- 225 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Tennessee's Thirteenth Union Cavalry was a unit composed mostly of amateur soldiers that eventually turned undisciplined boys into seasoned fighters. At the outbreak of the Civil War, East Tennessee was torn between its Unionist tendencies and the surrounding Confederacy. The result was the persecution of the "home Yankees" by Confederate sympathizers. Rather than quelling Unionist fervor, this oppression helped East Tennessee contribute an estimated thirty thousand troops to the North. Some of those troops joined the "Loyal Thirteenth" in Stoneman's raid and in pursuit of Confederate president Jefferson Davis. Join author Melanie Storie as she recounts the harrowing narrative of an often-overlooked piece of Civil War history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Dreaded Thirteenth Tennessee Union Cavalry by Melanie Storie in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

“A CIVIL WAR AMONG US”

In 1860, fourteen-year-old John G. Burchfield was living in Carter County in the small, rural community of Elizabethton, situated in upper East Tennessee. Like many young boys of the day, politics did not generally occupy his thoughts much. He was too busy helping on the family farm, fishing with his friends and working as a blacksmith’s apprentice. Yet little did he realize how much his life would change over the course of the next four years. Not only did young Burchfield become immersed within a Unionist protest movement, but he also became one of the young soldiers who later joined the Thirteenth Tennessee Volunteer Cavalry.

With the election of Abraham Lincoln in November 1860, seven states from the lower South passed ordinances of secession and formed the Confederate States of America. In February 1861, Tennessee governor Isham Harris and the state legislature called for a special referendum on whether to call a state convention to consider secession. Tennessee voters went to the polls on February 25 and rejected the call for a convention on secession by a margin of 69,357 to 56,535. In East Tennessee, the vote was much more lopsided, with 33,299 voting against a convention to 7,070 who favored holding one.16

Nevertheless, events quickly conspired to change the views of many Tennesseans on the issue of secession. On April 12, 1861, the first shots of the Civil War rang out over Fort Sumter in South Carolina’s Charleston Harbor, prompting President Lincoln a few days later to call on the states for seventy-five thousand volunteers. Interpreting this as a threat to the South, the Southern states of Virginia, Arkansas and North Carolina joined the Confederacy.17 Ironically, John Burchfield witnessed these events in Charleston, as he and his father had driven some hogs down from East Tennessee. As a young boy, he commented that he “was impressed with the portent of the storm.”18 The news of Fort Sumter and Lincoln’s call for troops to suppress the rebellion arrived in East Tennessee before the Burchfields returned. Having witnessed the events unfold in Charleston, young John became much more aware of the serious political climate. Therefore, the implications of Governor Harris’s response to President Lincoln’s call for volunteers were not lost on the young man or on the tens of thousands of Tennesseans. In a communication to the White House, Harris declared, “Tennessee will not furnish a single man for the purposes of coercion, but 50,000 if necessary, for the defense of our rights and those of our Southern brothers.”19

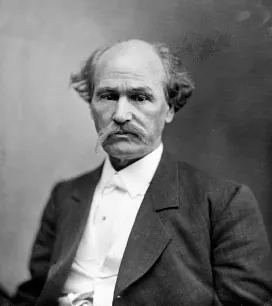

Isham Harris served as Tennessee’s governor from 1857 to 1862. A West Tennessean, Governor Harris was a staunch secessionist and successfully led the state out of the Union. Once the Union army gained control of Nashville in 1862, President Abraham Lincoln appointed Andrew Johnson as military governor of Tennessee. Harris spent the rest of the war as an aide to various Confederate generals. After the war, he fled to Mexico and then to England for a time before returning to Tennessee and being elected a U.S. senator in 1877. He held this position until his death in 1897. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

In the weeks that followed, both secessionists and Unionists launched intensive public speaking campaigns. Men such as Thomas A.R. Nelson, Connally Trigg, Horace Maynard, Andrew Johnson, Oliver Temple and John Baxter campaigned throughout East Tennessee giving speeches in favor of the Union. Notable men such as Landon C. Haynes, William H. Sneed, William Cocke, William G. Swan, Joseph B. Heiskell and others undertook support for the Confederacy in East Tennessee. In Elizabethton, a debate was planned between the two groups. A platform was placed near the courthouse, where Joseph Heiskell of Rogersville and William Cocke of Knoxville were billed to speak on behalf of secession. Reverend William B. Carter and Nathaniel G. Taylor, both from Carter County, were selected to defend Unionism. Reportedly, thousands from Carter and surrounding counties turned out for the public debate. From the beginning, however, the mood was contentious, with many in the audience carrying pistols. At one point, the debate became personal as the Carter family lineage was called into question. No doubt that caused an audible gasp, since the Carters were among the first settlers to the area and very influential. In fact, the county itself was named in honor of William Carter’s grandfather. Some in the audience were notably jumpy, as was made evident when a young lady tossed a bouquet of flowers onto the platform showing her appreciation for the speakers. Some men immediately jumped to their feet with pistols drawn. Nevertheless, the event concluded peacefully.20

About two weeks following the public debate in Elizabethton, David Kitzmiller, a Baptist minister and outspoken secessionist from Johnson County, penned a letter to Governor Harris. Writing on behalf of the county’s secessionist element, Kitzmiller sought to provide the governor with “some of the practical operations of Unionism” in the county. Complaining that the “conduct of the Union party is too intolerable to be borne,” Kitzmiller claimed Unionists were “threatening the lives of the secessionists” without reason. Estimating that Union men in Carter and Johnson Counties outnumbered secessionists at least nine to one, the reverend pleaded for protection from the governor, affirming, “Secessionists will have to leave here or submit, you have no idea what we have to endure.” Unionists, he claimed, were in direct communication with President Lincoln and were making plans to fight for the Union if the state seceded. The leading Unionist agitator, in Kitzmiller’s opinion, was Congressman Roderick Butler. Butler’s conduct, he wrote, “has not a parallel in the south,” as he constantly encouraged East Tennesseans to vote against secession. Kitzmiller openly worried that unless something changed there would be “a civil war among us here.” Fearful that Unionists might discover his letter, Kitzmiller wrote, “I will have to mail this letter in Virginia to keep down suspicion.”21

Many in upper East Tennessee received their mail and local news via stagecoach. On April 18, a stagecoach carrying the mail and a few passengers arrived in Johnson County, Tennessee, from Abingdon, Virginia, some thirty miles away. Two of the men on the stagecoach were from Virginia, and they checked into a Taylorsville hotel owned by Samuel Northington. That evening, the men caused a commotion in the street by shouting and waving a Confederate flag in loud celebration of the recent secession of Virginia. Northington, a Unionist, cautioned them that Tennessee had not seceded and many townspeople did not support the Southern Confederacy. The men took offense and replied they had a right to celebrate and furthermore did not care what Unionists thought. That evening, Northington, along with his son Hector and fellow Unionist Joseph Wagner, agreed they would take the flag, by force if necessary, if the men displayed it again. The next morning, as the Virginians emerged from their rooms, they prepared to ride through town waving the Confederate flag. As they mounted their horses, the three Unionists appeared with shotguns and demanded the flag be handed over. One of the men began to swear at the elder Northington and challenged him to try to take it. To that end, Northington began shooting several holes in the flag. Caught off guard, the men handed over what was left of the flag and quickly rode out of town.22 Realizing the seriousness of their position, the people of Johnson County on April 27 assembled at the courthouse to declare their “attachment for the Union and the Constitution of our Fathers.” Further, they contended there was no “just cause for a disruption of this government.” The resolutions asserted the people of Johnson County wanted to live in peace and were willing “to be passive spectators.” Other East Tennessee counties followed the same example with similar statements.23

In early May, Governor Harris called for a second referendum to gain approval of an “Ordinance of Secession.” After voters defeated a call for a secession convention earlier in the year, the governor sought to bypass the step altogether and put secession to a direct vote without a convention. In the meantime, Harris took steps that aligned Tennessee in a military league with the Confederacy. Outraged, Unionists called for their own convention to address what they labeled the governor’s unconstitutional and pro-secessionist actions. A two-day convention took place at Temperance Hall in Knoxville on May 30–31. Over four hundred delegates representing twenty-eight counties attended. Thomas A.R. Nelson of Washington County was appointed president. Nelson spoke for an hour, during which time he denounced the state government’s pro-secession actions as unconstitutional. The delegation then drafted a list of grievances and resolutions. U.S. senator Andrew Johnson was also in attendance and spoke for nearly three hours. He further condemned the state government’s disregard for the U.S. Constitution and claimed leadership had fallen prey to “fanaticism.” It was resolved by the delegates that the governor did not have the authority to enter into a military league with the Confederacy. The meeting adjourned, but before leaving, delegates planned to meet again in the very near future.24

On June 8, Unionists suffered a devastating defeat as Tennessee voters approved an ordinance of secession by a vote of 101,486 to 46,520, thereby giving the state government power to sever its ties with the United States and join the Confederacy. East Tennessee voters had opposed the ordinance by a 32,205 to 14,095 margin.25 While Tennessee had officially seceded, many East Tennessee Unionists were determined to be a thorn in the side of the Confederate government.

Nelson called for a second convention of Unionists to be held in Greeneville, Tennessee, on June 17. During the four-day meeting, there were lengthy debates as to what action could be taken by East Tennessee. After much deliberation, a series of resolutions was passed. These resolutions expressed that East Tennessee desired to remain neutral in the coming war; that the legislature’s acts of declaring Tennessee independence and joining a military league were unconstitutional; that East Tennessee would defend itself if occupied by Confederate forces and would retaliate if any delegates were harmed. Delegates also formed a commission to travel to Nashville in order to seek permission from the legislature to form a separate state from the eastern counties. They agreed that even if statehood was rejected by the legislature, East Tennesseans held the right to determine their own destiny. Finally, a “Declaration of Grievances” was adopted proclaiming that East Tennessee would remain within the Union, affirming that the Lincoln administration had given them no reason to secede.26

The memorial requesting that East Tennessee be separated from the state of Tennessee was largely ignored by the state legislature. The Confederacy could not, and would not, allow such an essential area to break away. The region provided a vital transportation and communications link, as well as great resources in the way of food, livestock and minerals. Connecting rail lines of the East Tennessee and Virginia (ET&V) and East Tennessee and Georgia (ET&G) Railroads passed through the great valley from Bristol to Chattanooga. The Confederacy needed these rail lines to transport troops and materials to military theaters in the East and South. Additionally, East Tennessee held great value in wheat production and was also an important source of raw materials like copper, lead and saltpeter. To lose this area not only would create serious logistical problems but would also open an avenue of invasion by the Union army into the heartland of the Confederacy.27

East Tennessee Unionists nevertheless were bitter about the legislative snub of separation. As a result, some began to leave the area, as they were unwilling to live under Confederate occupation. Others traveled to Kentucky in order to join the Union army. Yet many other Unionists remained unyielding and were determined to fight for their homes. Some began laying plans of sabotage aimed at Confederate war efforts, while still others planned to raise their own military forces to engage in guerrilla warfare. Joseph Wagner, who had helped Samuel Northington disarm secessionists in Johnson County, began recruiting forces. He was elected colonel of the county militia and enrolled nearly 250 men. Eventually, Wagner would be commissioned a major with the Thirteenth Tennessee Volunteer Cavalry and his men added to the muster rolls.28

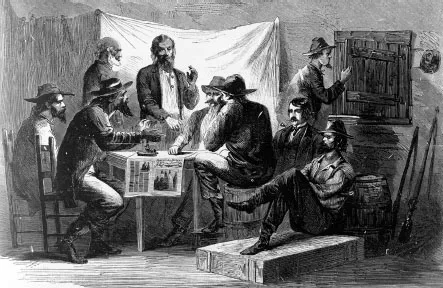

Secret Meeting of Southern Unionists as sketched by Civil War artist Alfred R. Waud and appeared in Harper’s Weekly on August 4, 1866. After Tennessee seceded and joined the Confederate States of America, many Unionists met in secret to plot sabotage against the Confederacy or to discuss plans for crossing the mountains into Kentucky to join the Union army. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

To defend the region against any invasion Union forces might launch, Confederate leadership assigned General Felix K. Zollicoffer to command the Confederate District of East Tennessee. A native of Middle Tennessee, Zollicoffer had no formal military training except for a brief stint in the army during the Seminole War in Florida during the 1830s. Before the war, Zollicoffer had worked primarily as a newspaper editor. Historians have often criticized him for being an incompetent political general, but to be fair, he was placed in an untenable position. Faced with communication and supply problems that the mountainous region of East Tennessee presented, Zollicoffer had to maintain the longest line of defense for the Confederacy with a small number of poorly armed men. Not to mention his command encompassed an area that contained the least amount of support for the Confederacy and the greatest amount of Unionist activity.29

Interestingly, Zollicoffer did not support the early secessionist movement in Tennessee. He did not believe the election of Abraham Lincoln constituted such a threat that necessitated dissolving the Union. Yet when fighting erupted at Fort Sumter and Lincoln called for troops to use against the South, Zollicoffer, along with many other Tennesseans, abandoned support for the Union cause. He now believed that all Tennesseans, without regard to any former attachment to the Federal Union, should support the Confederacy. His orders from Adjutant and Inspector General Samuel Cooper were to “preserve peace, protect the railroad, and repel invasion.”30 After establishing his headquarters at Knoxville, Zollicoffer dispatched troops to prepare the defenses against a Northern invasion. He reasoned that the best way to deal with Unionists was through leniency. To that end, he issued a proclamation addressed “To the People of East Tennessee” in August 1861. He firmly declared that treason against the state “will not be tolerated” but then reassured citizens that “no man’s rights, property, or privileges shall be disturbed.” Zollicoffer explained the military was there only to protect the people from invasion and to prevent “the horrors of civil war.” Further, he appealed to the “Union men” not to be swept up in any excitement so as to bring destruction to their fellow Tennesseans.31

Yet the Confederate government remained alarmed, with good reason, about the possibility of sabotaging the vital communication and railroad bridges on the ET&V and ET&G lines. Individuals such as Roderick Butler and Samuel Northington were singled out by Zollicoffer as potential troublemakers, and he ordered that these men, along with other so-called Lincolnites in East Tennessee, be placed under close observation. Zollicoffer continued that he wanted “as much as possible to be conciliatory”; however, if “satisfactory evidence” was obtained that these men or others like them were promoting “open hostility to the authorities of the State and of the Confederate States,” they should be arrested and detained.32 In a letter to Confederate secretary of war Leroy P. Walker, Governor Harris openly expressed his concerns, saying, “There will be an effort on the part of the Federal Government to arm the Union men of Tennessee I have no doubt.” Because of the threat the Union element posed for Harris, he indicated that his government would “have to adopt a decid...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. “A Civil War Among Us”

- 2. “Rally ’Round the Flag”

- 3. “You Have Killed the Best Man in the Southern Confederacy”

- 4. “A Night of Horror”

- 5. Stoneman’s “Cossacks”

- 6. “Such Are the Fortunes of War”

- 7. “Their Glory Shall Not Be Blotted Out”

- Notes

- About the Author