eBook - ePub

Protecting the Flank at Gettysburg

The Battles for Brinkerhoff's Ridge and East Cavalry Field, July 2 -3, 1863

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Protecting the Flank at Gettysburg

The Battles for Brinkerhoff's Ridge and East Cavalry Field, July 2 -3, 1863

About this book

The award-winning Civil War historian's study "makes the case that Union cavalry had a tremendous effect on the course of the titanic battle" (J. David Petruzzi, author of

The Complete Gettysburg Guide).

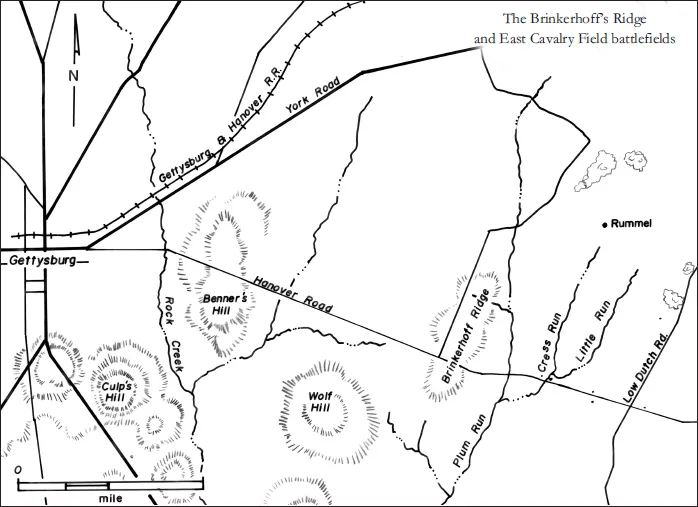

On July 3, 1863, a large-scale cavalry fight was waged on Cress Ridge four miles east of Gettysburg. There, on what is commonly referred to as East Cavalry Field, Union horsemen under Brig. Gen. David M. Gregg tangled with the vaunted Confederates riding with Maj. Gen. Jeb Stuart. This magnificent mounted clash, however, cannot be fully appreciated without an understanding of what happened the previous day at Brinkerhoff's Ridge, where elements of Gregg's division pinned down the legendary infantry of the Stonewall Brigade, preventing it from participating in the fighting for Culp's Hill that raged that evening.

After arriving at Gettysburg on July 2 and witnessing the climax of the fighting at Brinkerhoff's Ridge, Stuart knew that if he could defeat Gregg's troopers, he could dash thousands of his own men behind enemy lines and wreak havoc. The ambitious offensive thrust resulted the following day in a giant clash of horse and steel on East Cavalry Field. The combat featured artillery duels, dismounted fighting, hand-to-hand engagements, and the most magnificent mounted charge and countercharge of the entire Civil War.

This fully revised edition of Protecting the Flank at Gettysburg is the most detailed tactical treatment of the fighting on Brinkerhoff's Ridge yet published, and includes a new Introduction, a detailed walking and driving tour with GPS coordinates, and a new appendix refuting claims that Stuart's actions on East Cavalry Field were intended to be coordinated with the Pickett/Pettigrew/Trimble attack on the Union center on the main battlefield.

On July 3, 1863, a large-scale cavalry fight was waged on Cress Ridge four miles east of Gettysburg. There, on what is commonly referred to as East Cavalry Field, Union horsemen under Brig. Gen. David M. Gregg tangled with the vaunted Confederates riding with Maj. Gen. Jeb Stuart. This magnificent mounted clash, however, cannot be fully appreciated without an understanding of what happened the previous day at Brinkerhoff's Ridge, where elements of Gregg's division pinned down the legendary infantry of the Stonewall Brigade, preventing it from participating in the fighting for Culp's Hill that raged that evening.

After arriving at Gettysburg on July 2 and witnessing the climax of the fighting at Brinkerhoff's Ridge, Stuart knew that if he could defeat Gregg's troopers, he could dash thousands of his own men behind enemy lines and wreak havoc. The ambitious offensive thrust resulted the following day in a giant clash of horse and steel on East Cavalry Field. The combat featured artillery duels, dismounted fighting, hand-to-hand engagements, and the most magnificent mounted charge and countercharge of the entire Civil War.

This fully revised edition of Protecting the Flank at Gettysburg is the most detailed tactical treatment of the fighting on Brinkerhoff's Ridge yet published, and includes a new Introduction, a detailed walking and driving tour with GPS coordinates, and a new appendix refuting claims that Stuart's actions on East Cavalry Field were intended to be coordinated with the Pickett/Pettigrew/Trimble attack on the Union center on the main battlefield.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Protecting the Flank at Gettysburg by Eric J. Wittenberg in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Prelude to Battle

Brigadier General David M. Gregg watched as the Second Division of the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps rode past. Little escaped his critical eye. His men and horses were exhausted, but duty called. A day earlier, John Buford’s cavalry had opened a battle in Pennsylvania. Gregg’s men were needed.

Gregg’s tired horse soldiers had spent nearly four solid days in the saddle by the morning of July 2, 1863, but they still had not reached Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. They had crossed the Potomac River at Edwards Ferry on June 27 and made their way through Maryland in intense heat, with clouds of dust billowing along their line of march. Worn-out horses dropped from over-exertion, and dismounted cavalrymen, new members of the dreaded “Company Q,” trudged along carrying their saddles and bridles in the hope of finding new mounts. Some succeeded, but most plodded along through the suffocating heat and thick dust. Others, whose horses were too worn out to keep up, brought up the rear with the division’s mule train.1

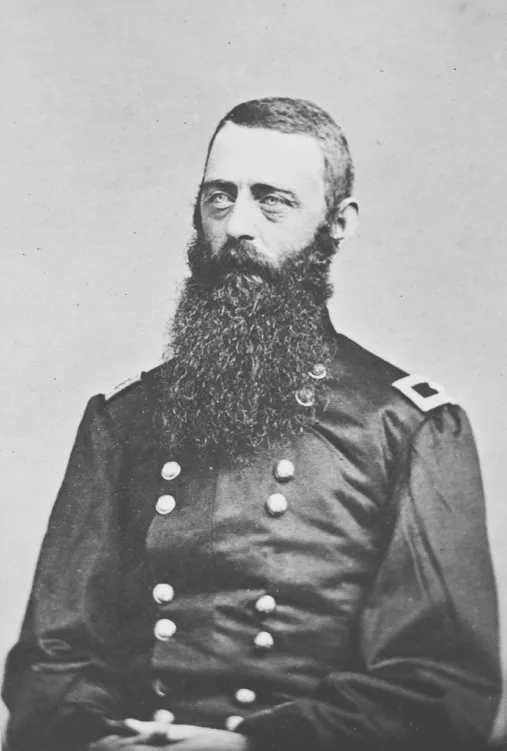

Brig. Gen. David M. Gregg.

Library of Congress

The 30-year-old Gregg was the first cousin of Pennsylvania Governor Andrew G. Curtin and especially determined to defend the soil of his home state. He was a career cavalryman. After graduating from West Point in 1855, Gregg served with the First Dragoons along the southwestern frontier and, with the coming of war, received an appointment as captain in the newly formed 6th U.S. Cavalry. On January 24, 1862, he accepted a commission as colonel of the 8th Pennsylvania Cavalry and received a promotion to brigadier general of volunteers on November 29, 1862.2

The Union cavalry commander was “tall and spare, of notable activity, capable of the greatest exertion and exposure; gentle in manner but bold and resolute in action. Firm and just in discipline he was a favorite of the troopers and ever held, for he deserved, their affection and entire confidence.” Gregg understood the principles of war and was skilled in their application. Endowed “with a natural genius of high order, he [was] universally hailed as the finest type of cavalry leader. A man of unimpeachable personal character, in private life affable and genial but not demonstrative, he fulfilled with modesty and honor all the duties of the citizen and head of an interesting and devoted family.” Modesty prevented Gregg from receiving full credit for his many contributions to the development of the Union cavalry, but the troopers knew him to be “brave, prudent, dashing when occasion required dash, and firm as a rock. He was looked upon both as a regimental commander and afterwards as Major-General, as a man in whose hands any troops were safe.”3 The second and third days of the battle of Gettysburg marked Gregg’s most important contribution to the Army of the Potomac.

On July 1 Gregg received orders to leave Col. Pennock Huey’s brigade to occupy Westminster, Maryland, “for the purpose of guarding the rear of the army and protecting the trains which were to assemble” there.4 Gregg left Huey’s 1,400 troopers and Lt. William D. Fuller’s Battery C, 3rd U.S. Artillery at Westminster and continued toward Gettysburg. His two remaining brigades were further weakened by the detachment of the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry and the 1st Pennsylvania Cavalry. The Massachusetts troopers had been shredded at Aldie two weeks earlier on June 17, and were now escorting the Army of the Potomac’s Sixth Corps headquarters, while the Pennsylvania horsemen served as the escort for the army’s Artillery Reserve.

“The day’s march was a terrible one; the heat most intense and unendurable,” recalled a Marylander about the division’s travails on July 1. “Scores of horses fell by the roadside. Dismounted cavalrymen whose horses had fallen struggled along, carrying saddles and bridles, hoping to buy or capture fresh mounts. Every energy was strained in the one direction where they knew the enemy was to be found.” Inexperienced artillerists of the 3rd Pennsylvania Heavy Artillery, who had just been attached to Gregg’s command a couple of days earlier, begged to be allowed to rest and find something to eat; their imploring cries were ignored.5

Gregg’s two remaining brigades reached Hanover, Pennsylvania, near midnight on July 1, where they quickly spotted evidence of a cavalry battle that had raged there the previous day. “The streets were barricaded and dead horses lay about in profusion,” reported hospital steward Walter Kempster of the 10th New York. Gregg roused local residents to ascertain the way to Gettysburg and to find out what had happened in the streets of the town the day before. “By this time we had become a sorry-looking body of men,” recorded an officer of the 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry, “having been in the saddle day and night almost continuously for over three weeks, without a change of clothing or an opportunity for a general wash; moreover we were much reduced by short rations and exhaustion, and mounted on horses whose bones were plainly visible to the naked eye.”6

After a brief rest, Gregg’s 2,600 troopers remounted and struck out to the southwest on the Littlestown Road. The horsemen navigated their way through the inky blackness, while many men fell asleep in the saddle. Periodically, a dozing trooper fell to the ground with an undignified crash, halting the column until the rudely awakened man could be coaxed back onto his mount. And so they slowly made their way across the sleeping countryside, the silence broken only by clopping hoof beats. General Gregg and his staff rode ahead, hoping to find headquarters and obtain orders. They arrived at Army of the Potomac’s headquarters about noon. After some discussion, Gregg received order to take his division to the far right flank of the army’s position.7

As the Second Division made its way along the Littlestown Road, a lone rider dashed past the marching column. Dr. Theodore T. Tate, an assistant surgeon with the 3rd Pennsylvania, had lived in Gettysburg before the war broke out, and so he knew the local road network. The doctor found General Gregg and informed him that there was a shorter route available. Within a short time he was leading the men across fields toward McSherrystown. Passing St. Joseph’s Academy, Tate turned the column onto the Hanover Road, which ended in Gettysburg ten miles distant. The sound of guns booming to the west spurred the weary horse soldiers on. After nine hard hours in the saddle, the column reached the intersection of the Hanover and Low Dutch roads, an important crossroads about three miles from the town square. It was about noon on July 2.

“Reaching the height, some three miles east of the village, about noon, the Regiment halted and dismounted on the south side of the Hanover Road,” reminisced Lt. Noble D. Preston, the 10th New York Cavalry’s capable commissary officer. “A rail fence on the opposite side of the road was leveled to give free passage for mounted troops. This had an ominous look and chilled the ardor of some of the men.”8

One trooper remembered losing his horse on the long hard ride and then catching up with his command about this time. “On the march from Hanover my horse gave out, and I left him with a farmer,” explained a sergeant from the 10th New York Cavalry. “When I reached the Regiment it was lying on the left of the Hanover Road, near the cross roads. I obtained permission from Major [Matthew] Avery [commander of the 10th New York] to go to the front, where I hoped to pick up a horse.”9

“Soon after noon we arrived near the battlefield of Gettysburg, via the Hanover pike,” recalled Capt. George Lownsbury of the 10th New York. “We had been sitting on our horses and lying on the ground on the left of the turnpike all afternoon until near sundown.” The New Yorkers knew this ground well. The regiment had spent seventy-two days in Gettysburg in 1861 training and learning the art of war. They had drilled on the very fields where they now lay sprawled. A few of their comrades rested in nearby Evergreen Cemetery, the first victims of the Civil War to be interred in Gettysburg.10

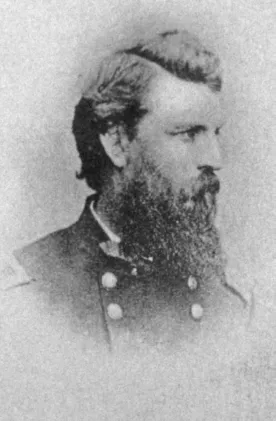

Not long thereafter, Col. J. Irvin Gregg, Brig. Gen. David Gregg’s first cousin and commander of the Second Brigade, received orders to ride down the Low Dutch Road to its junction with the Baltimore Pike. Like his younger cousin, 37-year-old Irvin Gregg was a quiet and competent cavalryman. Unlike the general, however, the elder Gregg was not a professional soldier. When war broke out with Mexico in 1846, he enlisted in a Pennsylvania volunteer infantry regiment and quickly became an officer. After honorable service Gregg returned to the iron foundry he owned in Pennsylvania. When the Civil War broke out in 1861, he joined his cousin David in the newly formed 6th U.S. Cavalry with a captain’s commission. In November of 1862 he was appointed colonel of the 16th Pennsylvania Cavalry, and served with distinction with that command. In the spring of 1863, he assumed command of a veteran brigade with a well-earned reputation for being “steadfast” and “cool as a clock, looking out from under his broad slouch hat on any phase of battle.” The troopers referred to the very tall Irvin Gregg as “Long John.”11

After the men wheeled onto the Low Dutch Road, the order to proceed was countermanded and Colonel Gregg turned his command around. Infantry of the Army of the Potomac’s Fifth Corps blocked the cavalrymen’s route, and the horse soldiers were forced to countermarch across farm fields to get back to the intersection of the Hanover and Low Dutch roads. They would not return until nearly three that afternoon. One of Gregg’s regiments, the 4th Pennsylvania Cavalry, received orders to cover the army’s left flank after the withdrawal of Brig. Gen. John Buford’s First Cavalry Division, and did not return until later that evening.12

Col. J. Irvin Gregg, commander, Third Brigade, Second Cavalry Division.

USAHEC

Another one of Gregg’s regiments, the 16th Pennsylvania Cavalry, “marched down to the right of the main line—to occupy a gap and do Sharpshooting-at long range, with our Carbines,” wrote a sergeant. “We soon attracted attention, and later an occasional shell fell conspicuously close— but far enough to the rear of us so we suffered no serious harm.” By noon, these men were drawing constant enemy fire from several different directions and spent the balance of the afternoon supporting the Federal infantry holding the army’s far right flank near Wolf’s Hill.

The Pennsylvanians had a clear view of the day’s fighting. “The general battle increased in energy—and occasional fierceness,” recalled the sergeant, “and by 2 p.m., the cannonading was most terrific and continued til 5 p.m. and was inters...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Other Books by Eric J. Wittenberg

- Contents

- Preface to the 2002 Edition

- Preface to the 2013 Edition

- Foreword

- Chapter 1 : Prelude to Battle

- Chapter 2 : The Battle for Brinkerhoff's Ridge

- Chapter 3 : The Fight for the Rummel Farm

- Chapter 4 : The Battle for East Cavalry Field

- Conclusion : The Union Cavalry's Finest Hour

- Appendix A Order of Battle: Brinkerhoff's Ridge

- Appendix B Order of Battle: East Cavalry Field

- Appendix C : What was Jeb Stuart's Mission on July 3, 1863?

- Appendix D : Which Confederate Battery Fired Four Shots?

- Appendix E : Driving Tour: The Battles for Brinkerhoff's Ridge and East Cavalry Field

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author