- 211 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Canoe Indians of Down East Maine

About this book

The story of those who inhabited coastal Maine thousands of years before the French arrived, and how their lives changed at the dawn of the seventeenth century.

In 1604, when Frenchmen landed on Saint Croix Island, they were far from the first people to walk along its shores. For thousands of years, Etchemins—whose descendants were members of the Wabanaki Confederacy—had lived, loved and labored in Down East Maine. Bound together with neighboring people, all of whom relied heavily on canoes for transportation, trade, and survival, each group still maintained its own unique cultures and customs.

After the French arrived, though, these indigenous people faced unspeakable hardships, from "the Great Dying," when disease killed up to ninety percent of coastal populations, to centuries of discrimination. Yet they never abandoned Ketakamigwa, their homeland. In this book, anthropologist William Haviland relates the challenging history endured by the natives of the Down East coast and how they have maintained their way of life over the past four hundred years.

Includes illustrations

In 1604, when Frenchmen landed on Saint Croix Island, they were far from the first people to walk along its shores. For thousands of years, Etchemins—whose descendants were members of the Wabanaki Confederacy—had lived, loved and labored in Down East Maine. Bound together with neighboring people, all of whom relied heavily on canoes for transportation, trade, and survival, each group still maintained its own unique cultures and customs.

After the French arrived, though, these indigenous people faced unspeakable hardships, from "the Great Dying," when disease killed up to ninety percent of coastal populations, to centuries of discrimination. Yet they never abandoned Ketakamigwa, their homeland. In this book, anthropologist William Haviland relates the challenging history endured by the natives of the Down East coast and how they have maintained their way of life over the past four hundred years.

Includes illustrations

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Canoe Indians of Down East Maine by William A Haviland in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Archaeological Background

Although there is general agreement that the ancestors of the historic Etchemins have been living along the coast for something like 3,000 years, not all scholars agree that people living here before that are ancestral to more recent populations. Some think that there was a population replacement about 3,800 years ago, but many others are skeptical. I belong to the latter group, and today’s Wabanakis also see themselves as having been in place since the beginning. But more about this later.

Written records pertaining to the Gulf of Maine’s original inhabitants are almost nonexistent before 1604, so to learn about earlier history, we must turn to archaeology for information. Along the coast, numerous shell middens were formed as refuse was discarded by people in the course of their daily activities. Although these middens have suffered in varying degrees from the effects of erosion caused by rising sea levels, until the past few decades, they were little disturbed by development or the activities of relic collectors. Therefore, they preserve a record of people’s past activities over the many millennia before the advent of written records. This record is retrievable, however, only through careful and meticulous excavation, usually by professionally trained archaeologists. The good news is that many sites along the coast, both on islands and the nearby mainland, have been professionally excavated; the bad news is that many hitherto untouched sites have been disturbed in recent decades by untrained diggers, with a consequent loss of irreplaceable information.

In addition to the shell middens, archaeologists have also investigated a number of interior sites, often near the falls of rivers and streams where people fished and portaged their canoes or at other good fishing spots. Though it may seem that archaeologists are merely digging up things, what they are really digging up is information. That information comes not from recovered potsherds, spear points and other artifacts by themselves, but rather from the way these objects are associated with one another, as well as with other things such as charcoal, fire-cracked rock, plant, fish and animal remains and so forth. Once taken out of context, objects by themselves tell us next to nothing. Thus, to dig around in archaeological sites looking for relics destroys them, and the information they contain, as effectively as if they were bulldozed into oblivion.

PALEO-INDIANS

Archaeology has revealed that the first people to arrive in the Northeast did so at a time of far-reaching environmental change. Up until eighteen thousand years ago, the region was buried beneath ice more than a mile thick that extended east to the edge of the continental shelf and as far south as Long Island Sound. But then, in response to climatic warming, this glacier began to melt away, receding northward over the next several millennia. By twelve thousand years ago, the edge of the ice had receded north of the Saint Lawrence River, allowing vegetation to spread into the region. First came plants at home in tundra-like conditions, but as warming continued, plant communities continued to change; gradually, trees such as spruce and fir began to take hold, augmented by birch, alder and some other hardwood species over time.

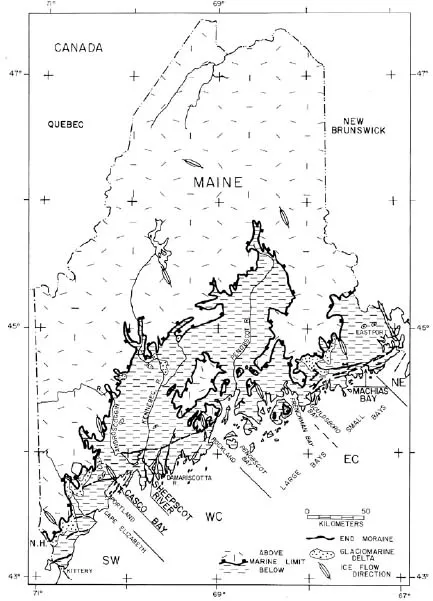

As the glaciers continued to melt, huge amounts of water were released into the seas. Meanwhile, the land, which had been greatly depressed by the weight of the ice, began to rebound (much as the surface of a sponge will rebound if a weight is removed from it). There was, however, a lag between removal of the weight and uplift of the land; hence, the waters rose faster than the land at first. As a consequence, by about twelve thousand years ago, salt water had flooded the coastal lowlands and river valleys, extending as far as one hundred kilometers inland from the present coastline. In the Penobscot and Kennebec Valleys, for example, seawater reached as far north as Medway and Bingham, respectively. In short, anything below about 120 meters elevation today was under water!

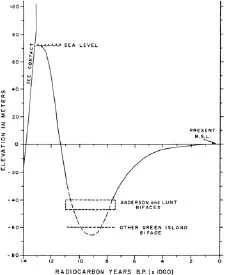

Because the rate of crustal uplift ultimately caught up with and surpassed the rate of sea level rise, by ten thousand years ago, water levels had fallen as many as sixty meters below where they are today. This exposed a great deal of land and put shorelines up to twenty kilometers southeast of their present location. At that point, rates of sea-level rise and crustal uplift again reversed, and salt water began once again to drown low-lying areas. Although this rise was rapid at first, it decreased over time until, fairly recently, it began to increase again.

This map shows the extent of flooding in Maine when sea levels (shown in dark) were at their height some twelve thousand years ago. Courtesy Dan Belknap.

This graph shows how sea levels have risen and fallen in the Gulf of Maine over the past fourteen thousand years. The “Anderson biface” is illustrated below. Courtesy of the late James Peterson.

During this period of striking environmental change, evidently by 11,500 years ago, the first people began to drift into Maine and Canada’s Maritime Provinces. This happened probably not as a deliberate migration, but rather gradually, as population growth in regions to the south nudged people into empty areas in the north. At the same time, populations adapted to particular environments would have been pulled northward in response to climatic warming and the consequent shift of vegetation zones. These first people, whom archaeologists call Paleo-Indians, were hunters of big game, including caribou, mammoths and mastodons. All were available here 11,000 years ago. They hunted smaller animals, as well, including arctic fox and beaver.

On the coast, they may also have preyed on the bearded seals and walrus that were present. They, no doubt, had some kind of watercraft, as evidence from Vermont suggests that Paleo-Indians were exploiting the resources of the saltwater sea that filled the Champlain Basin when sea levels were at their height. And, like all known hunting people, they no doubt gathered both edible and medicinal plants as these were seasonally available.

Although a number of Paleo-Indian sites have been investigated in Maine and the Canadian Maritimes, not to mention New Hampshire, Vermont and Massachusetts, none has been found on the immediate coast. However, isolated Paleo-Indian spear points have been picked up at such places as Arrowsic, Boothbay and Mount Desert. These so-called fluted points are highly distinctive; the fluting was accomplished by removing, from the base, long flakes running about halfway up each face of the point. This thinned area could be inserted easily into the notched end of a wooden shaft for secure hafting. The design was perfectly suited for easy penetration of the hide and flesh of animals both large and small.

An assortment of Paleo-Indian tools from Maine. In the top row and middle row left are the distinctive fluted points. The other tools were for cutting, scraping and woodworking. Courtesy Arthur Spiess, Maine Historic Preservation Commission.

Besides these spear points, Paleo-Indian sites include a variety of sharp stone knives and flakes for cutting meat, scrapers for processing hides into clothing, bedding and bags and gravers and scrapers for working both wood and bone. Although they used stone from sources in Maine, such as rhyolite (silica-rich stone of volcanic origin) from Mount Kineo on Moosehead Lake and chert (silica-rich crystalline sedimentary stone) from around Munsungan Lake north of Mount Katahdin, not to mention the Canadian Maritimes, they also made use of stone from such faraway places as Mount Jasper in New Hampshire, the Champlain Basin of Vermont, western New York, Pennsylvania and even Ramah Bay in northern Labrador. Clearly, these people had far-ranging contacts. Such objects no doubt had special significance, not just on account of their foreign origin, but also because of their distinctive colors and history of how they came into the possession of the person who used them. They served to connect the user with the wider physical and mythological world in which he or she lived.

An idea of what life in a Paleo-Indian camp might have been like. Collection of the author.

With few exceptions, Paleo-Indian sites are small and were occupied briefly (but often repeatedly) by small groups of people, perhaps one or two families together. Representative is the Michaud Site, located by the Lewiston-Auburn airport. Here, on sandy soil next to what was once a swamp—a favorite kind of campsite—eight or nine clusters of artifacts were left where people put up their shelters and carried out various activities. Three such spots, for example, are the remains of a shelter on either side of which were outside activity areas. In one of these, points were manufactured and replaced in refurbished bone or wooden hafts. In the other, game was processed and hides were transformed into such things as clothing, bedding and bags.

Periodically, the small groups of Paleo-Indians would come together in larger encampments, as at the famous Bull Brook site near Ipswich, Massachusetts, where they gathered for a communal caribou hunt and to trade, find marriage partners and socialize. Clearly, they were a highly mobile people, but we should not think of them as rootless wanderers. To survive exclusively by foraging for wild foods, people must have detailed knowledge of a region—the kind of knowledge that comes only from lifelong familiarity. Moreover, it is clear that they returned repeatedly to particular favored spots. Their home territories may have been large, but like all historically known hunting and gathering people, they no doubt felt a deep sense of connection with their homelands.

THE ARCHAIC PERIOD

By eight thousand years ago, the climate had warmed to the point that the woodlands of Maine and New Brunswick began to take on something of the characteristics of the mixed deciduous-coniferous forests with which we are familiar today. As a consequence, the arctic and sub-arctic animals that Paleo-Indians hunted had either moved north (like the caribou) or became extinct (like the mammoths). In the new forests, deer, moose and a variety of small animals became abundant, and a wide range of plant foods were available for several months of the year. Various kinds of fish, too, became abundant in bodies of both fresh and salt water. As people adjusted to these new conditions, they developed different practices tailored to interior and coastal living. These changes usher in what archaeologists refer to as the Archaic Period, which dates between roughly nine thousand and three thousand years ago.

The earliest archaeological material of this period that we have from the coast comes from sites that are now submerged beneath forty or more meters of water. One such site is near a now-submerged channel of the Union River in Blue Hill Bay, southwest of Mount Desert Island. Here, in the 1990s, scallopers dragged up stone tools like the 8,000-year-old biface illustrated above. Investigators later discovered a nearby lake (also drowned), formed during a slow period of sea level rise between 11,500 and 8,000 years ago. The landscape would have been an attractive one to people living off fish, game and wild plants.

The “Anderson biface,” one of the eight-thousand-year-old bifaces dragged up in Blue Hill Bay by scallopers. This may have been a preform intended to be finished off into a spear or knifepoint. By this time, points were no longer fluted but completed by fine, parallel flaking. Courtesy John Crock.

Another early site, this one not submerged, is at Dresden Falls (which are now submerged) on the Kennebec River. Although the site’s existence has been known for a quarter of a century, only recently has its true significance become apparent. Preliminary investigation has revealed that here was a village covering somewhere around twenty acres that was occupied seasonally between about 9,000 and 4,500 years ago. There are only two other similar sites of this period in all of New England. Garbage pits and intact hearths have preserved a variety of plant, fish and animal remains, including sturgeon, striped bass, salmon, muskrat, turtles and moose or deer. Stone projectile points, pieces of whetstones, gouges, adzes, axes, scrapers and slate knives have also been found. Though the site awaits a more thorough investigation, it is now protected by the Archaeological Conservancy, with the help of funds from Land for Maine’s Future and the Friends of Merrymeeting Bay.

Limited though our present knowledge is, it appears that people who spent much of the time moving about between small campsites gathered here to catch migrating fish on their annual runs. At the time, sea levels were lower than today, and the first falls of the Kennebec were located between Swan Island and Dresden. As yet, there was no channel on the other side of the island; not until about five thousand years ago were sea levels high enough to drown the falls and create the second channel. It was the perfect place to catch the fish; their abundance, large size and predictability allowed such a large gathering there.

A noteworthy observation is that styles of projectile points at this site are similar to those found at sites west of the Kennebec but are unlike those farther east, suggesting the presence of an ancient ethnic boundary. What makes this intriguing is that this was later the border between Etchemins and Abenakis. The possibility is that this ethnic boundary is quite ancient. To the east of the boundary up into New Brunswick, stone projectile points are not particularly distinctive, nor are they common. It may be that heavier reliance on resources in coastal waters favored use of nets, traps and spears tipped with bone.

Another site of the same vintage as Dresden Falls that has been intensively investigated is on Meddybemps Lake at its outlet, the Dennys River. From here, there was easy access to the Saint Croix River and Passamaquoddy Bay, not to mention the waterways of interior Maine and New Brunswick. People first camped here around 8,600 years ago, living in circular shelters dug into the ground, with a pole framework covered with bark or hide. From their encampment, they exploited the alewife spawning runs; fished for perch, suckers and eels; and hunted or trapped a variety of mammals, birds and turtles. They also gathered various seeds, nuts and other plants. The quantity of food remains, as well as the presence of storage pits, shows that people were not just living day to day but also planning for the seasons ahead. Occupied seasonally between the spring alewife run until fall, this place was visited repeatedly over a period of 400 years or so.

Four artifacts from the now-submerged Lazygut Island site. On the left: two bifacially flaked tools of red mudstone, one with a highly polished end. On the right top: ground slate ulu, and below it a ground stone adze. Slate knife fragments from Dresden Falls are from tools like this ulu and were probably used to process fish. Courtesy Steven Cox.

Moving forward in time, another submerged site off Deer Isle in Penobscot Bay, near the Lazygut Islands, dates to the Middle Archaic Period, around 6,100 years ago. At the time, sea levels were still eight meters below where they are now. Thus, what today is sea bottom was then a broad mudflat behind a granite headland. The location was a good one, with a well-drained spot for a shelter, abundant shellfish nearby and access to the open sea. From this site, scallop draggers, as well as divers from the Maine State Museum, have recovered large, worked oyster shells; a semi-lunar knife, or ulu (the term used by the Inuit for similar knives), made of slate; a rhyolite “preform” (stone that has been flaked but had not yet been finished to produce a specific tool); and other implements. Two ground ulus and a full channel gouge have also been pulled up from drowned sites in Passamaquoddy Bay.

The ground slate ulus just mentioned, along with fragments of similar implements from the Dresden Falls site, are representative of technology new in the Archaic Period. Although people continued to make flaked stone tools, ground slate cutting tools were superior for processing the soft flesh of fish as they were split for drying. The smooth edge of the slate knife does not tear the meat the way the nicked edge of a flaked chert knife will. Ground slate also does a better job of scraping the hides of marine mammals, which are more...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. The Archaeological Background

- 2. Life in Etchemin Country at the Dawn of Recorded History

- 3. Defending the Homeland

- 4. Survival and Renewal in an Alien World

- Bibliography

- About the Author