eBook - ePub

Another Bloody Chapter in an Endless Civil War

Northern Ireland and the Troubles, 1984–87

- 376 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Another Bloody Chapter in an Endless Civil War

Northern Ireland and the Troubles, 1984–87

About this book

Four years of bloodshed in mid-1980s Northern Ireland, in the words of British soldiers who experienced it firsthand. Includes photos.

Proceeding month-by-month from 1984 through 1987, this historical project provides a deep and detailed portrait of the British military experience in a period of frequent and unpredictable violence as the Provisional IRA grew in financial and logistical strength. As British Security Forces worked to contain the chaos, the Republican terror group fully embraced Danny Morrison's mantra— "The Armalite and the ballot box"—as they moved toward a realization that the British military could not be beaten, but that they could at least sit down with them from a position of strength.

The goal was to keep up the pressure and force the British government to the bargaining table. But as the Provisionals and Loyalists fought, talked, and then fought again, a further 356 people died. Through oral histories, witness accounts, photos, and commentary, this book covers every major incident of the period, from the ambush of off-duty UDR soldier Robert Elliott to the bombing of Enniskillen. It also looks at the continued interference of the United States and the vast contribution of its citizens through NORAID, which ensured the killing and violence would continue. Lamenting brutality and the targeting of innocents regardless of the perpetrator's sympathies, veteran Ken Wharton, who has chronicled the Troubles extensively, reminds us of the universal threat, and horrifying toll, of terrorist tactics.

Proceeding month-by-month from 1984 through 1987, this historical project provides a deep and detailed portrait of the British military experience in a period of frequent and unpredictable violence as the Provisional IRA grew in financial and logistical strength. As British Security Forces worked to contain the chaos, the Republican terror group fully embraced Danny Morrison's mantra— "The Armalite and the ballot box"—as they moved toward a realization that the British military could not be beaten, but that they could at least sit down with them from a position of strength.

The goal was to keep up the pressure and force the British government to the bargaining table. But as the Provisionals and Loyalists fought, talked, and then fought again, a further 356 people died. Through oral histories, witness accounts, photos, and commentary, this book covers every major incident of the period, from the ambush of off-duty UDR soldier Robert Elliott to the bombing of Enniskillen. It also looks at the continued interference of the United States and the vast contribution of its citizens through NORAID, which ensured the killing and violence would continue. Lamenting brutality and the targeting of innocents regardless of the perpetrator's sympathies, veteran Ken Wharton, who has chronicled the Troubles extensively, reminds us of the universal threat, and horrifying toll, of terrorist tactics.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Another Bloody Chapter in an Endless Civil War by Ken Wharton in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9781912174270Subtopic

Irish HistoryPart One

1984

During this year, the first under review, a total of 34 soldiers or former soldiers died in, or as a consequence of the troubles. A total of 15 were from mainland Regiments and 18 were UDR or former UDR members killed because of their past association with the Regiment. Additionally, 35 of the dead were civilians and nine policemen died. A total of 81 people died in this 12 months; it was one of the lowest years for fatalities by this period of the troubles. It was also a year in which the De Vere Grand Hotel in Brighton was suddenly front-page news. It was the year in which Gerry Adams was shot.

1

January

The first month of the New Year witnessed nine deaths; four soldiers, all from the UDR were killed as were three police officers and two civilians. It was also the month when the ‘white-washing’ over the 1983 Maze ‘Great Escape’ became public knowledge, as officialdom managed to dodge responsibility for its incompetence.

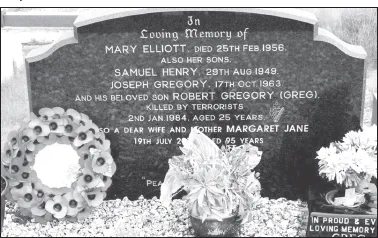

The New Year had barely ushered out the old, when the Provisional IRA killed an off-duty UDR soldier. Private Robert ‘Greg’ Elliott (25) lived in Castlederg, Co Tyrone, very close to the Irish border, and whilst, strictly speaking, anywhere was dangerous for off-duty members of the regiment to live, the proximity of the border exacerbated the danger. He lived with his widowed mother in Lislaird Road in Mournebeg, just outside the largely Nationalist Castlederg; he was an easy target and PIRA killers had done their homework. On the evening of the 2nd, he received a phone call, thinking that it was from a friend who wanted him to do a job for him. But, as he went outside, armed men who had lain in wait for him to exit the house, jumped over his garden wall; they poured at least 14 shots at him, hitting him in the head and chest. He died almost instantly and was probably already dead when his mother, alerted by the gunshots ran outside to his vehicle. Greg’s brother who lived on a farm close by, also heard the shooting and made his way to the house but was unable to help. One of those involved was Declan Casey; a PIRA gunman who later turned informer. The killers ran across fields to a car which was waiting for them in nearby Lisnacloon Road; from there it was a short drive to Carn Road, and then across the nearby border where the Gardaí Siochana could be relied upon to turn a blind eye.

Grave of UDR soldier, Robert Gregg, killed whilst off-duty by the IRA 2/1/1984: at Castlederg Cemetery.

Scene of the murder of UDR soldier Greg Elliott by the IRA in 1984.

WHAT NI DID TO ME

Stuart Martin, Royal Corps of Transport

I was an RCT driver attached to another unit based at New Barnsley RUC station and Kids’ school, at the top end of the ‘Murph in West Belfast. We were forever plagued with Paddies coming to the gates drunk and hurling abuse and other stuff at us. Anyway, one particular night, we had this really abusive guy who just would not go away or shut up, so the officer in charge told us to grab him and take him away. This we did, and we slung him into the back of my PIG and took him and dropped him in a Protestant area, and told some kids in the street to sort it. I am pleased to say, that they did; if you get my drift? He was found the next day in a very sorry state!

Also, we had one particularly unpleasant dog which used to wait by the base entrance, whether by instinct or trained to do so, and bark in a really vicious way at us. [Many and one does mean: many, dog owners trained their dogs to attack soldiers when they came into their area on foot patrols.] One day coming back into camp from a patrol in my PIG, there was the aforementioned dog who barked every time that soldiers left on foot patrol; it looked savage! Now I am a dog-lover, but I had had it with the dog, the insults, the abuse, the hurled rocks and all, so I drove over it! I had a big mess to clean up on my vehicle and the dog was still howling in pain when the gates closed. I am not that type of person normally and I am not proud of what happened, but this just shows how inhuman we can be in certain situations.

One of our lads whom I shall just call Steve ‘H’ had a favourite pastime; this was to go out on night patrol in his Saracen and see how many cars he could demolish! Naturally because it was dark, no-one was able to report him! One day, some ‘Murph kids from near the Pope Pious Church, inside the estate threw stones at his vehicle and he chased them through the church ripping down the gates, and causing all sorts of damage! That was one complaint that he couldn’t avoid and he was torn off a strip for that one! One night I was on the roof sangar looking over the estate and we saw the OC running out in his all-black tracksuit. We just thought: what a fucking idiot! About twenty minutes later he was seen returning to the base, only running a lot faster than he left. Then, a few minutes later, we saw black smoke coming from the centre of the ‘Murph and we phoned in to alert the fire people. We were told to keep our eye on the local trouble spot, which the local thugs used, and report in only when we could actually see flames! The OC wanted to make sure that the Community Centre – which he just set fire to – would burn down properly!

A little over a week after the murder of the UDR soldier, and with his coffin barely in the ground of Castlederg’s New Cemetery, IRA gunmen were again killing off-duty members of the SF. RUCR Constable William Fullerton (48) had just finished duty at the RUC station in Warrenpoint, Co Down. As he drove past an Industrial Estate on Warrenpoint Road, Newry, waiting gunmen in a stolen Ford Cortina opened fire with automatic weapons. The policeman was hit at least five times and dreadfully injured. He was rushed to hospital in Banbridge where he died shortly afterwards. The estate is close to Sheeptown and is approximately seven miles from the scene of the Warrenpoint massacre, which resulted in the deaths of 18 soldiers in August 1979. [The incident is dealt with in the author’s Wasted Years, Wasted Lives; Vol 2 by Helion & Company]. Like the killers of Private Elliott eight days earlier, the killers had a short run to the safety and terrorist sanctuary of Ireland. With the Nationalist Derrybeg Estate also within easy reach, they had no shortage of willing helpers and ‘safe houses.’

Between 1945 and 1996, a total of eight Australian Federal Police officers were killed in the course of duty on the Australian mainland and Tasmania. In New South Wales (population 7.6 million) in the period 1969–97 (parameter years for the Northern Ireland troubles), a total of 30 officers were killed in the course of duty. Similarly, in Queensland, with a population of 4.8 million, there were 28 deaths. Causes of death were gunshot wounds, stabbings, RTAs during pursuit and deaths at VCPs.

During the years in which this author has lived in Australia (2009–2015) there have been seven deaths amongst the police of the seven Australian states. The years 1969–97 saw the deaths of 306 officers in Northern Ireland alone, with its then population of 1.5 million. For the two aforementioned Australia states to have witnessed the same – per capita – rate of death, there would have been 2,530 police officers killed. This puts the staggering number of police deaths in a tiny island, such as Ulster, with its relatively tiny population into a real and horrifying perspective.

On the 14th, it was heartening to see that, amidst the violence and death of the troubles, places like Co Fermanagh could still report ‘normal news’ also. During the research for this book, the author found the following: ‘On being cautioned for not wearing a seatbelt, a Garrison housewife, Mrs Rose Anne Keown, Drumnascreane, ‘blew raspberries’ at police. She was fined £35 and her husband Charles Joseph Keown (65), was fined £15 for using a car with defective parts and accessories. Neither defendant was legally represented nor made a court appearance.’

On Sunday 15th, Catholic Primate of Ireland, Tomás Ó Fiaich, sparked controversy when he criticised the visit of Margaret Thatcher to Northern Ireland. She had purposely and very publically demonstrated her support for the under fire UDR, by visiting their base in Armagh. Ó Fiaich described the visit as ‘disgusting’ and then exacerbated his outrageous and provocative remarks when he stated that people would be morally justified in joining Sinn Féin. Even the vacillating and Republican-appeasing Irish government distanced itself from the Cardinal’s remarks.

The Kincora Boy’s Home scandal has been dealt with in previous books by the author and there is no intention to re-open this issue in any great detail in this works. However, it was back in the News on the 18th, when Northern Ireland Secretary James Prior, announced a public inquiry into the scandal. Readers may be aware that the home in Belfast had seen paedophile activity on a large scale, allegedly, involving senior members of the staff there. William McGrath, Raymond Semple and Joseph Mains, were charged with a number of offences relating to the systematic sexual abuse of children in their care over a number of years. There were allegations that McGrath was an informant for MI5 and that the activities were covered up by both the RUC and the Government.

Two days later, another off-duty UDR soldier was shot, and killed in his own home, as three more members of the Regiment died in a 48 hour period. Private Linden Houston (30) was a full-time soldier in the regiment and lived in the predominantly Loyalist Dunmurry area of South Belfast. Sunnymede Avenue is just south of Golf Club and is a well-to-do area; however, just a few hundred metres away, is the periphery of the Nationalist Twinbook from where his INLA killers came. Where Private Houston lived is not on a well-travelled route and the killers must have followed him home on a number of occasions, in order to work out their journey from the Twinbook Estate. During the evening of the 20th, under cover of darkness, masked INLA gunmen knocked at the soldier’s front door, and shot him as he appeared in the doorway. He was hit in the upper chest and neck and though mortally wounded, he somehow managed to crawl back into the house where he collapsed and died in his wife’s arms. One of his killers was caught soon afterwards and sentenced to life imprisonment, some five months after the murder.

The author interviewed ‘Rob’ whose stories, although outside this book’s parameters, nevertheless contain a relevance which is germane to the period. He is a former soldier in The Duke of Wellington’s; affectionately known as the ‘Duke of Boots.’ His story follows:

‘Rob’ Duke of Wellington’s

It’s the same old shit isn’t it? Anything that embarrasses the Army is quietly swept under the carpet. You know the mind-set back then: there can be no sign of weakness. If you had a problem, you kept it to yourself and soldiered on. The closest thing you had was a little chat with the padre, and even then there was no guarantee he wouldn’t say something to your section or platoon commander. When I look back on those days I sometimes wonder how any of us came out of it without losing our minds. I was 18 years old when I served in Northern Ireland and it almost broke me; I am 43 years old now and I still feel the effects of it.

I remember the rain, the dark streets and abandoned buildings. I remember the long patrols with little sleep, carrying that white sifter as tail end Charlie. I remember the grotty little rooms with four men squeezed in a space only meant for two. I remember the riots and the burning cars and busses lighting up the sky, as we were sent in to be bricked and bottled on the shield line. I remember seeing a young lad with half his leg missing on the Stewartstown road and feeling helpless and angry that I couldn’t do anything. I remember having to go into the waste ground where they had planted a device against the fence in the dark. We had just one torch between four men, and I was thinking that my next step would be my last, as I waited for the secondary to go off; thankfully the boyos didn’t plant one that time.

As for the unknown deaths I have told you all I know, but if I remember anything else I will let you know. Ken I was almost one of the unrecorded names on that list, I thought of putting my rifle under my chin and pulling the trigger and to be honest, there have been times over the years when I wished I had. I am just now coming to terms with it and hopefully the people at Combat Stress can carry me that last few yards.

I keep coming back to the list of our dead: WOII Peter Lindsay – unknown; Private Louis Carroll – unknown; Private John Connor – unknown; Private Jason Cost – unknown. Why so many unknown causes of death? Is this typical? How the hell can we not know how and why they died? Is the Army’s record keeping so lax that they didn’t record why they died? Or like John, are their deaths ones that the Army didn’t want to record? It’s not right that the reason of their passing is not recorded. Were their deaths even recorded on the Roll of Honour for Northern Ireland?

Thanks to the good offices of Michael Sangster and Mark ‘C’, I can now add the following: John Connor died in an RTA, Louis Carroll in an accident and Jason Cost in an accidental firearm incident.

On the 22nd, two more soldiers died, not as a result of terrorist action – as the MOD like to label it, in order to artificially deflate the casualty figures – but as a consequence of being involved in the troubles. Private Norman Frazer Brown (37) died in an RTA, whilst on duty in Co Fermanagh. His funeral was held in Rossery Cemetery in Enniskillen. On the same day, Private William James McShane (19) died in circumstances, under which this author is only permitted to describe as ‘….violent or unnatural causes….’ He was killed in the Dungivern area of Co Londonderry; regrettably, nothing further is known.

ACCIDENT OR NOT?

Gary Austin, Light Infantry

I have looked at the different statistics of fatalities; I say ‘different’ because no one seems to know shit about the actual true numbers. In one stat, I read that around 200 died from RTA and other accidents, and I came across just one admission of one soldier being killed in a Land Rover by hostile action; basically being hit in the head by a missile – a brick. Ken, I believe these figures to be total bullshit by the MOD.

On my tour during the 80s, I experienced this twice myself. The first time was when I was on a foot patrol down Obins Street in Portadown: an industrial brick was thrown over an old disused factory wall, which I was walking along and landed four to five feet away, but right in front of my path. The thrower got my position correct but timed it wrong, thankfully. The brick was heavy duty and didn’t even break. However, had that bastard delayed throwing it by two seconds or so, it would have killed me outright; no question about that as I was wearing a beret!

The second incident happened one night whilst on a mobile patrol. We were travelling back to base and I was travelling in the lead landie, somewhere on the outskirts of Lurgan. At the time we were possibly doing 40 mph and I was sat in the back, behind the driver’s side of a canvass-clad vehicle which had no doors on; you get the picture? It had been quiet without incident and that was it – we were going home so to speak. You know how it was; we were tired, there was no talking and we were just listening to the distinct drone of the vehicle. Suddenly: wallop; several missiles peppered the vehicle and a loud scream came from the officer in the front passenger side. I instantly cocked my weapon but couldn’t do anything because of another landie following behind; in any case, I couldn’t see anyone as there was banking either side of the road, and as I said, it was dark. They were not hit and we just carried on. It was over as fast as it started and I didn’t have time to feel any fear. The officer was in a lot of pain; he’d been hit in his left elbow and looked in a bad way. He ended up in a sling, but luckily had no breaks and was on light duties for around four weeks.

My point here is this; a foot higher and it would have killed him stone dead! Also, had it hit our driver, then no doubt our vehicle would have left the road and plummeted down the banking; that possibly would have been the four of us done for. ‘Accident not hostile action’ would most likely have been the report. Also, had I copped it on that foot patrol, what would that have been put down to; hostile action or accident? I’m not so sure now!

Lastly, I also did guard duty at Musgrove Park Hospital and there was a soldier in intensive care due to an RTA. He died and I remember seeing his mum crying, who had been flown over by the Army. When I think back to my own experiences, I do wonder if his death was a true RTA or hostile action. I understand there will be accidents of course, but I don’t believe, for one minute, the stats on this. The amount of violence, with bricks, kitchen sinks or whatever else that was thrown at us, must have caused many deaths, but to hide the true casualty figures just to keep the statistics down, is an injustice to all, in my opinion.

Londonderry is known as ‘stroke city,’ not because of an increased incidence in cerebral vascular events amongst those with high blood pressure, but because it was known as Londonderry/Derry. To the Loyalists and to the British, it is the former and to the Irish and Nationalists, it is Derry. On the 24th, Londonderry District Council was given permission by the Northern Ireland Office (NIO) to change the name of the council to Derry District Council. The official name of the city remained Londonderry, but most Loyalists were left seething with an impotent rage. Then, in an incident which echoes a most inappropriate decision some 30 years later in Belfast, Derry District Council also voted to stop flying the Union Flag on council property.

On the 26th, the Hennessy Report, into the ‘The Great Escape’ of 38 convicted PIRA/ INLA terrorists from the Maze the previous September, was made public. In its preface, James Prior wrote: ‘I arrived in Belfast on the morning of Monday 26 September 1983, the day following the escape of 38 prisoners from HM Prison, Maze. At our meeting at Stormont that day you asked me to conduct an Inquiry into the security arrangements at the Maze. You asked me to interpret my brief as widely as possible and to look at all aspects of security. I began work that afternoon.’ Prior continued: ‘We interviewed the Governor and those members of his staff, who had been on duty on 25 September or whose duties touched upon aspects of security in which we were interested, or who asked to see us in response to the letter we sent to every member of staff at the Maze. We contacted, or were contacted by, staff who had served at the prison in the past. We made clear to witnesses that their statements would not be shown to persons outside the Inquiry (unless required by a court) and would not be used against them in disciplinary proceedings. In total, we interviewed 115 past or present members of staff, while six submitted written evidence. We also wrote to each prisoner offering him the opportunity to submit written evidence, again making clear that any statements made to us, would be regarded as confidential. Twenty-eight inmates gave written evidence. We also talked to all inmates involved in the escape who were back in prison custody. We had discussions with the Secretary of State on two occasions and also with the Minister of State responsible for prisons. We saw the Permanent Under-Secretary of State at the Northern Ireland Office and members of his staff. We saw the General Officer Co...

Table of contents

- Cover

- About the author

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedications

- Contents

- List of Maps and Illustrations

- Foreword by Damien Lewis

- Preface by Tim Francis

- From the Author

- Comment from a Former Soldier

- Note to the Reader

- Introduction

- Preamble

- Part One: 1984

- Part Two: 1985

- Part Three: 1986

- Part Four: 1987

- Notes

- Epilogue

- Appendices

- Select Bibliography