![]()

Chapter 1

A Vast Sea of Misery: The Wagon Train of Wounded

“As many of our poor wounded as possible must be taken home.”

— Robert E. Lee

THREE DAYS OF COMBAT AT Gettysburg decimated Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Confederate losses were at least 4,637 killed, 12,391 wounded and 5,161 missing.1 The enormous task of safely evacuating the ambulatory from the field fell upon Brig. Gen. John D. Imboden. Fortunately for the Confederates, Imboden rose to the occasion and turned in his finest performance of the war during the ordeal that followed.

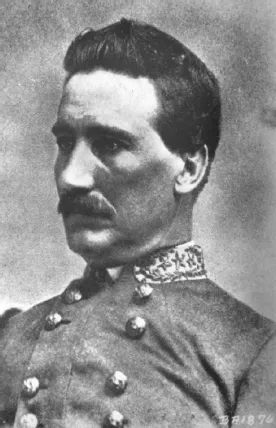

John Daniel Imboden was born forty years earlier near Staunton, Virginia. He attended, but did not graduate from, Washington College in Lexington (today Washington & Lee University). Imboden taught for a time at the Virginia Institute for the Education of the Deaf, Dumb, and Blind in Staunton, studied law, practiced in Staunton, and was twice elected as a representative to the Virginia Legislature.2 He won acclaim as the commander of the Staunton Artillery at Harpers Ferry, and was wounded at First Manassas in July 1861. The following year, Imboden resigned from the artillery to raise companies of partisan rangers. He fought at Cross Keys and Port Republic during Stonewall Jackson’s Valley Campaign.

In January 1863, Imboden received a promotion to brigadier general. His 1st Virginia Partisan Rangers reorganized into two regular cavalry regiments, the 18th Virginia Cavalry and the 62nd Virginia Mounted Infantry, and a battery of horse artillery. However, Maj. Gen. James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart, the Army of Northern Virginia’s cavalry division chief, was not fond of Imboden, so his command was not made part of the “regular” mounted forces of the army.

Because of Stuart’s animus, Imboden’s independent Northwestern Brigade received orders directly from General Lee. Imboden and Brig. Gen. William E. “Grumble” Jones led what came to be known as the “Jones- Imboden Raid,” a mounted strike into northwestern Virginia during April and May 1863. The raid captured thousands of horses and cattle for the Confederacy and severed the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad.3 During the Gettysburg campaign, Imboden’s command included the 18th Virginia Cavalry, led by his brother Col. George H. Imboden; the 62nd Virginia Mounted Infantry under Col. George H. Smith; the Virginia Partisan Rangers under Capt. John H. “Hanse” McNeill; and the Staunton Horse Artillery, Virginia Battery, under Capt. James H. McClanahan—in all, some 2,245 troopers.4

![]()

Brig. Gen. John D. Imboden, Commander, Northwestern Brigade.

USAHEC

![]()

Once it became apparent the battle of Gettysburg had ended, Imboden was summoned to army headquarters at 1:00 a.m. on July 4. A weary General Lee arrived, dismounted, and leaned against his horse, Imboden recalled, “The moon shone full upon his massive features and revealed an expression of sadness that I had never before seen upon his face. Awed by his appearance, I waited for him to speak until the silence became embarrassing.”5 Imboden broke the silence. “General,” he exclaimed, “this has been a hard day on you.”

“Yes, it has been a sad, sad day to us,” replied Lee. He praised the performance of Pickett’s Virginians during the infantry assault of the previous day, and then added mournfully, “Too bad! Too bad! Oh! Too bad!”6

Lee’s headquarters tent and those of his staff were staked among the fruit trees of an orchard on the south side of the Chambersburg pike west of Seminary Ridge.7 Lee motioned Imboden into his tent, where the tired commander seated himself and explained the situation. “We must now return to Virginia,” observed Lee. “As many of our poor wounded as possible must be taken home.” Lee continued:

The next morning, a staff officer delivered Imboden’s written orders and a large envelope addressed to Davis.10 The success of the route of retreat would hinge upon speedy movement and security for the wagon train. Lee impressed upon Imboden that “there should be no halt [along the way] for any cause whatever.” Lee’s staff prepared a detailed evacuation plan and provided Imboden with specific direction:

With his orders in place, Imboden set about preparing for the heavy task that lay ahead of him.

![]()

![]()

Assembling the Wagon Train

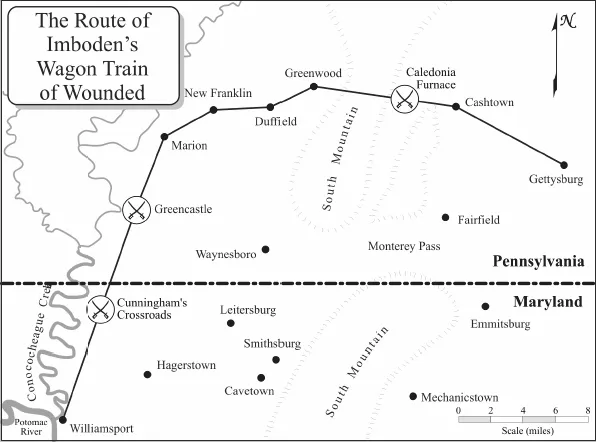

The shortest route to Hagerstown, Maryland, was via Fairfield and the Monterey Pass above it. Unfortunately for Imboden and his already sizeable task, the Monterey Pass was steep, very narrow, and the road wound in a series of sharp turns. Lee knew that Union soldiers were operating in the area. If the enemy cavalry choked off this route, the consequences for the withdrawal would be devastating. Therefore, Lee decided to send the main army by the Fairfield route.

Imboden’s wagon train would have to take a cross-country route. It would move west along the Chambersburg Pike through the Cashtown Pass, turn south at Greenwood and proceed on to Marion, pass south through Greencastle and into Williamsport. This route was less likely to be blocked or otherwise impeded, but it too was fraught with peril. The trip would be longer, and there would be more opportunities for Union soldiers to play havoc with the long column.

Confederate preparations for the retreat did not go unnoticed by the town’s citizens. On edge after three interminably long days, even the slightest movement grabbed attention. Teenager Daniel A. Skelly and his family had been caught squarely in the middle of the “exciting” scenes in town over the course of the battle. As an old man, Skelly reflected on the night of July 3. He had tried to go to sleep in his West Middle Street home, but was “restless, and was unable to sleep soundly. About midnight I was awakened by a commotion down in the street,” he recalled. “Getting up I went to the window and saw Confederate officers passing through the lines of the Confederate soldiers bivouacked on the pavement below, telling them to get up quietly and fall back. Very soon the whole line disappeared.” As Skelly remembered it, “we had to remain quietly in our homes for we did not know what it meant. I went back to bed but was unable to sleep.12

The task of assembling hundreds of wagons and ambulances and carefully loading the wounded began in the early morning hours. Imboden realized quickly that the train would not get underway until late in the day. Regimental and brigade surgeons and their staffs had to compile lists of the wounded, and physically gathering and loading all those who could be moved into the wagons was a monumental task. Across all units, every able-bodied soul—including band members, black servants, and drummer boys—were conscripted to gather the fallen and load them into the vehicles.13

Additional artillery, twenty-three pieces in all, arrived as did Brig. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee’s cavalry brigade, which had been ordered to cover the rear of the train. By noon on July 4, a torrential downpour blanketed South Mountain, adding to Imboden’s troubles and the agony of the wounded men.14 Imboden was fully cognizant of the crushing responsibility General Lee had placed on his shoulders. And per Lee’s instructions, Imboden resolved that once the train started, it would not halt until it reached its destination—even if that meant that disabled wagons had to be abandoned along the way.15

With the rain still pouring in sheets, soaking everything and turning roads into muddy gruel, the wagon train began moving toward Chambersburg at about 4:00 p.m. Luther Hopkins, a trooper of the 6th Virginia Cavalry, was resting on the ground while allowing his horse to graze along the Chambersburg Road when he heard “a low rumbling sound … resembling distant thunder, except that it was continuous.” Hopkins and a few of his comrades wondered what it was. They soon found out. “A number of us rose to our feet and saw a long line of wagons with their white covers moving … along the Chambersburg Road…. The wagons going back over the same road that had brought us to Gettysburg told the story, and soon the whole army knew that fact. This was the first time Lee’s army had ever met defeat.”16 The wagon train presented quite a sight. “It was the longest wagon train I ever saw,” recalled another Southerner, “some said it was 27 to 30 miles long.”17 A band member of J. Johnston Pettigrew’s Brigade saw it as “a motley procession of wagons, ambulances, wounded men on foot, straggling soldiers and band boys, splashing along in the mud, weary, sad and discouraged.”18

Imboden directed the operation from Cashtown. Detachments of guns and troops were inserted into the column at intervals of one-quarter to one-third of a mile.19 By the time the last wagons had joined the grim procession from Cashtown the following morning, the train stretched more than seventeen miles.20

Stuart’s cavalry division had hundreds of unserviceable mounts that had broken down at Gettysburg due to the fighting and hard riding. They had been corralled together, and those that could be taken along with the army were placed in an enormous column in the road, constituting, as one of Stuart’s troopers recalled, “a grand cortege of limping horses after the wagon train.” As the wagon wheels churned up the muddy roads in the monsoonal rains, the poor lame beasts had a progressively harder time keeping up. Those that couldn’t were left where they fell.21

Most of the wagons were of the “Conestoga” style, so named for the Pennsylvania valley in which they were built and perfected. Typically about eighteen feet long, most of the wagons had been built for rolling stock, and so able to hold six barrels of supplies in two rows of three each. They had no springs to cushion the forty-mile ride ahead. They also offered little or no protection from the downpour.22 Pvt. Robert James Lowry of Co. G, 3rd Arkansas Infantry, felt compassion for the plight of his comrades—especially since his brother, Sgt. John F. Lowry, was among the wounded. “Scarcely one in a hundred had received adequate medical care and most had not eaten in 36 hours,” Lowry explained. “The wagons did not have springs and the wounded lay on the bare boards.”23

“The rain fell in blinding sheets; the meadows were soon overflowed and fences gave way before the raging streams,” wrote Imboden. “During the storm, wagons, ambulances, and artillery carriages by hundreds—nay, by thousands—were assembling in the fields along the road from Gettysburg to Cashtown, in one confused and apparently inextricable mass. As the afternoon wore on there was no abatement in the storm. Canvas was no protection against its fury, and the wounded men lying upon the naked boards of the wagon-bodies were drenched.”24 The sounds of the tempest nearly drowned out the agonized cries of the wounded. “Horses and mules were blinded and maddened by the wind and water, and became almost unmanageable,” continued the cavalry leader. “The deafening roar of the mingled sounds of heaven and earth all arou...