- 131 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

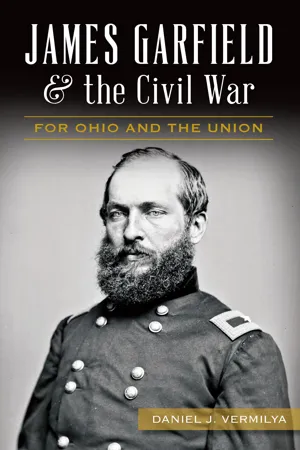

This biography of America's twentieth president sheds light on his Civil War years, when he served as a major general for the Union Army.

While his presidency was tragically cut short by his assassination, James Abraham Garfield's eventful life covered some of the most consequential years of American history. When the United States was divided by war, Garfield was one of many who stepped forward to defend the Union. In this biography, historian Daniel J. Vermilya reveals the little-known story of Garfield's role in the Civil War.

From humble beginnings in Ohio, Garfield rose to become a major general in the Union army. His military career took him to the backwoods of Kentucky, the fields of Shiloh and Chickamauga, and ultimately to the halls of Congress. His service during the war established Garfield as a courageous leader who would one day lead the country as president.

While his presidency was tragically cut short by his assassination, James Abraham Garfield's eventful life covered some of the most consequential years of American history. When the United States was divided by war, Garfield was one of many who stepped forward to defend the Union. In this biography, historian Daniel J. Vermilya reveals the little-known story of Garfield's role in the Civil War.

From humble beginnings in Ohio, Garfield rose to become a major general in the Union army. His military career took him to the backwoods of Kentucky, the fields of Shiloh and Chickamauga, and ultimately to the halls of Congress. His service during the war established Garfield as a courageous leader who would one day lead the country as president.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access James Garfield & the Civil War by Daniel J Vermilya in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Son of the Western Reserve

NOVEMBER 1831–JANUARY 1860

The world talks about self-made men. Every man that is made at all is self made.

—James A. Garfield

—James A. Garfield

Like so many whose names would enter into the history books during the American Civil War, James Garfield came from inauspicious and humble beginnings. His parents—Abram and Eliza Garfield—moved from New England to the backwoods region of northeast Ohio in 1820, shortly after their marriage. Twenty-two and nineteen, respectively, Abram and Eliza were leaving family behind and starting a new adventure. In the early days of western expansion, this part of Ohio had been claimed by Connecticut as the Western Reserve. Just south of Lake Erie, the land of the Western Reserve ran from the western border of Pennsylvania to a line 120 miles to the west, going as far south as present-day Youngstown, Ohio. Connecticut continued to hold over three million acres of land in the Western Reserve until 1800, when the land was formally handed over to the federal government, becoming part of the Northwest Territory. This territory was auspicious for several reasons, most notably because the U.S. Congress, in one of its first and most important official actions, officially banned slavery from the region with the Northwest Ordinance. In 1803—just seventeen years before Abram and Eliza arrived there—Ohio had enough settlers to become the seventeenth state in the Union. The Garfield family settled near the Cuyahoga River, and their first years in Ohio were spent fighting off sickness and raising several children. By 1830, the family had purchased twenty acres of land in Orange Township, a small village with just over three hundred residents, located on the cusp of the Chagrin River Valley.1

It was here where, on November 19, 1831, James Abram Garfield was born. Named for an earlier child who had died when only two, young James entered life with both health and size. “James A. was the largest Babe I ever had,” Eliza would later note. “He looked like a red Irishman.” James was the fifth child for Abram and Eliza. While his namesake, James Ballou, died in 1829, Mehitabel, Thomas and Mary had all survived infancy and the perils of frontier life. Much like his siblings, James Abram was born in a log cabin and into a world and lifestyle that was far from privileged and easy. In 1831, the largest city in the former Western Reserve was Cleveland, with a population of just over one thousand people. The Garfield family did not have the benefits of wealth or prestige; rather, they relied on a strong, industrious patriarch who labored to ensure his family’s safety and success. “Your father would do as much work in one day as any man would in two,” Eliza wrote to James years later.2

Unfortunately, due to a cruel twist of fate, Abram’s hard work and support would not last for long. In 1833, he fell gravely ill after an arduous day working outdoors. According to most accounts, he had been fighting a forest fire that threatened his family’s land, and afterward he had a “violent cold,” which was most likely a form of pneumonia. Despite the efforts of a local doctor, within a few days, Abram Garfield was dead. His death left thirtyone-year-old Eliza behind with four young children. The young widow was to carry out the jobs of mother, farmer, seamstress, educator, cobbler and whatever else was necessary around the homestead.3

Growing up under these circumstances made things difficult for the Garfield children, but James managed to avoid the worst of the burden due to his young age. His mother described him as “a very good natured child” but one who was “[a]lways uneasy, very quick to learn, he was rather lazy, did not like to work the best that ever was.” Instead of work, James much preferred the outdoors and hunting as he gained in size and strength.4

Even more than the outdoors, James had a passion for books and reading, something that would come to have a dominating and determining influence on his life. While he received some education in a small one-room schoolhouse, it was his readings at home that truly captured his attention. The King James Bible and history books about the American Revolution were captivating reads for the young Garfield, but fiction held a particular sway with him. It was reading that helped to expand Garfield’s mind, opening up new hopes, possibilities and expectations. When he was sixteen, it was no longer enough for him simply to read of other places. Finding his life at home boring and tedious, in 1848, Garfield said goodbye to his mother and headed for the city to make his own way.5

James first went to Cleveland, where he intended to begin a life as a sailor on the Great Lakes. After being rudely and profanely rejected by the captain of a ship, James turned his hopes from traveling the Great Lakes to working on a canalboat. That August, James came aboard the Evening Star, journeying in between Cleveland and Pittsburgh. Despite being a strong and healthy sixteen-year-old, Garfield’s six-week tenure provided a stern and cold lesson of reality: he fell into the water over a dozen times, fought with other crew members and by October had come down with a terrible illness. James returned home to his mother, who took him in and helped him back to health. After a brief stint away from home, James had experienced his share of rough-and-tumble living for the time being. Having failed his first test in the real world, James would soon begin a different path.

“SLEEPING THUNDER”

In early 1849, putting his canal experiences behind him, seventeen-year-old James Garfield journeyed to Chester, Ohio, on the other side of the Chagrin River Valley, where he enrolled in the Geauga Seminary, one of several local schools that offered an advanced level of study for those who sought more than a one-room schoolhouse. Founded by Free Will Baptists, the school taught basics such as Latin, algebra and grammar. Because of his family’s poor financial state, Garfield worked as a carpenter to pay for his tuition, room and board. He ate a spartan diet, and his few clothing items were exceedingly threadbare and worn. By the time he turned eighteen, Garfield had begun teaching at a district school in Solon to help support himself.

Such obstacles would have overcome many, but this was nothing new for Garfield. He had grown up with nothing but the essentials, and his father and mother had provided him with two examples of how to work faithfully and industriously. James took these lessons to heart, and because of it, these times were crucial to forming him into the man who just fifteen years later would be a major general in the Union army. It was also here at the Geauga Seminary where Garfield first met Lucretia Rudolph, a fellow student who would play a large role in his future.6

Major events soon began to transpire in Garfield’s life, furthering him along his path toward notoriety and prominence. In March 1850, he attended a camp meeting for the Disciples of Christ, a new branch of Christianity that arose during the Second Great Awakening of the mid-1800s. Sometimes referred to as Campbellites, after the preacher Alexander Campbell, the adherents of this faith believed strongly in forgoing worldly affairs such as politics. Instead, they focused on living out God’s commandments as outlined in the Bible. Garfield’s parents had been Disciples of Christ, but until now, he had not given great thought to this message. After attending the camp meeting, however, Garfield was a changed man. The message moved him, and on March 4, 1850—thirty-one years to the day before he was inaugurated as the twentieth president of the United States—he was baptized in the waters of the Chagrin River, rising anew as an affirmed Christian and Disciple of Christ.7

For the first time in his life, Garfield believed he was destined for greater things. He began to work more industriously than ever to make something of himself. In his diary, which he started in 1848, he reflected on his recent changes, writing, “Thus by the Providence of God I am what I am and not a sailor. I thank Him.” Soon, his diary was filled with ponderings about his life and his purpose. “I know without egotism,” he noted, “that there is some of the sleeping thunder in my soul and it shall come out!”8

In this spirit, Garfield soon sought out a change of scenery. To the south, in Hiram, there was a new school that had been founded by the Disciples of Christ. The Western Reserve Eclectic Institute, later known as Hiram College, offered a different type of education for Garfield. It was more advanced than the Geauga Seminary, and it was in alignment with his strong religious beliefs. In the spring of 1851, he enrolled at the school in Hiram and began an association with the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute that would last—in one form or another—over the next decade and more.

At Hiram, Garfield was immersed in academics. He spent his days with classical Greek and Latin, geometry, philosophy, geology and more, all of which sharpened his abilities as a writer, speaker and debater. His zeal for knowledge and learning was consuming. Years later, Harvey Everest, one of his fellow students, would look back on Garfield’s early days at Hiram and recall, “He did not study merely to recite well but to know and for the pleasure of learning and knowing.” On many an evening, Garfield would study well into the late hours of the night, waiting for the lights in the rooms of other students to be extinguished before he would even consider stopping for the day.9

Working as a janitor at the school to pay his way, studying at all hours of the day and night, debating others on questions of philosophy and religion—these early years at Hiram saw Garfield truly come into his own. He was developing and refining qualities and characteristics that would help him excel in his future endeavors. While he helped to organize the Philomathean Society, a debating group on campus, he still held true to his Disciple disinclination toward politics. In 1852, he expressed disgust over “the wire-pulling of politicians and the total disregard of truth in all their operations.” Garfield much preferred to eschew politics and devote his life instead to God, writing, “It looks to me like serving two masters to participate in the affairs of a government which is point blank opposed to the Christian (as all human ones must necessarily be.)”10

During the winter of 1853, Garfield began teaching at the Eclectic Institute and preaching in local Disciple churches. His schedule was exhausting. Most days saw Garfield begin his work at five o’clock in the morning, and he did not finish until nearly eleven o’clock at night. On Sundays, he could frequently be seen preaching in at least two different churches. In addition to these busy hours, he was developing a romantic relationship with Lucretia Rudolph, his former classmate at Geauga who had also enrolled at the Eclectic Institute.

In 1854, his hectic schedule could no longer hold Garfield in Ohio. He set his sights elsewhere for academics and distinction. His search ultimately led him to Massachusetts, where that summer he enrolled in Williams College. It was a personal response from Mark Hopkins, the president of the school, that sold Garfield on attending a school so far from home. Hopkins came to have a tremendous impact on Garfield, and the two remained in touch for the rest of Garfield’s life.

Upon arriving at the college, Garfield tested into the junior class. With a challenging course load, he studied the natural sciences and new foreign languages, such as German. His skill as a debater helped him to win friends and ingratiate himself into a new social life. He took part in the campus theological society and listened to lectures from men such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, whose words Garfield described as a “thunderstorm of eloquent thoughts” that caused him to feel “small and insignificant.”11

Williams College provided Garfield the room he needed to grow in numerous ways, one in particular being his feelings on slavery in the United States, the preeminent political issue of the nineteenth century. When Garfield had been a student in Ohio, he had never paid much attention to slavery or abolitionists. Now, after being separated from the strong Disciple confines of Hiram, Garfield was entering into a new world. In late 1855, he listened to several speeches on the western expansion of slavery into new territories. In response, Garfield penned a diary entry reflecting his deep concerns over the future of the country and the immorality of slavery. “I have been instructed tonight on the political condition of our country,” he wrote. “At such hours as this I feel like throwing the whole current of my life into the work of opposing this Giant Evil. I don’t know but the religion of Christ demands such action.” Just three years before, Garfield had disdained all politics and cared little for abolitionists. Now, he was making the transition from a Disciple of Christ who rejected politics to a man who would one day draw his sword and lead soldiers south to defend the Union.12

By the summer of 1856, Garfield was through at Williams. Just eight years removed from his time working on the Evening Star, Garfield was a college graduate. In the commencement address delivered that year by President Hopkins, a charge had been given to the graduates to go forward and change the world for the better. “Go to your posts; take unto you the whole armor of God; watch the signals and follow the footsteps of your Leader,” Hopkins declared. Adding perhaps an element of grim foreshadowing for what lay in store for Garfield, Hopkins continued, “You may fall upon the field before the final peal of victory, but be ye faithful unto death, and ye shall receive a crown of life.”13

Now a college graduate, Garfield returned to Hiram, where new challenges awaited him. After resuming his teaching responsibilities at the Eclectic Institute, in 1857, Garfield was made the president of the school. He was well liked by many of the professors and students, and his work ethic and academic background made him an excellent choice to expand the school’s offerings. On top of teaching a full schedule of classes, Garfield was now also leading the school. Under Garfield’s leadership, students from other denominations began attending the school in increasing numbers.

Garfield’s personal life was changing at this time as well. Throughout the 1850s, Garfield and Lucretia Rudolph had gone from classmates in Geauga to friends with a romantic interest in each other. Garfield had pursued others in this time, but by November 1858, he had set his sights on Lucretia. The two were married that month. Many scholars have speculated that Garfield’s marriage was a source of unhappiness for him. The couple had been engaged since 1854, and some wondered whether the wedding day would ever come. When the day did arrive, it did so without much fanfare. In time, the marriage would become a happy one, but James and “Crete,” as he would affectionately call her, would have their share of trials and tribulations along the way.14

Lucretia Garfield, future first lady of the United States. Library of Congress.

“SERVITIUM ESTO DAMNATUM”

When Garfield returned to Hiram, his interest in politics, which had begun at Williams College, continued to grow. So did his interest in matters of slavery and abolitionism. In 1859, Garfield began studying law, intending to work as a lawyer to supplement his career as an educator. He wrote to a friend in 1858, “I never expect to be satisfied in this life; but yet I think there are other fields in which a man can do more.”15

Garfield was becoming increasingly aware of and involved in politics at a time when sectional fires were burning brighter than ever. The same year he became president of the Eclectic Institute, the Supreme Court issued its infamous Dred Scott v. Sanford decision, further pushing the nation into a crisis over slavery. Garfield soon began speaking publicly on behalf of the new Republican Party, delivering stump speeches for local candidates in the 1858 elections. In 1859, with more elections coming up, the death of a local candidate left an opening for the Republican nomination for the state senator from the Twenty-sixth Ohio Senatorial District. Because of Garfield’s prowess as a debater and public speaker, several Republican leaders came to Hiram and approached him about the seat. After expressing his interest, the Republican delegates took his name to the floor in their convention, and on Augus...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. Son of the Western Reserve

- 2. Let War Come

- 3. To Stand by the Country

- 4. Kentucky

- 5. To Hunt Battles and Bloody Graves

- 6. The Politics of War

- 7. With the Army of the Cumberland

- 8. To Chickamauga and Back

- 9. Veteran

- Appendix A. The Garfield-Rosecrans Controversy

- Appendix B. Garfield’s 1868 Memorial Day Oration

- Notes

- About the Author