- 131 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Battle of First Deep Bottom

About this book

This Civil War history examines a complex and pivotal, yet often-overlooked, battle of the Petersburg Campaign.

On July 26, 1864, Union general Winfield Scott Hancock's corps and three cavalry divisions under Philip H. Sheridan crossed to the north side of the James River at the Deep Bottom bridgehead. What was supposed to be a raid on Confederate railroads and possibly even a breakthrough to the Confederate capital of Richmond turned into a bloody skirmish.

Richard H. Anderson's Confederate forces prevented a Union victory, but only at a great cost. In response, Robert E. Lee was forced to move half his army from the key fortifications at Petersburg, which were left all the more vulnerable in the subsequent Battle of the Crater.

Historian James S. Price presents an authoritative chronicle of this pivotal moment in the Petersburg Campaign and the close of the war. Including newly constructed maps from Steven Stanley and a foreword from fellow Civil War scholar Hampton Newsome, this is the definitive account of the Battle of First Deep Bottom.

On July 26, 1864, Union general Winfield Scott Hancock's corps and three cavalry divisions under Philip H. Sheridan crossed to the north side of the James River at the Deep Bottom bridgehead. What was supposed to be a raid on Confederate railroads and possibly even a breakthrough to the Confederate capital of Richmond turned into a bloody skirmish.

Richard H. Anderson's Confederate forces prevented a Union victory, but only at a great cost. In response, Robert E. Lee was forced to move half his army from the key fortifications at Petersburg, which were left all the more vulnerable in the subsequent Battle of the Crater.

Historian James S. Price presents an authoritative chronicle of this pivotal moment in the Petersburg Campaign and the close of the war. Including newly constructed maps from Steven Stanley and a foreword from fellow Civil War scholar Hampton Newsome, this is the definitive account of the Battle of First Deep Bottom.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Battle of First Deep Bottom by James S Price in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

THE PROGRESS OF OUR ARMS

“CHEW AND CHOKE AS MUCH AS POSSIBLE”

It had been a summer drenched in blood.

While the trees and flowers were in vernal bloom, the expectations of thousands had also blossomed afresh in the hopes that the coming campaign season of 1864 would hammer the final nail in the coffin of the rebellion. As spring turned to summer, these hopes were dashed as the numbers of dead and maimed escalated with no clear end in sight.

On March 12, 1864, freshly minted Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant was given supreme command of the armies of the United States. Grant came from the Western Theater of operations, where he had seen wild success at places like Vicksburg and Chattanooga. He came east, where the Union cause had not fared so well, and quickly put into motion a plan that called for a concerted drive that spanned the entire chessboard of war. Back west, William Tecumseh Sherman would strike from Chattanooga into northern Georgia, while Major General Nathaniel P. Banks assailed Mobile, Alabama. In the east, Major General Benjamin “Beast” Butler would lead his Army of the James against Richmond from the southern approaches, while Union troops under Major General Franz Sigel went after valuable supply lines and bases in southwestern Virginia. Grant saved the biggest prize for himself and decided to make his camp with the Army of the Potomac—the tenacious (if unlucky) army that had been bedeviled by Robert E. Lee for nearly two years. In the waning days of April, they would set out to bag the wily Gray Fox and eradicate his formidable Army of Northern Virginia for good.

While Grant’s conception for a simultaneous push against Confederate manpower and resources was sound, it looked as if his carefully orchestrated offensive would unravel before the month of May had concluded. At that time, Butler’s men were stalemated at Bermuda Hundred, and Sigel’s valley army had suffered a humiliating defeat at New Market. Farther west, things were looking just as gloomy. The Army of the Tennessee was defeated at New Hope Church on May 25, and Nathaniel P. Banks—a politician turned soldier who was notorious for being soundly beaten in most of his martial endeavors—completely botched the attempt to take Mobile in what Sherman famously remarked was “one damned blunder from beginning to end.” There would be far more blundering before all was said and done.

As galling as these fiascos were, it was Grant himself who was in store for the rudest awakening of them all. Grant led his “Army Group” consisting of Major General George Gordon Meade’s Army of the Potomac and Major General Ambrose E. Burnside’s independent IX Corps as they crossed Virginia’s Rapidan River west of Fredericksburg to entice Lee into open battle. In order to do this, however, Grant had to pass through a tangled wasteland known locally as the Wilderness. The Federals were still negotiating the dense underbrush of this thicket when Lee and his grizzled veterans showed up to give battle. The resulting Battle of the Wilderness raged May 5–6 and provided a severe shock to Grant, whose troops suffered about 20,000 casualties, compared to Lee’s 11,000. Old Marse Robert had scored yet another tactical victory, but his opponent showed his mettle when, instead of pulling back to lick his wounds and refit for the next big bloodletting, Grant disengaged from the Wilderness and continued to press on—this time toward the small hamlet of Spotsylvania Court House. The two armies battered each other May 8–19 in some of the most brutal and horrific fighting the war had yet seen. Grant, who had clearly underestimated Lee, lost a staggering 18,000 men, while his opponent lost 9,500 irreplaceable fighters.

Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant near Cold Harbor, June 1864. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

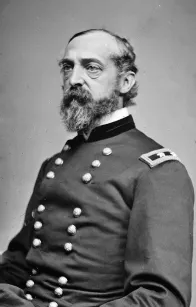

Major General George G. Meade led the Army of the Potomac. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Stride after agonizing stride, inch by bloody inch, Grant’s battered host was marching its way ever closer to the Confederate capital and whittling down Lee’s vaunted army in the process. As the inexorable march continued to the North Anna River and across the Pamunkey, an ailing Lee found himself unable to wrest the strategic initiative from his opponent’s hands. Confederate hopes were momentarily resurrected when the Rebels scored a costly defeat on Grant’s army at Cold Harbor, just northeast of Richmond. After the now infamous assault on the morning of June 3, the two sides became stalemated yet again. The Cold Harbor Campaign produced 13,000 dead and wounded Federals, while the Army of Northern Virginia lost about 2,500 men. Grant hunkered down June 4–12, consolidated his lines and began to scheme his way out of the deadlock.

With Lee’s army and the Chickahominy River interposed between Grant and Richmond, the cigar-smoking chieftain turned his gaze south, toward the city of Petersburg. Five major railways funneled into Petersburg—vital lines coming in from the Shenandoah Valley, southeastern Virginia, and railways connected to blockade-running ports, all of which connected to Richmond. In addition to the railways, Petersburg’s road network also supplied the Confederate capital, and important lead works that manufactured the deadly missiles used by Lee’s army made for a tempting target.

As Petersburg went, so went Richmond. Thus, on June 6, 1864, Grant informed Benjamin Butler that he was planning on shifting the Army of the Potomac away from Richmond and toward Petersburg. Butler’s Army of the James had been “bottled up” at Bermuda Hundred, a peninsula situated squarely between Richmond and Petersburg, and his engineers had maps that the Army of the Potomac would need to get across the James River. Butler assisted Grant in getting the information he needed and also decided that he would take a gander at seizing Petersburg himself. Thinking that the “Cockade City’s” defenses had been weakened by troops being shifted north to Lee’s army, Butler sent four brigades of infantry to take the city. In what lives on in local legend as the “Battle of Old Men and Young Boys,” a ragtag group of local defense troops and citizens led by former governor of Virginia Henry A. Wise was able to confound the confused and timid Union advance.

The Army of the Potomac fared no better. When Grant slipped away from the killing fields of Cold Harbor, he attempted to take Petersburg starting on June 15—three days later, Lee’s men began to arrive, and any opportunity to waltz into Petersburg completely evaporated.

With the Army of Northern Virginia entrenching, “storming Gibraltar would be as easy” as taking Petersburg. That being said, the Confederacy’s premier army was in a bad way, and reverting to trench warfare was not an ideal outcome for an army that was suffering a shortage of every resource imaginable. Lee acknowledged as much when he told Jubal Early, “We must destroy this Army of Grant’s before he gets to the James River. If he gets there it will become a siege and then it will be a mere question of time.”1

Both sides were eager to break the deadlock. When the campaign dissolved into siege operations and the summer heat turned the trenches into cesspools of filth and suffering, Grant was offered a pertinent bit of advice: “Hold on with a bulldog grip, and chew and choke as much as possible.”2

“AN UNCONDITIONAL SURRENDER”

The man who had given Grant that advice, President Abraham Lincoln, was given plenty of opportunities to heed his own counsel in the spring and summer of 1864. While Father Abraham was not shouldering a musket or directing artillery fire, he was certainly embroiled in conflict aplenty: conflict in his family, his inner circle, with antiwar Democrats (known as “Copperheads”) and even with members of his own party. And if this wasn’t enough to drive any man to distraction, Lincoln was also facing reelection and had to wage a campaign to convince the American people to keep him in office come November. Lincoln was waging a war while campaigning to make sure that he could keep prosecuting that very same war—at least in the way he saw fit.

“It is a pertinent question often asked in the mind privately, and from one to the other, when is the war to end?” he told a Philadelphia audience on June 16, 1864. “Surely I feel as deep…an interest in this question as any other can, but I do not wish to name a day, or month, or a year when it is to end…We accepted this war for an object, a worthy object, and the war will end when that object is attained. Under God, I hope it never will until that time.” This last sentence was potentially controversial, since it implied more blood and treasure to be sacrificed on the altar of the nation. Thus, Lincoln added some rousing encouragement: “Speaking of the present campaign, General Grant is reported to have said, ‘I am going through on this line if it takes all summer.’” The Philadelphians in the audience burst forth in cheers and applause, but what would the rest of the country say at this prospect?3

With Union military efforts bogging down or resulting in outright failure, Lincoln became unsettled about his prospects for winning a second term. All he had to do was harken back to the midterm elections of 1862, when the rising death toll, new taxes, the suspension of habeas corpus, the draft law and—worst of all in the minds of many voters—the announcement of the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation resulted in the Republican Party losing 122 seats in the House of Representatives. Two years later, many of those same issues were still raw with the American people, and when it became increasingly evident that the Democrats were going to nominate the ever-popular Major General George B. McClellan as their presidential candidate, there was genuine cause for concern.

Officially, Lincoln was the nominee for the National Union Party, whose platform included, among other planks, a vow “not to compromise with the Rebels, or to offer them any terms of peace except such as may be based upon an unconditional surrender”—a far cry from Democrats’ desire for an “honorable peace” that would leave the fate of the slaves in the South ambiguous to say the least.4

Even so, Lincoln was not blind to the fact that a peace agreement could theoretically be worked out before Americans went to the polls. Negotiations would have to be handled ever so delicately, but July 1864 saw two different gestures of peace with the Confederate government. The first took place outside American or Confederate soil, across Niagara Falls in Canada. There, the famous founder and editor of the New York Tribune, Horace Greeley, found himself in over his head in dealing with two Confederate negotiators who had no authority to offer any official terms backed by Jefferson Davis’s administration. This debacle ended with Greeley feeling duped and humiliated and peace as unreachable as ever.

The second notable peace arbitration took place in Richmond itself, where Colonel James F. Jaquess and James R. Gilmore crossed into the Confederate capital via—of all places—Deep Bottom to discuss peace directly with Jefferson Davis himself. When the Southern head of state drove home the point that there could only be peace if the Confederate States of America was allowed its independence, the handwriting was on the wall, since the Lincoln administration would never accept such an outcome. “Any proposition,” the Rail Splitter wrote to the Confederates, “which embraces the restoration of peace, the integrity of the whole Union, and the abandonment of the slavery…will be received and considered by the Executive government of the United States.” Any peace proposal lacking those key components would not be contemplated. With the July peace ovations dead on arrival, the North would have to win its victory on the field of battle.5

Chapter 2

THE OPPOSING FORCES

“THE ARMY WAS TERRIBLY SHATTERED”

By the spring of 1864, the Army of the Potomac had garnered a reputation for being tough, implacable and steadfast in the face of appalling conditions (to say nothing of appalling leadership). As the war entered its third year, some remarked that the army’s personality reflected that of a bulldog—as one of its members observed, “You can whip them time and again, but the next fight they go into, they are in good spirits, and as full of pluck as ever.” But as every dog owner can attest, a mutt can be abused and ill treated to the point that it will cower at its own shadow. The meat grinder of the Overland Campaign had begun to produce such a result in these resolute defenders of the republic.6 Consider the agonizing reflections of a survivor:

The army was terribly shattered. It had lost considerably more than half of the troops that crossed the Rapidan on the 3d of May. It had accomplished nothing, save that it had killed, wounded, and captured some 30,000 men of Lee’s army. It had carried out its policy of attrition and that was all. It had simply depleted Lee’s army. It had neither disintegrated nor demoralized it…The campaign must be pronounced a failure. Of this there can be no real question…The result of this campaign was to reduce our army in numbers and morale out of all proportion with its adversary.7

No group of soldiers embodies the angst of this quote more than the steadfast II Corps, which would be tasked with menacing the capital of the Confederacy during the First Battle of Deep Bottom. One chronicler of the war went so far as to say that “the history of the Second Corps was identical with that of the Army of the Potomac.” From Seven Pines to the Bloody Lane of Antietam, Marye’s Heights at Fredericksburg to the repulse of Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg, the Clover Leafs had earned a solid reputation as the army’s toughest fighters. Whenever a situation was particularly dire, the II Corps, led into battle by its redoubtable commander, Winfield Scott Hancock, would be called on to win the day. Sadly, this reputation would carry over into 1864 with disastrous consequences.8

“PLAYED OUT!”

The troubles began on the first day of the Battle of the Wilderness. On May 5, 1864, the men of the II Corps experienced something they were not entirely used to: being pushed back. Fighting in the underbrush led to confusion, demoralization and outright panic in some instances. The nightmarish landscape, littered with casualties, took on an added element of hellishness when the woods caught fire, and the men were forced to watch their wounded comrades incinerated before their very eyes. The second day of the battle went no better, and the tone was set for a campaign that was simply more difficult than any other that the boys could recall. The corps would see action throughout the Spotsylvania Campaign, most notably at the “Mule Shoe” on May 12 and the Harris Farm on May 19. Despite the heavy combat that the corps was enduring, morale remained high as the campaign sputtered toward Richmond. All of that changed at Cold Harbor.

Following the fighting along the North Anna River, the II Corps was forced to endure an agonizing night march on the evening of June 1–2 that exacerbated the men’s growing sense of frustration and fatigue. To make matters worse, a guide who was sent to lead the corps to its position on the Union left flank got lost, so that by the time they arrived in their sector of the Union lines, Hancock’s men were simply played out. Because o...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface. “Who Will Write Up the Deep Bottom Fights?”

- Chapter 1. The Progress of Our Arms

- Chapter 2. The Opposing Forces

- Chapter 3. The Bridgehead Is Established

- Chapter 4. Clash at Tilghman’s Gate

- Chapter 5. Confidence Lost

- Chapter 6. Collision at the Darby Farm

- Chapter 7. Time Slips Away

- Chapter 8. July 29, 1864

- Chapter 9. Closing Scenes

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Author