- 195 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

For many, Detroit is the crunch capital of the world. More than forty local chip companies once fed the Motor City's never-ending appetite for salty snacks, including New Era, Everkrisp, Krun-Chee, Mello Crisp, Wolverine and Vita-Boy. Only Better Made remains. From the start, the brand was known for light, crisp chips that were near to perfection. Discover how Better Made came to be, how its chips are made and how competition has shaped the industry into what it is today. Bite into the flavorful history of Michigan's most iconic chip as author Karen Dybis explores how Detroit "chipreneurs" rose from garage-based businesses to become snack food royalty.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Better Made in Michigan by Karen Dybis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Potato Peddlers

What small potatoes we all are compared with what we might be!

–Charles Dudley Warner

In modern-day Detroit, the sprawling façade of the Better Made Snack Food plant serves as a focal point along Gratiot Avenue. It stands out among the churches, gas stations and neighboring houses for a variety of reasons. It is the only manufacturing facility of any kind for miles. After more than a dozen expansions, the factory takes up an entire city block from Gratiot to French Road. There is the red-and-blue “Better Made Quality” sign that stands guard at the building’s front. There are its large glass windows, which give a glimpse of the sizable production lines and freshly fried chips inside. Then there is the dramatic sight of a semi-truck trailer on a hydraulic lift as it is tipped to deliver a load of forty-five thousand to eighty-five thousand pounds of potatoes.

Inside, something amazing is about to happen. In about seven minutes, those potatoes will go from a raw tuber, still coated with the earth in which it grew, to a Better Made potato chip. From that truck, potatoes pour in through a small window to the facility. They are bounced along a conveyor belt to bright-blue storage bins. This is the area where it pays to linger; the odor of soil and fresh potatoes is so strong that you will smell it long after you have left the factory. It is the kind of scent memory that moves you, reminding you of this nation’s farming heritage and the goodness of eating something fresh from the ground.

Those potatoes selected are transported to a machine that washes the spuds to remove any field dirt or contaminants. A machine peels the outer layer off in seconds. From there, another machine slices them to a precise width. Once a Better Made employee inspects the potatoes to remove any of poor quality and ensure that they are of uniform size, they are off to a temperature-controlled cooker. They are fried in oil for about three to four minutes. A machine salts the chips while they are still hot and moist. Any flavoring, such as the seasoning for the legendary barbecue flavor, comes next. The finished product moves along an overhead vibrating conveyor system to automatic packing machines that weigh, fill and seal the bags. Workers put the bags inside cartons, which are taped shut and moved to the Better Made warehouse for distribution to grocery stores, convenience markets and other outlets across Michigan and a handful of other states.

Some 60 million pounds of potatoes go through the plant annually, producing an impressive amount of potato chips. But that’s not all Better Made does. In fact, President Mark Winkelman describes the company as a “snack food distributor that makes potato chips” for good reason. Besides manufacturing chips, potato sticks and popcorn on site, Better Made creates private-label products for retailers and distributes a variety of snack foods with its labeling to stores regionally. There’s corn pops, party mix, cheddar fries, cheese curls, corn chips, tortilla chips, pork rinds, cracklins, salsas, dips, rubs, licorice, beef jerky, nuts and more, all finding their way to store shelves because of Better Made’s distribution prowess. It is what diversifies the company, Winkelman said, keeping it profitable beyond Detroit’s sizable and notable chip obsession.

It is, without a doubt, a far different company than the one that started in the 1920s in the kitchens of Cross Moceri and Pete Cipriano. For them, the potato chip business was something they did in the cool evening hours and peddled door to door in small batches. Among their earliest customers were families picnicking in Detroit’s many parks on the weekends or travelers on one of the city’s streetcars during their busy daily commute. Better Made’s start was so inauspicious that level-headed Cipriano remained a milkman for many years after its creation. Family lore has it that he finally gave up his route around 1941 to keep an eye on his investment in the company, which Moceri had grown into a storefront along East Forest Avenue and then into a larger kitchen along McDougall. A short-lived stay on Woodward Avenue—where the nearby secretarial pools troubled by the smell of frying potatoes would force Better Made to work only at night—would take the company to its current Gratiot Avenue location by 1949.

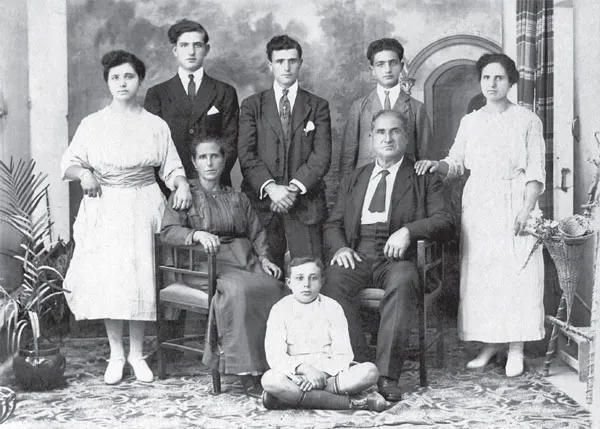

Pietro “Pete” Cipriano was one of nine children. A 1913 family portrait features six of the siblings along with Pete’s beloved father and mother, Isadore and Catherine. Cipriano family collection.

The best way to understand the powerful legacy of Better Made and that of Detroit’s “chipreneurs” is to look back at the city’s development, its entrepreneurial landscape and the families who created these companies. Over the twentieth century, there is evidence that there were about forty potato chip businesses of various sizes selling potato chips in the Motor City. Most started as and remained home-based chippers, selling batches of what really were kettle-style chips. A dozen or so would become household names, including brands such as Everkrisp, Krun-Chee, Superior, Mello Krisp and Wolverine. Less than a handful developed into well-organized businesses that became regional or national players. The most notable example is New Era, the brainchild of Ernest L. Nicolay and Russell V. Dancey, two autoworkers turned potato chip titans.

Many of these chip companies, including Better Made, were started by immigrants eager for work and looking to create jobs for other newcomers from their homeland to Detroit. In the case of New Era, it was a business that grew out of the ambition of a farmer’s son who wanted success that did not depend on Mother Nature. These were men who saw a city with immense hunger, literally and figuratively. In Detroit, they could grow alongside the population, the city’s towering skyscrapers and its powerful automotive manufacturers. They could take their first years of struggle, harsh working conditions and desperation and channel them into their own enterprises, many of which created fortunes that have lasted well into the second and third generations.

So where did the idea for these delicious treats start? Theories vary, but researchers have found recipes for potato chips in cookbooks from the early nineteenth century. Most potato chip historians say that the salty snack as most people know it was invented in about 1853, when Chef George Crum worked at Moon’s Lake House in Saratoga Springs, New York. That tale centers on Crum dropping a thinly shaved potato in the fryer to serve to a finicky customer who had returned their potatoes for being too thick. Another version has Crum’s sister, Katie, inventing what is known as a potato chip when she accidentally dropped a potato slice in the kitchen’s fryer. In recent years, however, a small group of folklore historians who have studied the story have noted that a secondary chef known as Eliza was the likely inventor. She was known for “crisping potatoes,” building a potato-frying reputation in Saratoga around the late 1840s. Eliza Loomis, who owned the Lake House, is the likely culprit. Loomis worked in the kitchen, as most managers would have, and there are various newspaper articles that report customers enjoying crispy potato slices there years before Crum arrived. By one account, the Lake House had built such a reputation for its chips that in 1866 it started selling them in portable paper cornucopias so visitors could take some home with them. For decades, the so-called Saratoga Chips would become a staple in area restaurants’ menus, a fad item to serve as a side dish.

The transition from restaurants to commercial production likely began in the late 1890s. William Tappenden of Cleveland, Ohio, tends to receive credit for the mass production of potato chips. The Snack Food Association describes Tappenden as “a familiar figure on Cleveland’s streets, delivering potato chips to neighborhood stores in his horse-drawn wagon.” He is credited with opening the first potato chip factory in 1895 in a barn at the back of his house when chip demand outgrew his stovetop production. According to one source, he listed “potato chips” as his occupation in the 1900 census. Dirk Burhans, author of Crunch!: A History of the Great American Potato Chip, hypothesized that cities across the United States probably had salesmen like Tappenden, hawking chips to restaurants or those he passed by en route to his deliveries. Tappenden’s association with an early version of the Snack Food Association also may have given rise to his name as the potato chip processing pioneer.

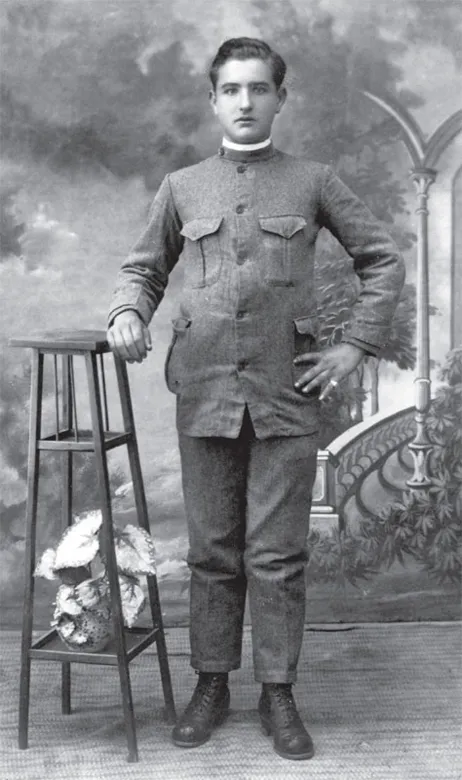

Pete Cipriano in 1918. He would have been around fourteen when this portrait was done in Terrasini, Sicily, his hometown. Cipriano family collection.

As their popularity grew, potato chips started showing up for sale at bakeries, confectionery stores and restaurants across the nation. There were no distributors or salesmen; all of these potato chips were made in-house and served straight from the fryer. Retailers handed them to customers in paper sacks, scooping them to order out of cracker barrels or from glass display cases. As a result, potato chip historians describe this period from the 1850s to the 1920s as the “Cracker Barrel Era.” By the 1910s, Burhans wrote, “potato chips were still mostly a cottage industry; if they were not produced and consumed solely within the confines of a restaurant, they were sold within a few miles from where they were produced. Served from baskets, bins or in plain paper bags, they had little or nothing in the way of recognizable brand names, publicity or associated advertising.”

Some of the first chip companies started to show up from 1910 and into the 1920s, gaining steam as the Roaring Twenties pumped up the United States. During this decade, Americans moved away from the farm in record numbers and began filling the cities. The nation’s total wealth more than doubled between 1920 and 1929, creating what some called a “consumer society,” where people had discretionary income and the leisure time to enjoy it. They bought ready-to-wear clothing, enjoyed the first versions of household appliances and cranked up their radios for entertainment. A little station called 8MK in Detroit broadcast the first radio-news program on August 31, 1920—it is known today as all-news station WWJ-AM 950. Americans also became enamored of movie houses and watching films; by the end of the 1920s, an estimated three-fourths of the U.S. population is said to have visited a movie theater on a weekly basis.

Detroit was a city on the rise as well, building fast and high. Some of its greatest architectural accomplishments came during that decade, filling the city’s horizon. There is the dramatic Book-Cadillac Hotel, which had more than 1,200 guest rooms within thirty-three stories, making it the largest hotel in the world when it opened in 1924. The Penobscot Building, with its impressive forty-seven stories, stood as the eighth-tallest building in the world upon its completion in 1928. Other monumental facilities came online during that decade, making Detroit a city known for transportation of all kinds. In November 1929, the Ambassador Bridge was opened to traffic. And the Detroit-Windsor tunnel was just months away from completion, opening in November 1930. “Flush with money, confidence, optimism and civic pride, [Detroiters] embarked on a building spree—hotels, schools, clubhouses, office towers, airports, factories, golf courses, tunnels, libraries, music halls, theaters, subdivisions, an international bridge and a stadium—that was surpassed by only New York and Chicago during this period,” according to author Richard Bak.

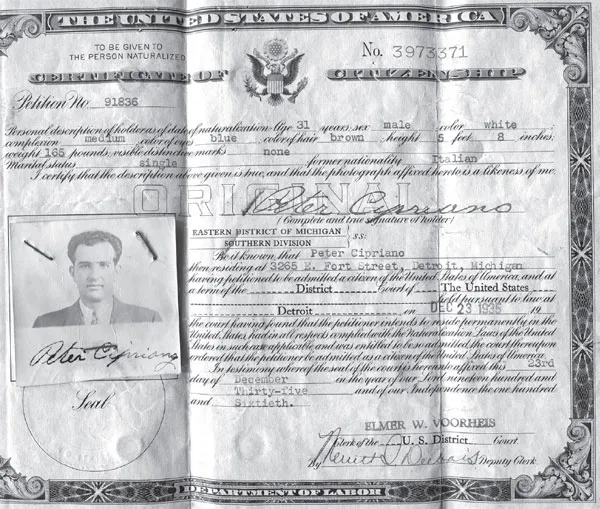

Signing as “Peter Cipriano,” the Better Made co-founder became a U.S. citizen on December 23, 1935. The certificate lists him as thirty-one years old with a medium complexion, blue eyes, brown hair and a height of five feet, eight inches. Cipriano family collection.

Detroit also had become an epicenter for immigrants looking for jobs and a chance at the American dream. “Detroit’s foreign-born population numbered more than 156,000 in 1910, a figure that doubled within 10 years. In 1925, roughly half of the city’s 1,242,044 residents had been born outside of the United States, the largest percentage of any city in the country. These included 115,069 Poles, 49,427 Russians and 42,457 Italians,” Bak wrote. Between the years of 1920 and 1929, Detroit added more than 500,000 people to its population. By the end of that decade, an estimated 30 percent of its residents were working in factories, mostly within the automotive industry.

The demand for products from those factories was so great that Detroit advertised for workers throughout the United States, promising high wages to anyone who would pack up and move. During this time, the city’s size expanded to accommodate these new residents, going from 83.0 square miles in 1920 to 139.6 square miles by 1926. When Cross Moceri arrived in 1910, Detroit’s population was 465,755 people. When Peter Cipriano came about ten years later, that number had increased to nearly 1 million.

Both Moceri and Cipriano came to the United States from Terrasini, a small city on the island of Sicily located about nineteen miles west of Palermo between the mountains and the Gulf of Castellammare. Its name, which in Latin means “terra sinus” or “land at the gulf,” is said to have been inspired by the strongly curved coastline. Although Terrasini’s blue waters must have been difficult to leave, there were no jobs and no future for young men in the area, given the devastation caused by World War I as well as regular drought conditions, said Sal Cipriano, Pete Cipriano’s son. By 1920, some 4 million Italians had come to the United States, accounting for an estimated 10 percent of the country’s foreign-born population. “There was no work in Terrasini; the economy was terrible,” Sal Cipriano said. “America was the promised land. There was industry here: cars, railroad cars, cast-iron stoves. You name it. The jobs and the opportunities were here.”

Cross Moceri was born on May 13, 1898. He sailed from Palermo in March 1910, when he was about twelve years old. His passport application, which lists his father as Giuseppe Moceri, shows that he arrived in Detroit a few months later. Census records from the decade following reveal that Moceri held a variety of jobs, including streetcar conductor. According to U.S. Census records, Moceri was married at age twenty-three to Rosa, then eighteen. He is listed as a widower in the 1930 census with a seven-year-old son, Joseph. Moceri gained his citizenship in June 1921, a few months before Cipriano arrived.

Pietro “Pete” Cipriano was born on April 12, 1904. Cipriano, whose father is listed as Isadore Cipriano, was one of nine children; his siblings included Vincent, Jerome, Rose, Sal, Isidore, Joseph, Grace and Constance. He, too, had limited education; U.S. Census records note that he completed a sixth-grade education. According to family lore, Cipriano always loved to eat and arguably was the best chef in the house. “When he was in Italy, and his mother made steak and potatoes for family, he’d try to trade his steak for his sisters’ potatoes. He loved potatoes,” Sal Cipriano recalled. “When we were older, we used to have those Sunday dinners when everybody came over. He just loved to cook.”

The wedding portrait of Peter and Nicolina “Evelyn” Tocco Cipriano displays her ornate wedding dress and flowers. The two, who both grew up in Terrasini, married in 1937. Cipriano family collection.

At age seventeen, Cipriano sailed out of Palermo with his brother Jerome as a companion across the Atlantic Ocean on the SS Patri. The French ocea...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgement

- Prologue: Oil, Salt and Potatoes

- 1. Potato Peddlers

- 2. Seeds of Growth

- 3. Guaranteed Quality

- 4. The Ringmasters

- 5. The Dream Team

- 6. Balance of Power

- 7. The Worst Deal

- 8. Young, Hungry People

- 9. Fierce Competition

- 10. City Pride

- Epilogue: To Be the Best

- Selected Bibliography

- About the Author