eBook - ePub

Fight Like the Devil

The First Day at Gettysburg, July 1, 1863

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Fight Like the Devil

The First Day at Gettysburg, July 1, 1863

About this book

"Gives the reader an excellent readable narrative of the first day of battle . . . [and] an incredible driving tour which closes each chapter." —Matthew Bartlett,

Gettysburg Chronicle

Do not bring on a general engagement, Confederate General Robert E. Lee warned his commanders. The Army of Northern Virginia, slicing its way through south-central Pennsylvania, was too spread out, too vulnerable, for a full-scale engagement with its old nemesis, the Army of the Potomac. Too much was riding on this latest Confederate invasion of the North. Too much was at stake.

As Confederate forces groped their way through the mountain passes, a chance encounter with Federal cavalry on the outskirts of a small Pennsylvania crossroads town triggered a series of events that quickly escalated beyond Lee's—or anyone's—control. Waves of soldiers materialized on both sides in a constantly shifting jigsaw of combat. "You will have to fight like the devil . . ." one Union cavalryman predicted.

The costliest battle in the history of the North American continent had begun.

July 1, 1863 remains the most overlooked phase of the battle of Gettysburg, yet it set the stage for all the fateful events that followed.

Bringing decades of familiarity to the discussion, historians Chris Mackowski, Kristopher D. White, and Daniel T. Davis, in their always-engaging style, recount the action of that first day of battle and explore the profound implications in Fight Like the Devil.

"The book, written in the series' accessible style, includes more than 100 illustrations, new maps and analysis." — Longwood Magazine

Do not bring on a general engagement, Confederate General Robert E. Lee warned his commanders. The Army of Northern Virginia, slicing its way through south-central Pennsylvania, was too spread out, too vulnerable, for a full-scale engagement with its old nemesis, the Army of the Potomac. Too much was riding on this latest Confederate invasion of the North. Too much was at stake.

As Confederate forces groped their way through the mountain passes, a chance encounter with Federal cavalry on the outskirts of a small Pennsylvania crossroads town triggered a series of events that quickly escalated beyond Lee's—or anyone's—control. Waves of soldiers materialized on both sides in a constantly shifting jigsaw of combat. "You will have to fight like the devil . . ." one Union cavalryman predicted.

The costliest battle in the history of the North American continent had begun.

July 1, 1863 remains the most overlooked phase of the battle of Gettysburg, yet it set the stage for all the fateful events that followed.

Bringing decades of familiarity to the discussion, historians Chris Mackowski, Kristopher D. White, and Daniel T. Davis, in their always-engaging style, recount the action of that first day of battle and explore the profound implications in Fight Like the Devil.

"The book, written in the series' accessible style, includes more than 100 illustrations, new maps and analysis." — Longwood Magazine

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fight Like the Devil by Chris Mackowski,Christopher D. White,Daniel T. Davis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Wednesday, June 28, 1865

From Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade, commander of the Army of the Potomac:

Soldiers: This day, two years [ago], I assumed command of you, under the order of the President of the Unites States. To-day, by virtue of the same authority, this army [is] ceasing to exist, I have to announce my transfer to other duties, and my separation from you.

It is unnecessary to enumerate here all that has occurred in these two eventful years, from the grand and decisive Battle of Gettysburg, the turning point of the war, to the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House. Suffice it to say that history will do you justice, a grateful country will honor the living, cherish and support the disabled, and sincerely mourn the dead. . . .

General Order No. 35 did what the Army of Northern Virginia could never do: it finished off, once and for all, the Army of the Potomac.

Meade, the army’s commander, bid his men farewell in the same professional tone he had used two years earlier when he first assumed command. That June 28— 1863—stood in stark contrast to the celebratory mood that buoyed the postwar country. On that former date, in the midst of an uncertain military campaign, Meade became the fourth general in eight months to command President Lincoln’s principal army.

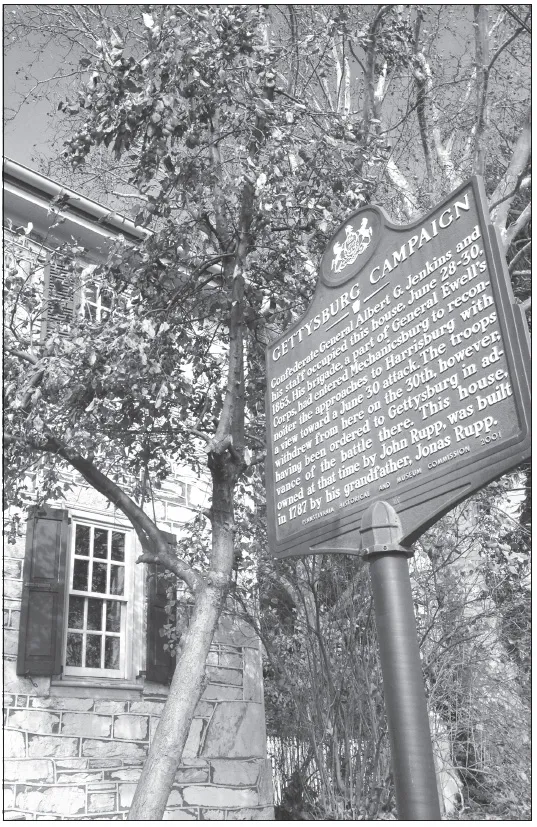

Confederate forces reached Mechanicsburg, just a few miles from the state capital. (cm)

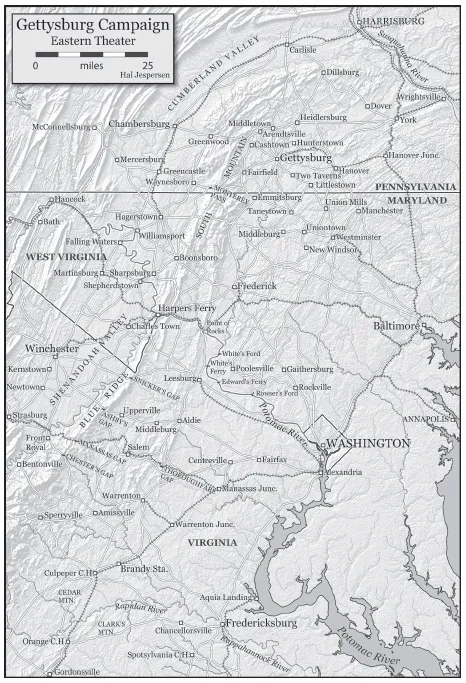

GETTYSBURG CAMPAIGN—For the first two years of the war, most of the fighting had shifted back and forth in the 100-mile corridor between Washington, D.C., and Richmond. Lee had tried to take his Confederate army northward once before, in the fall of 1862 but was turned back along Antietam Creek in Maryland. In the summer of 1863, many reasons drove Lee to decide on a second northern invasion.

Since November 1862, the fighting men of the Army of the Potomac had endured innumerable letdowns. On November 7, their beloved commander, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, was relieved of command. His replacement, Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside, lasted a mere 77 days in command of the army. Mother Nature, Washington politics, and Lee’s army ruined Burnside’s “On to Richmond” campaign, low-lighted by the lopsided December loss at Fredericksburg.

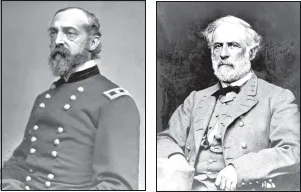

The “goggle-eyed snapping turtle,” Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade (left) and “the Gray Fox,” Gen. Robert E. Lee (right) (loc)

Burnside’s replacement was his arch nemesis, Maj. Gen. Joseph “Fighting Joe” Hooker. As Hooker assumed command in January of 1863, the army’s morale was dangerously low. “This winter is, indeed, the Valley Forge of the war,” wrote Lt. Col. Rufus Dawes of the 6th Wisconsin. But Hooker brought with him sorely needed elan and éven arrogance. He reorganized the army, restored its morale, and then marched it into the Wilderness of Spotsylvania County—where he bungled a two-to-one advantage to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory at the battle of Chancellorsville.

Meade, by then commander of the Federal V Corps, watched in impotent frustration as Hooker ordered his men to give up advantages they had gained on the first day of that battle. “My God, if we can’t hold the top of a hill, we certainly cannot hold the bottom of it!” he fumed. For the rest of the battle, his corps remained unengaged. After the battle, Meade’s deflation was palpable: “General Hooker has disappointed all his friends by failure to show his fighting qualities at the pinch.”

“Fighting Joe” Hooker first lost to Lee at Chancellorsville then picked a fight with his boss, General-in-Chief Henry Halleck. He lost that one, too —thus becoming the latest in a long string of generals to get removed from command of the Army of the Potomac. Meade would replace him. (loc)

The string of Federal commanders was due, in no small part, to the string of victories Gen. Robert E. Lee had amassed. After taking over Confederate forces in June, 1862, he had driven the Army of the Potomac from the gates of Richmond in the Seven Days battles and then moved on to victory at Second Manassas. In September, he fought McClellan’s much larger army to a bloody draw on the banks of Antietam Creek, and in December, he stopped Burnside cold. The victory at Chancellorsville in May of 1863 sealed his reputation.

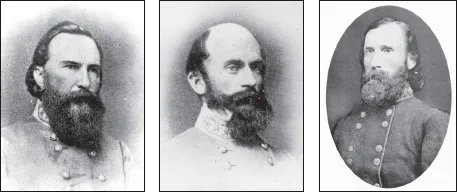

In the wake of the mortal wounding of Stonewall Jackson, Robert E. Lee reorganized the Army of Northern Virginia into three corps from two. Lt. Gen. James Longstreet (left) commanded the First Corps; Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell (center) commanded the Second Corps; and Lt. Gen. A. P. Hill (right) commanded the Third Corps. Lee depended heavily on Longstreet and called him “my old War Horse.” Ewell and Hill had both performed exceptionally well as division commanders but remained untested at the corps level. Gettysburg would be Lee’s first time employing his new command structure in battle; his learning curve would prove costly. (nps)

“He sat in the full realization of all that soldiers dream of—triumph,” wrote Lee’s staff officer, Charles Marshall. “I thought that it must have been from such a scene that men in ancient times rose to the dignity of gods.”

Chancellorsville had been a costly victory for Lee, though. Out of the nearly 60,000 Confederate soldiers engaged, 13,460 names lined the casualty rolls. Of Lee’s 130 regimental commanders, 64 had been killed, wounded, or captured. The Army of Northern Virginia also lost nine general officers, and while many of them would recover from their wounds to fight another day, one important general would not: Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson. Accidentally wounded by his own men on May 2, Jackson died of pneumonia on May 10.

Undaunted by his losses, Lee reorganized his army on May 6, and by May 14, he was in Richmond, urging Confederate President Jefferson Davis and Secretary of War James Seddon to allow him to press the war northward across the Mason-Dixon Line.

Lee hoped to accomplish many goals in pushing the war across the Potomac River. Northern Virginia had been ravaged by the hard hand of war, and by moving north, Lee planned to obtain supplies in Maryland and Pennsylvania, while his army lived off the lush countryside, thus allowing the Virginia farmers to harvest crops without the opposing army’s trampling over them.

A Confederate victory on northern soil also might still attract European intervention, although the battle at Antietam had made such intervention a long shot. By going into Pennsylvania, Lee also hoped to sow panic, discontent, and disruption throughout the North. That, in turn, might influence the fall Congressional elections.

Davis gave Lee the okay, and on June 3, the Army of Northern Virginia began what would become the most famous campaign of the war.

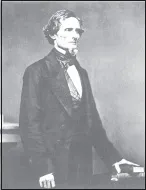

Confederate President Jefferson Davis (above) had been considering proposals to send a portion of the Army of Northern Virginia westward to aid the Confederate bastion at Vicksburg, Mississippi, where Union Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant was engaged in a campaign to crack that stronghold wide open. Lee had proven time and again that he could do more with less, so stripping away some of his veterans for use elsewhere seemed a viable option. No one thought to reinforce him. Lee was, in effect, a victim of his own success: He continued to find victory despite long odds, so why did he need help? Lee countered with his invasion plan, in part, as a way to keep his army intact. His northern offensive would help Vicksburg, he reasoned, because it would tie up any blue troops in the Eastern Theater from being sent west; in fact, threatening Washington, D.C., might draw troops from the West to bolster defenses in the East. (loc)

The weeks after Chancellorsville were arguably the darkest days of Fightin’ Joe’s life.

Politicians came to the army’s camps and listened to the complaints of their constituents—many of them leveled at Hooker. In response, Hooker took to finger-pointing, which curdled the already sour feelings of his senior officers, who soon broke out into open revolt.

Perhaps most bruising was Hooker’s diminished relationship with President Lincoln. The two had shared open, direct communication, but after Chancellorsville, Hooker was forced to communicate directly with the army’s General-in-Chief, Henry W. Halleck, a longtime foe. The mutual loathing between them soon erupted into bureaucratic warfare and then escalated into a power struggle. Ever the poker player, Hooker went all in on June 27: If he could not get his way, he asked to be relieved. “You have long been aware, Mr. President, that I have not enjoyed the confidence of the major-general commanding this army,” Hooker had pointed out, “and I can assure you so long as this continues, we may look in vain for success. . . .” Lincoln called Hooker’s bluff and accepted his resignation.

It could not have come at a more tenuous time. By the end of June, the Army of Northern Virginia had slipped away from the banks of the Rappahannock River into the Shenandoah Valley, and Hooker’s army, in cautious pursuit, was having a difficult time locating them. At Brandy Station on June 9, Confederate cavalry roughly handled their Federal counterparts after a seesaw battle. The cavalrymen then drove to within 10 miles of Washington, sending panic through the capital.

On June 15, the lead elements of Lee’s army crossed the Potomac into Maryland, and on June 22 they crossed the Mason-Dixon Line into Pennsylvan...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- TOURING THE BATTLEFIELD

- FOREWORD by Mark H. Dunkelman

- PROLOGUE: The First Battle of Gettysburg

- CHAPTER ONE: The Campaign

- CHAPTER TWO: First Shots

- CHAPTER THREE: Fight Like the Devil

- CHAPTER FOUR: Herbst Woods

- CHAPTER FIVE: The Death of John Reynolds

- CHAPTER SIX: The Railroad Cut

- CHAPTER SEVEN: Oak Hill

- CHAPTER EIGHT: Oak Ridge

- CHAPTER NINE: The XI Corps Arrives

- CHAPTER TEN: Collapse

- CHAPTER ELEVEN: Battle in the Brickyard

- CHAPTER TWELVE: The Key to the Battlefield

- CHAPTER THIRTEEN: Cemetery Hill

- EPILOGUE

- APPENDix A: Where Was Jeb Stuart? by Eric J. Wittenberg

- APPENDix B: Shoes or No Shoes? by Matt Atkinson

- APPENDix C: The Most Second-Guessed Decision of the War by Chris Mackowski and Kristopher D. White

- APPENDix D: Reynolds Reconsidered by Kristopher D. White

- APPENDix E: The Harvest of Death by John F. Cummings III

- APPENDix F: Amos Humiston and the Children of the Battlefield by Meg Thompson

- APPENDix G: Pipe Creek by Ryan Quint

- APPENDix H: The Peace Light Memorial by Dan Welch

- ORDER OF BATTLE

- SUGGESTED READING

- ABOUT THE AUTHORS