![]()

1

The Challenge

It was an execution that led to my twenty-three-year friendship with death row inmate Carey Dean Moore and another one that ended it.

On September 2, 1994, Harold Lamont “Wili” Otey was executed at the Nebraska State Penitentiary (NSP) in Lincoln for the 1977 rape and murder of Jane McManus. He was the first person that Nebraska had put to death in the electric chair since the 1959 execution of mass murderer Charles Starkweather. For a few years prior to Otey’s execution, my children and I participated in vigils and protests against the fulfillment of this death sentence in particular and the death penalty in general. When we first started attending these gatherings, Meredith was a baby whom I carried in a baby carrier on my chest; and Ian was a rambunctious six-year-old who played with the children of other abolitionists. Some of us were members of Nebraskans Against the Death Penalty, some belonged to the NAACP, and some religious denominations were particularly well represented, including the Quaker meeting and the Unitarian Universalist, United Methodist, and Catholic churches. Only occasionally were there counter-protesters, though sometimes people yelled at us from their cars.

On the night of September 1, 1994, we were among the two thousand that gathered outside of the NSP, according to a New York Times estimate. Those of us opposing the execution were a solemn bunch: we sang, prayed, and held candles. But because Otey was a Black man and his victim a white woman, those clamoring for his death were even more vicious than the typical pro-execution crowd. People held signs with barbaric messages such as: “Nebraska State Pen First Annual BBQ”; “Buckwheat says Capital Punishment is OTEY”; “Hey Willie [sic], it’s Fryday”; and “Nebraska—the Good Life for Whites,” the last two words being a qualification of our state slogan. Over the course of the evening, that crowd, a de facto lynch mob, moved from one chant to the next: “Barbecue!” and “Fry the nigger!” Some sported swastikas. Some crowd surfed. A hooded person carried a noose. A woman passing out French fries asked people if they wanted fries with their Otey. Students at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln brandished signs proclaiming their allegiance to a fraternity or sorority or a dormitory floor. That night, I looked into the heart of darkness.

I’ve opposed the death penalty for as long as I can remember. In part, my opposition is practical, as the death penalty is exorbitantly expensive and unfairly applied, doesn’t deter crime, and occasionally results in the death of innocent people. But my chief opposition is grounded in my Christian faith. When Jesus came upon a group of Pharisees and teachers of the law who were about to stone a woman caught in the act of adultery, they set a trap for him. They reminded him that this was legal under Mosaic law. “Now what do you say?” they asked him. As usual, Jesus didn’t deny the legality of a law but raised the bar for its implementation: only those without sin could cast the first stone at the woman. I understand this to mean that even though a society can have a death penalty on the books, Christians can’t support it being carried out because no human has ever or will ever meet the qualification that Jesus set forth. And, too, the gospel message is that deep change can happen any time, any place, and to any person. By executing someone, we cut short that likelihood.

But what I saw on the night of Otey’s execution is that the death penalty is about far more than exacting “life for life, eye for eye, tooth for tooth,” a favorite Bible verse of its proponents. As Garrett Fagan writes in The Lure of the Arena: Social Psychology and the Crowd at the Roman Games, “the Romans were by no means alone in finding the sight of people and animals tormented and killed both intriguing and appealing.” The zest and delight that I witnessed among many of the death penalty proponents on the night of Otey’s execution was the same lust for death and mutilation expressed by the ancient Romans at the arena. That was an appetite that I didn’t want either my elected officials or my tax dollars feeding.

Just days after Otey’s execution, several dozen death penalty abolitionists and I gathered at a Lincoln church to mourn, console one another, and strategize. One woman, who had regularly visited Otey, challenged us to get to know people on death row so that those we were advocating for weren’t abstractions but individuals, each with a family, a hometown, a unique life story, and hopes for the future. In November, I met that challenge by joining eight or so members of Nebraskans Against the Death Penalty (NADP) on one of their semiannual visits to death row.

And what a challenge it was. In the days leading up to the visit, I was nervous. I’m very claustrophobic, so just the thought of being inside a prison left me wondering if I could even go through with it. And if I did, what would it be like to meet men who’d killed one or more people? And what to wear that would be appropriate? Professional? Business casual? Smart casual? Something more relaxed? Bright or somber? I chose a plain top, a comfortable cardigan, blue slacks, and Birkenstock sandals. Nothing provocative, nothing that might make me stand out in a crowd.

Much about entering the prison unnerved me, from the check-in at the front desk, where I left my keys, belt, and purse in a locker (I feel naked without my purse), to the simple pat down (I had to relinquish the antacid in my pocket). Our next stop was what I’d come to call the “holding cage,” a small room that was glassed and barred. After leaving the check-in and before being buzzed into the visitor’s room, we were locked behind those bars for what was probably only a minute or two but seemed like twenty. “This is where you feel like wetting your pants,” one of the other NADP-ers told me, the claustrophobic newbie, as the heavy door slid shut behind us.

In the visiting room, we waited for the inmates to arrive. I heard the other NADP-ers make small talk, but my thoughts were swirling and I was too busy looking around to fully join the conversation. In all of the crime shows I’d seen, Plexiglas separated the inmate and the visitor. I saw no such barrier here. General population inmates and their visitors sat in pairs, talking and eating junk food from the vending machines. The guard at the desk was armed. When the death row inmates arrived, I was nauseous and sweaty. Was this situation really safe? There were five of them, as half of those who were interested in visiting with NADP came to the first visit; the other half would come to the second visit on the next day. Four of the inmates were white, one was Native American, and all were in their thirties or forties. One wore civilian clothes; the others wore prison-issue tan pants, tan shirts, and white tennis shoes. Our visit was to last a couple of hours. How would I get through it? But when I saw the inmates and the NADP-ers hugging each other and how happy everyone was to see each other, I relaxed a bit.

We sat facing each other in two rows of immovable chairs. First, we conversed as a group, then in pairs or small groups, with each visitor moving from one seat to another so that we could talk to each inmate individually. This was as scary as entering the holding cage. What would I say to these men, each a convicted murderer, each living a life I couldn’t imagine? Was my life as foreign to them as theirs was to me? Would they see me as just another do-gooder or as someone here out of curiosity, a tourist who’d return to her free and comfortable life when the visit ended?

The inmates seemed experienced at talking to a first-timer, and I felt more at ease as we conversed about current events, legal processes, prison life, their childhoods, their families, and mine. And they quickly divested me of my naïve notions that the men on death row were so defeated and depressed by their experiences that they were nothing but numbers in the prison-industrial complex awaiting their turn to die in the electric chair, people who had much to gain by knowing me but nothing to give me in return. But I could see that in so many ways, these were just regular men. They worked out, played sports, and followed the news, and most stayed in touch with their families through visits, phone calls, and letters. What marked them as different from me and my friends was their knowledge of the law, the court system, the appeals process, the failures of the criminal justice system, and their lack of free movement. They lived behind a series of locked doors, none of which they had a key for. I would learn of other ways in which their lives differed from mine, chiefly that they would forever be judged and identified by the worst act of their lives.

I had participated in the death row visit as a duty, but I’d laughed and learned so much that I vowed to return for NADP’s spring visit. When it was time to leave, I, too, hugged the inmates.

During my first visit, Carey Dean Moore had not been at the Lincoln prison, as he was in Omaha for court proceedings regarding the legality of his death sentence. Fifteen years earlier, in 1979, he confessed that he had chosen his robbery and murder victims, Maynard Helgeland and Reuel Van Ness Jr., both forty-seven, because they were much older than him and so, he reasoned, easier to rob. In 1980, a three-judge panel chose a death rather than a life sentence because of the “exceptional depravity” aggravator set forth in the Nebraska Revised Statutes, which stated that first-degree murder was eligible for a death sentence if the killer’s actions were “so coldly calculated as to indicate a state of mind totally and senselessly bereft of all regard for human life.” In 1994, the Nebraska Supreme Court ruled that this aggravator was constitutionally vague “as written and constructed” and so vacated Carey’s death sentence. Then, the court redefined the phrase in question, “exceptional depravity,” as “cold, calculated planning of the victim’s death as exemplified by the purposeful selection of a particular victim on the basis of special characteristics.” As Carey chose Helgeland and Van Ness because of their age, his crimes now met the revised definition. On April 21, 1995, the state district court resentenced him to death. In May, when I visited death row for the second time, Carey Dean Moore was there.

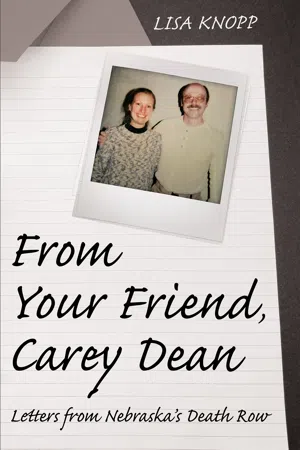

I was immediately drawn to him. He had intelligent, light blue eyes and short, thinning blond hair, was soft-spoken though intense, and had a stutter that would come and go. (“Stop stuttering,” he’d sternly tell himself, a command that he’d obey for awhile.) At thirty-seven, he was thirteen months younger than I. It was hard to believe that this man had ever done anything that met anyone’s definition of “exceptional depravity.” When he and I spoke individually, he asked the same questions as the other inmates had when we talked for the first time. Married? Yes. Kids? A daughter, Meredith, and a son, Ian. A job? I was an instructor at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, where I’d recently received my PhD. But in August, I’d start a position as an assistant professor of English at Southern Illinois University in Carbondale. My son from an earlier relationship would move with me; my husband and I would share the long-distance parenting of our daughter, which meant that she’d move back and forth between her two homes a couple of times each month. What I didn’t say was that we hoped that this arrangement would save our troubled marriage, a revelation that wasn’t appropriate to share with someone I’d just met.

When the conversation turned to Carey, he didn’t hold back. The first thing he told me about himself was unprompted: he had killed two people, he was guilty, and God had forgiven him. I had little experience talking with inmates and didn’t know how rare such an admission was. Then he asked me something that none of the others had: “Are you a Christian?”

This is a question that makes me uneasy. People can have very different ideas about what it means to be a Christian. “I am,” I answered warily.

“Praise God!” he exclaimed. “I am, too!”

We chatted about the church I belonged to. I told Carey th...