard Streets, important commercial thoroughfares running east and west through the city’s downtown area parallel to the docks. A rail line ran along Pratt Street. It had been laid down to allow railway cars, pulled by horses, to connect the President Street Station and other depots in the city to the Baltimore and Ohio’s (B&O) Camden Station. That station was the city’s only departure point to the South. It was located on the southwest side of Baltimore.

A view of Baltimore Harbor from Federal Hill. Courtesy of Enoch Pratt Free Library, Maryland’s State Resource Center, Baltimore, MD.

Baltimore was also the South’s largest city, since it was located forty miles below the Mason-Dixon line, the imaginary line America accepted as the geographic, cultural and political division between the North and the South. Baltimore was so close to the North, however, that it gave rise to the well-known saw that “Baltimore is the northernmost Southern city and the southernmost Northern city.” The city may have been Southern, as it was located in a slave state, but its varied climate resembled that of its Mid-Atlantic neighbors—Philadelphia, Trenton and New York—with snow and frigid winters. Yet Baltimore’s summers were also hot and humid like its steamier Southern sister cities of Savannah, Charleston and New Orleans. Trees and flowers that grew only in the North grew in Baltimore, and trees and flowers thriving only in the South could also be found there. Even the distinct Baltimore accent could be ascribed to neither the South nor the North. Maryland’s citizens were divided on the issues of slavery, states rights and secession, the same rifts that split the North from the South.

As were Kentucky, Tennessee, Missouri and Delaware, Maryland was a border state, politically and geographically wedged between North and South. All the border states had populations that, like Maryland’s, were divided on issues of slavery and states’ rights. Maryland was home to 90,000 slaves, yet Baltimore, its largest city, counted only 2,118 men and women in bondage. Baltimore also hosted about 25,000 free blacks, the largest community of its type in the United States. These freedmen were an important part of the city’s workforce.

Baltimore’s citizens were politically and emotionally divided between pro- and anti-South and slavery. There were clashes as passions ran high about these issues and the right of a state to secede from the Union.

One religious leader, Rabbi David Einhorn, received threats for his long, outspoken and impassioned antislavery stand. While he would not yield to threats—even after the office of his antislavery newspaper, the Sinai, was destroyed—he was eventually forced to move to Philadelphia to ensure his family’s safety. Union soldiers told him that he and his family were in danger because of his antislavery position. Within a month after the Pratt Street Riot, Einhorn was escorted out of the city under guard and on his way to Philadelphia. In contrast, Einhorn’s colleague, Rabbi Bernard Illowy, left Baltimore to take up a pulpit in New Orleans, where he felt more comfortable with his new proslavery congregation. The problem was not limited to the Jewish community. A Lutheran minister’s loyalty was questioned by the military because in a Sunday sermon he questioned the necessity of killing Southerners.

After Lincoln’s election in 1860, many Marylanders clearly intended to try to force the state to secede from the Union. Of the almost 90,000 presidential ballots cast in Maryland among the four candidates (Abraham Lincoln, John Breckenridge, John Bell and Stephen Douglas), Lincoln limped in a poor last with only 2,294 votes. Breckenridge, the proslavery candidate, garnered the largest number of votes: 42,497. Lincoln was not well thought of in Maryland.

Despite the state’s pro-Southern orientation, Maryland’s governor, Thomas Hicks, was a sometime pro-Union member of the American Native Party, also called the Know-Nothings. After Lincoln’s election and the secession of the Southern states, Hicks was under great pressure by his pro-South legislators to call a special session of the legislature. They wanted to fix Maryland’s position on the issue of secession. He was holding them at bay, but he knew he would soon have to yield to them. Aside from its strategic location with respect to the nation’s capital at Washington, should there be a war, Baltimore’s industry would be vital to an agrarian South. Secessionists wanted to move this important prize into the Confederate corner.

By April, 1, 1861, seven states, rejecting Lincoln as their president, broke away from the Union (South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Texas and Louisiana). They assumed the name Confederate States of America (CSA), electing Jefferson Davis, a West Point graduate, one-time secretary of war and most recently a resigned United States senator from Mississippi, as their president. At political rallies, in newspaper editorials and at street corner meetings held all over Baltimore, people debated the possibility of Maryland breaking away from the Union. The troubled city was poised to see what its closest Southern neighbor, Virginia, which had yet to act, would do. Whose side would she choose?

A threatened Rabbi David Einhorn leaves Baltimore with his family. Courtesy of the Jewish Museum of Maryland.

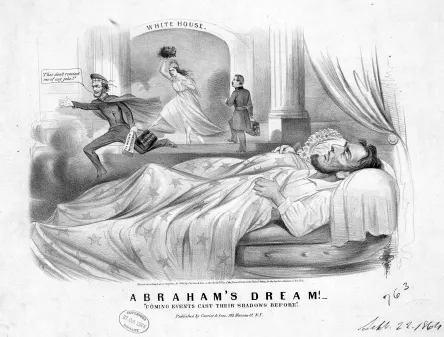

Lincoln dreams of his stealthy entrance into Baltimore in 1861. Note the Scotch cap and cloak he used as a disguise. Courtesy Library of Congress.

Baltimore was also the birthplace and an important center of America’s commercial railroading. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) was the first in America to carry passengers for hire. The B&O had an important economic impact on the city as its rail systems ran in all directions out of the city. Its main depot at Camden Station, built in 1856, was the sole rail link to the nation’s capital. Despite the importance of the B&O and the several other railroads that also serviced the city, the Baltimore City Council passed an ordinance in 1831 forbidding steam engines to operate within city limits. Trains running into Baltimore’s many stations located around town required passengers to detrain and take horse-drawn cars along the Pratt Street rails to Camden Station. This law would play an important role in the Pratt Street Riot developing into such a bloody mêlée.

There was a brisk shipbuilding industry, and the city was an important center for the manufacture of flour and the heavy sailcloth used for sailing ships. Many of the manufacturing facilities were powered by mills along the banks of the Jones Falls, a river running into the city and emptying into the Patapsco River. Fishing ships made their way to Baltimore from the Chesapeake Bay, sailing up the Patapsco and unloading heaps of fresh fish, crabs, oysters and other seafood. Their catches were destined for the city’s tables and those of surrounding communities.

The Jones Falls, looking south, running into Baltimore Harbor. Note the factories. Courtesy of Enoch Pratt Free Library, Maryland’s State Resource, Baltimore MD.

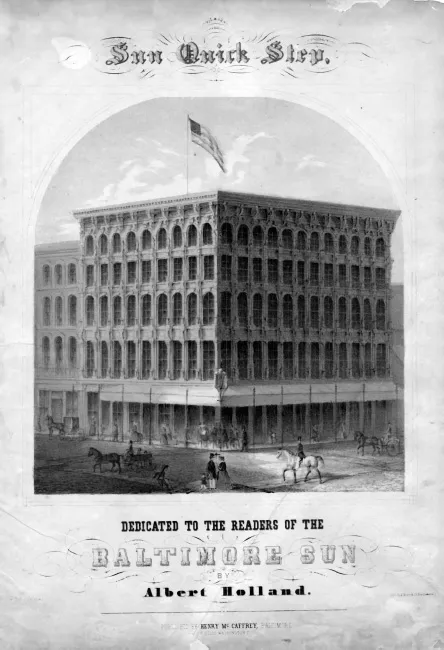

Dominating the busy, downtown commercial corner of Baltimore and South Streets was a large and modern architectural wonder, the five-story Sun Iron Building. It was designed by pioneer architect James Bogardus, a leading exponent of cast-iron façade buildings. The structure was the first of America’s tall buildings using cast iron for structural support. Completed in 1851, it was home to the Sun, one of the city’s leading newspapers, which, while pro-South, was not an advocate of secession. The building held everyone’s attention from its first day. Designed with innovative arches and vaulted arcades, the radical design changed the face of the city’s business district in the decade since its completion. Office buildings and factories of similar design were sprinkled throughout downtown Baltimore. But it was the Sun Iron Building that tourists and students of architecture came to gaze upon with awe and academic appreciation. Along the outside of the building’s second floor, Bogardus placed two large, iron plaques depicting Benjamin Franklin and George Washington, both of whom looked out upon the citizens of this busy city.

The innovative Sun Iron Building at the corner of Baltimore and South Streets, just steps from Pratt Street. Courtesy Enoch Pratt Free Library, Maryland’s State Resource Center, Baltimore, MD.

The sitting chief justice of the United States Supreme Court, Roger B. Taney, who would play a historic role in the Pratt Street Riot, was a Marylander and a former slave owner who once lived in Baltimore. Much of his popularity among Southerners was based on his 1857 decision in the Dred Scott case. In this opinion, Taney held that slaves could not be American citizens, had no standing to sue in the federal courts and could not be taken away from their owners or become free merely because they resided in a nonslave state. Taney was the brother-in-law and former law partner of Francis Scott Key, the distinguished Baltimorean who wrote “The Star Spangled Banner.” During the naval War of 1812, at the Battle of Baltimore, Key happened to be aboard a British warship anchored off Fort McHenry. He was on a government errand negotiating the exchange of prisoners of war. When the sun rose after a fierce nighttime battle, he saw the American flag still flying above Fort McHenry. It inspired him to write what became America’s national anthem.

Fort McHenry itself was an important reminder to Baltimoreans and the rest of the nation of how, in this city, a young and raw country stood firm against one of the world’s most powerful military machines. For it was here that ordinary citizens fought alongside soldiers, avenging America’s honor. Together they beat back the British invaders who had, shortly before assaulting Baltimore, torched the White House to the country’s humiliation. The proud city erected a monument to that victory called the “Battle Monument.” It stood in Monument Square, an important social and political section of the city.

Every large city along the Atlantic seaboard was home to immigrants, and Baltimore was no exception. After New York and Boston, Baltimore was the third most popular port of entry for Europe’s immigrants. The Irish settled mainly in the poor southwest section of the city, close to the B&O railroad facilities, where many of the lucky ones found work. Germans also found homes throughout the city when they were driven from their country by the religious divisions and the political upheavals of the Revolution of 1848.

The statue of Justice Roger Taney in Mt. Vernon Square. Under his left arm rests the Constitution. Photo courtesy of Marcus Dagan.

The Battle Monument commemorating the Battle of Baltimore, 1814. Courtesy of Enoch Pratt Free Library, Maryland’s State Resource Center, Baltimore, MD.

Among some of the city’s prominent landmarks were Federal Hill, Washington Monument and the Phoenix Shot Tower. Federal Hill, a promontory located on the south side of the harbor, was in a working-class neighborhood. From the top of the hill, there were stunning views of the harbor and Baltimore’s business district. From Federal Hill, one could also look out to the northern edges of the city’s limits and see America’s first monument dedicated to George Washington. Completed in 1829, the monument rose on the crest of a ridge in the city’s Mt. Vernon district, where handsome nineteenth-century mansions and brownstones of the well-to-do lined the lovely neighborhood’s quiet streets. The marble spire is topped with a statue of George Washington, who does not wear his military uniform but is wrapped within a classic, flowing Roman toga. In 1861, when Baltimore’s homes and commercial buildings were uniformly low, sailors and passengers aboard ships entering the harbor could look a mile up the rise at Charles Street, one of the city’s great avenues, and see America’s first president standing atop his gleaming white monument.

In 1861, the Phoenix Shot Tower, constructed of one million red bricks and reaching a height of 234 feet, was America’s tallest structure. Built in 1828, it was still being used commercially. Pistol and rifle shot were manufactured there by dropping molten lead from the top of the tower into a sieve. The hot liquid lead traveled all the way down the tall tower into a vat of cold water, finishing up as pellets destined for use as pistol and rifle balls.

The city was also home to notorious gangs with colorful names like the Plug Uglies, the Riff Raffs, the American Rattlers and the Blood Tubs. The Blood Tubs were said to have ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword, by Martin Perschler

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue

- I. Baltimore on the Eve of the Pratt Street Riot: April 1, 1861

- II. A Prelude to Baltimore’s Bloody Riot: April 12, 1861, Fort Sumter, Charleston, South Carolina

- III. Trying to Prevent a Riot: April 15 to April 18, 1861

- IV. A Plan to Assassinate Lincoln

- V. The Civil War’s First Blood: Pratt Street, Baltimore, April 19, 1861

- VI. More Violence: Baltimore Is Cut Off from the North, April 19–27, 1861

- VII. Lincoln Declares Martial Law: April 27 to May 13, 1861

- VIII. Some Questionable Arrests

- IX. The Story of Habeas Corpus

- X. Baltimore: A Prisoner of Its Geography

- XI. Lincoln’s Last Ride: The Aftermath of the Pratt Street Riot, April 21, 1865, to Present

- Appendix I. The Lives of Some of the Participants After the Pratt Street Riot, April 21, 1865, to Present

- Appendix II. Pratt Street Riot Markers

- Sources and Materials Used in Research

- About the Author