- 161 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Learn more about a key military bastion of the American Revolution and guard of the Western frontier, Pittsburgh, through this illustrated history.

For nearly half a century, Fort Pitt stood at the forks of the great Ohio River. A keystone to British domination in the territory during the French and Indian War and Pontiac's Rebellion, it was the most technologically advanced fortification in the Western Hemisphere. Early Patriots later seized the fort, and it became a rallying point for the fledgling Revolution. Guarding the young settlement of Pittsburgh, Fort Pitt was the last point of civilization at the edge of the new American West. With vivid detail, historian Brady Crytzer traces the full history of Fort Pitt, from empire outpost to a bastion on the frontlines of a new republic.Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fort Pitt by Brady J Crytzer in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9781614236917Subtopic

Early American HistoryCHAPTER 1

HUGH MERCER

“CAPABLE OF A TOLERABLE DEFENCE”

The following was taken from a letter dated December 26, 1758: “When your Works are finished, Would it not be of good Service to you to build a Redout (wth fraises) for 60 men on the Top of the Hill over Monongahela. It would prevent the Ennemies taking Post there and secure a Retreat.”1

It had been weeks since Lieutenant Colonel Hugh Mercer had seen his superior, but in typical fashion, Colonel Henry Bouquet was in constant contact. Though he was a great distance away across the unfamiliar landscape of Pennsylvania, Henry Bouquet’s regular correspondence granted him a complete picture of the progress and obstacles faced by his lone detachment left at the Forks of the Ohio. A month earlier, after a triumphant and bloodless taking of Fort Duquesne led by General John Forbes, Mercer was surprised to receive the duty of remaining behind, along with two hundred others, to build a temporary fortification at the strategic locale. Those two hundred were not British regulars but rather colonial militiamen from Pennsylvania and Virginia. While the natives of the region had been recent newcomers in their own right, the now absent Forbes had finally given it a name that would resonate on the European continent: Pittsburgh. Named after Secretary of State William Pitt, the man responsible for devising the strategy to conquer it, the place where the Three Rivers touched would now be identifiable on a map in a library an ocean away.

Though Mercer knew that the outpost he was instructed to build would not be permanent, he was aware that it had to be built quickly; two hundred men could rapidly succumb during a harsh winter in the Ohio Country. Mercer took solace in the fact that he had played a key role in reclaiming the strategic position from the French empire, and the war in North America was now greatly tipped in Britain’s favor; a French victory in the Seven Years’ War was becoming increasingly unlikely.

Colonel Hugh Mercer. Born in Scotland, his legendary military career would be first tried at the Forks of the Ohio. From The Life of General Hugh Mercer (1906).

Orders to build an outpost that could be easily abandoned came as an instinctive comfort to Mercer. For most of his adult life, he had been on the run, either as a wanted man or a hunted one. Born as the son of a Presbyterian minister in 1726 at Aberdeenshire, Scotland, Mercer’s teenage years did not indicate that he would become a soldier. At the age of fifteen, Mercer attended the University of Aberdeen, Marischal College, and graduated a doctor. Four years later, however, Mercer’s life took a drastic turn. In an effort to place himself where he believed he was most needed, the nineteen-year-old joined the ranks of Charles Edward Stuart’s Jacobite Army as a surgeon. Stuart’s coup would fail, and his army would be defeated at the Battle of Culloden in 1746, and overnight Mercer was transformed from a battlefield physician to a traitor and, subsequently, a fugitive. After months of hiding, and fearing for his life, Mercer was able to book passage on a transatlantic vessel to America, where he settled in central Pennsylvania.

For Mercer, this duty had been his first of total command during Forbes’s eight-month expedition from Philadelphia, but leading in this unforgiving part of the world was nothing new to him. He first became involved in the combat three years earlier when, after reprising his role of medic, he administered care to the wounded of Braddock’s Defeat. The horrors of frontier combat harkened back to the haunting experiences in his homeland from a decade earlier, and with a sense of honor and duty, Mercer’s title was promptly changed from doctor to captain. Serving in the Pennsylvania militia, Mercer played an integral role in John Armstrong’s 1756 expedition against Kittanning.2 During the expedition, Mercer was shot through the wrist and separated during a chaotic retreat. For fourteen grueling days, the injured Mercer desperately clawed his way to Fort Lyttleton, all the while avoiding Indian capture and surviving on a potent diet of rattlesnake and wild berries.3

Now, after rising to the rank of lieutenant colonel, Mercer was again in the Ohio Country, and the success of the British empire appeared to be at his feet. For most of the Forbes expedition, Mercer had been a subordinate, a cog in the machine of war. He had marched as part of Colonel Henry Bouquet’s detachment from Fort Ligonier as part of a three-headed army destined for the confluence of the three rivers. The other two columns were led by Colonels Archibald Montgomery, a fellow Scotsman, and the Virginian George Washington. Washington and Mercer, though never having met before 1758, would have discussed the particulars of the Forks of the Ohio throughout the eight-month mission. The Virginian had visited the site before any flag flew over during his 1753 mission to Fort LeBoeuf, and the two men grew to become dear friends.

Despite their blossoming relationship, Washington had also left the position after its conquest; holding it would fall to Mercer. With his commanding officer never far removed through their weekly writings, Mercer would take into account the requests of Bouquet. On his instruction, the colonel built his temporary outpost along the shores of the Monongahela River. With the smoldering remains of Fort Duquesne still smoking, Bouquet instructed the men to salvage any ironworks or square logs from the ashes.

Time was of the essence.

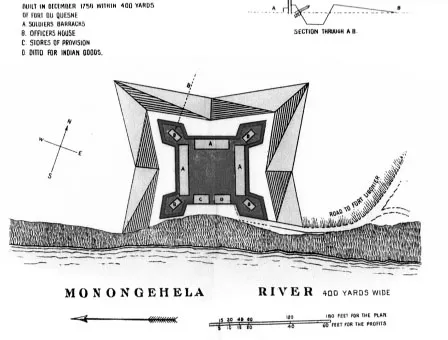

MERCER’S FORT

Recalling his previous experiences fighting Indians, Mercer designed the fort with efficiency in mind. It would be simple, built around a framework of barracks for his men. There would be no time to build an extensive outer wall, or palisade, of any kind, so the long rectangular barracks would serve as the first line of defense. Between each barracks, however, Mercer instructed his men to build a quartet of four-sided, European-style bastions. These diamond-shaped structures were vital to any modern fort, and they allowed for the elimination of any blind spots that one might encounter when attempting to fire down on an encroaching enemy. Inside of each bastion would sit a specialized component of the fort. In the northwest would be the bombardiers’ quarters, and the northeast would house the officers. On the southern face of the fort, which ran along the river, the southeast and southwest bastion would hold the powder magazine and hospital, respectively. In the center of the fort, the best-defended location would be Mercer’s quarters.4

For Mercer, and those above him, producing a strong fort at the location was not nearly as important as simply maintaining a presence early on; the Pennsylvanians and Virginians would serve that purpose. For the time being, the British had control of the Forks, and unlike just five years earlier, keeping control would be much less difficult. By 1753 and 1754, the French had constructed three fortified positions in the Ohio Country: Forts Presque Isle, LeBoeuf and Machault; it was only natural that the next position south would be the Forks. That spring, a force from Fort Machault hastily established Fort Duquesne. It remained for four years.

The deadly game of chess, however, changed rather drastically in 1758, as the British had also constructed a series of forts that could easily access the strategic position. Established along the road carved out by Forbes’s expedition, Forts Loudon, Bedford and Ligonier all created a direct connection from the colonial capital of Philadelphia to the Forks of the Ohio.

William Pitt, British secretary of state responsible for the strategic adjustment allowing for the capture of Fort Duquesne. Though he would never see the outpost, Pittsburgh is his namesake. From Fort Duquesne and Fort Pitt (1899).

Forts of the period were essential to winning a wilderness campaign. Though they housed small garrisons of soldiers, the true value and strength of a single fort paled in comparison to that of a string of forts. More than just a set of protective walls in an untamed wild, forts like those constructed by the French and British served as vital lines of communication. With the success of Forbes’s campaign, Great Britain now had a direct path that allowed an endless supply of goods, manpower and information to flow freely for more than three hundred miles. If the French were to attack Mercer’s position, a British response from Fort Ligonier would arrive quickly on the scene and undo any advance made by their enemies. In a game that is often decided by punctuality of reinforcements, Philadelphia was much closer than Montreal, and the British were well aware of that advantage.

The danger of a French assault on their new position was a present one for the British, hence Bouquet’s orders to ensure a reasonable escape route for Mercer’s men. Mercer, though, knew that his preparation would need to be calculated, as the most likely threat would be of Indian, not French, attack. Though his fort was modest, Mercer had faith that it could stave off an Indian ambush if necessary; he did not feel so confident about fending off French regulars. Because the nearest French threat was Fort Machault, almost eighty-five miles away, the attack would have to come southward along the Allegheny River. With this in mind, it seems only natural that Mercer would position his outpost directly beside the Monongahela River. If the French did advance, Mercer and his men could easily abandon the position by escaping downriver, and a much stronger British counterattack could be launched from the east.

There was so little urgency from London in keeping the fort that even Secretary of State Pitt, Britain’s master strategist, believed that a simple blockhouse, rather than a fort, would have been sufficient to construct at the site. Fortune had truly shined on the British empire.

Mercer’s construction project was fraught with logistical difficulties from the beginning. Because of winter conditions, the ground was a frozen mass, unyielding to the picks and axes of Mercer’s men; though a trench was dug, it was not done without a fight. Though there was a plentiful supply of trees for the men to cut down, the frozen rivers did not allow their recently harvested efforts to be transported to Mercer’s location. As winter progressed, the colonel’s fort was coming together, quite literally, piece by piece.

Mercer expressed his intentions to fortify and hold the location to Bouquet in this letter, dated December 19: “I expect in four Days to have the Place made capable of a tolerable Defence, and am fully determined to maintain the Post, or at least, make it as dear a Purchase to the Enemy as possible.”5

Today, many historians refer to this bold little outpost as Mercer’s Fort, though there is little evidence to suggest that it was ever actually given a proper name. There is some debate as to how permanent Mercer believed his fort would be, and the fact that it was never named indicates that its transitory status was well known even in 1758. Despite this belief, Mercer’s Fort was in a vital spot, and it would exist as the primary location for Anglo-Indian diplomacy in the region well into 1759; the evidence of that is available as early as January. Among the many small cabins built outside of the fort, one was designated specifically as a Council House for meetings with prominent Indian sachems.6

The twenty-five-year-old George Washington during his many exploits in the war for empire. From A Century and a Half of Pittsburg and her People (1908).

Shortly after establishing themselves at the Forks, the British were once again interacting on a regular basis with the various Indian groups of the regions. Due to greater allegiances, many of the tribes long associated with the French (because of the presence of Fort Duquesne) remained belligerent toward the British. Although some followed the French north during their retreat, others with more investment in the region and less with the now absent French began to deal in kind with Mercer and his men. According to his notes, in one such meeting a delegation of representatives of the Iroquois Confederacy met with the colonel to discuss their future in the region and ask for meaningful aid in the form of open support. Since the founding of Fort Duquesne five years earlier, the Iroquois had seemingly lost their imperial grip over the various peoples of the Ohio River Valley. By making unilateral decisions, groups such as the Delawares, Shawnees and Mingos (collectively referred to from this point as the Ohio Indians) violated the basic tenets of living under Iroquois domain. By electing to side with the French at Fort Duquesne, the Ohio Indians served to undermine the stature of the Confederacy in the region and further lessen its influence and role in the larger scope of the war for empire.7

LOGISTICS

Another common problem faced by Mercer and his men was the lack of provisions for supporting a body such as theirs. For much of December, the Pennsylvanians and Virginians ate from the rations that had been left behind by the occupants of Fort Duquesne. Duquesne, a small but considerably more substantial fortification, had a plentiful supply of locally grown goods to feed its men. When the fort was destroyed, the food within was lost in turn; however, the large plots of fertile wheat and corn outside its walls were largely intact. As the winter wore on and the deep chill of January and February bore down, Mercer was forced to be mindful of his exposed stores. He frequently wrote that basic provisions such as flour and corn were in short supply and often consumed hastily by the native peoples of the region. As mentioned in a letter to Bouquet, Mercer claimed that one tactic he had experimented with was asking the Indians who frequented his outpost to send their wives and children home, leaving only those hunters able to produce regular kills of venison, turkey and other wild prey.

Life at Mercer’s Fort was utilitarian and simple. Though in hindsight historians frequently consider the fort as less consequential than its predecessor and successor, a concentrated French attack would have most certainly overrun it. That belief is not meant as a critique on the outpost’s defensive capabilities, but it is simply an acknowledgement of the fact that it was designed for prompt and methodical evacuation by those inside. Despite the fact that an attack on the position never came, fort life during the period was tense and fearful. The duplicitous Indians whom Mercer and his men dealt with every day often warned of encroaching forces or future invasions that never came. In one case, word was spread in July 1759 that seven hundred Frenchmen and seven hundred Indians were amassing at Fort Machault (present-day Franklin, Pennsylvania) for an assault on the isolated position. Unknowingly, as Mercer’s men prepared for the inevitable by burning every small structure outside of the fort except the Indian Council House, the Franco-Indian force was redirected and called on by Montreal to assist in breaking the siege of Fort Niagara some 250 miles to its north.

Though modest and hurried, Mercer’s Fort would secure the Forks of the Ohio for the British until further arrangements could be made. From Report of the Commission to Locate the Sites of the Frontier Forts of Pennsylvania (1895).

A NEW FORT

As spring approached, significant progress had been made in the thawing of the soil that a variety of earthworks could be created. Mercer continued his correspondence with Bouquet, and the colonel back east requested that Mercer seek out a new location, one desirable for a more perman...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Prologue. Streets of a Thousand Names

- Chapter 1. Hugh Mercer: “Capable of a Tolerable Defence”

- Chapter 2. John Stanwix: “A Perfect Tranquility”

- Chapter 3. Robert Monckton: “The Brave, Open-hearted, and Liberal”

- Chapter 4. Simeon Ecuyer: “Every One Works, and I Do Not Sleep”

- Chapter 5. Henry Bouquet: Fort Pitt and the Ohio Insurgency

- Chapter 6. Lord Dunmore: Pittsburgh in the Old Dominion

- Chapter 7. Daniel Brodhead: Fort Pitt and the American Revolution

- Epilogue

- Appendix. The Hanna’s Town Resolves

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Author