- 235 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Hidden History of New Jersey at War

About this book

The Garden State has made innumerable contributions to our nation's military history, on both battlefield and homefront, but many of those stories remain hidden within the larger national narrative. Perhaps the most crucial one-day battle of the Revolution was fought in Monmouth County, and New Jersey officers engineered the conquest of California in the Mexican War. During the Civil War, a New Jersey unit was instrumental in saving Washington, D.C., from Confederate capture. In World War II, New Jersey women flocked to war production factories and served in the armed forces, and a West Orange girl helped ferry Spitfire fighters in England. War came home to the coast in 1942 with the sinking of the SS "Resor" by a German submarine, but the state's citizens reacted by contributing everything they could to the war effort. Uncover these and other stories from New Jersey's hidden wartime history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hidden History of New Jersey at War by Joseph G Bilby,James M. Madden,Harry Ziegler in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

THE FIRST SHOT

The first verified fatal shot fired by residents of New Jersey directed against an outside enemy was from a bow, not a gun.

Before the coming of the Europeans, the Lenape, New Jersey’s Native American people, were inhabitants of the larger homeland of Lenapehoking, a territory covering portions of several modern states, including New York, Maryland, Pennsylvania and Delaware, as well as New Jersey. The Lenape were members of the Minsi or Munsee (north) and Unami (central and south) language subgroups. As far as modern archaeologists can estimate, they and their forebears had been residents of Lenapehoking for up to twelve thousand years.

The original meaning of the word “Lenape,” which has slight variant pronunciations in Minsi and Unami, has been variously interpreted and disputed over the years. Late Seton Hall University archaeologist Herbert Kraft, the leading expert on New Jersey’s Indians, wrote that it might have several meanings, including “real person,” or “men of the same nation.” The Lenape were not a “nation” in the European sense of the word but an aggregation of small bands of connected families with a similar language, although Unami and Munsee speakers were not necessarily completely intelligible to each other.

The limited number of warriors available, coupled with local feuds between bands—Lenape in central New Jersey, for example, reputedly detested those living on Manhattan Island—and a decentralized political structure severely limited overall Lenape war-making capability, as raising significant military organizations and engaging in large-scale combat involving heavy casualties and widespread destruction were impossible. One early European observer noted that “it is a great fight where seven or eight is slain.” Inter-band violence did occur, as evidenced by the discovery, in 1895, of a Staten Island burial in which the deceased was apparently shot by thirty-three arrows, but it was limited in scope. We have no written or traditional accounts of what these conflicts were about, but squabbles over hunting and fishing territories or personal enmity based on some sort of grudge can be assumed. Kraft, however, reported that “very few” excavated Lenape burials “show evidence of warfare or death through violence.”

At the time of European contact, the chief Lenape weapon was the “self bow,” which, although similar in length, contrasted unfavorably in power with the English longbow, as well as the composite or laminate bow used by other Native Americans. Hand-to-hand combat weapons included war clubs of various types. (A ball-headed club, probably Lenape, from the New Sweden colony along the Delaware River, survives in Skokloster Castle in Sweden.) Arrowheads and knives were chipped from flint at the time of first contact between natives and Europeans. Lenape tactics were simple and limited to ambushes and surprise raids on rival groups. The Lenape code required that killings in war or personal feuds be avenged, but the continual spiral of violence that this belief suggests could be, and usually was, short-circuited by negotiations and payments to relatives of the deceased. Interestingly, in these settlements, the lives of women were apparently considered more important than those of men. Lenape concepts of war and peace, as well as property ownership, would change dramatically with the arrival of Europeans in Lenapehoking.

The first known European to sail along the present New Jersey shore was Giovanni de Verrazzano, an Italian employed by King Francis I of France with orders to find a passage through America to the Orient. In the spring of 1524, Verrazzano reached the coast of today’s North Carolina and then headed north, vainly seeking the nonexistent passage. As the Native Americans along the shore of Lenapehoking observed Verrazzano’s ship, La Dauphine, glide by, it is doubtful that they remotely anticipated what was in store for them and their descendants over the next two centuries. One thing that can be said for sure, however, is that they were not afraid of the Europeans. When La Dauphine rounded Sandy Hook into Raritan Bay, which Verrazzano called Santa Margarita, large numbers of Lenape rushed down to the shore with great excitement, launching canoes to get a closer look at the white men. Prevailing winds prevented a landing, however, postponing a face-to-face meeting between Lenape and Europeans. There is no existing evidence of any closer encounters between the two cultures for the rest of the sixteenth century, although one or more are certainly possible, even probable, considering that a number of European fishermen and explorers sailed into American waters over those years.

The next verifiable contact between the Lenape and Europeans in what is now New Jersey occurred when Henry Hudson, an Englishman exploring on behalf of the Dutch, entered Raritan Bay in 1609. The Dutch had created an independent state from an obscure province of Spain that then became the Netherlands, a rising maritime power in the seventeenth-century world. Hudson, yet another explorer seeking the elusive “Northwest Passage” through North America to the Orient, was the first European to make documented physical contact with the Lenape of present-day New Jersey. As in 1524, the Indians demonstrated no fear of their visitors, but on this occasion, what began as a series of seemingly innocuous trading opportunities ended badly. The lack of trust, cultural insensitivity, bullying and outright theft that Hudson’s men displayed during a number of forays into Raritan and New York Bays resulted in several deadly incidents, including one in which a sailor was killed when hit in the throat by a flint-tipped arrow and another in which eight or ten Lenape were blown out of the water and several canoes sunk by small arms and artillery fire from Hudson’s ship, the Half Moon. The unfortunate European fatality, one John Colman, was reportedly buried on Sandy Hook, the first recorded European combat casualty suffered in today’s New Jersey. Likewise, the unnamed Lenape sprayed with fire from Hudson’s ship were the first New Jerseyans to become combat casualties. Hudson had more luck trading farther up the river that today bears his name, where he swapped some metal hatchets and hoes, whiskey and wine for beaver pelts, corn and tobacco.

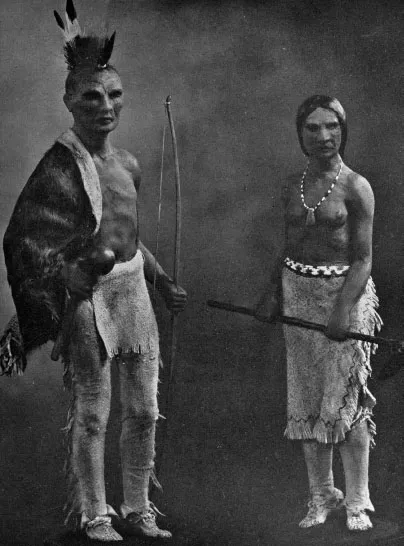

A Lenape village at the time of Henry Hudson’s voyage, as portrayed in a 1930 diorama at the Public Museum of Staten Island. From Kull, New Jersey History.

Francis Davis Millet’s Repulse of the Dutch, depicting the 1609 death of John Colman, in the Hudson County Courthouse. Jersey City Free Public Library.

A late nineteenth-century impression of the Lenape first shot and death of Colman, a mural by Francis Davis Millet entitled Repulse of the Dutch, endures in the Hudson County Courthouse in Jersey City to this day, although the victim in this case was, as was Hudson, English-born. Millet, a Massachusetts native, Civil War veteran, Harvard graduate, international celebrity artist, war correspondent and possible lover of travel writer Charles Warren Stoddard, was considered by many the best muralist of his day. Born in 1848, he died in the sinking of the Titanic on April 15, 1912.

The only surviving account of Hudson’s voyage and Colman’s death is in a journal kept by Robert Juet, a member of Hudson’s crew. What follows is an account of the first shot from Robert Juet’s journal of the Hudson voyage:

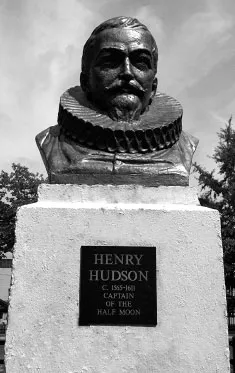

A bust statue of Henry Hudson, in memory of his exploratory voyage, stands in Jersey City’s Riverside Park. James M. Madden.

The sixth [of September 1609], in the morning, was faire weather, and our Master sent John Colman, with foure other men in our Boate, over to the North-side to sound the other River, being foure leagues from us. They found by the way shoald [shallow] water, two fathoms; but at the North of the River eighteen, and twentie fathoms, and very good riding for Ships; and a narrow River to the Westward, betweene two Ilands. The Lands, they told us, were as pleasant with Grasse and Flowers and goodly Trees as ever they had seene, and very sweet smells came from them. So they went in two leagues and saw an open Sea, and returned; and as they came backe, they were set upon by two Canoes, the one having twelve, the other fourteene men. The night came on, and it began to rayne, so that their Match went out; and they had one man slaine in the fight, which was an English-man, named John Colman, with an Arrow shot into his throat, and two more hurt. It grew so darke that they could not find the ship that night, but labored to and fro on their Oares. They had so great a streame, that their grapnell would not hold them.

Henry Hudson’s ship the Half Moon as portrayed in a nineteenth-century account of his voyage. James M. Madden.

For further reading, see Kraft, Lenape-Delaware Indian Heritage; Dowd, The Indians of New Jersey; Boyd, Atlantic Highlands; Moss, Monmouth: Our Indian Heritage; and Lender, One State in Arms.

CHAPTER 2

KIEFT’S WAR

Henry Hudson failed to discover a northwest passage, but his success in trading trinkets and liquor for valuable furs inspired Dutch merchants to follow in his wake. They established a trading post called Fort Orange at today’s Albany and may also have built another temporary post on the site of modern Jersey City in 1614.

Control over the growing colony of New Netherland was granted to the Dutch West India Company, and in 1624, the company founded several settlements, including New Amsterdam on Manhattan Island, to provide support and supplies to the trading posts. Many early settlers were not “Dutch” as the term is understood today and included Walloons from what is now Belgium and French Huguenots and other groups fleeing religious wars and persecution in Europe. New Netherland became an extremely diverse place, and by one account, there were eighteen different languages in use in the capital, New Amsterdam, in 1643.

In an attempt to encourage more settlements, the company granted “patroonships,” or large plots of land, along the North (Hudson) River to wealthy merchants, who were, in turn, obligated to establish farming communities on the grants. Michiel Reyniersz Pauw received such a grant across the river from New Amsterdam in 1630. His land, called Pavonia after him, stretched from modern Staten Island to Hoboken and was the first permanent European settlement in today’s New Jersey.

Few colonists moved to Pauw’s Pavonia. It reverted to West India Company control, and the company leased land to settlers who combined farming with fur trading. Pavonia grew slowly, as tension increased between settlers and natives. European domestic animals wandered through Indian fields, rooting up maize and bean crops. Lenape dogs harassed the trespassing pigs and cattle in turn, and trade cheating by the Dutch and petty theft by the Indians escalated. War was perhaps inevitable, but New Netherland director general Willem Kieft dramatically accelerated the downward spiral in relations following his arrival at New Amsterdam in 1637.

Lenape man and woman in the seventeenth century, as portrayed in a 1930 diorama at the American Museum of Natural History. From Kull, History of New Jersey.

Early on, Kieft ordered an attack on a band of Raritan Lenape for allegedly stealing pigs on Staten Island and then levied an arbitrary tax on local Native Americans and threatened to attack them if it was not paid. He was apparently trying to provoke a conflict he had no doubt he would win. Over the winter of 1642–43, a band of Wiechquaeskeck Lenape, driven south by marauding Mohawk, fled to New Amsterdam and then crossed the North River to the vicinity of Pavonia, where they sought refuge with the local Hackensack band.

On February 23, 1643, Kieft ordered his soldiers to conduct a surprise night attack on the refugees and Hackensacks. David Pieterz de Vries, a Dutchman who opposed Kieft, recalled, “I heard a great shrieking…and I looked over to Pavonia. Saw nothing but firing, and heard the shrieks of the savages murdered in their sleep.” Kieft’s troops indiscriminately killed men, women and children. Some of the latter, according to De Vries, were “hacked to pieces in the presence of the parents, and the pieces thrown into the fire and in the water.” De Vries wrote that some soldiers brought human heads back across the river as trophies. Another colonist described the events as “a disgrace to our nation.”

Kieft’s troops, known as “sea soldiers” due to their overseas assignment to the colonies, were one-year contract employees of the West India Company. The majority of them were apparently Germans who drifted into the Netherlands seeking work, although some were English, French or Scandinavian. They were described as “men picked up with no special regard for character, experience or ability” and commanded by “commercial and military adventurers.” On arrival in Amsterdam, these migrants were given food and shelter by innkeepers known as zielverkopers, or “sellers of souls,” who, when the West India Company put out a call for soldiers, produced them. In 1644, a sea soldier enlisted for thirteen guilders a month and an adelborst, or “cadet,” a junior noncommissioned officer, at fifteen guilders a month. The sea soldiers received a two-month advance on their salaries, payable to the zielverkoper for room and board.

Company soldiers were equipped with firearms and edged weapons and perhaps minimal armor but no uniforms. Officers were authorized to wear orange sashes to denote their rank, although these insignias were only worn on special occasions. The training these men received was minimal, and the attention they paid to their military duties was limited as well. The New Amsterdam garrison was between forty and fifty men strong, and by 1644, the town fort’s dimensions were 250 by 300 feet, enclosing a barracks and guardhouse. Smaller garrisons were established at forts throughout the colony, including trading posts along the South (Delaware) River. At its height in 1664, the total military garrison of Dutch New Netherland numbered between 250 and 300 men, 180 of them in New Amsterdam. Director Kieft’s maximum available force of full-time soldiers two decades earlier was significantly smaller.

Kieft’s sea soldiers carried muskets using the matchlock ignition system, in which the gun was fired by squeezing a bar or trigger that lowered a length of glowing potassium nitrate–soaked “match cord” into a pan of priming powder to ignite the main charge. Matchlocks were the most common firearms used by the early settlers of New Netherland. The matchlock survived in Europe as an inexpensive weapon to equip large armies to the end of the seventeenth century, but the firearms of choice for individual colonists in America became the more modern wheellock- or flintlock-ignition guns. These systems, using pyrites or flint to create sparks to ignite the main charge rather than a glowing match cord, were, when properly handled, more reliable in bad weather than the matchlock and could be more rapidly and safely reloaded. By the 1650s, the New Amsterdam government requested that half its troops be armed with wheellocks and the other half with flintlocks. The same officials wanted the personal arms of New Amsterdam settlers restricted to matchlocks, apparently out of fear that they might trade or lose more modern guns through theft to the local Lenape. Ironically, there was a lively Dutch gun trade with the Iroquois through Fort Orange, however, where flintlocks were readily exchanged for furs. By 1650, many Lenape had secured flintlocks from various sources and quickly learned how to use them. One account notes, “They are exceedingly fond of guns, sparing no expense f...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. The First Shot

- 2. Kieft’s War

- 3. Monmouth Courthouse

- 4. Paulus Hook and Camp Jersey City: New Jersey’s War of 1812 Command Center

- 5. The Jersey Boys Take California

- 6. A “Peculiar” History: The Tenth New Jersey Infantry in the Civil War

- 7. Jersey Boys to the Rescue

- 8. The New Jersey National Guard Grows Up: 1895–1921

- 9. Black Tom and Kingsland: The Jersey Mosquitoes Were Not to Blame

- 10. “Heaven, Hell or Hoboken”

- 11. On the Road to War Once More

- 12. “The Finest Thing I Have Seen”: The Immortal Chaplain from Newark

- 13. The Greatest New Jersey War Myth

- 14. A Jersey Girl Goes to War

- 15. The War at Home

- 16. Senator McCarthy Pays a Visit to New Jersey

- 17. New Jersey’s Nikes

- Appendix. New Jersey Historic Military Sites and Museums Worth Visiting

- Bibliography

- About the Authors