- 115 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

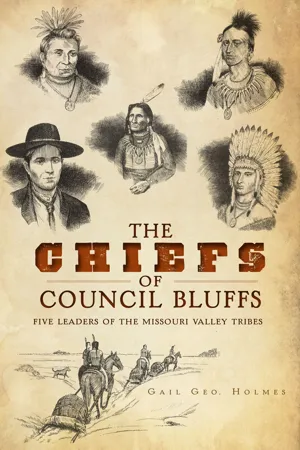

About this book

A look into the lives of five indigenous American tribal chiefs who lead their people as European settlers traveled into the region.

Two centuries ago, the fierce winds of change were sweeping through the Middle Missouri Valley. French, Spanish and then American traders and settlers had begun pouring in. In the midst of this time of tumult and transition, five chiefs rose up to lead their peoples: Omaha Chief Big Elk, the Pottawatamie/Ottawa/Chippewa Tribe's Captain Billy Caldwell, Ioway Chief Wangewaha (called Hard Heart), Pawnee Brave Petalesharo and Ponca Chief Standing Bear. Historian Gail Holmes tells the story of their leadership as the land was redefined beneath them.Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Chiefs of Council Bluffs by Gail Geo. Holmes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

FIVE LED THROUGH WINDS OF CHANGE

Five Native American leaders, two centuries ago in the Middle Missouri Valley, led their people through fierce winds of change. They were Omaha chief Big Elk; Pottawatamie/Ottawa/Chippewa tribe’s Captain Billy Caldwell; Ioway chief Wange Waha (called Hard Heart); Pawnee brave Petalesharo; and Ponca chief Standing Bear.

White people were filtering into and through their lands in ever-greater numbers. Occasional French (1707–1763) and Spanish (1763–1803) traders bartered guns, cloth, blankets, beads, bells and mirrors to Native Americans for furs. Americans (1804 and on) not only often traded for furs but also increasingly traveled through, poached and/or settled on Indian lands.

Neither the French government nor the Spanish government took much note of what their people did or what happened to them in the Missouri Valley. Some of those early isolated travelers were robbed. A few, caught in the paths of war parties, were severely beaten and robbed, kidnapped or killed.

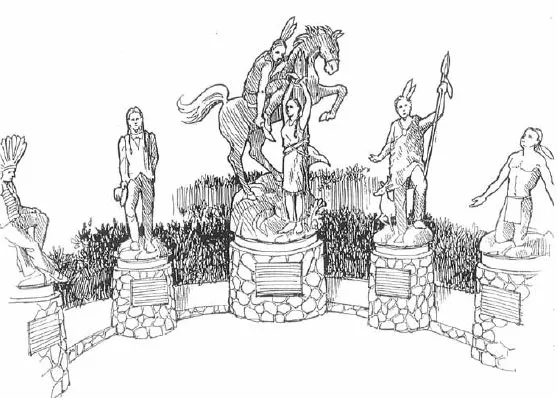

Picture of five sculptures of Indian chiefs.

JEFFERSON STUDIED THE AMERICAN WEST

President Thomas Jefferson, American student of government, history and science, demonstrated what President Abraham Lincoln later profoundly characterized as “government of the people, by the people, for the people.” Jefferson learned what had stopped French dreams and Spanish attempts to reach the Pacific Northwest by way of the Missouri and Columbia Rivers. Records showed they were blocked mostly by trade-controlling Teton Sioux in central South Dakota.

In 1804, Jefferson sent a carefully blended military-diplomatic-scientific team of forty well-armed men up the Missouri River. This Corps of Discovery under Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark was so well armed that Indians could not stop it. Yet it was so well equipped with gifts and so well schooled in the need for long-term good relations that the Native Americans almost always trusted it.

Lewis and Clark explained, as best they could, the change from Spanish to American in white government. They observed, listened, mapped, kept careful notes and took samples of new plants and animals they saw along the way.

This same American government later provided military protection to both whites and visiting Indian delegations. Roads, bridges and steamboat landings were built at government expense. American officials were more attentive to the needs of whites on the frontier.

At the same time, government officials hired farmers, blacksmiths and millwrights to serve some needs of the Indians. Congress voted monies to provide teachers for Indian youths. When the administration came back to Congress in 1821 saying that it didn’t know how to spend the money, Congress declared that churches should administer the funds in their work with Native Americans. Then missionary teachers began to fan out to and beyond the Missouri River, teaching native students how to plant and harvest crops on a much greater scale than they had been doing. They were taught how to design and sew, read and write and to calculate. Remember, those were the days when most Americans were still imbued with the revolutionary spirit that all must learn to blend and work together for the common good.

In fact, the American government established a “factory system” of fur trade stores, benefiting the Indians, but Congress failed to provide sufficient funds to extend them to all tribes. And private traders, contrary to law, provided alcohol to Indian customers, which factory stores could not do. Private traders offered credit, knowing the government would pay them if the Indians did not. But the factory stores could not extend credit. Private traders, also against the law in some areas, went out to buy furs while Indians were still hunting. Government factory stores were obliged to wait for the Indians to come to them with furs to sell. The factory system stores, out-maneuvered, finally shut down.

DRAGOONS CHASED POACHERS

Friction occurred between Native Americans and whites on the frontier. United States dragoons—mounted infantry—were organized in 1832, at Fort Leavenworth in Kansas Territory, north-northwest of today’s Kansas City, to protect against Indian attacks. As it turned out, however, the dragoons spent much of their time enforcing peace between separate Native American tribes and chasing white poachers off Indian lands.

As whites increasingly moved into and through Indian hunting lands, Native American leaders wrestled with changes sweeping through tribal lands, life patterns and customs. Dugouts, canoes, keelboats, swift-gliding downstream Mackinaws, smoke-belching steamboats and great billowing covered-wagon trains shocked the Indians. The wagon trains, especially, kicked up clouds of dust and frightened off the game animals on which the natives lived. Bison, deer, elk and other animals fled to quieter, less trafficked areas.

Transatlantic wars always affected trade. Native leaders usually felt they must side with those countries whose traders sold locally. Tribes fought alongside white men as long as their trade supplies continued to flow. But which side would win? That was the question. Natives, through hard experience, learned to carefully ponder which white government—French, English, Spanish or American—was most likely to triumph in war. There were benefits to being on the winning side.

Much more importantly, great losses of hunting lands surely would come with being on the losing side in transatlantic wars. The American government created more confusion by presenting medals and paper certificates declaring certain Indians, not previously recognized as such by their tribes, as chiefs. Sometimes these outside selections of “chiefs” were based on recommendations by Indian traders.

In such whirlwinds of change, there must have been many somber Indian conversations and councils. Of such, there is almost no record. There must have been many native leaders who spoke words of wisdom and wise council.

Under these circumstances, it is perhaps presumptuous of us to name only five native leaders as unusually exemplary. But reading from examples and from results, Big Elk, Billy Caldwell, Wange Waha, Petalesharo and Standing Bear certainly deserve to be held in honored remembrance. How many others are equally deserving, we do not know. But these five Native Americans are overdue recognition as great Americans who led their people through times of profound and troubling changes for these original landholders.

CHAPTER 2

OMAHA CHIEF BIG ELK

There were three Omaha chiefs in succession named Big Elk. They were great enough to be called principal chiefs of the tribe. The last of the Big Elk chiefs, however, was recognized as great far beyond his own tribe, including in Washington, D.C. Asked to speak at funerals of Native Americans outside his own tribe, Big Elk spoke not only with compassion but also with eloquence.

At the June 14, 1815 funeral of Indian leader Black Buffalo, Big Elk said: “Do not grieve. Misfortunes will happen to the wisest and best of men. Death will come and always out of season. It is the command of the Great Spirit, and all the nations and people must obey. What is past and cannot be prevented should not be grieved for. Misfortunes do not flourish particularly in our path. They grow everywhere.”

Like all men, Big Elk could be wrong at times. Speaking to Major Stephen H. Long, leader of the 1819–20 United States Scientific Expedition, about fifteen miles north of where Omaha is today, he said:

All my nation loves the whites and always have loved them. Some think, my Father, that you have brought all these soldiers [referring to about eight hundred soldiers of the Yellowstone Expedition, camped two miles farther north, under the command of Colonel Henry Atkinson at Missouri Cantonment] to take our lands from us, but I do not believe it. For although I am a poor simple Indian, I know this land will not suit your farmers. If I ever thought your hearts were bad enough to take this land, I would not fear it, as I know there is not enough wood on it for the use of the whites.

Omaha chief Ongpatonga/Big Elk.

Of course, neither Major Long nor Colonel Atkinson attempted to dispossess the Omaha tribe. That came in the form of a land sale in 1854 when steamboats easily brought in all the lumber whites needed to live there successfully.

BIG ELK FORESAW SWEEPING CHANGE

According to Alice C. Fletcher and Francis La Flesche in The Omaha Tribe, after a visit to Washington, D.C., Big Elk told his tribe:

My chiefs, braves and young men, I have just returned from a visit to a far-off country toward the rising sun, and have seen many strange things. I bring to you news which saddens my heart to think of. There is a coming flood which will soon reach us, and I advise you to prepare for it. Soon the animals which Wakonda has given us for sustenance will disappear beneath this flood to return no more, and it will be very hard for you. Look at me; you see I am advanced in age; I am near the grave. I can no longer think for you and lead you as in my younger days. You must think for yourselves what will be best for your welfare. I tell you this that you may be prepared for the coming change. You may not know my meaning. Many of you are old, as I am, and by the time the change comes we may be lying peacefully in our graves; but these young men will remain to suffer. Speak kindly to one another; do what you can to help each other; even in the troubles with the coming tide. Now, my people, this is all I have to say. Bear these words in mind, and when the time comes, think of what I have said.

Big Elk, burdened with age and almost blind, chided the Mormons in an August 28, 1846 conference at Cutler’s Park about rent for their use of the land near what now is the junction of Young Street and Mormon Bridge Road in northeast Omaha: “Do not cut down all the tall trees or I will be the only old tree left here.”

He then added, according to Andrew Jensen’s Journal of Manuscripts, August 28–29, 1856:

We heard you were a good people; we are glad to have you come and keep a store where we can buy things cheap. You can stay with us while we hold these lands, but we expect to sell as our Grandfather [the American president] will buy. We will likely remove northward. While you are among us as brethren, we will be brethren to you. I like, my son [referring to Brigham Young], what you have said very well; it could be said no better by anybody.

Reliable sources have said Big Elk died in 1848, 1849 or 1853. We don’t know, but his peaceful guidance of the Omaha tribe avoided bloodshed and gained his people the right to return to and always remain in their beloved, if adopted, homelands of northeastern Nebraska.

CHAPTER 3

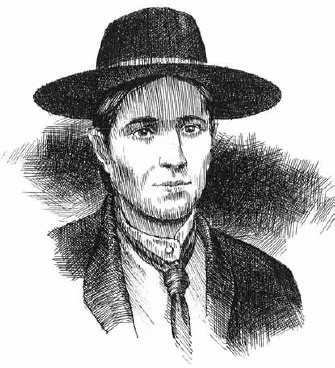

POTTAWATAMIE/OTTAWA/CHIPPEWA LEADER CAPTAIN BILLY CALDWELL

Before the days of professional résumés, Pottawatamie/Ottawa/Chippewa leader Captain Billy Caldwell easily outclassed most white officials of his day. Born in Canada in 1778 to British lieutenant colonel William Caldwell and a Mohawk mother, Billy, or Tequitoh (Straight Tree), was schooled by Jesuits in Detroit. His Indian friends called him Sauganash (Englishman). He was interested in history and adept in languages. English and Mohawk were his native tongues. He also learned French, several other Indian languages and some separate dialects. Billy was taken at age seven or eight to live with his father and new stepmother, who was a Pottawatamie.

INDIANS FOUGHT FOR HOMELAND

The Pottawatamie had fought valiantly, even brilliantly, against the Americans in the American Revolution. As the War of 1812 approached, they prepared to fight with the British again, this time with an eye to winning a homeland in the Great Lakes area between the British in the north and the Americans in the east.

Lieutenant Colonel William Caldwell and his son, Billy, sided with the Pottawatamie and the British. When the fighting broke out, Billy performed so well and valiantly that he was commissioned a captain in the British Indian Service.

Pottawatamie/Ottawa/Chippewa leader Captain Billy Caldwell.

Some American soldiers captured by British troops were turned over to the Pottawatamie to be returned to their homes in Illinois and Indiana. Some of those prisoners were killed and others tortured by the Pottawatamie, but a few escaped to tell the story. A new American drive into Canada later defeated the British.

After the war, Colonel Caldwell was appointed superintendent of Canada’s Western Department of Indian Affairs. Captain Billy Caldwell was named assistant to his father. Billy succeeded his father and then later also was let go.

He drifted south of the American border and engaged in fur trade. Captain Billy joined the Forsythe fur trade house in Chicago and became a busy and important Forsythe trader.

Because of his language skills, Captain Billy was called upon to serve as interpreter for government officials in the Chicago area. In recognition for his good service, he was appointed in 1826 a justice of the peace. That was in addition to his fur trade and his interpretive services.

The American government, still chafing from the Pottawatamie killing of American prisoners turned over to them by the British, rebuilt its forts in the then upper northwest. The old wartime allies, the Pottawatamie/Ottawa/Chippewa, were then told they would be moved west across the Mississippi River, away from British influence. The Pottawatamie, without tribal chiefs, were governed by okmulgee, or village leaders.

Hearing the American ultimatum, one-third of the Pottawatamie (far outnumbering the Ottawa and Chippewa banded with them) fled into Canada, east of the Great Lakes, where their descendants remain today. About a third of the Pottawatamie and their Ottawa/Chippewa allies quickly agreed in the early 1820s to sell their village lands to the American government and move to northeastern Kansas.

The final third enlisted fur trader Billy Caldwell to represent them at the Chicago Peace Treaty negotiations. A g...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- 1. Five Led Through Winds of Change

- 2. Omaha Chief Big Elk

- 3. Pottawatamie/Ottawa/Chippewa Leader Captain Billy Caldwell

- 4. Chief Hard Heart Quit His Ioway Tribe Favoring the British in the War of 1812

- 5. Petalesharo Broke Pawnee Tradition of Human Sacrifice

- 6. Standing Bear Won Change in American Law for Indians

- 7. American Policies in the New Republic

- 8. Jackson’s Indian Removal Plan

- 9. Ancient Tribal Groups Also Migrated

- 10. Politicians Moved Native American Tribes Around

- 11. End of Indian Sovereignty in the Valley Foreseen

- 12. Mormons Built on Both Sides of Mid-Missouri River

- 13. Indians Demanded Rent from the Mormons

- About the Author