eBook - ePub

Valley Thunder

The Battle of New Market and the Opening of the Shenandoah Valley Campaign May, 1864

- 360 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Valley Thunder

The Battle of New Market and the Opening of the Shenandoah Valley Campaign May, 1864

About this book

An "exciting and informative" account of the Civil War battle that opened the 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign, with illustrations included (

Lone Star Book Review).

Charles Knight's Valley Thunder is the first full-length account in decades to examine the combat at New Market on May 15, 1864 that opened the pivotal Shenandoah Valley Campaign.

Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, who set in motion the wide-ranging operation to subjugate the South in 1864, intended to attack on multiple fronts so the Confederacy could no longer "take advantage of interior lines." A key to success in the Eastern Theater was control of the Shenandoah Valley, an agriculturally abundant region that helped feed Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. Grant tasked Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel, a German immigrant with a mixed fighting record, and a motley collection of units numbering some 10,000 men to clear the Valley and threaten Lee's left flank. Opposing Sigel was Maj. Gen. (and former US Vice President) John C. Breckinridge, who assembled a scratch command to repulse the Federals. Included in his 4,500-man army were Virginia Military Institute cadets under the direction of Lt. Col. Scott Ship, who'd marched eighty miles in four days to fight Sigel.

When the armies faced off at New Market, Breckinridge told the cadets, "Gentlemen, I trust I will not need your services today; but if I do, I know you will do your duty." The sharp fighting seesawed back and forth during a drenching rainstorm, and wasn't concluded until the cadets were inserted into the battle line to repulse a Federal attack and launch one of their own.

The Union forces were driven from the Valley, but would return, reinforced and under new leadership, within a month. Before being repulsed, they would march over the field at New Market and capture Staunton, burn VMI in Lexington (partly in retaliation for the cadets' participation at New Market), and very nearly capture Lynchburg. Operations in the Valley on a much larger scale that summer would permanently sweep the Confederates from the "Bread Basket of the Confederacy."

Valley Thunder is based on years of primary research and a firsthand appreciation of the battlefield terrain. Knight's objective approach includes a detailed examination of the complex prelude leading up to the battle, and his entertaining prose introduces soldiers, civilians, and politicians who found themselves swept up in one of the war's most gripping engagements.

Charles Knight's Valley Thunder is the first full-length account in decades to examine the combat at New Market on May 15, 1864 that opened the pivotal Shenandoah Valley Campaign.

Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, who set in motion the wide-ranging operation to subjugate the South in 1864, intended to attack on multiple fronts so the Confederacy could no longer "take advantage of interior lines." A key to success in the Eastern Theater was control of the Shenandoah Valley, an agriculturally abundant region that helped feed Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. Grant tasked Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel, a German immigrant with a mixed fighting record, and a motley collection of units numbering some 10,000 men to clear the Valley and threaten Lee's left flank. Opposing Sigel was Maj. Gen. (and former US Vice President) John C. Breckinridge, who assembled a scratch command to repulse the Federals. Included in his 4,500-man army were Virginia Military Institute cadets under the direction of Lt. Col. Scott Ship, who'd marched eighty miles in four days to fight Sigel.

When the armies faced off at New Market, Breckinridge told the cadets, "Gentlemen, I trust I will not need your services today; but if I do, I know you will do your duty." The sharp fighting seesawed back and forth during a drenching rainstorm, and wasn't concluded until the cadets were inserted into the battle line to repulse a Federal attack and launch one of their own.

The Union forces were driven from the Valley, but would return, reinforced and under new leadership, within a month. Before being repulsed, they would march over the field at New Market and capture Staunton, burn VMI in Lexington (partly in retaliation for the cadets' participation at New Market), and very nearly capture Lynchburg. Operations in the Valley on a much larger scale that summer would permanently sweep the Confederates from the "Bread Basket of the Confederacy."

Valley Thunder is based on years of primary research and a firsthand appreciation of the battlefield terrain. Knight's objective approach includes a detailed examination of the complex prelude leading up to the battle, and his entertaining prose introduces soldiers, civilians, and politicians who found themselves swept up in one of the war's most gripping engagements.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Valley Thunder by Charles R. Knight in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Breadbasket of the Confederacy

In late April 1864, Kit Hanger of Augusta County, Virginia, wrote a letter to her cousin in North Carolina. “We are expecting a large fight to come of[f] in the Valley,” she explained, “and I dread it very mutch [sic].”1 Her fears proved well founded. On the day that she wrote her cousin, a Union army was moving into the northern end of the Shenandoah Valley. Its objective was the town of Staunton, the center of Hanger’s picturesque southern Shenandoah region.

In the spring of 1864, the Shenandoah Valley was still a vibrant farming community. Although the area had already felt the hard hand of war, and thousands of its sons were in the ranks of the Southern army, its farms still produced supplies for the war effort. As long as Confederate troops occupied the region, those supplies would continue to flow. And as long as those troops were there in some strength, they were a threat to launch a raid into Pennsylvania, Maryland, or West Virginia, or to harass the right (western) flank of the Union Army of the Potomac operating across the Blue Ridge Mountains in north-central Virginia.

The onset of 1864 brought a new general to Washington, with a new strategy designed to break the back of the Confederacy and end the war for good. It would be for future historians to debate exactly when and where it had occurred, but for many in the South it was becoming apparent by the beginning of 1864 that the winds of war had shifted and no longer favored the Confederacy. “Our affairs look gloomy, very gloomy,” concluded a pessimistic Augusta County resident.2

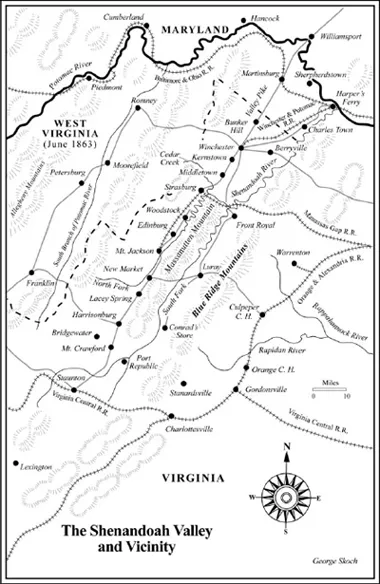

The Shenandoah Valley is nestled between the Blue Ridge Mountains to the east and the Alleghenies to the west. Approximately 125 miles in length, the Valley is one of the most productive agricultural regions in the South. Drained by and named for the Shenandoah River, which rises between Staunton and Lexington and flows northward to its confluence with the Potomac River at Harpers Ferry, the geography of the region is the source for some peculiar local terminology. Because the river flows from south to north, the northern end is referred to as the “lower” Valley, and the southern end as the “upper” Valley. Thus, moving north is to go “down” the Valley, and traveling south is moving “up” the Valley.

Neatly bisecting the central Valley is the massive Massanutten Mountain. While its name implies a single peak, it is in reality a series of ridges nearly 50 miles long, stretching from Harrisonburg in the south to Front Royal at its northern end. The area to the west of the Massanutten is known as the Shenandoah Valley proper, and through which flows the river’s North Fork. (The North and South Fork of the Shenandoah combine near Front Royal.) The Valley east of the Massanutten is somewhat narrower and is drained by the South Fork of the Shenandoah. This section of the valley is known as the Page or Luray Valley. The mountain is passable only at its center, where a turnpike connects New Market on the west to Luray on the east through New Market Gap. A smaller depression in the Massanutten itself, known as Fort Valley, extends northward from the gap. Samuel Kercheval, author of the first history of the Shenandoah Valley, described Massanutten as “something of the shape of the letter Y, or perhaps more the shape of the houns and tongue of a wagon.”3 A small tollhouse stood at the crest of New Market Gap, explained one historian of the region, “from which each of the valleys of the North and South [Forks of the Shenandoah] present to the delighted vision of the traveler a most enchanting view of the country for a vast distance. The little thrifty village of New Market, with a great number of farms … are seen in full relief” at the western base.4

The Valley had perhaps one of the best roads in the entire country at the time of the Civil War. The Valley Pike, one of only a handful of hard-surface roads in Virginia, connected Staunton with Martinsburg. The Pike, with its macadamized (mainly gravel) surface, was completed about 1840 and could be traversed in virtually all weather, when rains turned other dirt roads into almost impassable quagmires. Toll booths were situated along the Pike every five miles.5

Several railroads connected the Valley with eastern Virginia. The Virginia Central Railroad had its terminus just west of Staunton and served as the major supply link with the Confederate capital of Richmond. The Virginia & Tennessee Railroad, though not in the Shenandoah Valley itself, passed through the mountains of southwestern Virginia, connecting its two namesake states. In the lower Valley, the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad followed the Potomac, connecting Washington and Baltimore with points west. For most of its length, the railroad was on the Maryland side of the river, but it crossed to the southern shore at Harpers Ferry and continued on to Martinsburg and into what is now West Virginia. A spur of the B&O ran south into Winchester. Also paralleling the Potomac was the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal, another vital east-west link. The Manassas Gap Railroad crossed into the Valley east of Front Royal and stretched as far south as Mount Jackson. While these railroads and the canal provided several reliable east-west routes, no continuous north-south railroad existed in the Valley. The Valley Pike, along with several lesser roads, provided the only means of travel up and down the scenic region.

The Valley was as fertile as it was beautiful in the early 1860s. It was those qualities that had first drawn settlers to the region a century earlier. Most of the original settlers—many of them German or Scotch-Irish—migrated south from Pennsylvania, following the greater valley system of which the Shenandoah is but a part. By the 1860s, large farms, not plantations as in the deep South but sizeable nonetheless, populated the area. So plentiful were the harvests that the Valley would be known during the Civil War years as the “Breadbasket of the Confederacy.” The region also had several small iron furnaces, which provided the raw materials used by the railroads before the war, and artillery and other articles of war after 1861. Beyond the southern extremities of the Valley in southwest Virginia were lead and salt mines, which would produce most of the Confederacy’s supply of these important materials. An early historian of the Valley described it as “Beautiful to look upon, and so fertile that it was styled the granary of Virginia, rich in its well-filled barns, its cattle, its busy mills, the Valley furnished from its abundant crops much of the subsistence of Lee’s army.”6

The Valley was mostly anti-secessionist in sentiment in 1861, though for the most part its citizens remained loyal to Confederate interests once Virginia seceded. (The northwestern counties of Virginia, by way of contrast, separated to form the state of West Virginia in 1863.) While there were some slaves in the region, the numbers did not approach those of Tidewater Virginia. Valley farms were largely worked by the families themselves, and the supplies they furnished the Confederacy fed the Army of Northern Virginia.

The military significance of the Shenandoah Valley was readily apparent in 1861 to authorities in both Richmond and Washington. Confederate forces, initially commanded by Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, had been concentrated at Harpers Ferry to resist any Federal incursion. As an invasion route, the Valley favored the Confederacy. Running southwest to northeast, it pointed directly into the heart of Pennsylvania and Maryland—with the northern (lower) end of the Valley spilling out north of Washington, D.C—with the opposite end deflecting any Union advance up the Valley away from Richmond. The several gaps in the mountains that allowed access to the Valley could be defended by small numbers of troops, which could screen the movements of a larger body of men operating in the Valley proper.

In the spring of 1862, Jackson frustrated attempts by three separate Union columns to capture the region. In the process, he raised alarm in the Northern capital in general, and with President Abraham Lincoln in particular. The Union commander-in-chief was worried that Jackson might attempt a direct attack upon the capital. As a result, Lincoln decided to shift large numbers of troops to the city’s defenses instead of to the front where they were originally intended to be employed.

Later in 1863, Robert E. Lee led his Army of Northern Virginia through the Valley to begin his invasion of the North. His movements and intentions were well masked until he overwhelmed a Union garrison at Winchester in mid-June. After the defeat at Gettysburg, Lee retired into the Valley to rest and resupply his army, as he had done after his first invasion into Maryland had been turned back at Sharpsburg the previous year.

The vast amount of territory and the disproportionate number of troops assigned to it made the region a nightmare for Union commanders and a haven for guerrillas and bushwhackers. Cavalry raids routinely targeted the railroads, especially the B&O line. Residents of the lower Valley would sometimes wake up to discover their homes well within the lines of one army, and by nightfall be occupied by the other side, only to find change again the following day. Winchester, the road hub of the lower Valley, changed hands during the war an estimated 72 times—more than any other town in American history.7

During the winter of 1863-64, Ulysses S. Grant was named General in Chief of the Union armies. Grant had amassed an impressive war record. His capture of Forts Henry and Donelson in Tennessee in early 1862 provided the North with its first major field victories. Two months later, Grant absorbed a stunning Confederate surprise attack at Shiloh on April 6 that nearly pushed his army into the Tennessee River, reorganized his men, and drove the enemy from the field the following day. Although many in and out of the army questioned his fitness to command because of his reputed fondness for the bottle, Grant had become a favorite of President Lincoln because of his aggressive nature in the field. From late 1862 through the summer of 1863, Grant worked tirelessly to capture Vicksburg, the last Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi River. His daring plan to cross the river below the city, move inland, and attack it from the east was successful, and the city (and its defending army) surrendered on July 4, 1863. Later that fall in October and November, Grant assumed command in Tennessee. After careful preparation he attacked, knocking the Confederate Army of Tennessee into northern Georgia and lifting the siege of Chattanooga. This impressive string of victories convinced Lincoln that Grant was the man who could draw up and execute the blueprint for final victory.

When word of Grant’s appointment reached Richmond, most of the fighting men in gray were not impressed. Lieutenant Colonel Walter H. Taylor, an officer on Lee’s staff, expressed a view shared by many: “I do not think he [Grant] is to be feared. He has been much overrated and in my opinion … owes more of his reputation to … bad management [by his opponents] than to his own sagacity and ability.” Taylor predicted that Grant “will shortly come to grief” because of the different caliber of commanders he would be facing in the east.8

Grant did not assume new responsibilities unprepared. To date, there had been no overall strategy employed by the Union high command. Instead, each army had operated more or less independently in its respective theater, with little or no cooperation from other forces. This policy, or lack thereof, had allowed the Confederates to shift troops from one threatened area to another. Like the man, Grant’s plan was relatively simple: a simultaneous advance by all Union armies, with the destruction of their rival Confederate forces as their main goal, rather than the mere occupation of territory. Territorial conquest and occupation would be a by-product of crippling Confederate forces.

The actual execution of Grant’s plan would be three-fold. Major General William T. Sherman would advance into Georgia against the Army of Tennessee. Major General Nathaniel Banks would lead a movement into Louisiana and southern Arkansas to finish off Confederate resistance west of the Mississippi River. In Virginia, Grant would oversee the operations of Major General George G. Meade’s Army of the Potomac against its old adversary, Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia, traveling with the army rather than remaining in the capital.

To support Meade’s advance, Grant planned for two smaller armies to operate on his flanks to further threaten Lee and divert enemy troops away from Meade. To the east, the newly formed Army of the James would advance up the Virginia peninsula between the James and York rivers. This army, commanded by Major General Benjamin F. Butler, was tasked with threatening Richmond or Petersburg (the latter a major supply center and transportation hub) in an effort to compel Lee to divide his army. To the west in the mountains of western Virginia, a smaller command would tie down Confederates to prevent them from moving to reinforce Lee and also sever rail connections and deny Lee supplies coming from the Valley and southwestern Virginia.

In February 1864, the Federal Department of West Virginia was commanded by Brigadier General Benjamin F. Kelley, a former colonel of the 1st Virginia Infantry, one of the three-month regiments that flocked to the Union Army in 1861. After the enlistments expired, Kelley was given more responsibility. His new command included all of West Virginia as well as portions of Maryland and Virginia, including the lower (northern) Shenandoah Valley. It was a sizeable area, with somewhat fluid borders, encompassing whatever was occupied and could be held by Union forces. Through Kelley’s new command passed the B&O Railroad and the C&O Canal, and his garrison was responsible for guarding against incursions into Pennsylvania, in addition to protecting key points within the department. However, the number of troops under his command was totally inadequate for the task. Confederate cavalry as well as bands of guerillas raided railroads often with impunity, damaging the track, bridges, support facilities, and the trains themselves, in addition to cutting telegraph wires and intercepting wagon trains and capturing their guards. Because of the limited resources at his disposal, Kelley was hard pressed to do anything but react to the raids as they occurred. In describing how Union efforts had fared in the Valley, one historian observed they “had yielded so many captures of Union garrisons and so many disasters in the field, as to be called the Valley of Humiliation.”9 West Virginia was anything but a desirable command.

During one raid in early February, Confederate cavalry managed to capture Brigadier General Eliakim Scammon, one of Kelley’s subordinates, along with several of his staff and a small escort. Days later the West Virginia legislature passed a resolution denouncing Kelley for his inability to stop the raids and called upon Washington to replace him.10 While Kelley co...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Frontmatter1

- Contents

- Maps

- Frontmatter2

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1: The Breadbasket of the Confederacy

- Chapter 2: Fighting Mit Sigel

- Chapter 3: “We are in for business now”

- Chapter 4: Into the Valley of Defeat

- Chapter 5: “We will give them a warm reception”

- Chapter 6: “Hold New Market at all hazards”

- Chapter 7: “We can whip them here”

- Chapter 8: “Are they driving us?”

- Chapter 9: “I felt so confident of success”

- Chapter 10: “Fame!”

- Appendix 1: Order of Battle at New Market (with strengths)

- Appendix 2: After-Action Battle Reports for John C. Breckinridge (CSA) and Franz Sigel (USA)

- Appendix 3: The 54th Pennsylvania Infantry at New Market

- Appendix 4: The Bushong family, George Collins, and New Market Battlefield State Historical Park

- Appendix 5: The Role of the 23rd Virginia Cavalry at New Market

- Appendix 6: Breckinridge, Imboden, and the Confederate Flanking Operation East of Smith’ s Creek

- Appendix 7: John C. Breckinridge and the “Shell-struck Post”

- Appendix 8: Where Woodson’ s Heroes Fell: The 1st Missouri Cavalry at New Market

- Footnotes

- Bibliography

- About the author