- 147 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

New Jersey's Lost Piney Culture

About this book

Deep within the heart of the New Jersey Pine Barrens, the Piney people have built a vibrant culture and industry from working the natural landscape around them. Foraging skills learned from the local Lenapes were passed down through generations of Piney families who gathered many of the same wild floral products that became staples of the Philadelphia and New York dried flower markets. Important figures such as John Richardson have sought to lift the Pineys from rural poverty by recording and marketing their craftsmanship. As the state government sought to preserve the Pine Barrens and develop the region, Piney culture was frequently threatened and stigmatized. Author and advocate William J. Lewis charts the history of the Pineys, what being a Piney means today and their legacy among the beauty of the Pine Barrens.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access New Jersey's Lost Piney Culture by William J Lewis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Twentieth-Century Piney Defined

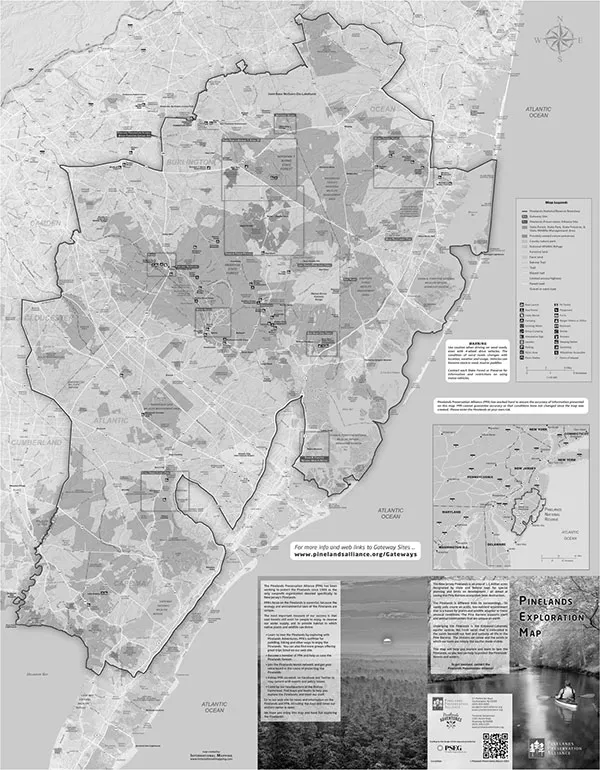

The website of nonprofit 501c3 Pinelands Preservation Alliance (PPA), whose mission it is to help defend the Pine Barrens, states, “The ‘Pinelands’ is an area of 1.1 million acres designated for special growth management rules. It is one of America’s foremost efforts to control growth so that people and the rest of nature can live compatibly, preserving vast stretches of forest, rare species of plants and wildlife, and vulnerable freshwater aquifers.” The website Recreation.gov states that the area “includes portions of seven southern New Jersey counties, and encompasses over one-million acres of farms, forests, and wetlands. It contains 56 communities, from hamlets to suburbs, with over 700,000 permanent residents.” There is an abundance of great books that have already been written about the land within the Pine Barrens.

And there have been a few noteworthy mentions of the people of the Pines collectively called Pineys. John McPhee, in his epic book The Pine Barrens, first printed in 1971, writes, “The Pineys had little fear of their surroundings, from which they drew an adequate living. A yearly cycle evolved that is still practiced, but by no means universally, as it once was.” Our storyline also focuses on what the Pineys gathered or picked seasonally in the woods, which mostly came from the area officially recognized as the New Jersey Pinelands National Reserve, Pinelands for short. They may have ventured to overgrown farm fields on the outskirts of the Pine Barrens to gather grasses.

Pinelands Exploration Map. Courtesy Pinelands Preservation Alliance.

We introduce to you, the reader, one of the unknown champions of many a Piney family: the Richardsons. This family, and more specifically John Richardson, helped Piney families, mostly poor white families, bring to market(s) the 101 items he supplied to big cities like Philadelphia and New York City. The proximity of the Pine Barrens to those big cities brought many an outsider to the area, and their demand for dried floral goods from the region helped sustain Richardson Wholesale Floral Supply. This then, in turn, continued the opportunity for Pineys to live a subsistence living or, as we more commonly call it today, living off the grid to varying degrees of success into the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The life these families lived could be described with the term “working poor,” which highlights the importance of local businessmen and businesswomen who helped them supplement their family income by purchasing items foraged from the surrounding lands. Here we need to make a distinction and note that picking and foraging are used interchangeably. By definition, forage refers to an animal, as defined by Merriam-Webster: “food for animals, especially when taken by browsing or grazing.” Pineys living off the substance of the land foraged for berries and plants for personal use but regularly “picked” items to sell to wholesale dry florists for much-needed income and quick cash.

But what is a Piney? A recurring theme is that Pineys were very private people who often lived simple lives with little modern conveniences. Some would say they were very poor, but that’s by modern standards. Families lived out their lives for generations never traveling out of state and never having left the country. One of my interview questions was what defines a Piney. A friend of many a Piney and outsider of sorts, Johnny Richardson described a Piney as “a person that came from Chatsworth, Browns Mills, Warren Grove areas in the pines. They were adverse to 40 hour normal work weeks. Some were on government assistance and many were known to overindulge in alcohol but all were very honest people. They weren’t materialistic and or schooled but weren’t stupid either. They could build and be very mechanical.” Even though they didn’t have ordinary 9-to-5 jobs, they put in more than forty hours in a week. This was possibly a leftover trait coming from stock that was used to performing twelve- to fourteen-hour workdays in past Pinelands industries like paper, coal, bog iron and farming. Johnny pulled his definition from a lifetime of intimate involvement with the hundreds of Piney families who were supported by his dad’s business.

Speaking from experience, a neighboring farmer to the Richardsons said of the olden times Piney, “The most independent and free people that there ever were in this country that worked in an environment that was very challenging and…they were independent which learned a trade that was passed on by generation to generation. It didn’t fail they weren’t there with their hand out. They weren’t there that needed welfare.” Their fiercely independent nature was due to the remoteness of living in the Pines and having the ability and smarts to adapt to their surroundings. A farmer is tied to the land, and that may have influenced the farmer’s definition of a Piney in that he admired their independence and ability to sustain their way of living not off one set plot of land but the entire Pine Barrens and surrounding open space. But farmers and Pineys were cut from the same cloth. After all, the Reluctant Piney was a farmer but without land, as he got up every morning and went out to harvest the Pineycraft crops that were available and in season—even though, for example, it wasn’t a guarantee that last year’s location of buttons was going to be as good as it was the year before, so they had to keep their eyes on the woods’ picking locations.

Even our federal government wanted to clearly define what a Piney was. The American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., spent four years trying to capture the Piney way of life. The Pinelands Folklife Project was conducted from May 1983 to September 1986 to do just that. I caught up with Dennis McDonald, one of the photojournalists who was contracted to take photos for the Pinelands Folklife Project and author of such titles as Medford (Images of America) and Smithville. When asked about the general feeling and mission of the Pinelands Folklife Project, he stated, “People had an idea of the Pines mostly from the outsiders. Just being a barren landscape between Philadelphia and the Shore. Yes, there were trees, yes, there were sand roads, but beyond that you know I don’t think anyone really knew what went on there and what was the big deal about making it a National Reserve. That seemed odd to people, that it was a bunch of land with nobody in it. The reality was a lot different. People made their living off of a lot of the places in the Pines, as shown in the book. I think they even tried to demonstrate that the culture of the Pines was something that went back generation after generation after generation and was unique to that area.” This was a lofty idea to document the life of the people in the Pines who were multidimensional and at times difficult to find.

This excerpt from the monumental Pinelands Folklife Project’s One Space, Many Places, printed in 1986, brings us closer to defining what a Piney is or was:

Cultural journalists often romanticize Pineys as indigenous, reclusive people who gather pinecones and other native plant materials for a living. Although the gatherers are, in fact, satisfying a very modern demand for the materials in the florist market they are erroneously associated in the public mind with subsistence lifestyles in earlier phases of civilization. For some consumers and purveyors of the region’s folklore, gatherers comprise the undiluted essence of “Pineyness.” Notions of what and who Pineys are comprise a sizeable body of folklore in itself. One woman, a Medford resident, held that Pineys—among whom she does not include lumberers, trappers, farmers, or recently arrived ethnic groups—are the only fitting subject for folklife documentation. Her opinion is reinforced by formulaic presentations of Pine Barrens folklore: Men and women who give lectures on the folklore of the Pine Barrens, they show a pile of pinecones, people who come in with sacks on their backs of things they’ve collected. That, to me, would be what you would be after. That’s Piney culture because it’s gone on for centuries. (Interview, Mary Hufford and Sue Samuelson, November 13, 1983. AMH021)

After years of personal interactions during photoshoots on assignment with the Pinelands Folklife Project, Dennis McDonald suggests a Piney is “someone who made their living off the woods or off the land in the Pine Barrens area. It could be a carver, a farmer, a trapper, any one of the numerous amounts of things. To go beyond that, there are lots of people that I would consider that are Pineys that just love the Pines. They’re nothing more than that. It’s hard to say exactly what a Piney would be, but it’s certainly someone that loves the land probably the number one definition. Unbelievable love of that lifestyle, that land and that resource that we all love to be in.” Two great books were spurred from the key people on the Pinelands Folklife Project: One Space, Many Places by Mary Hufford and Pinelands Folklife, edited by Rita Zorn Moonsammy, David Steven Cohen and Lorraine E. Williams.

In her 1983 PhD dissertation “A Psycho-Social Impact Analysis of Environmental Change in the New Jersey Pine Barrens,” Nora Rubinstein eloquently outlined Pineyness:

Pineyness was based on geographical location at various stages in life, with birth-place being of greatest significance, [then] ancestry, age, occupation, economic status, family ties, and an amorphous quality many comprehend, but few can determine. It is an attitude, a way of being in the world, an essence or quality not included in the legislative description.… [My] search for the elusive Piney has come full circle, from geography and language, ancestry and occupation to an affective sense—a feeling for family, but most important, for the land, for the experience of “being” in the Pines. It is just over the horizon or as Janice Sherwood said, “a little deeper in the woods than you are.”

She tells of being a Piney by your sense of attitude and your love of the Pine Barrens. With Rubinstein’s outline, we come closer to the answer of what a Piney is. It’s that “attitude” part of the description that everyone struggles to define.

This theme of intangible feeling and attitude defining Pineyness is echoed in a book used in collegiate planning courses in New Jersey titled Water, Earth, and Fire by Jonathan Berger and John W. Stinton. They go on to use the term topophilia, or

the attachment to physical places—cemeteries, cedar forests, rivers and lakes, bays, and the old home place. While there is a good deal of mobility in and out of the Pines, those who leave for jobs in the city or a dream farm in Maine return often. It is true that people return to, or even decide to stay in, the Pine Barrens for family reasons, but love of the physical setting in which they grew up plays a major role. There are many residents of the Pines who grew up in some other place but after falling in love with the Pine Barrens came to live in them.

More than anything, the love of the land—that million-plus acres of woods first described as desolate—and that “attitude” mentioned earlier as fiercely independent define what a Piney was and is today. In that loving embrace, the people of the Pines relish in the toughness and the endowments of the land. The remoteness of the Pines brings out the best in them, and the seasonal gifts Mother Earth bestows upon them nourish them year after year.

Chapter 2

Is “Piney” Still a Bad Word?

An anonymous South Jersey farmer spoke about how the generations before the twentieth-century Pineys were more independent and lived a truer life off the land in the Pines. Up until, say, the early 1900s, the Piney way of life depended on hunting, fishing, trapping and harvesting items to supplement the family budget, creating an independence from a modern New Jersey forty-hour workweek their descendants do not enjoy.

On June 28, 1913, Governor James Fielder called Pineys “NJ degenerates.” The governor came out publicly against the people of the region and, ultimately, the Piney way of life all based on lies published in a report by Dr. Henry Goddard and Elizabeth Kite, which had serious ramifications on the Pineys back then and still has effects that continue to be felt to this day. While Governor Fielder used his words and position of power to tear down an entire culture as a plank in his reelection platform, it was John McPhee who ultimately helped save the Pineys with his words, which produced the power to influence a positive change.

The Kite report described the Pineys as inbred heathens. As a result, many state government policies and local government actions were taken against the Piney people, and the Piney world was turned upside down during this time. The New Lisbon Development Center was established in 1914 in the heart of the Pines. Two years later, the Burlington County Colony for Feeble-Minded Boys, which was formerly a branch for the Training School at Vineland also located at New Lisbon, was turned over to the state. Author Robert McGarvey described the times nicely: “The psycho business in the area boomed.”

New state-funded mental wards were established in Burlington County, and both new and old facilities saw an increase in such wards. An excerpt from the Batsto Citizens Gazette read, “The towns and cities had just as many degenerates and feebleminded. There were over 12,300 wards of the State in 1913. The sparsely populated Pinelands probably provided but a fraction of the inmates, but because of their isolation it had been easier to single them out for research.”

Burlington County, the largest county in the state by area, also had the highest proportion of state wards to population. Having been painted as a culture of people who could not avoid their condition because it was hereditary and all-encompassing, the residents of the South Jersey Pine Barrens became even more withdrawn from the public eye, and the Pineys became even more reclusive in nature and suspicious of outsiders. While the science had been refuted by numerous colleagues of Dr. Goddard and Kite and by other experts in the scientific community several times over—Goddard’s study was found to be riddled with false documentation and based on false assumptions that have since been proven wrong—the public condemnation that initially followed the report’s publication is, arguably, the greatest catalyst to the end of the subsistence-living lifestyle of the people of the Pine Barrens and the ultimate extinction of that mold of Piney.

In 1913, researcher Elizabeth Kite published her explosive report, titled The Pineys, that included “tales of heavy drinking, livestock quartered in children’s bedrooms, incest and widespread inbreeding.” The report caused quite a scandal in New Jersey. Governor James T. Fielder made a personal visit to the Pine Barrens, where he found the residents to be “a serious menace” to the public. He stated, “They have inbred, and led lawless and scandalous lives, till they have become a race of imbeciles, criminals and defectives.” Following this visit, he asked the legislature to isolate the area from the rest of the state.

The most infamous Piney who ever lived is Deborah Kallikak. While she herself has been all but forgotten, the Goddard and Kite caricature of her and her Piney roots lives on in the minds of outsiders to the region today. Sadly, the label is still brandished like a red-hot iron cow prod and negatively applied to most residents of South Jersey. The myth that the people of the Pines are inbred, heathens and to be avoided or watched with a close eye but at a far distance when encountered derived from the Kite report and continues to be spread by outsiders.

It wasn’t until the 1985 seminal work Minds Made Feeble: The Myth and Legacy of the Kallikaks, by Dr. David John Smith, that once and for all Deborah and the public image of a Piney were restored in good form, even though we still see the Goddard myth today in 2020. In his book, Dr. Smith stated, “I have attempted to describe the making of a social myth and to illustrate how lives were restricted, damaged, and even destroyed as a result of that myth. In the process of researching and writing it, I have been reminded of, and made more sensitive to, how careful we must be in the sciences and in human service professions about the myths that we accept, foster, or even create. Myths have a way of becoming reality. Myths have a way of gathering force as they are passed along. They have a way of surviving the intent and lifetime of their creators.”

During the various interviews that were conducted for this book, no one could recollect what was published by Dr. Smith and whether it helped at all in lifting the black cloud from the term “Piney.” Did the young Kallikak girl, who was admitted to the Vineland training school in 1897 at the age of eight, even know her own birth name? Her story is so tragic that it could be a Hollywood movie. She lived in state custody until she died in 1978. The actions of a few who “drank the Kool-Aid” poured by Goddard and Kite fully believed that Deborah inherited her intellect—or lack of one—from her mother and that although she exhibited many normal behaviors, her life behind the walls of a sanatorium was justified to keep her from continuing the line of imbeciles and further plaguing the state of New Jersey. This lifelong captivity is a shameful chapter in Piney history.

In Dr. Smith’s book, he stated:

Deborah Kallikak was considered to be “feebleminded.” More specifically, she had been classified as a moron, a designation that Goddard had coined from a Greek word meaning foolish. The label moron came to be widely applied to people who were considered to be “high grade defectives”—those who were not retarded seriously enough to be obvious to the casual observer and who had not been brain-damaged by disease or injury. Morons were characterized as being intellectually dull, socially inadequate, and morally deficient. From the beginning of his research, Goddard was inclined to believe that these traits were hereditary in origin. He was of the opinion that reproduction among people with these traits posed a threat to the social order and the advancement of civilization.

How in the world could science condemn a human condition based on either so little evidence or the incorrect evidence of one Dr. Goddard and one field assistant, Elizabeth Kite—especially when their “research” stemmed from a supposedly “defective” Piney family, the Kallikaks, which rapidly ushered in the sterilization and the eugenics movement in America? Dr. Smith wrote, “The aim of the eugenics movement was to conduct hereditary research that would result in the upgrading of the human stock, similar to the way genetics was being applied in agriculture and animal husbandry. People with superior traits were to be encouraged to reproduce early and often. People with defective characteristics ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. Twentieth-Century Piney Defined

- 2. Is “Piney” Still a Bad Word?

- 3. The Largest Nail in the Reluctant Piney’s Coffin: The Culture of Preservation

- 4. Are Pineys Environmental Heroes?

- 5. Societal Safety Net Suffocates Piney Independence

- 6. Piney Bumper Stickers

- 7. Times a Changin’

- 8. Once Upon a Time: John Richardson’s 101 Items

- 9. Are All Pineys the Same?

- Epilogue. Pineys’ Dirty Little Secret Explained

- Appendix A. Typical Piney Family, Example 1: The Lewises

- Appendix B: Typical Piney Family, Example 2: The Cawleys

- Appendix C. Richardson Calendar

- Appendix D. Example Stories Contained in Forthcoming Book The Richardsons’ Piney Calendar: A Field Guide to the Flora of the Pines

- Bibliography

- About the Author