- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This Civil War history examines the vital role played by the Pennsylvania capital and the many ways the conflict left its mark on the city and its people.

Answering President Lincoln's call for volunteers, men from across Pennsylvania swarmed Harrisburg to fight for the Union. The cityscape was transformed as soldiers camped on the lawn of the capitol, schools and churches were turned into hospitals and the local fairgrounds became the training facility of Camp Curtin. For four years, Harrisburg and its railroad hub served as a continuous facilitation site for thousands of Northern soldiers on their way to the front lines.

Its vital role in the Union war effort twice placed Harrisburg in the sights of the Confederates—most famously during the Gettysburg Campaign when Southern forces neared the city's outskirts. Though civilians kept an anxious eye to the opposite bank of the Susquehanna River, Harrisburg's defenses were never breached. In Harrisburg and the Civil War, Cooper H. Wingert crafts a portrait of a capital at war, from the political climate to the interactions among the citizens and the troops.

Answering President Lincoln's call for volunteers, men from across Pennsylvania swarmed Harrisburg to fight for the Union. The cityscape was transformed as soldiers camped on the lawn of the capitol, schools and churches were turned into hospitals and the local fairgrounds became the training facility of Camp Curtin. For four years, Harrisburg and its railroad hub served as a continuous facilitation site for thousands of Northern soldiers on their way to the front lines.

Its vital role in the Union war effort twice placed Harrisburg in the sights of the Confederates—most famously during the Gettysburg Campaign when Southern forces neared the city's outskirts. Though civilians kept an anxious eye to the opposite bank of the Susquehanna River, Harrisburg's defenses were never breached. In Harrisburg and the Civil War, Cooper H. Wingert crafts a portrait of a capital at war, from the political climate to the interactions among the citizens and the troops.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Harrisburg and the Civil War by Cooper H Wingert in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Harrisburg’s Initial Responses to the Civil War

All sorts of rumors were afloat, and the operators in the telegraph offices were besieged by anxious applicants.1

–Harrisburg Daily Patriot and Union, April 15, 1861

Since its founding in 1785 by John Harris Jr., Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, had seen unprecedented growth. In 1794, President George Washington passed through the region on his way to suppress the Whiskey Rebellion and was impressed by the bustling young town. After a brief stroll through the settlement, Washington opined that Harrisburg “is considerable for its age (of about eight or nine years).”2 The growth continued long after Washington’s eighteenth-century visit. In 1812, the state capital was relocated to Harrisburg. In the late 1830s, railroads made their appearance, and the sharp, ringing whistle of an incoming locomotive soon became a familiar sound to the residents.

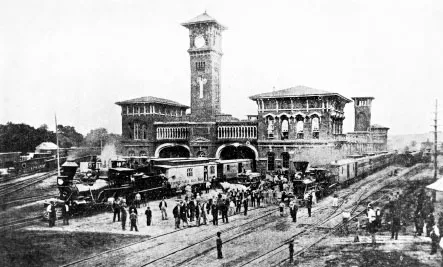

It was not long before the emergent young town became an important railroad hub—various firms were soon competing to extend their lines to Harrisburg.3 The Pennsylvania Railroad Company leased a small station built in 1837 by the Harrisburg and Lancaster Railroad. The thriving industry soon outgrew this small depot, and twenty years later—in 1857—a new and enlarged station was completed and again leased to the Pennsylvania Railroad. With a distinctive Italianate architectural style, the depot measured 400 feet in length by 103 feet in width. The structure additionally boasted “a dining saloon calculated to seat from two hundred and fifty to three hundred persons; ladies’ and gentlemen’s reception rooms; water closets; and a number of offices, including one for the magnetic telegraph owned by the company.” The building cost $58,000 and was first opened to rail traffic on August 1, 1857.4

The first Pennsylvania Railroad depot, completed in 1837 and replaced in 1857. Historical Society of Dauphin County.

The Philadelphia and Reading Railroad also had lines running into Harrisburg. The company had originally been established in 1833 with the goal in mind to complete a railroad extending from Reading to Philadelphia, which was completed six years later after some extended legal barriers. In 1853, the entrepreneurial rail line decided to expand westward, gaining control of the Lebanon Valley Railroad, a line running between Harrisburg and Reading. The Lebanon Valley had been chartered for that purpose—connecting Harrisburg and Reading—but had failed to reach Harrisburg. Although still referred to as the Lebanon Valley, the line was officially redesignated the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, which was completed and first opened in January 1858. The Pennsylvania Railway entered Harrisburg from the south, while the Philadelphia and Reading curled in from the east—crossing the nearby Pennsylvania Canal by an “iron trestle bridge,” with both railroads meeting a short distance above Market Street. There the railway continued northward as the Pennsylvania Railroad.

The Philadelphia and Reading depot was erected opposite the counterpart Pennsylvania Railroad station and between the latter junction of the two lines and the adjacent canal. “It was a homey, easy-going, ramshackle affair,” later recalled one Harrisburger. “The canal bordered the eastern side and the slow-moving canal boats, with the patient, plodding mules helped lend an air of sleepy drowsiness to the calm that enveloped the whole place.” Compared to the Pennsylvania Railroad’s Italianate 1857 station, the Philadelphia and Reading’s depot appeared more like a low-set barn, considering the structure was only nineteen feet high. However, with three tracks running through it and more than forty windows, the building still contained “all the essentials of a first class depot.”5

The second Pennsylvania Railroad depot, photographed in 1863. Historical Society of Dauphin County.

Seemingly always competing with Harrisburg’s extensive railroad network was the Pennsylvania Canal, which ran through the city east of the capitol grounds and what later became the two railways. As New York developed the Erie Canal in the 1820s, the Pennsylvania legislature kept a watchful eye and authorized the construction of the “State Works” in 1826. Eventually, the line would stretch from Columbia northward to Harrisburg and from there would continue twelve miles northwest to the mouth of the Juniata River, where the main line continued west. At Hollidaysburg, the waterway temporarily ended and was linked to Johnstown to its west via the Allegheny Portage Railroad before continuing as a canal to Pittsburgh. The canal began operations in 1834 and would continue until 1901. In 1857, the state sold the majority of the State Works—including the canal running through the eastern part of Harrisburg—to the Pennsylvania Railroad company. By 1860, however, the canal was already in decline, largely due to the rapid growth of the railroad industry; by 1865, the State Works west of Hollidaysburg were no longer in operation.6

Arguably, Harrisburg is today best known for its many and extensive bridges spanning the Susquehanna River. During the mid-nineteenth century, the main way of passage into Harrisburg for foot traffic was the Camelback Bridge, completed in 1817. Named for its distinctive curvature, the privately owned toll bridge attracted much attention. What further separated the covered bridge from its counterparts was its interesting, barn-like design. When Charles Dickens crossed over the bridge, he found travel across the mile-long passage unbearable. Dickens detailed that because the bridge was “roofed and covered in on all sides,” it

was profoundly dark; perplexed, with great beams, crossing and recrossing it at every possible angle; and through the broad chinks and crevices in the floor, the rapid river gleamed, far down below, like a legion of eyes. We had no lamps; and as the horses stumbled and floundered through this place, towards the distant speck of dying light, it seemed interminable. I could not at first persuade myself as we rumbled heavily on, filling the bridge with hollow noises, and I held down my head to save it from the rafters above, but that I was in a painful dream; for I have often dreamed of toiling through such places, and as often argued, even at the time, “this cannot be reality.”7

Unlike Dickens, Harrisburg citizens embraced their unique bridge. When speaking of the Camelback, city residents often cited several “distinguished visitors” who had crossed the river on it. Always being sure to mention Dickens, notwithstanding that the author had termed his journey across the Camelback a “painful dream,” the Camelback was their bridge, and Dickens had mentioned it. The bridge itself had been built in two sections, known as the eastern section, extending from Forster’s (later City) Island to Harrisburg, and the western section, linking Forster’s Island with the western banks of the Susquehanna. The interior of the Camelback was divided into four separate compartments, two situated in the center for various vehicles, horses and livestock and the other two on each side for pedestrian traffic.8

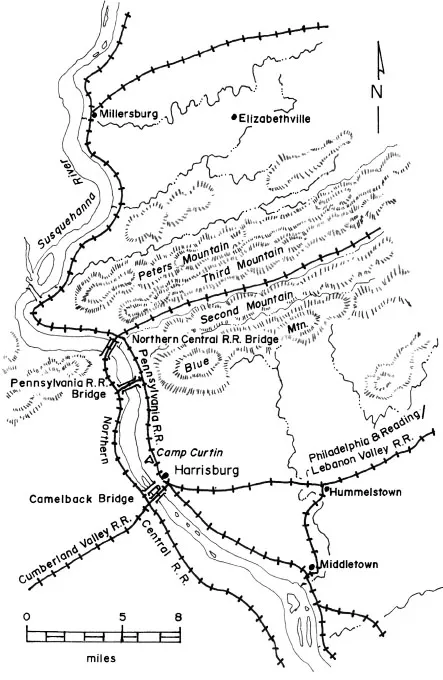

In addition to the Camelback, Harrisburg and the surrounding vicinity was sprawling with railways and railroad bridges. Entering town from the east was the Philadelphia and Reading (Lebanon Valley) Railroad, which met the Pennsylvania Railroad, the latter arriving in Harrisburg from the south. The Pennsylvania Railroad continued north from Harrisburg and crossed to the Susquehanna’s western bank by a bridge just south of Marysville—near where the Rockville bridge stands today. From there, the line extended northwest. The Northern Central Railway made its way down the eastern banks of the Susquehanna from the north but crossed the river on a bridge situated a short distance above the Pennsylvania Railroad bridge and Marysville, just below the small town of Dauphin. The Northern Central continued south along the Susquehanna’s western bank. The Cumberland Valley Railroad, on the other hand, extended from Harrisburg, across the river on a bridge located alongside the Camelback, through Mechanicsburg, Carlisle, Shippensburg and—as its name implies—down the Cumberland Valley to Chambersburg.

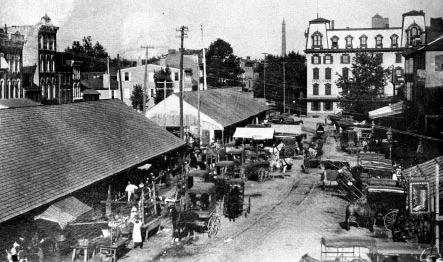

Nestled near the center of the young town was an area referred to as Market Square. Beginning in the 1790s, “market days” were established, and farmers and grocers from Harrisburg and the surrounding vicinity gathered in the square, where they sold and bartered their goods. By 1807, “market sheds”—small, rectangular, pavilion-style structures—had made their appearance, and for the next eighty-odd years, they were among the familiar features of the city. Wednesdays and Saturdays were designated as market days in the square. In the northern section of Harrisburg, the continued expansion of the Fifth and Sixth Wards necessitated a market house be opened there. In 1860, the West Harrisburg Market House—later redesignated the Broad Street Market—debuted at the corner of Third and Verbeke Streets, with market days scheduled for Tuesdays and Fridays so that farmers could still attend the market in the square.9

By 1860, residents of Harrisburg could count more than a dozen hotels situated all about the city. Among the more prominent were the Brady House—which claimed “the advantage of being located nearest the Capitol”—Herr’s Hotel, the European Hotel (also known as Brant’s Hall), the State Capitol Hotel, the Pennsylvania House and the United States Hotel; situated on the square were two of the most visited, the Buehler House and the Jones House. A number of smaller inns also populated the city—Hoffman’s, Mager’s, the Park House, Bomgardner, Susquehanna, Franklin, Seven Stars “and a large number of others not in the heart of the city” all provided plenty of room to accommodate a large number of travelers.10 The Brady House, operated by “Major” Brady, was situated in a five-story brick structure at the corner of Third and State Streets, adjacent to the capitol. “During the Civil War it was the scene of many stirring events and of many important political discussions.” Located on the southern end of the capitol grounds was “Colonel” Omit’s State Capitol Hotel, at the corner of Third and Walnut Streets. “During the sixties and seventies it was one of the most prominent hotels in the city, many of the leading political men of that day making it their headquarters.”11

Railroads near Harrisburg, circa 1860. Map by John Heiser.

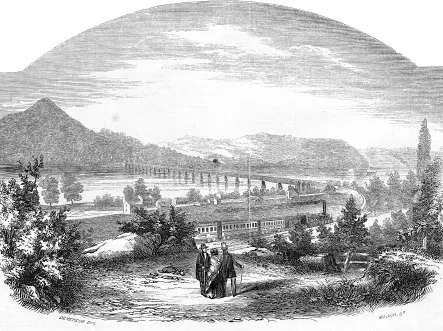

In 1853, a correspondent for the Boston journal Gleason’s Pictorial traveled to the Pennsylvania Railroad bridge north of Harrisburg. The New Englander found the scenery north of the city “delightfully-attractive,” noting that “the entire aspect of the neighborhood is wild and picturesque in its character…The scenery about this spot has all the softness of a splendid agricultural valley, teeming with spirited little villages, and imposing farm-houses, agreeably contrasting with the soft green aspect of bold and lofty mountain ranges, through which the river tamely and serenely winds its peaceful way, like a silver thread.” The paper published the engraving here sketched from the Susquehanna’s eastern banks. The bridge would figure prominently in the transportation of supplies and troops to and from Harrisburg during the war. Author’s collection.

At the “extreme northeastern corner” of Market Square, near Strawberry Street, was the Buehler House, which traced its existence back to the early 1800s. After his disconcerting ride across the Camelback, Charles Dickens spent the night at the hotel, which he later praised in his American Notes. The English author described the establishment as a “snug hotel, which, though smaller and far less splendid than many we put up at, is raised above them all in my remembrance, by having for its landlord the most obliging, considerate, and gentlemanly person I ever had to deal with.” The establishment was initially known as the Eagle Hotel because its sign showed “a beautiful spread eagle.” In 1860, George J. Bolton took over as proprietor. That December, Bolton opened a restaurant “under” the Buehler house. “The rooms have been papered, painted, and fitted up with gas fixtures, so as to give everything a cheerful look, and we are told that the cuisine will be under the immediate supervision of an eminent professor of the art of cooking,” reported the Patriot. “The intention of the proprietor is to serve up all kinds of game in season, to be had in the Eastern or Western markets, and particular attention is to be paid to the oyster and ale departments.” Apparently, William Buehler—the structure’s namesake—retained some form of ownership over the establishment, and Bolton assumed the role of landlord. The Patriot later commented, “Mr. [William] Buehler, the owner of the premises, has displayed a spirit of commendable liberality in refitting and refurnishing this favorite first class establishment from cellar to garret, and we feel certain that Mr. Bolton will make a popular landlord.” During the Civil War, the structure was still known as the Buehler House.12 In September 1866, President Andrew Johnson visited the hotel, accompanied by General Ulysses S. Grant and Admiral David G. Farragut.13

In the late eighteenth century, a “small frame building” was erected on the southeastern corner of what came to be known as Market Square. The structure was dubbed the “Washington Inn” or the “Washington House”—the insignificant inn’s claim to fame being the 1794 visit of President George Washington while he was en route to quell the Whiskey Rebellion. In 1853, the hotel was razed, rebuilt and christened the Jones House after its architect. Prominent guests soon became a recurrent theme at the hotel. In October 1860, the Jones House played host to Albert Edward, Prince of Wales. After somehow managing to escape a thronging crowd surrounding his quarters at the Jones House, the prince and his entourage drove in open carriages to the capitol and ascended the dome to a wondrous view. “There you see the silent Susquehanna, coiled like a serpent in a garden, and spotted with flowery islets,” noted one of the royal following. “You have that pleasant antithesis afforded by an intermingling of hill and valley, mirror-like glimpses of water, verdure, forest, and a town with eleven thousand inhabitants, and after the survey of the prospect you return to terra firma, feeling well repaid for the trouble incurred in ascending the steps.” By 1860, the Jones House was under the proprietorship of “Colonel” Wells Coverly, who was reportedly “making arrangements to increase his accommodations” during the winter of 1860.14

This postwar photograph (circa 1876–89) depicts a typical market day at Harrisburg’s Market Square. Visible in the foreground are the market sheds, and near the center of the photograph are the horse car tracks of the Harrisburg City Passenger Railway, which debuted in 1865. In the right background, note the Buehler House, known as the Bolton House at the time of this image. Historical Society of Dauphin County.

Perhaps the Jones House’s most famous guest arrived shortly before the war broke out in April 1861. En route to his inauguration in Washington in February 1861, President-elect Abraham Lincoln and family were quartered at the hotel. Arriving in Harrisburg around noon on February 22, Lincoln had been informed while in Philadelphia the previous evening that if he were to continue to Washington as planned—meaning a trip through the pro-Southern city of Baltimore—it would only be with “grave peril to his life.” After dining at the Jones House that evening, Lincoln was secreted out of the city and arrived safely in Washington.15

The picturesque capitol grounds were another of Har...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1. Harrisburg’s Initial Responses to the Civil War

- Chapter 2. Camp Curtin and Its Subsidiaries

- Chapter 3. Life in Camp Curtin

- Chapter 4. Civilian-Soldier Interaction in Harrisburg

- Chapter 5. Copperhead Capital: The Politics of Civil War Harrisburg

- Chapter 6. Harrisburg and the Gettysburg Campaign

- Chapter 7. Harrisburg After the Civil War

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Author