![]()

Part I

Four Warships from Three Centuries

The warships that are discussed in this part include two that were enemy vessels and two that were American. The sinkings span four of the wars in which the United States was involved, starting with the American Revolution and running through World War II. HMS Albany was a British sloop of war that sank in 1782. USS Adams was an American sloop that was burned in the middle of the War of 1812. CSS Georgia was a Confederate raider made in England that sank following the Civil War. USS Eagle 56 was a submarine chaser built at the end of World War I that was used throughout World War II. Significantly, it was the last American warship to be sunk by a German submarine, in 1945.

LOST CANNONS: THE WRECK OF HMS ALBANY

The Northern Triangles are an extensive series of ledges located at the southern entrance to Penobscot Bay. Even in the twenty-first century, sailors passing through Two Bush Channel need to beware of getting off course for fear of running into a large minefield of rocks, most of which lie just below the ocean’s surface at low tide.

Captain John Flint, who lives in Cushing, Maine, has researched a number of Penobscot Bay shipwrecks, including the wreck of HMS Albany. One day, his friend Richard Spear told him the story of the wreck of Albany and where the remains of the ship were located. Flint passed the information along to two local fishermen, who, after trolling the ledges of Northern Triangles, found two cannons lodged in the crevasses of some rocks that were barely visible at low tide.

John Flint is a retired sea captain who has researched a number of Penobscot Bay shipwrecks. Author’s collection.

The Northern Triangles are barely visible at low tide. Little Green Island is seen in background. Author’s collection.

The fishermen hauled the cannons into their boat, took them home and informed the state archaeological authorities of their discovery. Word came back from the state that they had no right to take the cannons, or any other parts of the ship they had found, and to put everything back. The fishermen dutifully told state authorities that they had done so. Exactly where the cannons lie today, however, remains a mystery.

This is the story of HMS Albany and of how the ship ran on the Northern Triangles during a winter storm in the last days of the American Revolution.

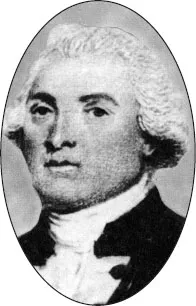

Henry Mowat

At the start of the American Revolution, Henry Mowat (1734–1798) was a frustrated British naval officer who had spent nearly twenty years of what would be a forty-three-year career patrolling the North American coast. Mowat, who was probably more familiar with the New England coast than any other British naval officer, first came to North America in 1758 as a twenty-four-year-old. As the years passed, he was promised “improved commands,” but for reasons that will be explained, promotions were slow in coming.

Mowat came from good seafaring stock. Some say that one of his ancestors was a survivor of the Spanish Armada who ended up in northern Scotland in 1590. Young Henry grew up on the wind-swept Orkney Islands. His father, Captain Patrick Mowat, commanded a ship on Captain James Cook’s first global voyage in the 1760s, and his three brothers were also navy men.

At the conclusion of the French and Indian War in 1763, Mowat was ordered to guard a survey expedition for the official cartographer of King George III. For the next twelve years, Mowat guided royal survey ships along the Atlantic coast from Newfoundland to the Virginias. Most of this time, he was skipper of Canceaux. As relations with American colonies worsened in the early 1770s, the Canceaux was converted from a three-masted merchant ship into an armed vessel.

Wesleyan Professor James Stone wrote that by the start of the American Revolution, “[Mowat’s] many years on the survey of the coast to the eastward of Boston and his knowledge of all the harbors, bays and creeks and shoals resulted in his being the most knowledgeable and experienced naval commander in British North America, bar none.”

Henry Mowat was a British naval officer who spent twelve years surveying the New England coast and the St. Lawrence River before the American Revolution. Courtesy of Maine Historical Society/Maine Memory Network.

Following the Battles of Lexington and Concord, rebel forces captured Henry Mowat near Falmouth (present-day Portland) on May 7, 1775. He was released, having given his word of honor to his captors that he would return the next morning. Mowat broke his parole, however, and fled in his ship Canceaux to Boston.

British admiral Samuel Graves, commander of the North American Station, had been given an impossible task. At the start of the Revolution, his assignment was to oversee a blockade of the entire American coast with a mere thirty ships. Poor Graves was in over his head and was unable to stop the harassment of British ships that went on in the months and years that followed.

Graves’s orders came from First Lord of the Admiralty John Montagu, Earl of Sandwich: “Exert yourself to the utmost towards crushing the daring rebellion.” Graves accordingly directed Henry Mowat to “proceed along the coast and lay waste, burn and destroy such seaport towns as are accessible to His Majesty’s ships…to make the most vigorous efforts to burn the towns and destroy the shipping.” Graves added that it was up to Mowat to go wherever he wanted.

Mowat arrived in Casco Bay on the evening of October 16, 1775, in command of three small warships and proceeded to disobey Admiral Graves’s orders. The next morning, he sent a barge to Falmouth with a letter to the town fathers stating that he had orders to fire on the town immediately. Mowat added that he would “deviate from his orders” and give the townspeople two hours to evacuate the next morning. Captain Mowat emphasized that his orders could not be changed and that he was already risking the loss of his commission by giving the town a warning. It turned out to be a decision that would haunt him for the rest of his career.

It took Mowat most of October 17 to get his ships into position, and on the morning of October 18, he then waited an additional half hour before beginning to bombard Falmouth. At 3:00 p.m., he then sent landing parties ashore to set fire to buildings not demolished by gunfire. It is estimated that more than four hundred structures were destroyed, leaving most of the town homeless.

Professor Stone wrote, “Mowat’s name would go down in infamy.” Nearly 130 years later, Portland journalist C.E. Banks compared Mowat to Nero: “His unparalleled barbarity was exploited abroad and his name finally consigned to that limbo of hopeless condemnation where he will be remembered by future generations as a fiend and not as a man.”

There are those who consider Mowat a “war criminal” for ordering the destruction of Falmouth in October 1775. George Washington would later write of his action, “I know not how to detest it.” While American revolutionaries saw him as a destroyer, Loyalists considered him the heroic savior of Fort George and the town of Castine. Although Mowat would prove to be the indispensible man in the defense of Castine in 1779, his name would be forever tarnished by the notoriety he received as the destroyer of Falmouth, as well as for having broken his parole.

His name was also not respected as a British naval officer. From the military perspective, he was seen as disobeying Graves’s orders by warning the town of his imminent attack. The result was that for the rest of his career, promotions were slow in coming to Mowat, leaving him an embittered man.

Following the destruction of Falmouth, Mowat requested and was given command of HMS Albany, which was purchased by the Royal Navy in 1776. In his research into the sinking of Albany, Captain John Flint thought that the ship was probably the former American sloop Howe. Albany was wider and newer than Mowat’s decrepit old Canceaux. Although far from an ideal vessel, Mowat considered it an improvement over his previous command.

The British purchased American-built sloops like Albany in great numbers during the American Revolution, but their shallow drafts and poor accommodations for officers and crew made them less than appealing to captains. Mowat considered Albany seaworthy, although in poor condition.

Henry Mowat would command HMS Albany for the next six years. His ship was a 230-ton sloop of war. It was ninety-one feet long with a twenty-six-foot beam and was armed with sixteen cannons. At the time of the Penobscot Expedition in 1779, Albany carried a crew of 125 men, although at the time of its fatal accident in 1782, the ship’s crew was fewer than sixty men.

HMS Albany was ninety-one feet long and was built in New York. It is thought that Albany was converted to a warship from the American sloop Howe. Courtesy of John Flint.

For the next four years, the now-infamous captain prowled the New England coast in his refitted sloop of war, preying on American merchant shipping. After the British evacuation from Boston, he took prizes and protected the sea lanes between New York and Halifax. Captain Flint wrote, “Most of the time Albany guarded Canadian waters from rebel fishermen, an assignment he found demeaning for one of his seniority and talents.”

Although Mowat was described as haughty and having an explosive temper, he was respected by his peers as a good officer. Admiral Shuldham, who replaced Admiral Graves, referred to Mowat as “the most useful person in America under naval authority.” A London newspaper hailed his patrol as “the most successful of the fall [1777] season.” While on patrol, Mowat had twice confronted John Paul Jones. On the second occasion, he drove the legendary American captain into Boston Harbor after putting his ship Alfred out of action.

Life on HMS Albany, as on all ships in the Royal Navy, was brutal and hard. On board a small sloop of war patrolling the Maine coast, it was doubly so. The quarters were cramped, with more than one hundred officers and men crowded into dank and dark spaces between the decks.

The Maine winters were especially difficult, with northeast gales, blizzards and the pressure of constant patrolling. The coast was uncharted except for sketches that Mowat had personally made on his many cruises since 1754. It was therefore not unusual for Albany to run on unmarked rocks. Mowat would then be forced to seek a sheltered cove, haul his sloop out and have the ship’s carpenter make the necessary repairs.

Summers were more bearable. Provisions could be purchased from sympathetic Loyalist farmers, and fresh water was available from the many streams along the coast, as well as wood for the galley range. Hatch covers could be removed, allowing air and sunlight to penetrate below decks. Even Maine tides were helpful. Mowat would run Albany ashore at high tide, and when the tide dropped, the crew was put to work scraping away the barnacles and grass fouling the hull. Crew problems were rare since there were few places to run and hide along the lonely, rocky coast.

The Penobscot Expedition

A year into the Revolution, the Royal Navy was dominating the Atlantic seaboard. Over time, however, bad weather and battles with the French navy withered away what one naval historian has called “a vast armada, one of the largest fleet of warships ever seen in North American waters.” By 1779, not a single town in New England was in British hands.

The situation was particularly serious at the New York and Halifax dockyards, the only towns where British ships could be refitted. At Halifax, Nova Scotia, Albany’s homeport, things were so bad that the effectiveness of the North American Squadron was threatened. Supplies for repair were running low, especially timbers for masts, bowsprits and planking.

Under these deteriorating circumstances, Henry Mowat received orders in 1779 for his first major command since the burning of Falmouth in 1775. He was given a three-ship flotilla with orders to transport elements of two Highland regiments from Halifax to Penobscot Bay. There, he and British general Francis McLean were ordered to build a fort overlooking the entrance to the Penobscot River at present-day Castine. The purpose of the fort would be to secure vital naval stores and timber for the shipyards in New York and Halifax.

A British presence would thus be reestablished that would provide a haven for Loyalists in the region. The fort would also serve as a base for protecting Canadian commerce and fishing from American privateers. The orders pleased General McLean, who wrote, “He would derive much assistance from Mowat’s abilities and knowledge of that coast.”

Mowat arrived in Halifax on schedule to convoy the expedition. In June 1779, a fleet of three warships and four armed transports, carrying 650 Scots soldiers, set sail from Halifax, with Henry Mowat in command in his flagship Albany.

Led by General McLean, the soldiers disembarked on June 17, 1779, and took control of what at that point was a mere hamlet surrounded by several sawmills. A site for a fort was staked out on a commanding rise two hundred feet above sea level, and work was begun. The proposed fort would be named Fort George in honor of King George III.

Professor Stone pointed out that an added advantage was that most of the officers and men were Scots, who were well known for their engineering skills. Located above the village, Fort George was sited so that its guns had an open field of fire in any direction. In the words of George Washington, Fort George became “the most regularly constructed and best finished of any fortress in North America.”

Building Fort George turned out to be a race against time. When word of the British occupation of th...