eBook - ePub

Indian War Veterans

Memories of Army Life and Campaigns in the West, 1864–1898

- 624 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The decades-long military campaign for the American West is an endlessly fascinating topic, and award-winning author Jerome A. Greene adds substantially to this genre with Indian War Veterans: Memories of Army Life and Campaigns in the West, 1864-1898. Greene's study presents the first comprehensive collection of veteran (primarily former enlisted soldiers') reminiscences. The vast majority of these writings have never before seen wide circulation. Indian War Veterans addresses soldiers' experiences throughout the area of the trans-Mississippi West. As readers will quickly discover, the depth and breadth of coverage is truly monumental. Topics include recollections of fighting with Custer and the mutilation of the dead at Little Bighorn, the Fetterman fight, the Yellowstone Expedition of 1873, battles at Powder River and Rosebud Creek, fighting Crazy Horse at Wolf Mountains, Geronimo and the Apache wars, the Ute and Modoc wars, Wounded Knee, and much more. The remembrances also include selections as diverse as "Christmas at Fort Robinson," "Service with the Eighteenth Kansas Volunteer Cavalry," and "Chasing the Apache Kid." These carefully drawn recollections derive from a wide array of sources, including manuscript and private collections, veterans' scrapbooks, obscure newspapers, and private veterans' statements. A special introductory essay about Indian war veterans contains new material about their post-service organizations all the way into the 1960s. Complimenting the riveting entries are dozens of previously unpublished photographs. Readers will additionally find a gallery of never-before-seen full-color plates displaying a wide variety of Indian War Veterans' badges, medals, and associated materials. No other book discusses the post-army lives of these men or presents their recollections of army life as thoroughly as Greene's Indian War Veterans. This groundbreaking study will appeal to lay readers, historians, site visitors and interpreters, Civil War and Indian wars enthusiasts, collectors, museum curators, and archeologists. "A treasure-trove of original sources on the Indian wars, an essential addition to every library on the subject." --Paul A. Hutton, University of New Mexico, and the author of "Phil Sheridan and his Army and "The Custer Reader." About the Author: Jerome A. Greene is an award-winning author and historian with the National Park Service. His books include The Guns of Independence: The Siege of Yorktown, 1781, Lakota and Cheyenne: Indian Views of the Great Sioux War, 1876-1877, Morning Star Dawn: The Powder River Expedition and the Northern Cheyenne, 1876, and Washita: The U.S. Army and the Southern Cheyennes, 1867-1869. He resides in Colorado.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Indian War Veterans by Jerome A. Greene in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 19th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

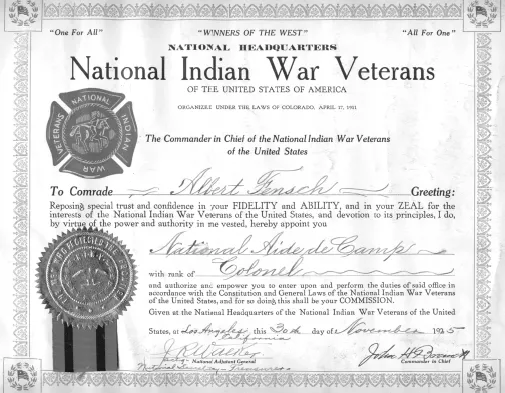

Commission certificate appointing Albert Fensch as National Aide-de-Camp of the National Indian War Veterans and signed by Commander-in-Chief John H. Brandt in Los Angeles, 1925. Editor's Collection.

Preface and Acknowledgments

This book comprises a reader embracing significant personal accounts by army veterans of their life and service on the trans-Mississippi frontier during the last four decades of the nineteenth century, the core period of Indian-white warfare in that region. The essays are drawn from various sources, each as indicated, but with most from the constituency of the National Indian War Veterans Association via the group’s periodical tabloid, Winners of the West. The first articles, those dealing with veterans’ reminiscences of their routine day-to-day experiences on the frontier, are presented in chronological order. Those describing elements of campaign and warfare history are arranged chronologically within geographical areas of the West and constitute the largest part of the book. A few of these essays have appeared elsewhere, although none have previously been widely disseminated.

In all instances, the intent has been to reproduce the content of each essay so that readers might derive the author’s original meaning clearly and comprehensively, despite obvious variances in writing technique and ability. Occasionally, minor grammatical, punctuation, and spelling changes have been introduced editorially without brackets to improve readability. Rarely, too, words have been interjected to complete and improve factual representations, such as in giving an individual’s full name and/or military rank. (Infrequently, for example, authors of some pieces have referenced brevet or honorary rank in introducing officers, and this has been consistently corrected to reflect proper Regular Army rank usage throughout.) In no way has the substance of an article been altered or otherwise miscast. Footnotes have been scrupulously avoided in the essays for the purpose of insuring an uninterrupted reading experience.

While an ex-soldier might occasionally exaggerate recollected facts or conditions, he might also make factual errors, and in such instances bracketed insertions have been made to correct grievously erroneous data. Also brackets have been used sparingly wherever brief introductory, transitional, and clarifying material was deemed appropriate. In most instances, the titles of individual essays have been changed from the headline format of the original presentations to better convey the content of each. And wherever parts of an article wavered from its purpose or became irrelevant to its subject, those parts were omitted and their omission indicated with ellipses. Finally and importantly, as testimony reflective of the periods during which the veterans performed their service (the 1860s-1890s) and later wrote their pieces (generally the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s), the references to Indians are often disparaging and occasionally brutally racist. As such, the remarks mirror a temper of thought grounded in ignorance that existed during those times. However objectionable they seem today, they nonetheless provide useful insights into the thinking of this element of early twentieth-century American society, and they have not been sanitized herein.

I wish to acknowledge the following individuals and institutions for their assistance in this project: L. Clifford Soubier, Charles Town, West Virginia; Douglas C. McChristian, Tucson, Arizona; John D. McDermott, Rapid City, South Dakota; James B. Dahlquist, Seattle, Washington; Thomas R. Buecker, Crawford, Nebraska; R. Eli Paul, Kansas City, Missouri; Paul L. Hedren, O’Neill, Nebraska; John Doerner, Hardin, Montana; James Potter, Chadron, Nebraska; David Hays, Boulder, Colorado; Gordon Chappell, San Francisco, California; Dick Harmon, Lincoln, Nebraska; John Monette, Louisville, Colorado; Paul Fees, Cody, Wyoming; Judy M. Morley, Centennial, Colorado; Robert G. Pilk, Lakewood, Colorado; Paul A. Hutton, Albuquerque, New Mexico; Neil Mangum, Alpine, Texas; Douglas D. Scott, Lincoln, Nebraska; Thomas Gilcrease Institute of American History and Art, Tulsa, Oklahoma; Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, Crow Agency, Montana; and Jack Blades of Night Ranger. Special thanks go to Sandra Lowry, Fort Laramie National Historic Site, Wyoming, for her help in providing full and correct names for many of the enlisted men mentioned herein.

My thanks are also extended to everyone at Savas Beatie who helped get this book into print.

Introduction

The Indian War Veterans, 1880s-1960s

They called themselves the “Winners of the West.” They were the soldier veterans of the U. S. Army and state and territorial forces in the West, many of them survivors of Indian campaigns between 1864 and 1898, and they regarded themselves as the vanguards of civilization on the frontier. Some had fought Sioux, Cheyenne, Nez Perce, Comanche, Kiowa, and Apache warriors at renowned places like Washita, Apache Pass, Rosebud, Little Bighorn, White Bird Canyon, Bear’s Paw Mountains, and Wounded Knee, although the majority who also claimed to be Indian war veterans had performed more routine and unheralded duties during their years beyond the Mississippi River.

While in many ways their service facilitated the economic exploitation of Indian lands wrought by mining and settlement, as well as the internment of the tribes on reservations that followed, like most Americans of the time they embraced concepts of Manifest Destiny, by which they justified their own and their government’s actions. Most of them were former enlisted men, drawn together by camaraderie but also for the purpose of bettering living conditions for themselves and their families by championing pension benefits from a seemingly distant and unsympathetically frugal federal government that had extended its largess more charitably to the disabled veterans of the Civil War and the Spanish-American War.

The creation of associations specific to the interests of Indian war veterans followed a course similar to that of other veterans’ groups after the period of focus their service represented. Groups composed of veteran officers generally reflected their fraternal interests, as did, for example, the Society of the Cincinnati for those who served in the Revolutionary War; the Society of the War of 1812; the Aztec Club for former Mexican War officers; the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States for former Civil War officers; and several smaller societies observing officer service in Cuba, the Philippines, and China late in the nineteenth century.1

Enlisted veteran organizations, generally more concerned with welfare issues, had roots in various municipal and regional relief organizations founded during the Civil War to help needy soldiers and which continued to promote relief programs after the war. In the immediate postwar years, a profusion of groups evolved that eventually (1866-69) merged into a single association, the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) that included both former Union officers and enlisted men. (A parallel and smaller body, the United Confederate Veterans, later served the interests of those who had fought for the South.)

Much of the GAR’s purpose was to provide for the well-being of members and their families, objectives espoused by the Republican Party in the final decades of the nineteenth century, and the organization, which became sizable (400, 000 members by 1890) came to register significant political clout. In time, the GAR’s rolls gradually fell, and its influence waned during the early decades of the twentieth century; the last annual encampment took place in 1949.

A group formed to promote similar interests for its constituency was the United Spanish War Veterans, which shared ideals of the GAR as applied to officers and enlisted men who had served in the Spanish-American War of 1898, the Philippine Insurrection that followed, and the China Relief Expedition of 1900. Like the GAR, the USWV resulted from the merger of kindred bodies between 1904 and 1908. The goals of the GAR, meantime, inspired the birth of organizations of similar spirit dedicated to the interests of soldiers and sailors whose service postdated the Civil War. In 1888-90, from several such fledgling groups, the Regular Army and Navy Union was founded, mainly by veterans of duty in the postwar West, to provide like needs for soldiers, sailors, and marines without Civil War service, including those yet serving or retired from active duty. In the late 1880s and through the 1890s, garrisons or camps of the Regular Army and Navy Union flourished in cities around the country, as well as at various active army posts.2

Inspired by these various groups, and desirous of coming together for collateral purposes based upon their shared background and experiences, during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries the ex-soldiers of the so-called Indian wars period (ca. 1865-1891) began organizing into several bodies reflective of their common service. With their small and ever-decreasing base, however, they never attained the political strength of the GAR, whose large membership influenced pension legislation as well as the outcome of congressional and presidential elections from the 1870s well into the twentieth century. (Much the same was true of similar bodies of Spanish-American War and World War I veterans.) Beset by limited numbers and resources, the Indian war veterans shared fellowship, longevity, and perseverance, and played much the role of other veterans’ groups in sharing reminiscences of their army life, seeking to improve government benefits (albeit with considerably less success), promoting patriotism, and otherwise ensuring that citizens did not lose sight of their contributions to the nation.

The first organization of Indian war veterans was hereditary and fraternal, consisting of retired officers and select enlisted personnel who had shared experiences on the frontier and whose meetings reflected collegiality and an interest in preserving the history of the Indian wars of the trans-Mississippi West for future generations. On April 23, 1896, a group of active and retired army officers convened at the United Service Club in Philadelphia to organize the Society of Veterans of Indian Wars of the United States. Its constitution designated three classes of members consisting of First Class (“Commissioned officers…who have actually served or may hereafter serve in the Army during an Indian War…[including] any officer of a State National Guard or Militia meeting the above requirements….”); Second Class (“Lineal male descendants of members of the first class,” or male descendants of officers who were eligible “but who died without such membership”); and Third Class (Non-commissioned officers and soldiers who have received the Medal of Honor or Certificate of Merit from the United States Government…or who have been proffered, or recommended for, a commission, or who have been specially mentioned in orders by the War Department or their immediate commanding officer for services rendered against hostile Indians….” Charter members of the society included William F. (“Buffalo Bill”) Cody, who was a colonel in the Nebraska National Guard, and retired Captain Charles King, the army novelist who had campaigned against the Apaches and Lakotas under Brigadier General George Crook.3

For reasons not altogether clear, the Society of Veterans of Indian Wars almost immediately evolved into the Order of Indian Wars of the United States, under which title it functioned for nearly fifty years. Chartered in Illinois just months after the Philadelphia meeting, the stated purpose of the group was “to perpetuate the memory of the services rendered by the American Military forces in their conflicts and wars within the territory of the United States, and to collect and secure for publication historical data relating to the instances of brave deeds and personal devotion by which Indian warfare has been illustrated.” Membership was restricted to “commissioned officers and honorably discharged commissioned officers of the U. S. Army, Navy and Marine Corps, and of State and Territorial Military Organizations…who have been, or who hereafter may be engaged in the service of the United States…in conflicts, battles or actual field service against hostile Indians within the jurisdiction of the United States….” The organization also accommodated inclusion of male descendants and provided for honorary and associate memberships.

On January 14, 1897, a meeting of the Order in Chicago elected the first national officers, including as commander retired Ninth Cavalry Lieutenant Colonel Reuben F. Bernard. Later commanders included such formerly prominent retired Indian wars officers as Brigadier General Anson Mills, Brigadier General Leonard Wood, Brigadier General Edward S. Godfrey, Major General Hugh L. Scott, and Lieutenant General Nelson A. Miles. During its half century of existence, the Order of Indian Wars performed valuable commemorative and historical services through its annual dinner meetings, usually held at the Army and Navy Club in Washington, D. C. At a standard gathering, members discussed the Order’s business then listened as a companion presented a formal paper on an aspect of Indian wars history based largely on his service. The proceedings were generally published and today constitute important historical data of the organization and the era it memorialized. Among the trappings of the society were vellum membership certificates signed by the commander. They bore an elaborate engraving of troops attacking an Indian village, as well as an elitist-sounding sentiment honoring members for “maintaining the supremacy of the United States.”

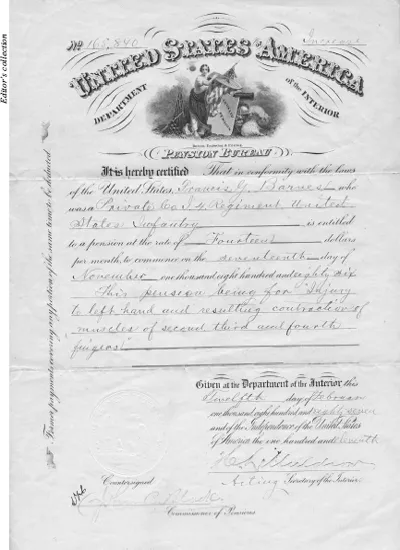

Pension certificate granted in 1887 to former private Francis G. Barnes, Company I, Fourth Infantry. Barnes’s pension was for “Injury to left hand and resulting contraction of muscles of second, third and fourth fingers,” for which he was awarded fourteen dollars per month. Barnes died in 1921 in Hamburg, New York.

The Order of Indian Wars was most active during the 1910s, 1920s, and early 1930s. Membership peaked at 376 in 1933. By the 1940s, deat...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Books by Jerome A. Greene

- Contents

- Dedication 1

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- Introduction The Indian War Veterans, 1880s-1960s

- Part I: Army Life in the West

- Part II: Battles and Campaigns

- Suggested Reading

- Notes

- Index

- About the Author