eBook - ePub

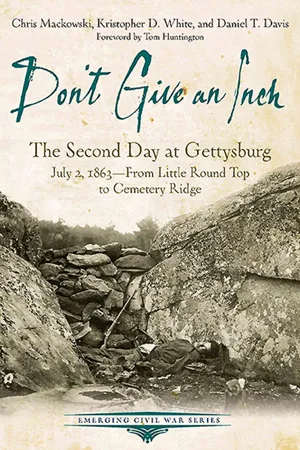

Don't Give an Inch

The Second Day at Gettysburg, July 2, 1863—From Little Round Top to Cemetery Ridge

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Don't Give an Inch

The Second Day at Gettysburg, July 2, 1863—From Little Round Top to Cemetery Ridge

About this book

This vividly detailed Civil War history reveals many of the incredible true stories behind the legendary sites of the Gettysburg battlefield.

Having unexpectedly been thrust into command of the Army of the Potomac only three days earlier, General George Gordon Meade was caught by a much harsher surprise when the Confederate Army of North Virginia launched a bold invasion northward. Outside the small college town of Gettysburg, the lead elements of Meade's army were suddenly under attack. By nightfall, they were forced to take a lodgment on high ground south of town. There, they fortified—and waited. "Don't give an inch, boys!" one Federal commander told his men.

The next day, July 2, 1863, would be one of the Civil War's bloodiest. With names that have become legendary—Little Round Top, Devil's Den, the Peach Orchard, the Wheatfield, Culp's Hill—the second day at Gettysburg encompasses some of the best-known engagements of the Civil War. Yet those same stories have also become shrouded in mythology and misunderstanding. In Don't Give an Inch, Emerging Civil War historians Chris Mackowski and Daniel T. Davis peel back the layers to share the real and often-overlooked stories of that fateful summer day.

Having unexpectedly been thrust into command of the Army of the Potomac only three days earlier, General George Gordon Meade was caught by a much harsher surprise when the Confederate Army of North Virginia launched a bold invasion northward. Outside the small college town of Gettysburg, the lead elements of Meade's army were suddenly under attack. By nightfall, they were forced to take a lodgment on high ground south of town. There, they fortified—and waited. "Don't give an inch, boys!" one Federal commander told his men.

The next day, July 2, 1863, would be one of the Civil War's bloodiest. With names that have become legendary—Little Round Top, Devil's Den, the Peach Orchard, the Wheatfield, Culp's Hill—the second day at Gettysburg encompasses some of the best-known engagements of the Civil War. Yet those same stories have also become shrouded in mythology and misunderstanding. In Don't Give an Inch, Emerging Civil War historians Chris Mackowski and Daniel T. Davis peel back the layers to share the real and often-overlooked stories of that fateful summer day.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Don't Give an Inch by Daniel T. Davis,Chris Mackowski,Kristopher D. White in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Histoire & Histoire de la guerre de Sécession. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Before July 2

CHAPTER ONE

JUNE 26-JULY 1, 1863

Dawn of July 2, 1863, revealed something to the citizens of Gettysburg they must never have imagined: Confederates occupied the high ground to the north, east, and west of the small college town.

Rebels had rolled through the town once already, on June 26, plundering the town’s stores and forcing many residents to flee. Then, on the morning of July 1, the entire Confederate Army of Northern Virginia materialized on the town’s western and northern edges.

The Federal Army of the Potomac had begun gravitating toward the town, too, but not in large enough numbers to keep the Confederates at bay. By mid-afternoon, Federal soldiers trying to resist the Confederate onslaught found themselves tumbling pell-mell through the town, where they rallied on the heights of Cemetery Hill.

The village now found itself situated squarely—uncomfortably—between the lines of the two opposing armies. “The beautiful dawn of the second day of the battle,” recalled one Federal, “looked upon the bulk of both great armies in readiness for action….”

* * *

The first day of the battle of Gettysburg had been a resounding, if not sloppy, Confederate victory. Lee’s army had smashed two Federal infantry corps and inflicted some 9,000 casualties, compared to only 7,000 suffered.

Lee had moved north beginning on June 3, eyeing Pennsylvania as a target because of the political turmoil his presence there would cause while threatening the cities of Baltimore, Harrisburg, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C. He also hoped the move would alleviate the Federal stranglehold around Vicksburg, Mississippi, by forcing Lincoln’s War Department to shift troops from there to the east to meet the aggressive Confederate threat stabbing its way north of the Mason-Dixon line. Finally, Lee hoped his army would enjoy the bounty of Northern farms, storehouses, cellars, and larders, which had thus far been untouched by the hard hand of war, unlike the depleted region of central Virginia, which had been stripped nearly bare.

OPPOSING FORCES—The first day of battle, to the north and west of Gettysburg, resulted in a rout of Federal forces, which then rallied on Cemetery Hill south of the town and hunkered down in a U-shaped formation to face the Confederates arrayed against them. The Federal right flank anchored on Culp’s Hill; the left stretched down toward Little Round Top, with the addition of cavalry protection from Brig. Gen. John Buford’s division. III Corps commander Maj. Gen. Dan Sickles advanced a portion of his force to the Emmitsburg Road in support of the cavalry. Buford received orders to move to the Federal rear to protect the supply line; after he left, Sickles moved his entire corps forward against orders to high ground around the Peach Orchard. Confederates, meanwhile, looked to shift southward around the Federal flank, unsure of its exact position even before Sickles began his movement.

The Army of Northern Virginia did enjoy a bountiful march into Pennsylvania, winning a small string of minor engagements along the way. They did not, however, encounter droves of Federals quickly shuffled eastward from Mississippi to meet them. In fact, the only real change in Northern forces occurred at the head of the Army of the Potomac: on June 28, Lincoln replaced Maj. Gen. Joseph “Fighting Joe” Hooker with Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade. Lincoln also placed the garrisons of Washington and Harpers Ferry at Meade’s disposal—formerly a bone of contention with Hooker.

Hooker already had the army in pursuit of Lee, and when Meade took over, he immediately assessed his options. The army was fanned out over a twenty-mile arc, with cavalry patrols out even farther. Considering a strong defensive position near Pipe Creek along the Pennsylvania-Maryland border, Meade hoped to consolidate his forces there and entice Lee to attack him. However, word soon arrived from Gettysburg that the lead elements of the army had stumbled into contact with Confederates. As the situation devolved into a crisis, Meade began to shift his entire army in that direction.

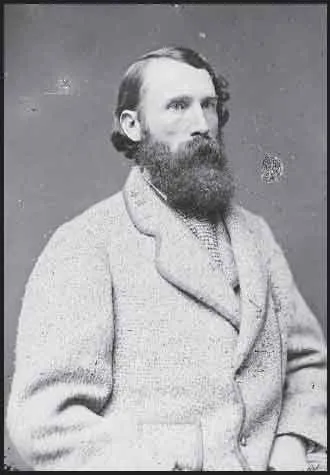

A native Pennsylvanian, West Point graduate, and antebellum engineer, Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade had fought in many of the Army of the Potomac’s earlier battles, steadily rising from brigade to corps command. Lincoln appointed Meade to army commander on June 28 even though he was junior in rank to subordinates Henry Slocum, John Sedgwick, and John Reynolds, who all demurred opportunities for promotion. A proven soldier, Meade now faced a crisis in his home state. (loc)

Trusted subordinate Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock, sent to assess the situation on Meade’s behalf, arrived late in the afternoon to find the remnants of Federal forces consolidating on Cemetery Hill. Hancock sent approving word to Meade that they occupied “the strongest position by nature upon which to fight a battle that I ever saw.”

Thus, the battlefield John Buford recognized, John Reynolds chose, and Winfield Scott Hancock confirmed—Gettysburg—would serve as the Army of the Potomac’s next great battlefield.

With the XI Corps holding Cemetery Hill, the XII Corps positioned itself on the army’s right to hold Culp’s Hill. Battered units from the I Corps, struggling to reassemble after being crushed during the July 1 fight, joined them. To the left of the XI Corps, Hancock’s II Corps filed in along a ridge that ran southward—the aptly named Cemetery Ridge. Beyond, the arriving III Corps would make up the army’s left flank, linking with the II Corps and anchoring on a prominence known as Little Round Top.

By midday or so on July 2, Meade also expected his old V Corps on the field, which could bolster the line where needed. The army’s largest corps, the stalwart VI Corps, would bring up the rear and serve as a reserve. “Tell General Sedgwick,” wrote Meade to the VI Corps commander, “that I … hope he will be up in time to decide victory for us.”

In total, Meade would have more than 84,000 troops to call on, taking into account his losses on the first day. Lee, in contrast—though Meade did not precisely know it—would have 64,000 troops still available to fight.

“Then began one of the hardest marches we ever knew—thirty six miles in dust and unusual heat,” a VI Corps soldier remembered; but the men pressed on with vigor and courage through it all, feeling themselves on Northern soil again and feeling that we were expected to decide the victory.”

A monument marking the spot where Union Maj. Gen. John Reynolds fell is one of the most-visited spots on the July 1 battlefield. While there’s no way to tell the impact Reynolds might have had on the battle of Gettysburg, his martyrdom there on the first day of battle has inflated him into the stuff of legend. It is fair to say that Meade trusted his friend Reynolds implicitly and had leaned on him heavily during Meade’s first few days as commander of the Army of the Potomac. (cm)

* * *

As early as 5:00 p.m. on the afternoon of July 1—as Cemetery Hill swarmed with more and more Federals—Robert E. Lee and James Longstreet began debating their next move. Through field glasses, Longstreet observed the formidable Union position from afar. The specter of what lay ahead did not entice him.

The enemy occupied the commanding heights of the city cemetery, from which point, in irregular grade, the ridge slopes southward two miles and a half to a bold out cropping height of three hundred feet called Little Round Top, and farther south half a mile ends in the greater elevation called [Big] Round Top. The former is covered from base to top by formidable boulders…. At the Cemetery his line turned to the northeast and east and southeast in an elliptical curve, with his right on Culp’s Hill.

Rather than attack the fortified Federal position, which sat atop ground favorable to the defenders, Longstreet suggested that the army disengage and swing southward. “All that we have to do is file around his left flank and secure good ground between him and his capital,” the Old War Horse pointed out.

By the end of July 1, the Union army had rallied atop Cemetery Hill at a position chosen by XI Corps commander Maj. Gen. Oliver Otis Howard, whose statue still overlooks the ground today. (cm)

If Lee gave up the fight on the evening of July 1 as Longstreet suggested, the battle of Gettysburg would have been a minor engagement scored as a minor Confederate victory. However, having failed to finish off the Federals during the two previous battles—Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville—Lee opted to try this time for the killing stroke.

And so it was, during the early morning hours of July 2, much of the Southern high command reconnoitered the enemy lines. Confederate cavalry chief Maj. Gen. James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart was still away from the main army with three brigades, meaning that Lee did not have his most reliable intelligence officer on hand. Nor was Lee effectively utilizing the cavalry that had remained with the army. Thus, Lee relied heavily on his own eyes and staff officers to scout the main Federal lines.

Not only did Lee need to find a weak point in the Federal lines, he also needed to come up with the proper units within his own army to use as his strike force. Both seemed difficult to locate.

The July 1 battle had battered three of the four Confederate divisions engaged. Lieutenant General A.P. Hill’s Third Corps had been ill led and roughly handled. Those losses and the general location of the corps on northern Seminary Ridge at the heart of the main Confederate battle line left the Third Corps in no position to spearhead an attack. However, it could support an assault to the east or south of the town.

Lieutenant General Richard S. Ewell’s Second Corps, meanwhile, was in a position to make an assault. While two of his three divisions fought on July 1, only one had sustained heavy casualties, meaning at least two-thirds of the Confederate Second Corps was fresh and could conceivably spearhead the day’s offensive.

Lee met with Ewell and two of his strong-willed division heads—Maj. Gen. Jubal Early and Maj. Gen. Edward “Allegheny” Johnson—on the night of July 1. All three subordinates opposed assaulting the Federal lines on their front. The rugged nature of the ground, the heavily wooded eminences of Wolf and Culp’s hills, and the stoutly defended Cemetery Hill would all hamper offensive operations in their sector, they argued.

With Hill unble to lead an assault, and Ewell dead set against a frontal attack, only one viable option remained to Lee: Longstreet’s First Corps, which he could launch against the Federal left flank.

Lt. Gen. Ambrose Powell “A.P.” Hill had led the famed Light Division under “Stonewall” Jackson in 1862 and early 1863. Although Hill did not get along with Jackson, Lee chose him to command the newly created Third Corps, formed after Jackson’s ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Maps

- Acknowledgments

- Touring the Battlefield

- Foreword

- Prologue: The Old Gray Fox vs. The Old War Horse

- Chapter One: Before July 2

- Chapter Two: Pitzer’s Woods

- Chapter Three: Longstreet’s March

- Chapter Four: Hood Attacks

- Chapter Five: The Assault Against Little Round Top

- Chapter Six: The Defense of the 20th Maine

- Chapter Seven: Devil’s Den

- Chapter Eight: The Wheatfield

- Chapter Nine: The Peach Orchard

- Chapter Ten: The Wounding of Dan Sickles

- Chapter Eleven: Cemetery Ridge

- Epilogue

- Appendix A: The Wheatfield: A Walking Tour

- Appendix B: The Hero of Little Round Top?

- Appendix C: Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter

- Appendix D: Not a Leg to Stand On: Sickles vs. Meade in the Wake of Gettysburg

- Order of Battle

- Suggested Reading

- About the Authors