- 302 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

One of the oldest cities in Texas, Galveston has witnessed more than its share of tragedies. Devastating hurricanes, yellow fever epidemics, fires, a major Civil War battle and more cast a dark shroud on the city's legacy. Ghostly tales creep throughout the history of famous tourist attractions and historical homes. The altruistic spirit of a schoolteacher who heroically pulled victims from the floodwaters during the great hurricane of 1900 roams the Strand. The ghosts of Civil War soldiers march up and down the stairs at night and pace in front of the antebellum Rogers Building. The spirit of an unlucky man decapitated by an oncoming train haunts the railroad museum, moving objects and crying in the night. Kathleen Shanahan Maca explores these and other haunted tales from the Oleander City.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Galveston and the Civil War by James M Schmidt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Bondage

NEGROES—Have now 25 on hand and a portion choice No. 1 negroes. Field hands and house servants…The negroes are all sent out of town every night and exhibited next day before our door. We sell at auction or private sale as may be for the interest of our friends.

—J.S. & J.B. SYDNOR

Galveston Daily News, November 20, 1860

This Galveston is getting to be a notorious place,” George Fellows wrote his friend Jesse Sawyer, a fellow abolitionist, in October 1844. Sometime before, Fellows had witnessed the Reverend James Huckins—minister of the island’s First Baptist Church, of which Fellows was a founding member—beating his female slave. Fellows confided to Sawyer that he could no longer go to the church, as he could not “listen to preaching, with profit, where the remembrances of the sound of the sighs and groans of the slave of Mr. Huckins will ring in my ears.” He added:

Yesterday I was called upon by Mr. Huckins to answer in regard to some remarks of mine in regard to his whipping his woman slave and whether I had practiced [and] intended to continue to inquire of a servant when they came where I was…and whether I thought it right to listen and believe what servants said. I told him that servants were to be believed sometimes as well as white folk.

Sometimes, dear brother, I wish you were here to preach us plainly the way of life on Salvation. But, Dear Brother, if like me you should yield to nature’s feelings in burst of indignation at the recital of cruelty and oppression because man does not love his brother as himself…in this land of vice and Sabbath breaking [it] would ruin your influence as a minister forever. Though here the life of a minister of Christ is consistent if he does not get drunk and whip his slave too much; he can preach the truth plainly without fear if he does not touch slavery. As a private or public subject that must not be touched in any form.

To give an idea of these people: Mr. Andrews, a lawyer, who had resided at Houston several years by the influence of Mr. Eliot, the British Minister to the Texas Republic, came to this place to hold a discussion on the subject of slavery. But he was placed in a boat and conveyed to the mainland to hunt for himself. Another man, still a slaveholder, was threatened with the same fate if he opened his mouth on the subject. So you can perceive the utter dislike of these people to hear anything on the subject.

A short time ago a mob took a Negro from jail by force and hung him because some of the other citizens wanted him to have a fair trial by the course of law, but was hung by them ten hours after taken. Though a very bad Negro, yet I doubt whether he intended the crime for which he was hung.

Dear Brother…Have wished you here many a time to labor to build up, if twas the Lord’s will, our little Baptist Church (though I am not a member and don’t expect to be while Mr. Huckins is here as minister or teacher). You could do but little good now as he has old enmity against you. He would wish to domineer and control you or else spoil your influence by charging you of being, or having been, an Abolitionist, which would injure your influence and happiness. Though you might catch him pursuing his slave with a badger club or big stick, yet this, a slave holding world, would approve because the law did, and condemn you as a suspected Abolitionist.

May Heaven direct you, and if we should meet on Earth no more, may we meet where Slavery, Sin, Sorrow and Death are known and felt no more.1

In a single letter, George Fellows managed to touch on a number of points related to slavery in antebellum Galveston: the treatment of slaves, divisions in the churches, the behavior of masters, jurisprudence, the hard opinions against abolitionists and more. Some historians’ claims that “slaves had never been a major factor in Galveston’s economy so the issue of slavery was more emotional than real” or that slaves “loved the Island life and were always loathe to leave it” bely the facts: the island was a busy center of the illicit foreign slave trade, had a slave population whose growth outpaced that of its free population, was home to the largest slave market west of New Orleans and was witness to all the cruelties that attended the institution. It was also the single most important reason that Galvestonians would vote overwhelmingly to leave the Union.2

FREEBOOTERS AND SMUGGLERS

Slavery in Galveston can be traced back to the first permanent settlements on the island in the early 1800s by privateer Louis-Michel Aury and the Lafitte pirate family. Aury, born in France, established a base in Galveston in September 1816 under the auspices of the nascent Republic of Mexico. The settlement—which quickly attracted hundreds of recruits—was intended to serve as a base of operations against Spanish interests in Mexico and on the high seas. Aury had previously perfected his slave-smuggling practice in Spanish Florida; within a year of settling in Galveston, his crews took more than six hundred Africans from captured ships. Aury’s men built barracks to house their human “prizes” until they could be smuggled into Louisiana and sold into slavery.

Aury abandoned Galveston in 1817 and returned to Florida; into the brief vacuum of power stepped the pirates Antoine, Pierre and Jean Lafitte, who would establish a highly successful slave-smuggling operation on the island. Details of their early years—even their places of birth—are scant, but by the early 1800s, the brothers were using Barataria Bay and New Orleans as a base for their wine import and blacksmith businesses. These legitimate enterprises were only a front for their empire in brokering the sale of smuggled and captured goods. They used the profits from the smuggling operations to outfit their own ships and—recognizing the still greater profits to be reaped—they engaged in the illegal slave trade.

The Lafittes transferred their operation to Galveston in early 1817 to avoid the increasing enforcement of United States laws against the illegal slave trade. Their operation consisted of slave barracks, hundreds of traffickers in their employ, a mansion and a tavern to entertain the pirates when they were not at sea chasing and capturing slave ships. Within months, the United States consul in Galveston reported that “pirate boats are very numerous and commit their depredations without respect to flag or nation to smuggle slaves into Louisiana from Galveston.” Likewise, Beverly Chew—collector of customs at New Orleans—reported “the most shameful violations of the slave act…[are] practiced by a motley mixture of freebooters and smugglers established at Galveston.”3

Among Jean Lafitte’s accomplices in the illicit slave trade was James Bowie, the Texas folk hero made famous for his invention of the eponymous “Bowie knife” and his death in the Battle of the Alamo. Bowie made his early fortune in land speculation and used those profits—in the words of his brother, John—“in speculating in the purchase of Africans from the notorious Lafitte, who brought them to Galveston, Texas, for sale.” John explained the scheme in which the Bowie brothers took part and which netted them $65,000:

We first purchased forty negroes from Lafitte at the rate of one dollar per pound, or an average of $140 for each negro; we brought them into the limits of the United States, delivered them to the custom-house officer, and became the informers ourselves; the law gave the informer half of the value of the negroes, which were put up and sold by the United States marshal, and we became the purchasers of the negroes, took the half as our reward for informing, and obtained the marshal’s sale for the forty negroes, which entitled us to sell them within the United States.4

Lafitte was pushed off of Galveston in 1821, but the island remained a hub of illegal slave trading for years. Indeed, as late as 1859, the secretary of the treasury was compelled to send the revenue cutter Harriet Lane to Galveston to combat the trade that still existed in the Gulf of Mexico. (Ironically, the Harriet Lane would play a prominent role in the Battle of Galveston only a few years later).

Just as the pirates were being pushed out of Galveston, Americans began to colonize then-Spanish Texas on authorization of a grant given to Moses Austin and—upon his death—his son, Stephen F. Austin, the “Father of Texas.” Immigration into Texas increased when Mexico secured its independence from Spain in 1821, and many settlers brought their slaves with them. However, Mexico had laws against slavery, and the increased settlement of Texas seemed in peril if owners could not be certain that their human “property” would be secure. Austin insisted that “Texas must be a slave country,” and once the republic earned its independence in the Texas Revolution, slavery would have a firm and—owing to its constitution—legal foothold.5

THIRTY-NINE LASHES

Just as Galveston grew quickly from its start of a handful of homes and residents after the Texas Revolution, so too did slavery grow on the island. A state census in 1847 showed Galveston with a population of 4,758; by the first full federal census in 1850, Galveston’s population stood at 4,177 but grew to 7,307 in 1860. Of those numbers, the slave population grew from 283 in 1847 to 678 in 1850 and to 1,178 in 1860, a four-fold increase compared to a two-fold increase in Galveston’s free population. Only two “free” African Americans were recorded in Galveston in 1860 (down from 30 in 1850), almost certainly owing to an 1858 state law that required freed blacks to leave Texas, select a master or be arrested and sold into slavery.6

Many—if not most—of the slaves in Galveston came with their owners when they moved to the island, but there was no shortage of slaves available through the legal domestic slave trade, and Galveston would become home to the largest slave market west of New Orleans. A number of merchants regularly bought and sold slaves on the streets and in the auction houses of Galveston, including J. Castanie & Co., T.H. McMahan & Gilbert, John O. & H.M. Trueheart and Colonel John S. Sydnor (who operated the city’s largest slave market). The firms advertised in Galveston newspapers offering slaves for sale; typical was an ad by the firm of McMurry & Winstead: “30 more choice Carolina and Virginia Negroes just arrived and for sale at our Slave Depot, Leonard Building, Church Street. Persons coming to this market to buy Negroes, will always find a good assortment at our house, as we are receiving fresh lots every month.”7

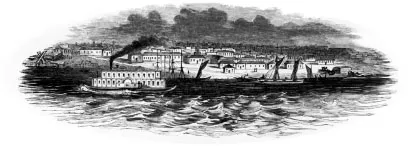

1845 woodcut engraving of the Port of Galveston. Library of Congress.

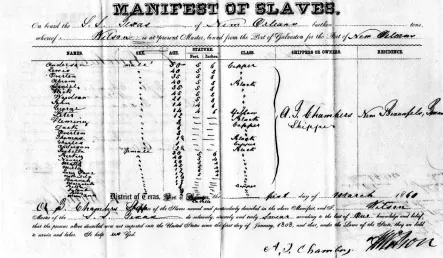

Manifest of slaves being transported on the SS Texas from Galveston to New Orleans in 1860. National Archives.

Once sold or hired out in Galveston, slaves could find themselves in a number of situations. Galveston was unique in that it encompassed domestic and trade labor in the city, plantation labor on outlying areas of the island and maritime labor in the port. Male slaves could be found in factories, foundries and cotton presses; they were blacksmiths, barbers and carpenters; they shelled streets, built railroads and harvested crops. Female slaves generally worked in homes; they were also employed as prostitutes in the city’s “houses of ill fame.”

Of special interest is the intersection of slavery with Galveston’s maritime economy. In addition to the domestic, factory and plantation labor mentioned above, Galveston slaves also performed a variety of jobs on the waterfront: as crew on barges carrying cargo and passengers to and from the wharves and ships, driving wagons from the wharf to warehouses in the city and loading and unloading the holds of ships. Masters sometimes hired out their slaves as crew on the steamers that plied the coast or traveled inland on the bayous. The bustling seaport also posed risks for slave owners as the ships offered a tempting means for the slaves to escape. To that end, Galveston employed a permanent inspector to “thoroughly search for any slave or slaves who may be secreted” aboard outgoing ships.8

Of the slaves in Galveston, one antebellum visitor declared that he feared their “leisure moments are few and his lashes frequent.” One needs to look no further than state law and municipal ordinances to see that this was so. Slaves were proscribed from hiring their own time; slaves found “beyond and away from the premises of their owner…without written permission” were subject to whipping; slaves were prohibited from owning firearms; a slave found gambling could be fined or given “thirty-nine lashes on his…bare back”; and disorderly conduct and “efforts to strike any white person” also carried the penalty of thirty-nine lashes.9

Famed journalist Frederick Olmsted wrote of antebellum Galveston’s “devotion of its inhabitants to African slavery as the social ideal.” It’s no surprise then that Texans who abhorred slavery—such as George Fellows—were hardly welcome in Galveston. As the Galveston Weekly News declared in 1857, “Those who are not for us must be against us. There can be no middle ground. Those who denounce slavery as an evil, in any sense, are the enemies of the South.” For Galvestonians, the great question of who was “for” and who was “agin’” would soon be put to a vote.10

EPITAPH OF THE UNION

One historian declared that “the emotional and purely political factors pushing Texas toward secession…may have been in the making for twenty years.” Indeed, as early as 1839, Theodore Frederic Gaillardet—an early writer and traveler in Texas who communicated his favorable impressions of the territory to his native Europe—anticipated the secession crisis. He wrote that the “germ of Texas’ future greatness” was in its position as a destination for slaveholding planters from throughout the South, adding:

It will become in the more or less distant future, the land of refuge for the American slaveholders; it will be the ally, the reserve force upon which they will rest…If…that great association, the American Union, should one day be torn apart, Texas unquestionably would be in the forefront of the new confederacy, which would be formed by the Southern states from the debris of the old Union.11

The state gubernatorial election of 1859 pit Sam Houston against the incumbent Hardin R. Runnels (they had run against each other in 1857); although both men supported slavery, Houston was a Unionist, while Runnels was thought “safe” on the issue of states’ rights and—unlike Houston—supported reopening the African slave trade. Houston won, but sectional matters came to a head in the presidential election of 1860; Galvestonians overwhelmingly voted for the Southern Democrat John C. Breckenridge over rivals John Bell and Stephen Douglas (Republican Abraham Lincoln was not on the ballot in Texas). Breckenr...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- 1. Bondage

- 2. War!

- 3. Stranglehold

- 4. Occupied

- 5. Battle

- 6. Mercy

- 7. Dissent

- 8. Entrenched

- 9. Cat-and-Mouse

- 10. Fever

- 11. Liberation

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Author