- 227 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"A clear and concise telling" of America's most famous battle. "[Hoptak] has crafted a narrative that is similar to a well led tour of the battlefield" (

Civil War Librarian).

Fought on the first three days of July 1863, the Battle of Gettysburg was one of the largest and by far the bloodiest of the Civil War. Yet the importance of this great conflagration cannot be measured in numbers alone, for Gettysburg also represented a pivotal moment in the war. The battle ended General Robert E. Lee's second invasion of Union soil, and never again did a Confederate army reach that far north. Join historian John Hoptak as he narrates the fierce action between the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia and the Union Army of the Potomac at such places as McPherson's Ridge, the Railroad Cut, the Wheatfield, the Peach Orchard, Devil's Den, Little Round Top and on Culp's and Cemetery Hills.

"His expertise comes through loud and clear in his energetic prose, combining narrative and analysis in a book that enlightens novices without boring more experienced readers." — Historynet.com

Fought on the first three days of July 1863, the Battle of Gettysburg was one of the largest and by far the bloodiest of the Civil War. Yet the importance of this great conflagration cannot be measured in numbers alone, for Gettysburg also represented a pivotal moment in the war. The battle ended General Robert E. Lee's second invasion of Union soil, and never again did a Confederate army reach that far north. Join historian John Hoptak as he narrates the fierce action between the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia and the Union Army of the Potomac at such places as McPherson's Ridge, the Railroad Cut, the Wheatfield, the Peach Orchard, Devil's Den, Little Round Top and on Culp's and Cemetery Hills.

"His expertise comes through loud and clear in his energetic prose, combining narrative and analysis in a book that enlightens novices without boring more experienced readers." — Historynet.com

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Confrontation at Gettysburg by John David Hoptak in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Roads North to Gettysburg

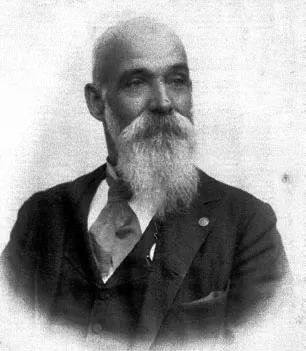

Marcellus Ephraim Jones, a thirty-three-year-old lieutenant in Company E, 8th Illinois Cavalry, fired the first shot of the Battle of Gettysburg. It was sometime around 7:30 a.m. on the morning of July 1, 1863, a Wednesday. Jones and several of his men were positioned on the advanced Union picket line several miles northwest of the south-central Pennsylvania town, on a gently rising piece of high ground then known as Wisler’s Ridge and today known as Knoxlyn Ridge. Noticing a column of approaching gray- and butternut-clad Confederate soldiers, the lieutenant borrowed a carbine from one of his soldiers, rested it on a fence rail to steady his aim and pulled the trigger. Although the bullet missed its mark, this opening shot pierced the morning silence and initiated the culminating battle of Confederate general Robert E. Lee’s second invasion of Union soil—sparking what would prove to be one of the largest clashes and by far the bloodiest battle of the American Civil War.

Or at least so goes the story accepted by most students of the battle. In the postwar years, there would be some debate over who actually fired the first shot of the Battle of Gettysburg, as several other veterans would claim that distinction. But Jones’s account has become the one most widely accepted. Still, it is a testament to the momentous nature of the battle that followed that others would make similar claims. For no other battle of the Civil War—excepting, perhaps, the war’s opening salvo fired on Fort Sumter—would there be such clamor made to identify the soldier who fired the first shot. One would, for example, be hard-pressed to name the soldier who fired the first shot at Shiloh, Antietam, Spotsylvania, Chickamauga or at any of the other great battles of the war. And on no other battlefield of the war—again excepting in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina, where a marker stands commemorating the first shot fired at Sumter—would a monument stand marking the spot where the battle’s first shot was fired, as there stands today on Knoxlyn Ridge a few miles northwest of Gettysburg. More than two decades after the battle, in an effort to further his claim and to forever note his place in the history books, Jones in 1886 helped to place a small granite marker near the spot where twenty-three years earlier he had leveled the carbine on that fence rail and fired that first fateful shot at Gettysburg.

Postwar photograph of Marcellus E. Jones. As a lieutenant in the 8th Illinois Cavalry, Jones is credited as having fired the first shot of the Battle of Gettysburg. Wheaton Center for History.

The events leading up to this much remembered first shot of the Battle of Gettysburg were set in motion four weeks earlier—on June 3, 1863—and more than one hundred miles away, when the soldiers of Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia began marching away from their campsites along the Rappahannock River, near Fredericksburg, Virginia, setting off first westward to Culpeper before turning north, passing down through the Shenandoah Valley and ultimately into Pennsylvania.

When the Gettysburg Campaign thus commenced, Americans had already been at war with one another for twenty-six months, the divided nation having witnessed more than two years of unimaginable loss and bloodshed. Tens of thousands of men in both blue and gray had already fallen, shedding their lifeblood on fields of battle across the war-torn nation. No one at its outset could have imagined what this war would become. And what no one could then know was that this awful struggle—this fratricidal conflict—would continue long after Gettysburg, for yet another two years, with all its remorseless devastation and heartache and with the casualty lists growing ever longer until, by war’s end, at least 620,000 soldiers (and thousands of civilians) were dead.

The Confederate States of America had suffered a number of critical reverses during the first two years of the conflict, and by the spring of 1863—even though history would later reveal that the war was just then only at its halfway point—there was a growing sense of urgency felt by many in the South, a sense that time was fast running out in their struggle to break away from the Union and establish their own independent nation. The number of U.S. warships and gunboats patrolling the Southern coastline continued to grow, ever-strengthening the blockade and slowly but surely strangling the Confederacy. Inflation ran rampant, while the very social and economic foundation of the Confederacy—slavery—continued to crumble, having received another heavy blow with the recently enacted Emancipation Proclamation. With this, not only had Lincoln redefined the purpose of the war from solely a political struggle to restore a divided nation to a crusade to erase the blight of slavery from the American landscape, but he had also helped to dash Confederate hopes for European recognition of their would-be nation.

Militarily, Confederate forces had also suffered a number of stinging battlefield defeats, particularly in the war’s Western Theater, where Union forces had emerged triumphant at such places as Forts Henry and Donelson and at Shiloh. Federal land and naval forces had gained control of the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers and much of the Mississippi. Nashville and Memphis had fallen, as had New Orleans, the Confederacy’s largest city and principal port. And although in the spring of 1863 one Union army in the west, under General William Rosecrans, was seemingly neutralized in Tennessee, another one, much more menacing, under General Ulysses S. Grant, continued to tighten the noose around Vicksburg, the loss of which would cut the Confederacy in two and give the Union unfettered control of the vital Mississippi River. Much of the Confederacy’s attention that third spring of the war was thus naturally focused on this deteriorating situation in the west and especially on Grant and his blue columns as they continued to close in on the critical river port.

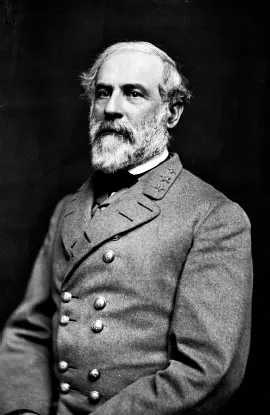

The situation for the Confederacy was considerably brighter in the war’s Eastern Theater, and with affairs looking poor elsewhere, it is little wonder why so many looked to the east, placing much of their hopes for victory on General Lee and the soldiers of his Army of Northern Virginia. Lee had assumed army command the previous year—on June 1, 1862—taking the place of Joseph Johnston, who had fallen seriously wounded at the Battle of Seven Pines, and during the next twelve months, with Lee at its helm, the Army of Northern Virginia compiled an impressive record of battlefield successes: during the Seven Days’ battles, at Second Manassas, Fredericksburg and, most recently, at Chancellorsville. Its only major setback had occurred late the previous summer in Maryland, where it had suffered defeats at the Battles of South Mountain and Antietam during Lee’s first invasion of Union territory. But despite this reverse in Maryland, Lee had triumphed more than he had failed, oftentimes against seemingly impossible odds, and had by that third year of the war emerged as the Confederacy’s greatest chieftain. It was thus on his shoulders—and those of his men—where the hopes of the Confederate nation increasingly rested.

By the spring of 1863, fifty-six-year-old Robert E. Lee had emerged as the Confederacy’s greatest military commander, having achieved a sting of stunning battlefield victories, often against great odds. Library of Congress.

Yet even with his stellar record of battlefield victories, Robert E. Lee was one of those who sensed the clock ticking. He was winning battles, to be sure, but the Confederacy was simply not winning the war, and Lee was perfectly aware that the longer the war dragged on, the lesser the chances became for ultimate victory. Lee’s own battlefield victories, spectacular though they might have been, had been costly, and any gains had proven temporary. At Chancellorsville, for example, a battle many students of the war regard as Lee’s most masterful triumph, the cost of victory was exceptionally high. There, Lee lost more than 20 percent of his army, while casualties in the Union army equaled only 13 percent. Lee had also lost his most trusted subordinate and the Confederacy one of its greatest warriors when General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson was accidentally shot down by his own troops, mortally wounded. With such a high price paid, Lee was hoping that Chancellorsville’s results would have been greater. Instead, the Union army was able to slip away and was soon holding the same positions it had occupied before the battle. One can sense Lee’s frustration when he reported that at Chancellorsville, “our loss was severe, and again we had gained not an inch of ground and the enemy could not be pursued.” Echoing this growing frustration was Lee’s second in command, General James Longstreet, who declared that such victories “were consuming us and would eventually destroy us.”

Thus, in the wake of Chancellorsville, Lee set out to achieve more. Instead of remaining on the defensive, awaiting the next Federal offensive, he would seize the initiative and lead his army north a second time. Such a movement had much to offer. It would disrupt Federal plans for the upcoming season and take the conflict away from war-ravaged Virginia, relieving the land and its people from the burdens of war. His men could also gather much-needed provisions from the lush agricultural countryside of the North, and an invasion north would trigger widespread alarm.

More than this, though, Lee went north seeking to achieve yet another battlefield victory, one with greater results. Lee realized that a victory on Union soil would capture the headlines, as all his previous victories had, and though Lee doubted that this movement would compel the Union to shift troops from the west, thereby loosening its grip on Vicksburg, it would, he reasoned, at the very least help to offset the probable loss of the Mississippi port city. A victory on Union soil would also further bolster the cries of the ever-growing number of antiwar activists in the North, clamoring for peace, and would serve to further discredit Lincoln, creating even greater opposition to his efforts at prosecuting the war. Lee thus went north not just hoping to crush the Federal army; he was also hoping to crush the North’s willingness to fight, to wear down its resolve and convince the people that this war was a contest they could not win.

In mid-May, a week and a half after the Battle of Chancellorsville and even as the remains of Stonewall Jackson were being laid to rest, Lee traveled to Richmond to plead his case directly to President Jefferson Davis and his cabinet. He found some opposition to his plan; there were those, for example, who wanted to strip troops away from Lee and send them west to help with their beleaguered forces there, while others expressed concern for the safety of Richmond should Lee go north. Still, Lee prevailed in convincing Davis of the soundness of his plan. Having received approval to undertake the invasion, the fifty-six-year-old army commander returned to his army’s campsites near Fredericksburg and prepared for the invasion. It was a bold gamble, but the payout—if successful—would be great.

Spirits were high as Lee’s gray columns began slipping away from their campsites along the Rappahannock, the men having great confidence both in themselves and in their commander. Colonel E.P. Alexander, one of Lee’s finest artillerists, echoed the sentiment of most when he wrote that “there can never have been an army with more supreme confidence in its commander than that army had in Gen. Lee. We looked forward to victory under him as confidently as to successive sunrises.” Lee, too, held great faith in his men, the recent victory at Chancellorsville again demonstrating the superb fighting qualities of his soldiers and again showing that they could triumph in the face of tremendous odds. But along with this supreme confidence there developed among the rank and file of the Army of Northern Virginia a false sense of invincibility, a sense that no matter the odds or the circumstances they could—and would—prevail. Lee felt it, too, and the very thought that his men could be defeated was one that seemed to never enter his mind in the campaign ahead.

Lee marched north with an army of seventy-five thousand men, recently reorganized into three corps. Since October 1862, his army had consisted of two corps—commanded by Lieutenant Generals James Longstreet and Thomas J. Jackson—with each numbering about thirty thousand men. Believing these organizations too large and unwieldy, Lee did some restructuring following Chancellorsville, breaking the two corps into three, with each now averaging about twenty thousand soldiers. Longstreet, a reliable soldier and a tough, determined fighter whom Lee once referred to as his “old war horse,” maintained command of the First Corps. To replace the lamented Jackson at the helm of the Second Corps, Lee selected the brave if just a bit eccentric Richard Stoddert Ewell, one of Jackson’s most trusted subordinates and a hard fighter, who was just then returning to the army after recovering from a severe wound suffered during the Second Manassas Campaign, a wound that had cost him his left leg. To lead the newly organized Third Corps, Lee chose the fiery, combative Ambrose Powell Hill, commander of the famed Light Division, whose heroics at Antietam may have saved the army from possible destruction. In recommending Hill to take the helm of the Third Corps, Lee stated that he was “the best soldier of his grade with me.”

Each of the army’s three corps was composed of three divisions of infantry, each with its own battalion of artillery, while each of the corps themselves had an artillery reserve. Rounding out the army was a “grand” division of cavalry, totaling nearly ten thousand horsemen, led by the thirty-year-old James Ewell Brown (Jeb) Stuart, who, despite his young age, had proven himself the most capable of cavaliers. All of these officers were West Point graduates, and all were hard-fighting, seasoned soldiers. Yet some questions remained, especially regarding Ewell and Hill, who were superb in divisional command but entirely untested at the higher corps level.

Lafayette McLaws’s Division of Longstreet’s First Corps led the army’s march away from Fredericksburg, setting off on June 3 for Culpeper, some thirty miles to the west. Over the next few days, most of the army’s First and Second Corps assembled there, as did Jeb Stuart’s horsemen. In addition to providing intelligence on the whereabouts of the Union army, Stuart’s task in the campaign ahead would be to provide a screen for the infantry as it moved north from Culpeper, down the Shenandoah Valley and into Pennsylvania. As the infantry prepared to move out, Stuart took advantage of the opportunity to stage two grand reviews, demonstrating the grandeur of the army’s mounted arm. “It was a brilliant day,” said one of Stuart’s aides of the first of these two reviews, “and the thirst for the ‘pomp and circumstance’ of war was fully satisfied.” Lee was equally impressed while observing the second of these reviews, declaring it a “splendid sight.” Stuart, said the army commander, “was in all his glory.”

Meanwhile, as Stuart orchestrated his mounted spectacles and as Longstreet and Ewell continued to marshal their forces near Culpeper, A.P. Hill and the soldiers of his Third Corps remained behind at Fredericksburg, occupying the attention of Union general Joseph Hooker and his Army of the Potomac, camped out on the opposite side of the Rappahannock.

As Lee’s men prepared for the invasion north, their blue-coated foes licked their wounds and took stock of the recent slugfest at Chancellorsville, assessing the performance of the army and its most recent commander. Since he had assumed command of the Army of the Potomac just a few months earlier—in the midst of what was truly a winter of despair for the Union war effort—Joe Hooker had done much to revitalize the spirit of the men, taking a number of steps to instill pride in the ranks and bolster morale. It could thus be a tribute to his efforts, then, that in the aftermath of Chancellorsville, after yet another resounding defeat, there was no real widespread demoralization in the army. Many of the boys in blue could not imagine how they were bested, and many simply could not believe that Hooker had ordered a retreat; blame for the defeat at Chancellorsville, they reasoned, rested on Hooker’s shoulders, not on theirs. Confidence remained high, and the men were still full of fight. Captain Stephen Weld may have said it best when he wrote, “This Army of the Potomac is a truly wonderful army. They had something of the English bull-dog in them. You can whip them time and again, but the next fight they go into, they are in good spirits, and as full of pluck as ever.” Concluded the Union captain, “Some day or [the] other, we shall have our turn.”

The Army of the Potomac suffered 17,000 casualties at Chancellorsville and lost thousands more in the weeks that followed as enlistments expired for those two-year volunteers who had signed up in the spring of 1861 and for those who had volunteered the summer before for a nine-month stint. But as the army marched north in pursuit of Lee, it would be reinforced by troops sent from Washington and other departments so that on the eve of the battle of Gettysburg, its total strength, at least on paper, exceeded 100,000 men. Despite its recent string of defeats, the Army of the Potomac still remained a formidable force and a truly resilient one, capably led by some of the finest brigade, division and corps commanders produced in the entire war. By the onset of the Gettysburg campaign, the cream of the Army of the Potomac was rising near the top.

Of course, at the very top was forty-eight-year-old Joseph Hooker, who, like most of his troops, was still full of fight after the drubbing at Chancellorsville. The problem, however, was developing a sound new strategy. At one point during the unfolding campaign, the ever-critical Marsena Patrick, the army’s provost marshal, confided in his diary that Hooker “is entirely at a loss what to do, or how to match the enemy, or counteract his movements.” While Patrick was admittedly no admirer of Hooker, in the wake of Chancellorsville there was considerable grumbling among many of the army’s highest-ranking officers, many having lost all faith in the capabilities of the man dubbed “Fighting Joe.” There was some cry in Washington for Hooker’s removal, but Lincoln, who appreciated Hooker’s aggres...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- A Note on Sources

- Introduction. Addressing Gettysburg

- Chapter 1. Roads North to Gettysburg

- Chapter 2. “Hard Times at Gettysburg”: The First Day, July 1, 1863

- Chapter 3. “A Scene Very Much Like Hell Itself”: The Second Day, July 2, 1863

- Chapter 4. “None but Demons Can Delight in War”: The Third Day, July 3, 1863

- Chapter 5. Roads South from Gettysburg

- Order of Battle

- Selected Bibliography

- About the Author