eBook - ePub

Italians Swindled to New york

False Promises at the Dawn of Immigration

- 177 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The unification of Italy in 1861 launched a new European nation promising to fulfill the dreams of Italians, yet millions of poor peasants still found themselves in economic desperation. By 1872, an army of speculators had invaded the countryside, hawking steamship tickets and promising fabulous riches in America. Thousands of immigrants fled to the New World, only to be abandoned upon arrival and forced to find work in hard labor. New York placed victims of deception at the State Emigrant Refuge on Ward's Island as the secretary of state and the Italian prime minister sought to intervene. Through steel-eyed determination, many surmounted their status and became leaders in business and culture. Authors Joe Tucciarone and Ben Lariccia follow the early stages of mass Italian immigration and the fraudulent circumstances that brought them to New York Harbor.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Italians Swindled to New york by Joe Tucciarone,Ben Lariccia in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Italian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1.

PRELUDE

An Italian American is any citizen of the United States who is descended from an Italian ancestor. Numbering over 17 million, they comprise the fifth most populous ethnic group in the country. This imposing presence belies the fact that they were not always so numerous in America. Immigration from Italy was virtually nonexistent during the first half of the nineteenth century. For example, between 1820 and 1830, an average of only 44 Italians came to the United States each year.3 When Giuseppe Garibaldi’s army swept through Sicily and the Neapolitan provinces in 1860, a mere 1,019 residents of the peninsula landed here. With the outbreak of the American Civil War, the rate fell sharply and remained below 1,000 per year until 1866.

In 1870, the count rose above 2,000 for the first time and reached 4,190 in 1872. Although it seems impressive, this figure is dwarfed by the totals from other European countries. In that year, for every Italian immigrant to the United States, there were 16 who hailed from Ireland. And Germany, which led all nations, outstripped arrivals from Italy by more than 30 to 1.4 Still, 1872 marked a watershed in the migration of Italians to America. It was really the beginning of the great wave of Italian immigration that would eventually outpace all other countries.

THE FIRST GENERATION OF ITALIANS IN THE UNITED STATES

The characteristics of the first generation of Italian arrivals contrasted sharply with those of later immigrants, mainly poor farmers, who followed in the mass immigration of the 1870s and beyond. Among these early immigrants, a number of artisans and artistes made their mark. These were stonecutters, painters, musicians and other trained professionals whose skills were in fashion. In addition, they were joined by the occasional émigré who made the United States a temporary or permanent home.

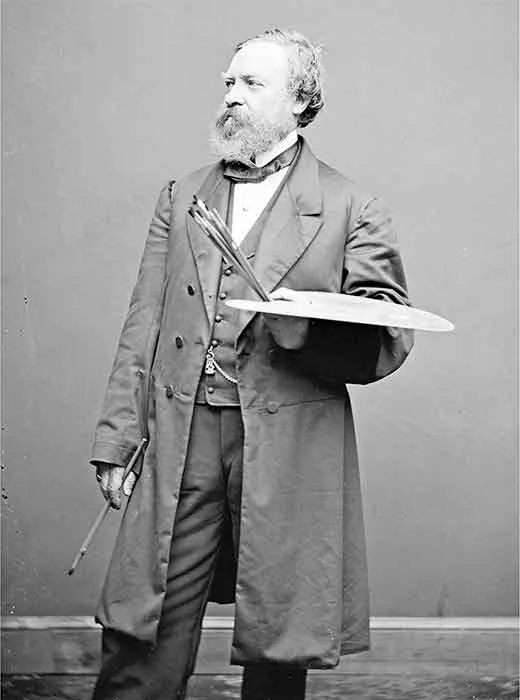

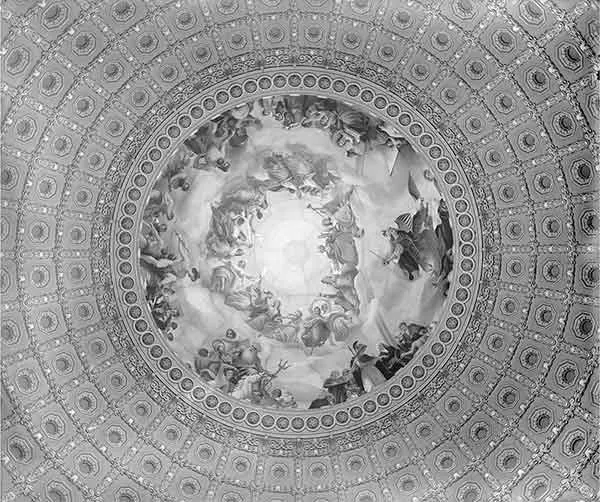

Italian high culture, encompassing the best achievements of European civilization, found a welcome home in the United States, especially among the new republic’s elite. Thomas Jefferson employed Italian masons in the construction of Monticello, the word itself from Italian for “a little mountain.” Constantino Brumidi’s frescoes and paintings, especially those adorning the U.S. Capitol, continue to enthrall. Italians brought to the young, rough-hewn United States the gifts of an educated, cosmopolitan Europe. Moreover, in the works of Rossini and Verdi, Americans found solidarity in the themes of mid-nineteenth-century Italian opera that extolled national independence and triumph over tyranny.

In the field of music, Italian contributions to the young United States were considerable. In September 1805, at the invitation of President Jefferson, fourteen Italian musicians arrived with their wives and children aboard a U.S. Navy ship in Washington, D.C. Among the passengers was Gaetano Carusi, the leader of the group. Since its founding in 1798, the United States Marine Band had specialized in playing fife and drum music for the enjoyment of corps members and the public. With the addition of these and future Italian musicians, a new and more varied repertoire made its appearance. In 1833, Lorenzo da Ponte, an accomplished librettist, founded the first opera house in New York City. These are just a few of the many Italians who contributed to an American audience eager for European music.

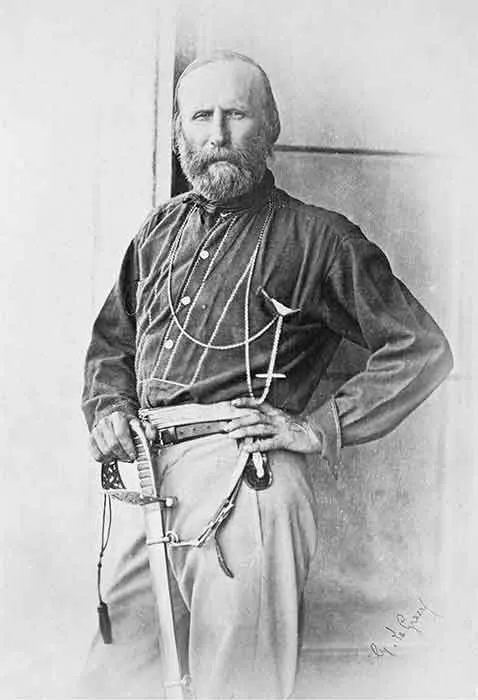

The institution of slavery on American soil notwithstanding, European liberals saw the United States as a beacon for Republicanism and a haven for freedom fighters. Several Italians of political note made the United States home, at least temporarily. Among them was Giuseppe Garibaldi, Italy’s most celebrated military hero and revolutionary mercenary. During the U.S. Civil War, Italians enrolled in the Confederate army as well as on the Union side. Many in the latter group served as members of the popularly called “Garibaldi Guard,” really the Thirty-Ninth New York Volunteer Infantry.

Constantino Brumidi. Brady-Handy Photograph Collection, Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

Apotheosis of Washington, painted by Brumidi on the dome of the U.S. Capitol rotunda. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

Another Italian independence hero, Luigi Palma di Cesnola, veteran of Italy’s first war of independence, led the Fourth New York Cavalry Regiment in the American conflict.

Early in the war, the North suffered several stinging defeats at the hands of the Rebels. In response to the dire situation, President Lincoln and Secretary of State William Seward made overtures, in the end unsuccessful, to recruit Garibaldi, who expressed a desire to be appointed commander-in-chief of the entire U.S. military. The Italian hero demanded the abolition of slavery as a prerequisite for his service, an objective that was not attained until December 1865.

In the years before 1870, if Americans knew anything about the few Italians in the United States, it would have been most likely in reports about craftsmen, artists or émigrés. In coming years, deteriorating conditions in Italy, aided by technological advances in steamship navigation, would send a stream of unlettered rustics to the Americas.

Giuseppe Garibaldi, 1860. Photograph by Gustave Le Gray. Courtesy of Getty’s Open Content Program.

POLITICAL CHANGE AND SOCIAL CHAOS

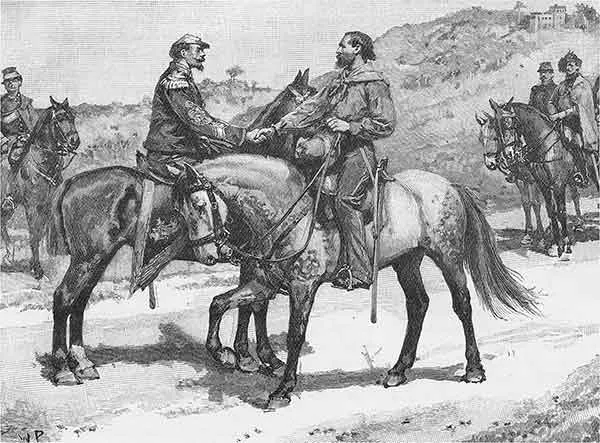

Prior to 1861, the Italian peninsula and Sicily were separate political states. In the early part of the nineteenth century, the idea of Risorgimento, a resurgent, united Italy, gained popularity, especially among the educated and the middle classes. What was to become the modern Kingdom of Italy had its incubation in the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia, governed by monarchs from the House of Savoy. Beginning in 1859, the Piedmontese ruler, Victor Emmanuel II, added Lombardy, Tuscany and the Papal States in the drive to win political unification. In 1860, Giuseppe Garibaldi’s culminating military victory over the Bourbon-ruled Kingdom of the Two Sicilies set into motion the annexation of southern Italy to the territory under the command of Piedmont-Sardinia. A handshake (stretta di mano) exchanged by Garibaldi and Victor Emmanuel, both mounted on horseback, effected the transfer. With no strings attached, unification forces gained the huge southern territory. A year later, the new Italian nation was born as the Kingdom of Italy, a constitutional monarchy, with Victor Emmanuel II installed as king.

As to the former Bourbon realm, the region continued with the idyllic sobriquet Mezzogiorno, Italian for “midday.” But contrary to its poetic designation, conditions were far from perfect, with glaring differences in wealth and resources, some of which continue today. Centuries-old political and geographic divisions combined to make southern Italians economically and culturally distinct from their brethren to the north. These differences would severely challenge attempts to create a united country.

At first, the Kingdom of Italy offered little to soften the blow of political and cultural change hitting the South. As a result, emigration increasingly seemed the only hope of escape. Those attempting to leave were overwhelmingly impoverished men who were illiterate, unfamiliar with English and did not speak standard Italian. This difference in makeup with the previous generation of immigrants affected how Americans would view the growing wave of destitute newcomers appearing in New York and other northeastern ports.

As the political phase of unification drew to a close in 1861, reports of brigandage entered the press coverage of the day. Although the existence of bandits is attested to decades before the unification of Italy, now the ranks of the briganti grew as a result of radical changes unleashed by land privatization and new taxes. With the shock of annexation to the Kingdom of Italy, the Mezzogiorno broke out in a series of uncoordinated revolts. From the grist tax—really a hated tax on bread—to the imposition of Piedmontese5legal reforms such as compulsory military service, the countryside was in rebellion. Americans took note and closely followed the events.

“Meeting of Garibaldi and Victor Emmanuel at Teano,” 1860. Alamy Stock Photo.

In the mountains and forests, former soldiers of the defeated Bourbon army joined numbers of landless farmers—men and women—in attacking the new government and the galantuomini, or rising middle class, who were identified with it. Reports of kidnapping and murder generated an avid readership of the U.S. press. The grisly news dispatches continued as Rome responded with an iron hand, while remnants of the old order and the Vatican gave moral support to the brigands.

With the onset of extremely bad economic times, several bandit groups organized to take justice into their own hands, often pillaging and kidnapping along the way. In response, King Victor Emmanuel II sent 100,000 troops to subdue the rebellious territory. His soldiers killed thousands, among them many innocents. In the South, Carmine Crocco, one of the most notorious of the brigands, organized a guerrilla army of 2,000 to attack the newly formed country. Crocco’s Army and other highwaymen were a danger to public safety and responsible for committing atrocities. People stayed inside behind barred doors.

“Full-length portrait of a bandit in traditional Ciociaria dress,” circa 1875. Alinari Archives.

The August 1866 issue of Harper’s Magazine carried a ten-page review of William John Charles Moens’s “Three Months with Italian Brigands.” The story created a romanticized image of Italian outlaws for the American reading public. It described the capture of British traveler William Moens by captain Gaetano Manzo and his troop of briganti. Manzo was cast as a gentlemanly rogue who treated his captive with civility. When Moens’s ransom had been secured, Manzo collected a few coins from his comrades so that when he was freed, Moens could “go to Naples like a gentleman.”6 As Moens was released, Manzo extended his hand in friendship. Other, less favorable accounts of brigandage reached readers, painting the ruffians with brutish strokes:

The real brigand is a brutal, ignorant, stolid murderer—eating coarse food, sleeping on the ground in all weathers, chased from place to place, with no rest, wretched, ragged, and probably rheumatic. He certainly can lay no claim to be a hero. Generally he is content with sharing the frugal meal of some frightened peasant, and stealing small sums from native travelers. Occasionally, however, larger prey is captured. The brigand Manzi, of the province of Salerno, has just seized a Signor Marcusi, and refuses 100,000 francs ransom for him.…It appears strange that such a state of affairs should continue to exist in the midst of civilized Europe.7

As immigration from Italy increased in the early 1870s, the American reading public followed these accounts of widespread disorder taking place in the former Bourbon kingdom. Increasingly, Americans wondered how the United States would assimilate the oddly foreign Italians, economic refugees now spilling into the Port of New York.

THE DRIVERS OF MASS ITALIAN EMIGRATION

In pre-unitary Italy, especially in the old southern kingdom, schooling for peasants and agricultural laborers was rare. Under the educational program of the new regime, Parliament provided that schools be constructed throughout the Kingdom of Italy. But for many decades, analfabetismo, or illiteracy, reigned in the adult population. So, how to think of the Italians who boarded ships bound for the Americas in the last months of 1872? Were these ships of fools and gullible dullards? Or did the passengers have cause to abandon their country, only to unwittingly put their fates in the hands of land grifters, profiteers and risky sea vessels? What was happening in newly united Italy that motivated Italians to depart for northern Europe and the Americas? The following is a summary of major factors driving emigration in the 1870s. Notably, the provinces of the vanquished Bourbon regime were the regions that fed Italian emigration to the United States.

A Rising Social Class and Radical Changes in Land Ownership

The newly established and heavily indebted Kingdom of Italy saw opportunity to extract value from previously unalienable land to create a modern state. These were fields, pastures and woodlands whose titles were held by feudal barons and other aristocrats, churches and religious houses and villages. For centuries, farmers and other tenants had possessed the right of usage, in some cases by usu fructu, or free right, in others by paying a tax or rent. These properties were not on the real estate market. In 1863, the Italian government passed legislation to convert church-owned lands to securities for public sale. It was one of severa...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. Prelude

- 2. Deception

- 3. Legacy

- Epilogue: Return to New York Harbor

- Appendix I. Translation of “Avviso Agli Emigranti in America,” Gazzetta della Provincia di Molise, December 26, 1872

- Appendix II. “The Immigrant Italians; What Caused Them to Leave Sunny Italy for America,” New York Herald, January 3, 1873

- Appendix III. Testimonies of Italian Immigrants at the Ford Committee Hearings

- Appendix IV. “A Report of the Commissioners of Immigration upon the Causes Which Incite Immigration to the United States”

- Appendix V. “The Bogus Circular”

- Appendix VI. Affidavit of November 21, 1872

- Appendix VII. “Emigrants’ Wrongs; A Most Heartless Swindle,” New York Tribune, November 22, 1872

- Appendix VIII. Steamship Advertisements: August 1, 1872, through January 15, 1873

- Appendix IX. Italian Immigrants on the Steamship Holland, 1872–1874

- Appendix X. Excerpts of 1878 Emigration Regulations

- Notes

- About the Authors