- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Wicked Columbus, Ohio

About this book

Ohio's capital city once teemed with crime bosses, rampant corruption and unpunished perversion. The Bad Lands of Columbus was a nationally recognized slum controlled by "Smoky" Hobbs. Columbus native Dr. Samuel B. Hartman, the world's most successful snake oil salesman, was almost single-handedly responsible for the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act. Local gambler "Pat" Murnan had an unlikely love affair with Grace Backenstoe, the madam of the most popular brothel in town. The two were a symbol of the area's salaciousness. Authors David Meyers and Elise Meyers Walker explore the heyday of Columbus's most notorious fiends, corrupt politicians and con men.

Information

Chapter 1

ADVENTURES IN THE SKIN GAME

The most horrible and revolting chapter in the history of Ohio, was contributed by the Democratic officers at the Penitentiary, at Columbus, under the administration of Governor Hoadly, the last Democratic administration which the state wants.

–anonymous pamphleteer

As politicians go, Joseph Benson Foraker was an honorable man. Had he ascended to the office of president of the United States (once considered a distinct possibility), his may well have been one of the faces gracing Mount Rushmore. However, in 1886 he wanted nothing more than to serve a second two-year term as governor of Ohio. In a speech to the Republican faithful at the Metropolitan Opera House in Columbus on September 24, 1886, he charged that several officers of the Ohio Penitentiary—Democrats all—had been in the practice of skinning the bodies of dead prisoners and using their hides to manufacture walking sticks. This was just one in a litany of crimes that he said had occurred under the not-so-watchful eye of his predecessor, Democrat George Hoadly.

Hoadly was something of a bumbler. In 1884, at the onset of his single term as governor, rioting broke out in Cincinnati after a jury returned a verdict of manslaughter when a sizable number of its citizenry believed it should have been murder. (Even the trial judge called the verdict “a damned outrage.”) Suspecting that the outcome had been rigged, an unruly mob went on a rampage for three days. At least forty-five people died before Hoadly reluctantly sent in troops to restore order.

When Foraker took office in January 1886, he replaced Hoadly’s man, Isaac G. Peetry, with his own, Elijah G. Coffin, as warden of the penitentiary. In keeping with the political spoils system practiced by both parties, Coffin effected a wholesale change in penitentiary staff—managers, officers and guards—with the exception of L.L. Lang, chief clerk. He then asserted in his annual report, “That the Ohio Penitentiary has fallen upon hard lines, and that its operations have been greatly misguided within recent years, no one familiar with its history can question.”

In support of this allegation, Foraker had an affidavit from Frederick W. Nye, an inmate, who swore that he had been ordered to assist Dr. C.R. Montgomery, chief physician, and Dr. W.W. Homes, superintendent of the prison hospital, in stripping the skin from the sides and backs of seven or eight deceased inmates. Nye described the events in horrific detail:

After so taking the skins, I would bring them in a basket to my private work room (known as “the shed”), where I would cut the skins into strips in order that they might become seasoned quicker than if I left them in the entire pieces. I would then put these strips of skin into a basket that I would hang up high on the inside of a narrow, open window in the shed in order that the air circulating through would quickly season and fit them for use in the manufacture of canes. When the skins became seasoned of a degree to allow of their being worked up, I would cut them into small, square pieces and perforate each piece in the center for a steel rod to pass through, after which by planning and paring, neat walking sticks could be produced, averaging in size from ¼ of an inch at the bottom to ⅝ of an inch at the top.

According to Nye, the work was so sickening that the doctors supplied him with six-ounce phials of whiskey so he could continue. Nevertheless, he was compelled to spend many days in bed “on account of the offensive nature of the work.” He completed five canes in all, two each for the doctors and one that he kept for himself and turned over to Governor Foraker with his notarized statement. Another inmate, Hunt, is said to have coated the canes with varnish to contain the smell. Nye even identified the prisoners whose skin was used to make them: Joseph McCoy and John W. Slater.

The Democratic press and party immediately denounced Nye’s claim. They were particularly skeptical that the skinned inmates were an Irishman (nearly all Democrats to a man) and an African American (a group they’d been actively wooing). How could the word of a convict be taken over the reputations of Drs. Montgomery and Homes? Governor Foraker didn’t—not at first, anyway. He sought verification from Dr. D.N. Kinsman, possibly the most respected physician in the city, who examined several disks removed from the cane under a microscope. Kinsman concluded that there were three different kinds used:

White disks, which are made from the skin of a white person.

Dark disks, which are evidently made from the skin of a colored person.

Black disks, made from the tanned skin of some animal.

Dark disks, which are evidently made from the skin of a colored person.

Black disks, made from the tanned skin of some animal.

In his statement, Nye described how he alternated every six pieces of human skin with one of calfskin.

Edward Savanac, night nurse and cook at the penitentiary hospital, attested that he

saw Nye working the skins into canes, and the sight was a most revolting one, because of the fact that the skins were yet green, and when they were hammered over the steel on which the small pieces of skin, with occasional pieces of leather, were strung, the substance would spurt out over the floor and other things about it, producing a great stench, that would often compel the said Nye to quit his work, sometimes for days at a time.

Another affidavit was obtained from sixty-nine-year-old Joel F. Skillen, who had rented Dr. Montgomery an office in the basement of his house at 84 East Town Street. Skillen, an auctioneer and rooming house operator, said that on one occasion he had accompanied Montgomery to the prison dead-house to view the autopsy of a recently deceased inmate. In the presence of Nye and others, he watched the doctor strip pieces of skin from the corpse of a black man and place them in a basket. “[H]e cut the skin from one side to the other, and then, with the assistance of some convicts, tore the skin from the stomach and chest back to the shoulders and hips,” Skillen said. “He then turned the body over and cut it down the back and finished taking the skin from the body.” He said he became so sickened by the sight that he immediately left the penitentiary.

A former night guard at the prison hospital, Alexander Gonder, purportedly informed D.A. Austin about the “horrible stench” coming from “Nye’s cane factory” and the pains he had taken to rid the building of it. However, at the time he had no knowledge of its source. Inmate Charles Jackson also confirmed that there were odors emanating from the room. He further claimed that many convicts knew about the cane-making operation.

However, cane-making may not have been the only use for human hide at the penitentiary. John Faulhaber, foreman at Schauweker Brothers Oak Leather Company on West Main Street, stated that Dr. Montgomery had approached him about tanning the skin of a prisoner who was soon to be hanged. The doctor emphasized that he was quite eager to have a “perfect skin”—one from head to toe. Despite Montgomery’s insistence that he would pay him generously, Faulhaber told him that they did not do that kind of work.

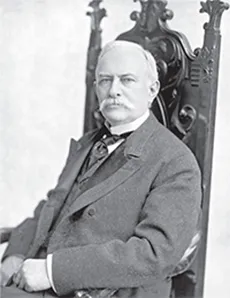

If he hadn’t run afoul of Theodore Roosevelt, Senator Joseph B. Foraker might have become president of the United States. Library of Congress.

L.L. Lang, a Democrat who had worked at the penitentiary during Hoadly’s administration, said that the skinning was common knowledge at the prison, while Andrew Redman reported that he had a piece of skin given to him by an ex-guard. A barber on High Street had a razor strap, possibly from the hide of a horse thief, that he had obtained from another barber, Edward Elderkin, who said that it was a gift from a young physician, Dr. Fred Gunsaulus, from the Ohio Penitentiary. Although Gunsaulus hadn’t graduated from medical school at the time, he was hired as a prison guard and given the duties of assistant physician. And a former prison guard from Loudonville, Gustave Schweenker, was alleged to have shown his neighbors a piece of leather that he said was from a black inmate.

In the days following Foraker’s speech, other stories began to circulate. A bartender on High Street was said to have a piece of skin from Patrick Harnett, a murderer from Cincinnati whose head had been ripped from his body when he was hanged in September 1885. The bartender used this “souvenir” to frighten the timid by inviting them to examine it before telling them what it was. A Dayton Democrat was rumored to have a cane, and another in Sidney had a piece of hide. And Colonel W.E. Bundy of Cincinnati was also said to sport one of the canes. There were also rumored to be charms carved from the bones of inmates in circulation among former penitentiary employees.

W.W. Monroe, a Nelsonville dentist, wrote to Foraker, stating that he had discussed the matter with Dr. R.W. Hanson, who had been an assistant in the prison hospital during Democratic rule. Hanson had told him that Dr. Montgomery had nothing to do with the skinning of McCoy. Rather, he had personally cut a piece of skin twelve inches square from the back of the dead inmate and given it to Nye at his request so he could make a cane. However, McCoy was so fat that the skin had “dried like an old piece of bacon rind” and proved unusable.

Dr. Montgomery, who had been replaced at the penitentiary by Dr. John W. Clemmer, a homeopathic physician, denied the allegations. He telegraphed from St. Louis (home of his fiancée) that “Nye was a liar and the bodies referred to by him were buried in the Penitentiary grounds.”

By October 1886, Dr. Homes was proprietor of a drugstore at the corner of Eighth and Naghten Streets. He said that the body of McCoy “was delivered to the Columbus Medical College, in pursuance of the statute in such case, on the 22d day of October, 1885, unmutilated and in good condition, and that the body of…Slater, in pursuance or the same statute and in like condition, was on the 24th day of November, 1885, delivered to Starling Medical College, of Columbus, Ohio.”

Nelson Obetz, MD, demonstrator of anatomy at the Starling Medical College, made a sworn statement that he received the dead body of Slater from Warden Peetry and that the body was in good condition, “without a particle of skin removed.” He added that all bodies received from the penitentiary were in good condition and were never “skinned” or otherwise mutilated. Likewise, Wesley Gallogly, MD, a Republican then living in Missouri, stated than he received the unmutilated body of Joseph McCoy while working at the Columbus Medical College. During the ensuing investigation of the canes and other possible crimes committed in the prison, allegations surfaced that someone had attempted to poison several of the inmates wanted as witnesses.

It would be easy to dismiss the claims of inmate Nye, a horse thief who was hoping to receive a pardon from the governor, except for two things: Dr. Kinsman’s assertion that the cane he examined was constructed of human skin and the fact that at least one of these canes still exists and came up for auction within the past few years. There is also precedent for keeping such grisly souvenirs of executed criminals. For example, it was not at all unusual for the executioner or the sheriff to sell pieces of the rope used to hang a condemned person (William Corder, Suffolk, England, 1828). There were also instances of using a dead man’s skin to make wallets (Antoine LeBlanc, Morristown, New Jersey, 1833) or to bind books (William Burke, Edinburgh, Scotland, 1831). In 1883, Governor Benjamin Butler of Massachusetts discovered a veritable industry in dead people at the Tewksbury Almshouse that ranged from selling infant cadavers to Harvard Medical to making slippers out of tanned human skin. And in Columbus, Dr. Ichabod Gibson Jones kept the foot of William Graham in a bottle on his desk after he was hanged along with Esther Foster in 1844.1

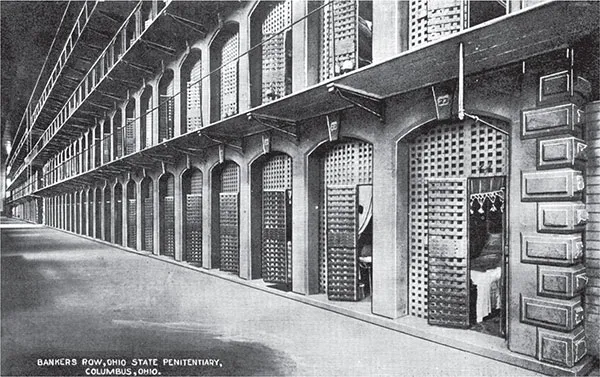

“Banker’s Row” at the Ohio Penitentiary provided nicer accommodations for well-connected inmates. Authors’ collection.

The Ohio legislature enacted a law in 1881 that permitted medical schools to legally acquire unclaimed bodies from public institutions. However, the competition for these scarce resources remained fierce. The medical colleges of Columbus searched far and wide for anatomical specimens. In January 1887, it was discovered that the bodies of paupers were being shipped from the country infirmary to Columbus medical colleges in boxes labelled “glass.” A month later, the Columbus Medical College initiated a suit in London, Ohio, to obtain possession of the body of an unidentified man who had been killed in a railroad accident a few weeks earlier. Obviously, the condition of the corpse did not discourage them.

Prior to the passage of the anatomy law, grave robbing had been regarded by many of the medical schools as a necessary evil. For example, in July 1878, a Columbus police officer named McGrath “heard a noise in the rear of the Columbus Medical College building.” Vaulting over a fence, he surprised two men who were attempting to enter the school through a basement door. He promptly nabbed them and then summoned assistance by blowing his whistle. When other officers arrived, they discovered that a third man was inside awaiting the delivery of a body “which was found in a sack just in front of the door, with the hook already in the sack ready to hoist the body to the dissecting room in the upper story of the building.” The three men who were apprehended—all medical students—were bailed out of jail by “some of the city physicians.”

Apparently, grave robbing did not abate following the passage of the law. In January 1892, a “corpse stolen from Mt. Vernon [Ohio] was found in a Columbus medical college partially dissected.” The same month, two students of “Sterling Medical college” were arrested at their homes in Mount Sterling, Ohio, for robbing a grave in Shiloh, Ohio, near Five Points. The community was so incensed by theft of the body of Emma Baggs that there were threats of lynching.

Grave robbing aside, how honorable were the doctors otherwise? In 1882, the state medical board of West Virginia challenged the credentials of one graduate of the Columbus Medical College, Dr. A.M. Dent, when it was discovered that he had graduated from the institution after attending for no more than three or four weeks. A member of the faculty and editor of the Columbus Medical Journal, Dr. James F. Baldwin, had asserted that the man “didn’t know what the iris was, not the pupil, could not locate the mitral or tricuspid valves; placed the valvulae conniventes in the brain, and the ileocecal valve in the rectum!” Baldwin was promptly fired from the school for his outspokenness, while Dr. J.W. Hamilton, owner of the college, naturally denied the accusations. And Dr. D.N. Kinsman, dean of the school, declared that the student in question had passed with “a high grade, particularly in obstetrics.” This was the same Dr. Kinsman who had attested to the fact that the cane was made from human skin.

Since cadavers would continue to be hard to come by, it is not difficult to imagine that the physicians at the various medical colleges would be reluctant to complain if the specimens they received from the Ohio Penitentiary were in less than pristine condition. At least they were reasonably fresh. They also weren’t particularly concerned about the disposition of the dissected bodies. This callous disregard is illustrated by an incident in June 1889, when the partial remains of three such persons were found in a dump outside Columbus, apparently deposited there from one of the local medical colleges.

Not surprising, then, that the outrage regarding the alleged skinning of a few inmate cadavers quickly died down once it had serve its political purpose. Perhaps the only lasting impact was the nickname that Governor (and, later, Senator) Foraker’s detractors gave him: “Skin Cane.”

Chapter 2

MURDER IN COWTOWN

England had its “Jack the Ripper,” but it was left to America, and to Columbus, Ohio, to furnish a more inhuman fiend than was ever yet arrested, tried, condemned, or imprisoned.

–Daniel J. Morgan, historian

Many a “ripperologist”—Colin Wilson’s term for an expert on Jack the Ripper—has noted that similar spates of murders have occurred at various times throughout the United States, and Ohio is no exception. Cincinnati had its own ripper, Dayton its strangler and Cleveland its torso killer. But in Columbus, there was one difference: the victims were not women but cows. To Morgan’s way of thinking, that somehow made the crimes even more heinous.2

In the early 1890s, Columbus was terrorized by a number of brutal cow slayings, some eight or ten, possibly even a dozen or more (newspaper accounts are jumbled)—and perhaps a horse as well. Their carcasses were found cut to pieces while still alive and mutilated in an unspeakable manner, although people did speak of it—a lot. In vain did the police search for this “Cow Fiend” over the course of several months, while the public’s imagination ran wild, fired by images of the Grendel-like monster that walked among them.

The reign of terror began on July 2, 1892, with the butchering of a cow owned by John Gorman, a dairyman living in Milo Village near the Panhandle Railroad shops.3 The random killing of livestock was not unheard of during that era, and at first, no one was particularly alarmed. However, this incident was soon followed by the killing and mutilation of a cow owne...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction, by Elise Meyers Walker

- 1. Adventures in the Skin Game

- 2. Murder in Cowtown

- 3. She’ll Be Loaded with Peruna When She Comes

- 4. A Boyish Prank

- 5. Wild in the Streets

- 6. The Invisible Detective

- 7. Vanishing Act

- 8. A Woman Scorned

- 9. King of the Bad Lands

- 10. Taking a Chance on Love

- 11. Slouching Toward Graceland

- 12. The Pornographer’s Wife

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- About the Authors

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Wicked Columbus, Ohio by David Myers,Elise Meyers Walker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.