- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

French & Indian Wars in Maine

About this book

Covering nearly a century of conflict, this history chronicles the tragic, epic struggle for the land that would become Maine.

For eight decades, a power struggle raged across a frontier on the north Atlantic coast now known as the state of Maine. Between 1675 and 1759, British, French, and Native Americans soldiers clashed in six distinct wars to claim the strategically vital region. In French and Indian Wars in Maine, historian Michael Dekker sheds light on this dark, tragic and largely forgotten struggle that laid the foundation of Maine.

Though the showdown between France and Great Britain was international in scale, the local conflicts in Maine pitted European settlers against Native American tribes. Native and European communities from the Penobscot to the Piscataqua Rivers suffered brutal attacks. Countless men, women and children were killed, taken captive or sold into servitude. The native people of Maine were torn asunder by disease, social disintegration and political factionalism as they fought to maintain their autonomy in the face of unrelenting European pressure.

For eight decades, a power struggle raged across a frontier on the north Atlantic coast now known as the state of Maine. Between 1675 and 1759, British, French, and Native Americans soldiers clashed in six distinct wars to claim the strategically vital region. In French and Indian Wars in Maine, historian Michael Dekker sheds light on this dark, tragic and largely forgotten struggle that laid the foundation of Maine.

Though the showdown between France and Great Britain was international in scale, the local conflicts in Maine pitted European settlers against Native American tribes. Native and European communities from the Penobscot to the Piscataqua Rivers suffered brutal attacks. Countless men, women and children were killed, taken captive or sold into servitude. The native people of Maine were torn asunder by disease, social disintegration and political factionalism as they fought to maintain their autonomy in the face of unrelenting European pressure.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access French & Indian Wars in Maine by Michael Dekker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Early American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Dawnland

Maine has not always been deserving of its license plate moniker “vacationland.” Popular images of quaint harbor villages, scenic seaside vistas and quiet forests belie a dark and troubled past. For a period of nearly eighty years, between 1675 and 1759, Maine was ravaged by a series of six wars pitting fledgling colonies, European powers and indigenous people against one another. Civilians were the primary targets on both sides. Over the course of these conflicts, multiple communities were reduced to ashes or completely abandoned out of fear and the inability to defend themselves. Countless men, women and children were killed or taken into captivity to be sold into servitude or held for ransom. The dead were often stripped of their scalps, which were sold for exorbitant prices as gruesome trophies. Those left behind often found it difficult to sustain themselves over harsh Maine winters as both sides sought to destroy their enemies’ crops, livestock and property. This is the ugly history of Maine that has largely been forgotten.

Each of the six conflicts that raged across Maine during the period is referred to by its own distinct yet confusingly similar name: King Philip’s War (1675–78), King William’s War (1688–99), Queen Anne’s War (1703–13), Dummer’s War (1721–26), King George’s War (1745–49), and the French and Indian War (1755–59).1 Neatly separating, categorizing and naming these conflicts may be useful when looking through a particular historical lens, such as the conflict between European powers in North America or providing a chronological reference for specific events. However, in considering the broad history of the eastern frontier, it quickly becomes apparent that these conflicts are interrelated continuations of one another and derive their genesis from the animosity that developed between the area’s white and native populations. Although at times occurring within the broader framework of the conflict between England and France, the wars carried out on Maine soil were of a decidedly local nature. These were parallel wars waged within the greater context of imperial struggle but with distinctly local and personal goals.2

Old-world problems of political and religious conflict continued with the establishment of new-world colonies. In this new geopolitical environment, conflicts between powers in Europe spilled over to their peripheral colonies and vice versa. From the mid-seventeenth to the early nineteenth century, virtually all the European powers were embroiled in conflicts over the balance of power in Europe and overseas expansion. King William’s War inaugurated the beginning of armed hostilities between England and France in North America. Known as the Nine Years’ War in Europe, the war in Maine dragged on for a total of eleven years. Within four years of the conclusion of King William’s War, the War of Austrian Succession would engulf the Northeast in the guise of Queen Anne’s War. Thirty-two years of stasis between England and France allowed for the gradual reestablishment of English footholds on the Maine coast in the wake of Queen Anne’s War. The period was not free from war, however, as Dummer’s War erupted in the early 1720s. Unlike the past two conflicts or the wars that would follow, there was no direct intervention by the governments of England or France, and the contest was strictly limited to the native and white societies of New England. War in Europe would again bring New France and New England into armed conflict with the outbreak of the War of Austrian Succession, or King George’s War (1745–48), as the conflict would become known in New England.

Despite years of conflict between England and France in the New World, the unrelenting series of wars produced few changes in the geopolitical landscape of North America. Neither side had the strength or the will to upset the balance of power in Europe over its distant colonial holdings. Unaddressed concerns over boundary issues in North America would, however, propel England, France and, ultimately, all the major powers of Europe into yet another conflict that would have profound implications for the people of North America. The French and Indian War—or the Seven Years’ War, as it is known in Europe—was truly the first world war. By the war’s conclusion in 1763, fighting had raged across Europe, North America and the Caribbean and had reached Africa, India and the Philippines. Although the war did not materially change the political structure of Europe, the terms of the peace forced France to cede its vast North American holdings to Great Britain, forever changing the destinies of the continent’s people, European and native alike.

Europeans were not the only people caught up in the tide of geopolitical conflict during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In North America, the continent’s indigenous people engaged in their own struggle for political, economic, social and territorial equilibrium. Seeking to promote their own best interest, native societies engaged in war, trade and diplomacy with the French, the English and other native societies. The various native societies were not mere bystanders caught between two competing European powers but active participants in the struggle for North America. Significantly, the native people were forced to make these choices of war and diplomacy in the wake of drastic social change and upheaval.

During the early 1600s, native societies from the Penobscot to Cape Cod were shaken to their core by pandemic disease, intertribal warfare and ever-increasing dependence on European trade goods. Maine’s indigenous societies endured unimaginable human loss, social uncertainty and political fragmentation while contending with ever-increasing European encroachment on their homelands.

The first of the “virgin soil” epidemics appeared soon after initial contact with European traders in the mid-1500s.3 Having never previously been exposed to many of the diseases carried by European visitors, the aboriginal people were easy prey to a host of newly introduced microorganisms. The most widespread and deadly pandemic appeared in eastern Maine sometime in 1617. By 1619, it had swept through the native population of the Northeast. It is impossible to provide any firm statistics regarding its impact on the population, but it is widely believed that no less than 75 percent of the region’s inhabitants succumbed to the disease.4 In many cases, those who survived were overwhelmed by the magnitude of the calamity and unable to care for the sick and dying. The dead went unburied, and entire villages were wiped out or abandoned. Traditional rhythms of food procurement were interrupted by the ravages of the disease, causing further hardship for those who survived. Powwows, the traditional healers and spiritual leaders, were powerless in the face of the disease. Society as these people knew it was crumbling before them. In the aftermath of this crisis, the native people of Maine were forced to reassemble the pieces of their social institutions. At the same time, they would encounter continued threats to their security and independence.

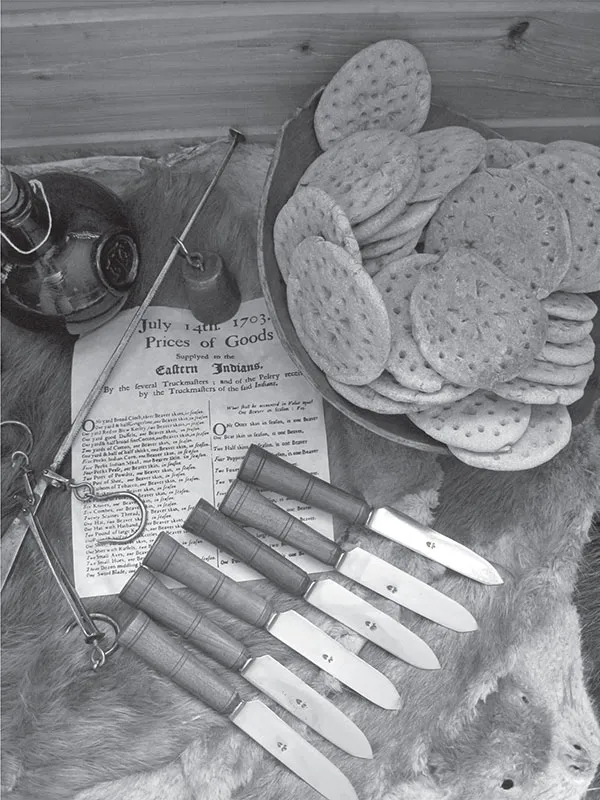

The establishment of trade with Europeans profoundly changed the native societies of Maine. Not only did it initially facilitate the spread of deadly pathogens, but the introduction of trade goods also revolutionized the material culture of the native people and the means by which they conducted their daily lives, as well as the ways in which they interacted with their environment and themselves. In the Gulf of Maine region, early trade connections were established between the native population and European explorers and fishermen. Initial contacts likely occurred no later than the early 1500s between Basque fishermen operating off Nova Scotia and the Micmac people who called the area home. In 1524, explorer Giovanni de Verrazano recorded an act of intercultural show-and-tell with Native Americans in the vicinity of Casco Bay.5 By the early 1600s, the native inhabitants of coastal Maine were in regular and routine contact with both French and English traders and fishermen. Trade provided the cornerstone of the cultural intercourse that transpired on the shores of North America. The Stone Age aboriginal inhabitants exchanged furs and feathers for kettles, textiles, knives, axes, firearms and alcohol. These items were quickly incorporated into the native people’s webs of interpersonal relationships, trade and diplomacy.

Long before the introduction of European goods in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, trade played a vital role within and between native societies. Trade and gift giving had a long-established tradition among the Algonquin-speaking people of the Northeast. It was through this mechanism, in part, that sagamores, clan leaders and heads of family bands derived the consensus on which their authority to lead rested. Diplomatic efforts between native groups were likewise facilitated by trade and gift giving, and there is evidence of extended trade networks linking distant people and cultures. Trade in this context was more important to the native people for its social, symbolic significance than its economic function. The revolution wrought by the introduction of European goods radically transformed this system of exchange into a quest for material acquisition. Furs and land became commodities to be swapped for the European goods upon which native people were becoming increasingly dependent. The transformation of a people long accustomed to being stewards of their land and its resources to increasingly desperate mortgagers of their independence was well underway by the end of the seventeenth century.

During the first half of the seventeenth century, nearly all of the Northeast’s native societies became embroiled in a series of conflicts over access to the natural resource commodities that fueled the trade in European goods. In southern New England, armed conflict would arise over access to quahog shells that were used to make wampum. In Maine and elsewhere in the Northeast, European demand for beaver pelts propelled the region into a series of conflicts that became known as the Beaver Wars. Coming on the heels of the great pandemic of 1617–19, the Beaver Wars compounded the social and political changes underway among the indigenous people of Maine. As a result of the pandemic and the Beaver Wars, the indigenous people of Maine appear to have experienced a political realignment that shaped their relationships with Europeans and each other for the next 150 years.

Trade goods. Accompanying the iron scale are typical European trade goods available through Massachusetts’s truck house system. The knives and biscuit are representative of what native people could have traded for one beaver skin, on top of which they are displayed. Courtesy of Ken Hamilton.

Considerable ambiguity exists regarding the ethnic, social and political distinctions of the Northeast’s indigenous people. Despite differences among the people of the region, they all shared a similar Algonquin religious and linguistic heritage. They also shared similar ideas of social and political order in which the mantle of leadership was gained through popular consent rather than coercion or unquestioned obedience. The most fundamental unit of social order and polity lay in the kinship band. These kinship bands were free to associate themselves with those leaders whom they felt could best represent their interest and provide for their needs. Kinship bands sharing similar interests and needs would coalesce into a sort of clan structure, and clans would come together to form the basis of what is thought of as the tribe. Although political authority was not derived from familial lineage, leaders often emerged from large and influential families. While the institution of the kinship band survived, there appears to have been a political reorganization of the tribes in the wake of war and disease.

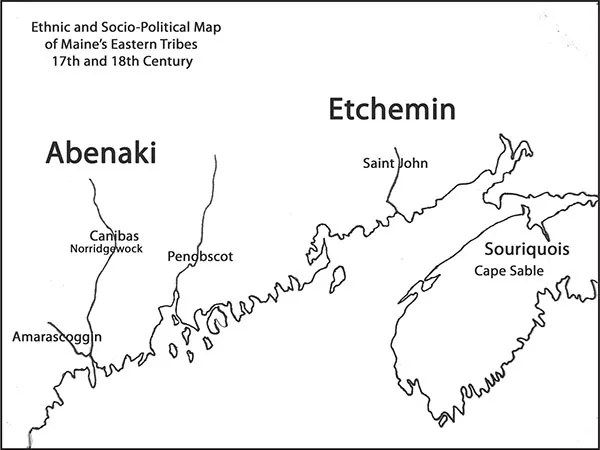

Early European chroniclers of Maine, both French and English, described several strong tribal leaders who appeared to have been vested with centralized tribal authority. French records identified three sociopolitical groups in the Gulf of Maine region.6 Inhabiting Nova Scotia and New Brunswick to the St. John River was a people identified as the Souriquois. To the west of the Souriquois, the Etchemin occupied the lands between the St. John and Kennebec Rivers, while the Almouchiquois lay claim to the lands south and west of the Kennebec. Although early English observers seem to be slightly more nuanced in their assessment of the ethnic identities of Maine’s native population, they fundamentally support the idea of a small number of strong native political entities along the Maine coast. By the second half of the seventeenth century, however, it appears that the eastern tribes had become politically fragmented, with a host of leaders claiming to represent disparate kinship bands.

By the beginning of the eighteenth century, the government of Massachusetts, which was responsible for the administration of Maine, consistently used appellations for native societies based on their place of residence. Although probably imprecise, the nomenclature used by Massachusetts provides broad insight into how the native societies of Maine arranged themselves politically. The Eastern Tribes, as recognized by Massachusetts, consisted of the Cape Sable, St. John, Penobscot, Kennebec, Amarascoggin7 and Piqwacket Indians. Residing in Nova Scotia and portions of New Brunswick, the Cape Sable Indians were undoubtedly the same people earlier identified as the Souriquois and would later be known as the Micmac. Centered in the St. John River area of eastern Maine and western New Brunswick, the St. John Indians would today be identified as the Passamaquoddy and Malicites and could trace their ethnic identity back to the Etchemin identified by the French. The Penobscot who occupied the land from roughly Mount Desert Island to the St. George River are harder to identify ethnically. While they retained close relations with the St. John people to their east and are often classified in period documents as Tarrentine, they are at other times recognized as eastern Abenaki.8 To the west of the Penobscot people, the Kennebec or Canibas Indians of the Kennebec River area were at times referred to as Norridgewock Indians in the correspondence of Massachusetts officials. The Kennebec or Norridgewock Indians were Abenaki in ethnic composition and closely related to the Amarascoggin and Piqwacket to their west. Living along the Androscoggin and Saco Rivers, respectively, the Amarascoggin and Piqwacket peoples represented the other Abenaki people of Maine.

Although Massachusetts clearly identified six eastern tribes, in looking at the records of negotiations and treaties, it is readily apparent that by the eighteenth century, none of the tribes possessed any sort of centralized authority. Multiple members of a single tribe invariably affixed their names or totems to a single document, and Massachusetts negotiators regularly made inquiries as to whether representatives were able to speak on behalf of other tribal factions in their absence. An example of the diplomatic difficulties created by the eastern tribes’ political factionalism can be seen in an early effort to bring King William’s War in Maine to an end. In August 1693, a peace treaty was signed at Pemaquid between Massachusetts and the eastern Indians. Thirteen sagamores representing the Kennebec and Penobscot signed the treaty.9 Despite this seemingly broad representation, the treaty proved unsatisfactory to native people as a whole, and internal divisions over the sale of land to the English by Madockawando, one of the Penobscot representatives, led to the rejection of the treaty and six more years of war. Diplomacy between Massachusetts and the eastern tribes would continue to be plagued by the native people’s political fragmentation and difficulty achieving consensus. Recurrent instances of splintered and partial commitments from portions of the eastern tribes led Massachusetts to believe that the native people of Maine consistently acted with perfidy and ill faith. Ultimately, this factionalism prevented the native people from effectively advocating for themselves in the face of increasing tension with their English neighbors.

Author’s map.

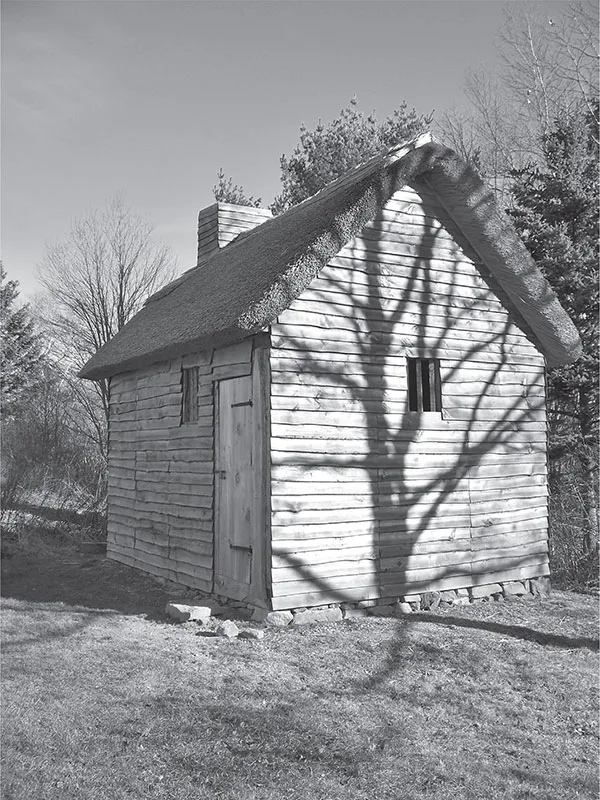

What began as an essentially harmonious relationship between the native people of Maine and European visitors gradually soured as those Europeans made permanent inroads on North America. During the early 1600s, seasonal fishing stations and temporary fur trading outposts began to appear on the rocky shores and navigable rivers of midcoast Maine. Monhegan, Damariscove, Cape Newagen and Pemaquid all served as important temporary fishing outposts for English fishing ventures.

Transient fur trading operations were established by the English at Cushnoc in what is now Augusta and at Pejeepscot, where the Androscoggin and Kennebec Rivers meet to form Merrymeeting Bay. Both the French and the English attempted to establish permanent settlements on the Gulf of Maine between 1604 and 1613. At the mouth of the Kennebec River in present Phippsburg, John Popham and his associates attempted to establish the first permanent English settlement in 1607. The project ultimately failed, but it was a portent of English intentions to settle the region. French endeavors to launch settlements at the mouth of the St. Croix River in 1604 and Mount Desert Island in 1613 likewise failed, but failure was only temporary. By the late 1620s, the English had established themselves at Pemaquid, and by 1635, the French were entrenched at Pentagoet in today’s Castine. By 1675, English communities dotted the coast of Maine from the Piscataqua to the Damariscotta River. Increased European presence in the former homelands of Maine’s native people ultimately led to misunderstanding and increased tension, eventually resulting in eighty years of war.

Pemaquid fisherman’s house. This reconstructed seventeenth-century building typifies the type of dwelling found at the early Pemaquid fishing station. Fishing stations such as this one dotted the midcoast region at Monhegan, Damariscove and Cape Newagen. Seasonal and later permanent fishing stations helped fuel white settlement of the midcoast region. Author’s photo.

The issues dividing the native and European people of Maine arose from five basic and often intertwined points of contention. Divergent notions of land, trade, language, sovereignty and justice all contributed to the misunderstanding and mistrust that characterized native and European relations during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The sale, ownership and use of land became increasingly problematic as English settlers permanently established themselves and sought to acquire more land for their rapidly expanding population. The growing dependency of the indigenous people on European trade goods and the resulting interactions between societies periodically engendered frustration and desperation among Maine’s native people and helped fuel land controversy. Misunderstandings in the application of language and covenants led to divergent views regarding transactions and agreements, which often resulted in failed expectations for both sides. English views of native polity and sovereignty also undermined hopes for stability and peaceful coexistence in the province of Maine.10 Finally, native inability to achieve satisfactory justice through the English legal system wrought frustration and suspicion between the two cultures.

Astonishing growth of the white...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- 1. Dawnland

- 2. Two Kings

- 3. Missions and Mourning

- 4. Bringing It Home

- 5. Fear and Fatigue

- 6. Justice

- 7. Parallels

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Author