- 112 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

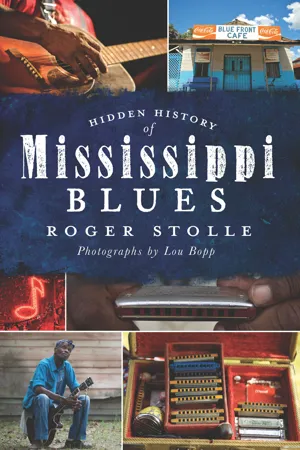

Hidden History of Mississippi Blues

About this book

Although many bluesmen began leaving the Magnolia State in the early twentieth century to pursue fortune and fame up north, many others stayed home. These musicians remained rooted to the traditions of their land, which came to define a distinctive playing style unique to Mississippi. They didn't simply play the blues, they lived it. Travel through the hallowed juke joints and cotton fields with author Roger Stolle as he recounts the history of Mississippi blues and the musicians who have kept it alive. Some of these bluesmen remain to carry on this proud legacy, while others have passed on, but Hidden History of Mississippi Blues ensures none will be forgotten.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hidden History of Mississippi Blues by Roger Stolle in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

BLUES BEGINNINGS

The Archaeology of a Culture Barely Noted

“INDIANA JONES” OR “MISSISSIPPI PEABODY”?

Today, the Mississippi Delta is flat as a pancake and relatively treeless. It is mostly farmland, except for the occasional little town. Many of the old downtowns feature big brick buildings, sometimes worn and roofless, towering like Roman ruins from a boomtown past. These monuments now stand and remind us of the region’s glory days done gone—the days when cotton was king.

Before this Delta landscape grew tired, before the days of King Cotton—before all of that—there were Native American tribes throughout the region. There were dense forests and swamps full of panthers and bears. There were tall Indian mounds and rich, long-standing cultures we can only glimpse from the twenty-first century.

In 1901–1902, the Indiana Jones of his day, Charles Peabody, came to Coahoma County in Mississippi in search of lost remnants from a past Native American civilization. What he found was more than just a pile of old bones or pottery shards. He found an altogether different culture as well, very much alive and (unbeknownst to him) in its formative days. It was an artistic foundation that was destined to change the future of popular music forever.

Fortunately for us, Peabody was from the north—from the Peabody Museum of Harvard University, to be exact—so this was all new and strange to him. Unlike many of his fellow white men who hailed from the highly segregated Mississippi Delta, Peabody didn’t take what he observed for granted or think it unimportant simply because it was a product of the local African American population. (Remember, slavery was still a warm memory in the south at that point, having ended less than forty years before.) As a scientist, Peabody’s radar was always on, and what he observed felt compelling, maybe even important.

THE FIRST ARTICLE ON “BLUES” MUSIC?

A year after his return from the Delta, Peabody still could not forget his brush with black southern culture. In the summer of 1903, with the memories still fresh and vibrant, he published “Notes on Negro Music” in the Journal of American Folk-Lore. It is true that he never used the actual word “blues” to describe the music he heard (largely because no sheet music or record labels had yet coined the term “blues” to describe the genre). Still, through his vivid descriptions of the musicians and music, with consideration of the observer’s time and place, it now seems clear that the work songs, hymns and “ragtime melodies” he witnessed were either the fringes of a blues art form already in place or the recipe for a blues feast soon to come.

Viewed over one hundred years since, Peabody’s anecdotal writings are a treasure trove of musical folklore. For us, sitting here today, they are a bit like a blues excavation of an incredible archaeological find.

From “Notes on Negro Music”:

I was engaged in excavating…[an Indian] mound in Coahoma County, northern Mississippi. At these times we had some opportunity of observing the Negroes and their ways at close range…Busy archaeologically, we had not very much time left for folk-lore, in itself of not easy excavation, but willy-nilly our ears were beset with an abundance of ethnological material in song—words and music…The music of the Negroes which we listened to may be put under three heads: the songs sung by our men when at work, unaccompanied; the songs of the same men at quarters or on the march, with guitar accompaniment; and the songs, unaccompanied, of the indigenous Negroes—indigenous as opposed to our men imported from Clarksdale, fifteen miles distant.

Peabody also took the time to document some of the song lyrics he heard during his time in the Delta, and it is mind boggling how some of the lines still show up in present-day blues songs. For example, “Some folks say preachers won’t steal, but I found two in my cornfield,” shows up more or less verbatim in a recorded song popularized by Muddy Waters (“Can’t Get No Grindin,’” 1972) and is still sung today by Mississippi-born blues singers like Big George Brock and Jimmy “Duck” Holmes. “They arrested me for murder, and I never harmed a man” shows up in several later blues recordings, including Eddie Boyd’s 1953 classic “Third Degree,” also covered by rock-blues guitarist Eric Clapton in 1994.

One a final note, Peabody made this curious observation, regarding the plentitude of song within the black community and its deficit elsewhere: “They are in sharp contrast to the lack of music among the white dwellers of the district.”

Even then, the musical foundation of the Delta’s African American population, if primitive by modern standards, was culturally rich and rapidly developing.

THE FATHER OF THE BLUES

If you want a nickname or a description of yourself to stand the test of time, take a lesson from W.C. Handy. Put it in a book title.

Handy’s 1941 autobiography, entitled Father of the Blues, forever married the author to his brilliant title, confusing decades of newbie blues fans in the process. (Handy did not invent or “father” the blues, though he did help popularize the art form, as we shall see.)

William Christopher Handy was a respected African American musician, author and bandleader in the early part of the twentieth century. Born in Alabama in 1873, he took an early interest in education and music as a way to escape his poor upbringing, later becoming both a teacher (albeit briefly) and a successful musical composer.

Besides gaining his “Father of the Blues” moniker via the title of his autobiography, Handy further secured the nickname through a tantalizing story of discovery recalled within the text. It is his first Delta blues memory, circa 1903 (the same year he moved to Clarksdale, Mississippi, and the same year Peabody published his observations above):

One night in Tutwiler [, Mississippi, fifteen miles southeast of Clarksdale], as I nodded in the railroad station while waiting for a train that had been delayed nine hours, life suddenly took me by the shoulder and wakened me with a start. A lean, loose-jointed Negro had commenced plunking a guitar beside me while I slept. His clothes were rags; his feet peeped out of his shoes. His face had on it some of the sadness of the ages. As he played, he pressed a knife on the strings of the guitar in a manner popularized by Hawaiian guitarists who used steel bars. The effect was unforgettable. His song too, struck me instantly. “Goin’ where the Southern cross the Dog.” The singer repeated the line three times, accompanying himself on the guitar with the weirdest music I had ever heard.

Handy went on to ask the musician about the song’s meaning. From the man’s reply, Handy came to understand that the singer was traveling to where the Yazoo Delta Railroad—nicknamed the “Yellow Dog”—crossed the Southern Railway in Moorhead, Mississippi, approximately fifty miles from Tutwiler.

From the musician’s rough exterior and primitive slide guitar technique to the song’s railroad subject matter and oft-repeated lines, it appears that Handy’s firsthand observations provided the world’s earliest written account of a solo, country bluesman at work.

Still, it wasn’t this first blues encounter that led Handy to eventually name his autobiography (and himself) Father of the Blues. An epiphany still needed to occur—one that would turn the music he first judged “weird” into something that started to make sense: dollars and cents.

A BLUES COMPOSER IS BORN

While living in Clarksdale, Handy and the Knights of Pythias (his nine-piece African American orchestra specializing in the popular tunes of the day) took a gig in nearby Cleveland, some forty miles south. It was there that Handy experienced firsthand the profit potential of this newly crowned genre.

As he recalled in his autobiography:

I was leading the orchestra in a dance program when someone sent up an odd request. Would we play some of “our native music,” the note asked. This baffled me. The men in this group could not “fake” and “sell it” like minstrel men. They were all musicians who bowed strictly to the authority of printed notes…A few moments later a second request came up. Would we object if a local colored band played a few dances?…That was funny. What hornblower would object to a time-out and a smoke—on pay? They were led by a long-legged chocolate boy and their band consisted of just three pieces, a battered guitar, a mandolin and a worn-out bass. The music they made was pretty well in keeping with their looks…Their eyes rolled. Their shoulders swayed…I commenced to wonder if anybody besides small town rounders and their running mates would go for it. The answer was not long in coming. A rain of silver dollars began to fall around the outlandish, stomping feet…[Before long,] there before the boys lay more money than my nine musicians were being paid for the entire engagement. Then I saw the beauty of primitive music…That night a composer was born.

Born, indeed. According to Handy, that was 1905. Clearly, based on this and his earlier exposure to this “primitive music,” blues had not only a foundation in the Delta by that point but also a following. If it could be popular there, then with a little smoothing and shaping, perhaps it could gain a following elsewhere.

THE FIRST “BLUES SONGS”

Nearly a decade after Handy’s first Delta blues exposure, he published sheet music for a song entitled “Memphis Blues” (September 1912). While some have identified this as the first published blues composition, that first actually goes to Hart A. Wand and his song “Dallas Blues,” published in March of the same year. Of course, neither composer would have called himself a “bluesman” at the time. Wand was actually a white man of German heritage who hailed from Topeka, Kansas, and grew up in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. According to historian Samuel Charters, in his groundbreaking 1959 book The Country Blues, Wand probably first heard his tune (or at least its title and possibly its melody) from an African American porter from the south who worked for the young Wand’s father.

While Handy’s “Memphis Blues” was not, in fact, constructed as a typical blues song and included only a taste of typical blues lyricism, Wand’s composition was presented as a twelve-bar blues and contained several bluesy lines.

Perhaps neither composition was truly a “blues song” in the cultural sense, but both helped to standardize a label for this burgeoning art form. Finally, this mysterious music of the American south had a name printed in indelible ink: the blues.

IS THIS THE HISTORY OF THE BLUES?

Why is it that we have to dig like Indiana Jones to find the beginnings of blues history? If what we call blues today began only a hundred-plus years ago, shouldn’t there be more records (no pun intended) or eyewitness accounts in the literature? More documentation?

Again, note that Peabody (and, for that matter, Handy) was not from Mississippi or the Delta region where blues seems to have first appeared. This was a tough, fairly closed society at that time, and segregation was in full force. Frankly, it is very doubtful that most white people living in Mississippi during that era would have cared about the folk music of an illiterate black workforce. And let’s face it: at that time, in this part of the country, it would have been whites who were writing down history. It took outsiders to note it, if almost incidentally, for posterity.

In the end, the furthest back we can take American blues history (without following its roots to Africa) seems to be around the turn of the twentieth century. It would take the coming of hit sheet music in the 1910s, popular records in the 1920s and AM radio in the 1930s and beyond to truly crystallize the blues as an important, recognized musical genre. And it would take the migration north of hundreds of thousands of African Americans, starting around 1915 (and reaching its apex in the 1950s), to spread the music—once and for all—from the cotton fields of Mississippi to the rest of the world.

Chapter 2

COTTON LIVES

Plantations, Floods and the Blues Migration

IS THE “MISSISSIPPI DELTA” EVEN A DELTA?

At my Cat Head Delta Blues & Folk Art store in Clarksdale, Mississippi, I often field questions like, “Why is the Delta called a delta?” Or, “What area does the Mississippi Delta cover?” The first question is appropriate because most reference books define a delta differently than the Delta we refer to in blues lore. The Merriam-Webster English Dictionary, for example, defines a delta as “something shaped like a capital Greek delta; especially, the alluvial deposit at the mouth of a river.” Not very helpful in our case since our blues Delta isn’t exactly triangular and ends some three hundred miles north of where the Mississippi River mouth empties into the Gulf of Mexico.

What the Mississippi Delta refers to, especially when discussed in a blues context, is northwest Mississippi’s alluvial plain situated between the Mississippi and Yazoo Rivers. It appears quite pronounced on a topographical map of the region. Created by centuries of erosive river flooding and the receding waters of the Western Hemisphere’s last great ice age, the Mississippi Delta is largely flat and richly deposited with topsoil sediments from all points north.

Historian James C. Cobb defined the Mississippi Delta as “actually more of a diamond or oval than deltoid in shape…ap...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword, by Jeff Konkel of Broke & Hungry Records

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. Blues Beginnings

- 2. Cotton Lives

- 3. Race Records

- 4. Radio Days

- 5. The Crossroads

- 6. Juke Joint

- 7. The Interviews

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author and Photographer