- 163 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Making of St. Petersberg

About this book

A wide-ranging history of this city on Florida's Gulf Coast, one of America's oldest, with numerous photos and maps included.

The Making of St. Petersburg captures the character of this bay city through its past, from the Spanish clash with indigenous peoples to the creation of the downtown waterfront parks and grand hotels. Take a journey with local historian, preservationist, and former museum executive Will Michaels as he chronicles St. Petersburg's storied history, including the world's first airline, the birth of Pinellas County, and the good old American pastime, Major League Baseball. From hurricanes to home run king Babe Ruth, the people and events covered in this work paint a rich portrait of a coastal Florida city and capture St. Petersburg's unique sense of place.Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Making of St. Petersberg by Will Michaels in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Civil Rights

Before the 1950s and 1960s, St. Petersburg’s African American community had experienced instances of white mob brutality, a lynching, whites-only primaries designed to minimize the black vote, legally sanctioned segregation and Ku Klux Klan intimidation. At the dawn of the civil rights era, St. Petersburg remained one of the most residentially segregated cities in the nation. Legally sanctioned segregation in neighborhoods did not end until 1968. Hospitals were segregated—whites used Mound Park (now Bayfront), and blacks used Mercy Hospital. Schools were segregated. As discussed in an earlier chapter, baseball was segregated. St. Petersburg’s famous green benches offered a place of rest, friendliness and socialization for whites, but blacks were not allowed to sit on them.

In 1953, Dr. Ralph M. Wimbish founded the Ambassadors Club for the purpose of improving living conditions, “working within the system,” primarily within the African American community. Other charter members of the club were Dr. Orion Ayer Sr., Dr. Robert J. Swain, Dr. Fred Alsup, Samuel Blossom, Sidney Campbell, George Grogan, John Hopkins, Ernest Ponder and Emanuel Stewart. Many others would become members of the club over the years. The club’s first project was to successfully integrate the Festival of the States Parade. After that, the club’s members were involved at some level in nearly all of the various efforts to eliminate segregation and discrimination within the city.

Dr. Ralph Wimbish was a leader in efforts to desegregate Spa Beach and lunch counters, obtain open accommodations for African American baseball players and integrate schools and public golf courses. Courtesy St. Petersburg Museum of History.

SPA POOL AND BEACH

Integration and extension of civil rights were slow to come in St. Petersburg and Florida. While city libraries were desegregated as early as 1952, desegregation of other facilities took much longer. The first major effort to crack segregation in our city was integration of the beaches and public pools. In St. Petersburg itself, the beaches were small areas on the bay. The major downtown beach was Spa Beach, adjacent to the Spa indoor swimming facility on the north side of the approach to the pier. Historically, this was much larger than it is today and was restricted to whites, as was the pool. In 1916, Mayor Al Lang granted blacks a small piece of beach on Tampa Bay at the South Mole, also known as Demens Landing (foot of First Avenue Southeast).

The beach area was cluttered with rubble, and bathhouse facilities were small. The site was also used for storage by the city. Even there, blacks were cautioned not to swim “in large numbers.” Blacks could not legally swim anywhere else along St. Petersburg’s forty-five miles of coastline at that time. In the 1930s, whites protested even the use of South Mole by blacks for swimming because blacks had to travel through the segregated white parts of the city to get there. Also, there were no public pools open to blacks. In 1954, Jennie Hall, a retired white schoolteacher, donated money to the city to build the first public pool for blacks. The pool was named after her and is still operating. It was recently designated a city landmark. Jennie Hall was publicly honored by the Ambassadors Club.

In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court outlawed public school segregation in the Brown v. Board of Education decision. This was an impetus to desegregate not only schools but also all public facilities. In St. Petersburg, local direct efforts to desegregate public facilities began with segregated beaches and swimming pools, not schools. In 1955, a local civil rights organization called the Civic Coordinating Committee (CCC), led by J.P. Moses, tested segregation at Spa Beach. When CCC members were denied use of the beach, Ambassadors Club member Dr. Fred Alsup filed suit against the city citing violation of their constitutional rights. The courts ruled that the segregation of the beach was unconstitutional. The city tried to undermine the court’s ruling by closing the beach anytime persons of color tried to use it and by proposing to build a cultural center or auditorium there. After a long struggle, the beach was finally opened to blacks in 1959. While some black leaders such as Reverend John Wesley Carter of Bethel Metropolitan Baptist Church led bold efforts for better treatment of blacks as early as the 1930s, it was the Civic Coordinating Committee’s efforts starting in 1955 that was the beginning of the movement to directly challenge segregation throughout the city.

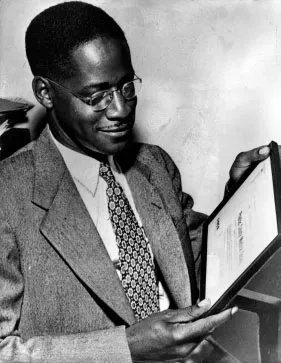

Dr. Fred Alsup, a member of the Ambassadors Club, successfully sued the city to desegregate Spa Beach and Pool. Dr. Alsup was the first African American to be admitted to the Pinellas County Medical Association. He is shown here with his medical society certificate, 1952. Courtesy St. Petersburg Museum of History.

BUSES

Integration of the city’s buses occurred in 1959, but black drivers were not hired until 1962. While the heroic Freedom Riders were treated with abuse and brutality in many areas of the South, this was not the case in St. Petersburg. On June 15, 1961, the Freedom Riders made a stop in St. Petersburg and ate at the Greyhound restaurant without incident. One white man did harass Reverend Macdonald Nelson, who was part of a welcoming committee headed by Reverend Enoch Douglas Davis of Bethel Community Baptist Church. The white harasser was arrested. At a workshop later in the day, Freedom Rider Ralph Diamond stated, “We will lose what we’ve gained if this is not followed up locally. It must get to the point where it will become a natural thing for the two races to sit together at counters.”

LUNCH COUNTERS

Actually, efforts in St. Petersburg to integrate lunch counters had begun the previous year. Local civil rights leaders including C. Bette Wimbish, Theodore Floyd, J.P. Moses, Reverend Dr. H. McDonald and others conducted sit-ins at various St. Petersburg lunch counters, including Webb’s City. In late 1960, the local National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), led by Dr. Ralph M. Wimbish, the CCC and the local chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), led by attorney Ike Williams and including Ambassadors Club member Emanuel Stewart and David Isom, began a boycott of department stores operating segregated lunch counters. This was done in coordination with a national NAACP effort. Also prominent in these efforts were Reverend Enoch Douglas Davis and the Council of Churches. (Davis was later honored for his leadership in the local civil rights movement when a community center was named for him on Eighteenth Avenue South.)

When an out-of-town Ku Klux Klan wizard tried to make trouble, he was turned away by local Police Chief E. Wilson Purdy. Chief Purdy has been credited for his professionalism in handling the boycott and related picketing. Webb’s City obtained a court injunction to stop the boycott. The injunction was quickly appealed by local NAACP lawyers Fred Minnis and Ike Williams. At the urging of Florida governor LeRoy Collins, the city established the Bi-Racial Committee to try to mediate the situation. On January 3, 1961, fifteen stores in Greater St. Petersburg, including Kress, Maas Bros., Woolworth’s and Webb’s City, dropped their segregation policies.

HOSPITALS

Historically, St. Pete had two hospitals—Mound Park, later to become Bayfront, which served whites, and Mercy Hospital built in 1923 for blacks at 1344 Twenty-Second Street South. In 1960, a city task force recommended that a new hospital for blacks be built next to Mound Park, and the city council voted to spend $1.7 million for construction. The all-white Mound Park Hospital Advisory Board opposed the construction. In response, the city council voted to build a new integrated wing at Mound Park and also renovate Mercy Hospital. Mound Park Hospital became integrated in 1961. Mercy Hospital now operates as the Johnnie Ruth Clarke Health Center and is a local landmark. Dr. Fred Alsup, a leader in the efforts to integrate Spa Beach, became the first physician to be accepted as a member of the Pinellas County Medical Society in 1962.

THEATERS

As of 1960, five of St. Petersburg’s eight movie theaters accepted black patrons on an integrated basis. The three that did not included the Center, State and Florida. On January 11, 1962, members of the NAACP Youth Council, under the leadership of Arnette Doctor, tried to buy tickets to the theaters but were denied. A few white patrons bought tickets for them, but these were not honored. A few days later, ten black young adults were arrested at the Center Theater while attempting to see the movie King of Kings, the story of Jesus. Also, NAACP president Leon Cox was fired from his job as a local college teacher, and college student Arnette Doctor had his college scholarship terminated. The NAACP Youth Council renewed picketing in 1963 under the leadership of Elnora Adams. The theaters finally agreed to desegregate in the summer of 1963.

SANITATION STRIKE OF 1968

The struggle that received the most public attention was the sanitation workers’ strike of 1968. Some might argue that this was a labor event rather than a civil rights action. But it was very much a part of the local civil rights struggle in the sense that it spoke to the fundamental issue of income inequality between whites and blacks generally. The sanitation strike of 1968 was preceded by two previous strikes, one in 1964 and one in 1966, both of which were settled within a short time. In the 1966 strike, City Manager Lynn Andrews fired 70 percent of the Sanitation Department’s workforce, but they were later reinstated. Strikers were represented by black attorneys James B. Sanderlin and Frank Peterman.

In 1968, there were several nationally significant sanitation strikes, including those in New York City, Memphis and nearby Tampa. Martin Luther King Jr., president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), was in Memphis supporting the black sanitation workers’ strike there when he was assassinated on April 4, 1968. About one month later, sanitation workers went on strike in St. Petersburg. A new pay plan had gone into effect that reduced pay for sanitation workers from $101.40 for six days’ work to $73.00 for five days’ work. This amounted to a reduction of 15 percent per hour and 28 percent per week’s pay. The new pay program was initially presented as a month-long trial, after which savings realized would be shared with the workers. This did not happen. The workers then went on strike. Local attorney Jim Sanderlin again represented the strikers. He and strike leader Joe Savage negotiated for a $0.25-per-hour increase. Andrews countered with $0.05 and offered to rescind the new pay plan and revert to the previous plan. The strikers voted to hold out for a $0.20-per-hour increase. City Manager Andrews responded by refusing to negotiate further and fired 52 workers, soon to be followed by the firing of another 150 workers.

On May 23, attorney Ike Williams, president of the NAACP, came to the support of the strikers by calling for a “selective buying” campaign—a boycott of white-owned businesses. Also, Mayor Don Jones broke ranks with the city council, criticizing the city manager and charging the city with “sowing the seeds of the present garbage crisis.” At this point, a number of fires were set, causing damage to a lumberyard, automobiles and one house—some targeting nonstrikers. Who set the fires is unknown. The strikers disavowed the fires, and Sanderlin and Savage formed an Anti-Violence Committee.

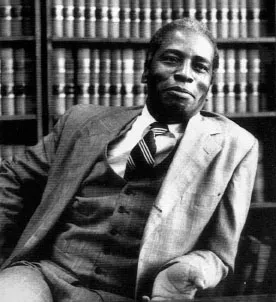

Attorney James B. Sanderlin was prominent in seeking open accommodations for black Major League Baseball players, representing city sanitation workers in the 1968 strike and in the desegregation of public schools. He later became a county and circuit court judge. Sanderlin Middle School in south St. Petersburg is named in his honor.

On June 7, the first of some forty sanitation worker marches took place starting on Twenty-Second Street near Jordan School and ending at city hall. Martin Luther King’s brother, A.D. King, agreed to support the strike and participated in a march. While the march was peaceful, it was conducted without a permit, and police arrested 43 protestors, many of whom blocked traffic. King continued to support the march, and Reverend Ralph Abernathy spoke to more than 1,000 people at Gibbs High School on July 31. On August 14, local civil rights activist Joe Waller (who later took the name Omali Yeshitela) was arrested by police for misdemeanors including simple assault on a police officer (he was later convicted). He stated that after his arrest he was subjected to police brutality, which police denied. The Times interviewed persons who stated that photographs showing injuries were circulated in the black community after his release.

Two years earlier, Waller had ripped a racially offensive painting from the walls of city hall after pleas by other black community leaders to remove it were refused. He was sentenced to three years in prison for this offense, and he had served eighteen months when Circuit Judge David Seth Walker reduced his sentence to time served in 1973. Judge Walker stated that the offense could not be excused but that he understood Waller’s indignation. Later, Judge Walker noted that a similar act committed in 2000 would likely lead to probation or the withholding of a formal finding of guilt. In 1998, the city council considered awarding Waller with a laudatory plaque as a form of apology for the pain and suffering he incurred as a result of ripping down the painting but became locked on the issue in a tie vote. Ultimately, he was granted clemency by the governor and cabinet, enabling him to have his voting rights restored.

Reverend Ralph Abernathy (left) and A.D. King (center), brother of Martin Luther King Jr., came to St. Petersburg to support the sanitation workers’ strike, 1968. Courtesy St. Petersburg Museum of History.

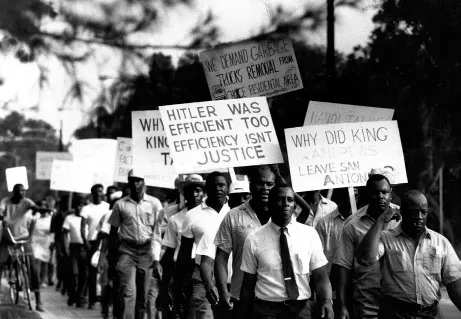

Sanitation workers march on city hall. Joseph Savage (front right) was the strike leader, and James Sanderlin (left of Savage) was attorney for the striking workers, image 1968. From Tampa Bay Times.

On August 15, 1968, the city council passed an ordinance against impeding public travel on streets and sidewalks. The strikers had begun using sidewalks for marches rather than obtaining permits for marches on the streets. On August 17, civil violence erupted in the area of the city now known as Midtown. The strike leadership denounced the violence. Some 350 National Guardsmen were activated to support local police. By the next day, there were fifty-nine arrests, eleven arsons and an estimated $120,000 in property damage. The number of arsons later rose to thirty-four, and property damage increased to between $350,000 and $400,000. Reverend Enoch Davis, writing in 1979, declared “the burnings and lootings were among the most devastating experiences ever to take place” in the city. NAACP president Ike Williams stated that the arrest of Joe Waller and the ordinances against impeding public travel, perceived as targeting the sanitation strike marches, precipitated the violence.

About two months before this civil violence, a group of “Concerned Clergy” met with the city council to try to mediate the crisis. One issue raised was offensive language still remaining in the city charter calling for residential segregation and the holding of all-white primary elections. The council agreed to rescind those provisions. Also, a few days before the violence, Mayor Don Jones initiated the Community Alliance in cooperation with the St. Petersburg Chamber of Commerce. The Community Alliance was a biracial organization whose mission was to address poor job opportunities for blacks, renovate slum housing and expand and improve educational opportunities. But these effort...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- The Making of St. Petersburg

- The Spanish Invasion at Boca Ciega Bay

- The Great Hurricanes

- Civil War in St. Pete

- Williams Park: Our Town Square

- St. Petersburg’s Piers: Anchor of the Downtown

- The Fountain of Youth Rediscovered?

- William L. Straub: Father of Our Waterfront Parks

- Birth of Our County

- World’s First Airline

- St. Petersburg’s Passion: Baseball!

- History of Our Stadiums

- Babe Ruth in St. Petersburg: A Soft Spot for Kids

- St. Pete’s First Entertainment Centers: Hard Acts to Follow

- The Grand Hotels of St. Petersburg: Mainstays of the 1920s Boom

- Civil Rights

- St. Petersburg: A Sense of Place

- Selected Bibliography

- About the Author