![]()

How can warfare be waged with software? The practice of military combat evokes imagery of opposing forces colliding with each other in increasingly sophisticated ways. The spear, the horse and the shield gave way to the bow, the rifle and the missile. Throughout the ages, war charted an evolutionary course in which the finest technology of the time was wielded for organised acts of violence. Efforts to maintain an advantage in warfare had a tremendous effect on other walks of life. The same forge used to craft the blade was also used for the work tool. The innovations in rocketry devised to fuel Cold War ballistic missiles were used to send people into space. A tight-knit symbiosis formed between military technology and its civilian counterparts; one bred the other, the former fed the latter, and vice versa. The development of combat waged over networks—what is colloquially called cyber-warfare—is just one modern iteration of that same cycle of innovation.

The threat landscape is replete with network intrusions, ranging from theft of information to tangible asset loss reaching millions of dollars, and even physical damage. Where many of the tools of warfare are distinctly operated by militaries, many of the most influential network intrusions have notably been perpetrated by civilian intelligence agencies. Increasingly, we see such operations used to pursue offensive objectives, including incapacitating networks, corrupting data, and incurring damage. Should they be assessed on the spectrum of intelligence operations, or warfare?

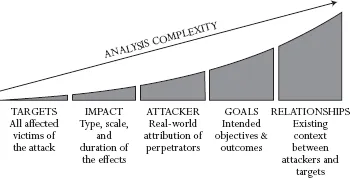

We can improve how we identify when operations qualify as warfare, or even attacks. This chapter will seek to address these questions by offering five cumulative parameters with which network attacks can be individually assessed, those being target, impact, attacker, goals and relationships. Together, the parameters form a model that excludes most incidents which are out of scope for analysis of military-aligned offensive cyber operations. Discerning that the affected targets (1) are of significant quality or quantity is the first milestone in identifying a warfare-threshold activity; a think tank does not equal a military target. Impact (2) includes both the initial observable effects of the attack and its wider consequences, as the vast majority of known incidents have little or no physical effects on the afflicted party. Identifying the attacker (3) establishes attribution to a state or substate entity directing the attacks. Goals (4) relates to assessing that the agenda of the perpetrators is military-strategic, crucial in an ecosystem where most intrusions are motivated by criminality or loose ideology. Finally, relationships (5) addresses the larger geopolitical and strategic considerations in which the attack takes place, and is often the key differentiator between warfare and other adversarial situations. All five parameters must be met if an incident is to qualify as within the spectrum of cyber-warfare.

Standardised assessment based on the above five parameters can help discern between combat and intelligence campaigns, or distinguish a criminal enterprise from a cautious precursor to a military attack. In software-based attacks, these distinctions are often less trivial than they may seem. In the wake of mass exfiltration of sensitive information and nation-sponsored attacks against the banking sector, as has occurred in the US,1 the most resonant question is often “what does this intrusion mean?” If the answer is the devolution of the political situation into armed conflict, it is far more consequential than an embarrassingly successful espionage campaign. This book will address several operations that blur the boundaries between warfare and peacetime, often intentionally. It will also exclude the broader scope of influence campaigns through a focus on offensive operations.

The Venn diagram of military OCOs and cyber-warfare is not a circle. Some offensive cyber operations are carried out in conflict by non-military actors, while militaries may pursue OCOs in peacetime. This book focuses most heavily on the intersection of these two concepts, but through this also looks at borderline cases and instances where countries purposefully blur the lines or pursue mixed strategies. These are educational as they teach us about the flexibility and limitations of attacking information systems for political gain.

The second process included in this chapter is disentangling cyber-warfare and cyberwar. This matters beyond being a bothersome semantic quirk—the two terms are not one and the same. While cyber-warfare can be established as a distinct part of warfare, cyberwar is the quintessential bogeyman used to terrify policy makers into funding inscrutable plans. Cyberwar and cyber-warfare are often used interchangeably in literature and coverage alike to denote any friction between two parties over the internet; this lack of distinction has proven harmful to the overall quality of the discussion. Cyberwar is simply not a meaningful construct and may therefore be replaced with other appropriate labels based on the underlying context and motivation. That may be crime, espionage, attacks, or actual warfare-threshold incidents.

Although it is a thoroughly Western concept, a framing of cyber-warfare must extend beyond its perception in the United States and its allies. Awkward and misappropriated analogies have only detracted from generating agreed-upon standards for what is acceptable and what constitutes a red line. The difficulties in crafting a cohesive notion of offensive cyber operations were suggested at least as early as 2001, when US Air Force veteran Gregory Rattray noted in his book, Strategic Warfare in Cyberspace, that “Frameworks for evaluating the capabilities of international actors to conduct conflicts based on attacking information infrastructures remain underdeveloped”.2 He continued to aptly warn that the label of information warfare was being too broadly applied.

This was exemplified in April 2016 when US Deputy Secretary of Defense Robert Work exclaimed, “We are dropping cyberbombs!”3 as he discussed the ongoing military campaign against the Islamic State. One could almost hear the collective groans of cybersecurity experts worldwide as they witnessed a further sliver of nuance wither away from their craft. The particular phrasing drew criticism, while still serving to reflect the military perception of the value of offensive network capabilities. Time has not improved on such rhetoric, as seen in the wake of the 2020 SolarWinds campaign. Within days of revealing that numerous federal agencies and other organisations had been targeted through a supply chain compromise, Democratic Colorado congressman Jason Crow exclaimed his belief that the incident “could be our modern day, cyber equivalent of Pearl Harbor,”4 a staggering analogy for a campaign that cost no lives and incurred no publicly known effect beyond information loss. Identifying where espionage ends and attacks begin matters a great deal in national security. Across the Atlantic, the Russian-language term for cyberwar—kibervoyna—mostly only exists as an acknowledgement of Western thinking rather than a centrepiece of Russian doctrine.5 As a rising number of nations openly or tacitly acknowledge the significance of various offensive network capabilities to their strategy, cyber-warfare must appropriately expand as a concept to encompass its different varieties. Concurrently, expanding the scope of offensive operations risks diluting analysis beyond utility. Striking a balance between inclusiveness and cohesion is crucial.

This chapter will explore several examples of malicious network activities that—despite their elevated public profiles—should not be depicted as warfare. In 2014, Sony Pictures was the victim of a destructive network attack that resulted in data loss, exfiltration of sensitive information, severe disruption in daily operations and many millions of US dollars in damages.6 In what was at the time a relatively rare act of public attribution, then FBI Director James Comey publicly pointed an accusatory finger at the attackers: “we know who hacked Sony. It was the North Koreans who hacked Sony”.7 The offensive was widely indicated to be a continuation of North Korean policy by cyber means, a strike at the heart of the American studio that dared to publish the parody movie The Interview. The movie presented revered North Korean leader Kim Jong Un in a comical manner with the entire film centred on his attempted assassination. Public attribution efforts of the attack pointed to Unit 121 of the North Korean Reconnaissance General Bureau, one of the nation’s more notorious hacking units8 often associated with offensive network activities.9 By 2018, the US government had indicted an operative affiliated with the North Korean government for this attack and others.10 In this sense, the Sony attack straddled the grey area between warfare and non-warfare activities, with its unique set of capabilities applicable to both. While the visible, high-profile attack held the possibility of escalation, it resulted in no apparent kinetic or virtual countermeasures save heated rhetoric. As the offered model will show, the attack against Sony failed to meet several criteria necessary to qualify as a warfare-threshold incident, even if it was an OCO.

The Boundaries of Cyber-Warfare

When the virtual medium itself is mostly intangible, communicating mutually agreeable limitations on the conduct of war becomes even more significant, even if this communication is tacit. The barrier of entry for conducting some forms of offensive action over the internet has decreased; it is arguably easier to generate a noticeable effect against a military network than it is to physically harm a missile battery. In this sense, the global internet has provided both opportunity and capability, reducing the barrier of entry somewhat.11 However, as we will see, even if it is easier to attempt offensive network operations, the truly impactful operations remain challenging blends of intelligence, operations, and technical skill.

As indicated before, five criteria can help distinguish warfare-level attacks from other offensive incidents, such as financially-motivated criminality, illegal ideological incidents, or even peacetime offensive activities. The parameters are targets, impact, attacker, goals and relationships. They are not ordered by importance, as all five parameters must be met, but rather by increasing difficulty of assessment. Put differently, while identifying the exact intended victim of an attack (step 1) is often the easiest endeavour, surmising the significance of the underlying strategic and political relationship between attacker and target (step 5) is the most daunting of tasks in the process. There is a steep increase in the complexity of analysis required to meet each subsequent parameter. Importantly, the model here has no claim on establishing legality of offensive action within the international order. Though we discuss existing legal frameworks, they are provided as a perspective into assessing incidents.

Figure 1: Five-step model for assessing offensive cyber operations

In information security, incident response to network compromise is an incremental process in which forensic evidence is analysed and assessed against available knowledge of offensive activities. The sequence of criteria in the model reflects the spirit of this process. Identifying the victim is the genesis of any investigation. Once the exact target, targets, or parts thereof have been identified, it becomes possible to deduce the incident’s impact on it, by observing deviations from the target’s normal state of affairs. Based on the victim and the evidence of the attack itself, it then becomes plausible to attempt to identify the incident’s instigators by way of a meticulous attribution process. Only if attribution has been reasonably successful can the observer then gauge motivations and the underlying goals. Finally, the pre-existing relationship between the target’s parent country and the aggressor’s country can be coupled with the overarching context in which this relationship exists.

The first examined parameter is assessing the incident’s affected targets. Beginning the process with a victim assessment provides an early opportunity to classify the attack’s immediate scope. Intrusions against military assets, infrastructure and logistics will clearly meet the threshold, as they are immediately indicative of an adversarial relationship in which at least one party is the warfighting apparatus of a nation or a nation-like entity. Almost unerringly, safeguarding the multitude of military networks and systems is an internal military responsibility, which vast resources and efforts are allocated to.12

A direct attack against military assets would result in a response cycle initiated by the affected military. The affected party may in turn—based on the nature of the attack and its assessed perpetrators—choose to respond in force. This is naturally different than any offensive action—destructive as it may be—which targets a private organisation. An intrusion against Coca Cola has a markedly different significance than one against the British military’s Royal Logistic Corps.

Critical national infrastructure forms the second category against which attacks will meet the required operational threshold of warfare.13 China,14 Russia,15 the United Kingdom16 and the United States17 have all separately acknowledged that attacks against networks of critical national infrastructure (CNI), such as energy, banking and communication, shall be considered as potentially indicative of an armed attack against the nation itself. Critical infrastructure has largely been defined similarly by most nations. As defined by the UK Government’s Centre for the Protection of National Infrastructure (CPNI):

Those critical elements of infrastructure (namely assets, facilities, systems, networks or processes and the essential workers that operate and facilitate them), the loss or compromise of which could result in (a) major detrimental impact on the availability, integrity or delivery of essential services—including those services whose integrity, if compromised, could result in significant loss of life or casualties—taking into account significant economic or social impacts; and/or (b) significant impact on national security, national defence, or the functioning of the state.18

Two incidents are worth evaluating as contrasting examples of targets. The 2014 attacks by North Korea against Sony’s networks, destructive as they may have been, would not constitute warfare due to the nature of Sony Pictures Entertainment as the victim entity; it is a wholly private corporation that serves limited critical functions in the various services it offers. It therefore becomes apparent that the high-profile nature of the attack does not grant the US military recourse over the hack. Conversely, the alleged US–Israeli campai...