eBook - ePub

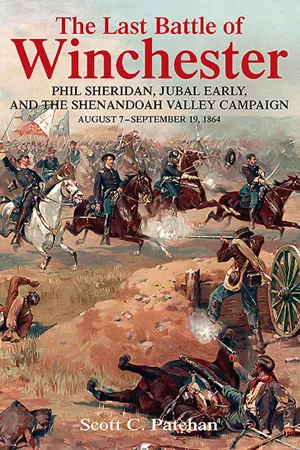

The Last Battle of Winchester

Phil Sheridan, Jubal Early, and the Shenandoah Valley Campaign, August 7–September 19, 1864

- 576 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Last Battle of Winchester

Phil Sheridan, Jubal Early, and the Shenandoah Valley Campaign, August 7–September 19, 1864

About this book

"Unique insight, good storytelling skills, deep research, and keen appreciation for the terrain . . . one outstanding work of history." —Eric J. Wittenberg, award-winning author of

Gettysburg's Forgotten Cavalry Actions

The Third Battle of Winchester in September 1864 was the largest, longest, and bloodiest battle fought in the Shenandoah Valley. What began about daylight did not end until dusk, when the victorious Union army routed the Confederates. It was the first time Stonewall Jackson's former corps had ever been driven from a battlefield, and their defeat set the stage for the final climax of the Valley Campaign. This book represents the first serious study to chronicle the battle.

The Northern victory was a long time coming. After a spring and summer of Union defeat in the Valley, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant cobbled together a formidable force under Phil Sheridan, an equally redoubtable commander. Sheridan's task was a tall one: sweep Jubal Early's Confederate army out of the bountiful Shenandoah, and reduce the verdant region of its supplies. The aggressive Early had led the veterans of Jackson's Army of the Valley District to one victory after another at Lynchburg, Monocacy, Snickers Gap, and Kernstown.

Five weeks of complex maneuvering and sporadic combat followed before the opposing armies met at Winchester, an important town that had changed hands dozens of times over the previous three years. Tactical brilliance and ineptitude were on display throughout the daylong affair as Sheridan threw infantry and cavalry against the thinning Confederate ranks and Early and his generals shifted to meet each assault. A final blow against Early's left flank finally collapsed the Southern army, killed one of the Confederacy's finest combat generals, and planted the seeds of the victory at Cedar Creek the following month.

This vivid account—based on more than two decades of meticulous research and an unparalleled understanding of the battlefield, and rich is analysis and character development—is complemented with numerous original maps and explanatory footnotes that enhance our understanding of this watershed battle.

The Third Battle of Winchester in September 1864 was the largest, longest, and bloodiest battle fought in the Shenandoah Valley. What began about daylight did not end until dusk, when the victorious Union army routed the Confederates. It was the first time Stonewall Jackson's former corps had ever been driven from a battlefield, and their defeat set the stage for the final climax of the Valley Campaign. This book represents the first serious study to chronicle the battle.

The Northern victory was a long time coming. After a spring and summer of Union defeat in the Valley, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant cobbled together a formidable force under Phil Sheridan, an equally redoubtable commander. Sheridan's task was a tall one: sweep Jubal Early's Confederate army out of the bountiful Shenandoah, and reduce the verdant region of its supplies. The aggressive Early had led the veterans of Jackson's Army of the Valley District to one victory after another at Lynchburg, Monocacy, Snickers Gap, and Kernstown.

Five weeks of complex maneuvering and sporadic combat followed before the opposing armies met at Winchester, an important town that had changed hands dozens of times over the previous three years. Tactical brilliance and ineptitude were on display throughout the daylong affair as Sheridan threw infantry and cavalry against the thinning Confederate ranks and Early and his generals shifted to meet each assault. A final blow against Early's left flank finally collapsed the Southern army, killed one of the Confederacy's finest combat generals, and planted the seeds of the victory at Cedar Creek the following month.

This vivid account—based on more than two decades of meticulous research and an unparalleled understanding of the battlefield, and rich is analysis and character development—is complemented with numerous original maps and explanatory footnotes that enhance our understanding of this watershed battle.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Last Battle of Winchester by Scott C. Patchan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Histoire & Histoire de la guerre de Sécession. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

WORTH HIS WEIGHT IN GOLD

Sheridan, Grant, Lincoln, and Union Strategy in the Shenandoah Valley

Shrill blasts from a train whistle pierced the air around Monocacy Junction to announce the arrival of the new commander of the Army of the Shenandoah. When Maj. Gen. Philip Henry Sheridan stepped onto the station platform, his future was as unclear as the smoke wafting along the tracks. His prospect for achieving victory in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley seemed unlikely. The history of the Union’s fortunes in that “Valley of Humiliation,” coupled with Sheridan’s inexperience as an army commander, provided little reason to believe otherwise. To most, it seemed more probable that he would soon join the long list of Union generals whose careers derailed in the Shenandoah Valley. Sheridan, however, had the confidence of his commander, Lt. Gen. Ulysses Simpson Grant, and every promotion received bore the date of a hard fought battle.

In an age when martial pomp, flamboyant uniforms, and dramatic proclamations were commonplace among men of high military rank, this unspectacular little Irish-American from Ohio hardly fit anyone’s image of an ideal general. But then again, neither did Grant. President Abraham Lincoln initially saw only “a brown, chunky little chap, with a long body, short legs, not enough neck to hang him, and such long arms that if his ankles itch he can scratch them without stooping.” Indeed, Sheridan stood only five-feet-five-inches tall and weighed a slight 115 pounds. Crowned with a black, flat-topped, pork-pie hat, he donned the simple blue coat of the common soldier only slightly embellished by regulation shoulder straps bearing the two stars of a major general. “There was nothing about him to attract attention,” observed a reporter, “except his eye … that seemed a black ball of fire.” Grant had seen that fire blazing on the battlefield at Chattanooga, and it was exactly what he wanted in the Shenandoah Valley.1

In an age of fierce anti-Catholic and anti-Irish prejudice in America, Sheridan’s family heritage contrasted sharply from the lineage of the typical U.S. Army officer. Men of rank were chiefly composed of Anglo-Saxon Protestants from the aristocratic South or gentry from the Mid-Atlantic and New England states. While he claimed birth in America, some evidence indicates that Sheridan may have been born during his family’s trans-Atlantic voyage or even back in Killinkere Parish, County Cavan, Ireland. Generations before his birth, the English had brutally repressed the native Irish Catholics and attempted to repopulate the area with lowland Scots and English settlers. Nevertheless, the Sheridan family and its forebears steadfastly adhered to their religious beliefs as they struggled to eke out a living on a small leased tract, land that centuries before had been taken from the Irish by the English. Oppression and limited economic opportunities finally induced the family’s immigration to the United States in 1831, the year of Philip’s birth. After spending time in Boston and Albany, the family moved west, settling in the then frontier town of Somerset, Ohio. Nestled in the rolling green hills of southeastern Ohio, this small town had become a haven for Irish Catholics who had flocked there to work construction jobs along the ever expanding National Road.2

Life in Ohio was not easy for the Sheridans. Like most people of that era, the daily routine revolved around providing for necessities of life. Philip’s father, John, worked as a laborer on the National Road but still struggled to support his wife Mary Meenagh and their children. There were no servants at the Sheridan home so “Little Phil,” as he became known, performed daily chores around the family’s modest three-room log cabin. With his father away from home working on the construction crews, Sheridan’s mother provided his “sole guidance.” He later acknowledged that her “excellent common sense and clear discernment in every way fitted her for such maternal duties.” He received only the bare basics of an education in a one-room schoolhouse. The Irish schoolmaster, a Mr. McManly, “one of those itinerant dominies of the early frontier,” as Sheridan recalled him, fully implemented the old adage that “to spare the rod was to spoil the child.” When in doubt, the schoolmaster “would consistently apply the switch to the whole school,” thus never failing to catch the miscreant. Even worse for young Phil, McManly was an old acquaintance of his mother from the days in Ireland, so he paid particular attention to the development of her son.3

Young Sheridan longed for a military career. Like so many boys, he was captivated by martial pomp and circumstance. Somerset’s annual Fourth of July celebrations provided him with the perfect opportunity to experience American military history in the flesh. When Sheridan was six or seven years old, the event’s organizers rolled out an aged Revolutionary War veteran “in a farmer’s wagon, seated on a split-bottom chair.” When Phil saw the crowd eagerly gathering around the veteran and leading him to a place of honor on the platform, Sheridan asked a friend, Henry Greiner, why everyone was making such a fuss over the man. Upon hearing that he “had been a soldier under Washington” and had fought in five battles, Sheridan transfixed his eyes upon that living piece of history. “I never saw Phil’s brown eyes open so wide or gaze with such interest as they did on this old revolutionary relic,” recalled Greiner. Seeing this “comrade of Washington … was probably the first glow of military emotion that he experienced.” Thereafter, Sheridan spent long hours watching the local militia drill in the town square, dreaming of the day that he would lead men into battle. “Little Phil” evidently impressed the people of Somerset in that regard. An elderly friend actually crafted a tin sword for the boy that was used to lead companions in mock military drills and battles.4

Living along the National Road allowed Philip to meet a host of characters, few of whom were as colorful as the tough-talking teamsters seeking a brief respite in Somerset after a long haul. Their rough language and combative tenacity impressed the young Sheridan, who later emulated their style on many a Civil War battlefield. Although he was very small in stature, the boys of Somerset quickly learned that his fierce Irish temper compensated for his diminutive proportions in a brawl. Many of these fights were the outgrowth of a generations-old cross-town rivalry. Sheridan and his comrades of the vaunted “Pig Feet” gang battled their adversaries, the “Turkey Feet” in Somerset’s adolescent turf wars, even though the cause of the rivalry had been long forgotten.5

Although stories of his boyhood high jinks were widely told after Sheridan became a national hero, he successfully completed his formal schooling at just 14. The time had come to find his station in life. Many years of firsthand observation had convinced a local businessman and neighbor that Sheridan was an intelligent and dependable youth with the potential to do much more with his life than the average boy from Somerset. Sheridan jumped at the opportunity to work with the merchant, but was also encouraged to “improve himself” through further study in “mathematics [and] select works of history.” While Philip excelled as a storekeeper, he longed for what he believed was a more exciting career in the U.S. Army. After three years of clerking, Sheridan applied for an opening to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point from Somerset’s congressional district. “There came a letter, accompanied by no testimonials, no influential recommendations, or appeals from wealthy parents,” recalled Sheridan’s Congressman Thomas Ritchey. “It simply asked that the place might be given to the writer, and was signed ‘Phil Sheridan.’ The boy needed no recommendations, for I knew him and his father before him, and I appointed him at once.” The opportunity to live his dream had arrived.6

At West Point, Sheridan discovered that his Irish-Catholic heritage and working-class roots set him apart from an academy dominated by cadets from the South and the eastern seaboard cities. Further, a large segment of the cadet corps was pro-slavery, a doctrine Sheridan was unwilling to tolerate. These differences, combined with his inborn sharp temper, resulted in “various collisions” with fellow his cadets. The hot-headed Ohioan resented “even the appearance of an insult”—even if he knew the resulting altercation would end with his classmates carrying him back to his quarters. On one occasion he assaulted a Virginian in front of the entire company of cadets. This action resulted in a one-year suspension and delayed his graduation. Ironically, the Virginian, James Terrill, would remain loyal to the Union in 1861, fight with Sheridan in the Army of the Ohio, and die in battle at Perryville, Kentucky, in October 1862. In spite of the culture clash in upstate New York and his intemperate actions, Sheridan graduated in 1853 ranked 35th of 53. Following graduation, Sheridan entered the infantry, where he served for eight years in Texas and Oregon, gaining some combat and leadership experience fighting Indians.7

Sheridan was serving in Oregon with the 4th U.S. Infantry when Southern forces opened fire on Fort Sumter in April 1861. Just as it did for thousands of other men, the war presented Sheridan with an opportunity for career advancement, and he intended to take full advantage of the chance. The fiery Ohioan, recalled a subordinate, “believed intensely that rebellion was a crime, and that it ought to be put down, no matter what the cost.”8 To Sheridan’s dismay, he remained in Oregon until the fall of 1861 when orders finally arrived assigning him to the 13th U.S. Infantry. The journey to Jefferson Barracks in Missouri was a long one. Sheridan left Fort Yamhill in Oregon by ship and sailed to San Francisco. From there he sailed to the Isthmus of Panama, which he crossed to catch another ship north to New York City. After a brief sojourn back home in Somerset, Sheridan made his way to St. Louis. Upon his arrival, Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck, then commander of the Department of the Missouri, selected Sheridan for staff work.9

One of the first tasks Halleck assigned Sheridan was auditing the fiscal mess and cleaning up rampant corruption in Maj. Gen. John C. Fremont’s Department of Missouri. Sheridan called upon his years of experience as a store clerk back in Ohio and approached the assignment with methodical steadfastness, displaying the same diligence and dedication he would later bring to planning military campaigns. After successfully completing the audit, Halleck rewarded Sheridan with an appointment as the chief quartermaster and commissary of the Army of Southwest Missouri under Maj. Gen. Samuel Curtis. At the time, Curtis’s army was conducting the Pea Ridge campaign, and Sheridan’s efforts proved critical. The position provided Sheridan with a firm understanding of the importance of logistics and supply to an army in the field. This knowledge would profoundly influence his decisions during the 1864 Shenandoah Valley campaign.

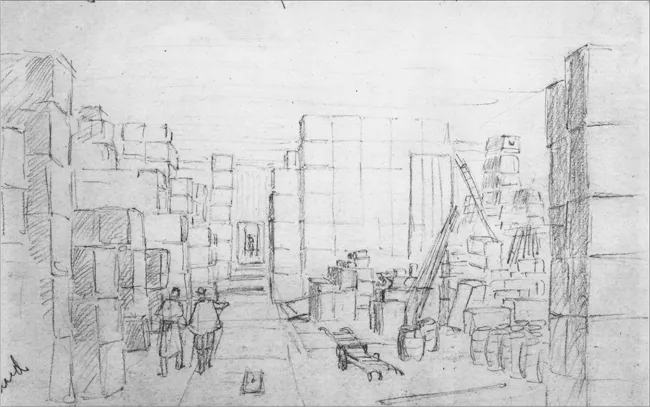

Warehouse in Harpers Ferry containing Quartermaster stores for Sheridan’s Army. A. R. Waud, LC

It did not take long for Sheridan to run afoul of the irascible Curtis. The confrontation was set in motion when officers in the quartermaster’s department requested payment from Sheridan for horses they had stolen from civilians. The Ohioan refused their demand and, instead, confiscated the animals for army use. The rebuffed officers were allied with Curtis and unwilling to go away empty-handed. When they complained about Sheridan’s actions, the army commander ordered payment of the claims. Sheridan stood by his decision and refused. “No authority can compel me to jay hawk or steal,” he argued. “If those under my supervision are allowed to do so, I respectfully ask the General to relieve me from duty in his district as I am of no use to the service here, unless, I can enforce my authority.”10 General Curtis was outraged and leveled charges against Sheridan; however, the proceedings stopped short of a full court-martial when General Halleck interceded on the Ohioan’s behalf and returned him to staff duty.

After the Confederate defeat at the battle of Shiloh in April 1862, Sheridan served as an assistant to General Halleck’s topographical engineer during the army’s snail-like advance toward the important logistical center of Corinth, Mississippi. In reality, Sheridan carried out any number of functions around headquarters and on the march. No matter the task, he approached it with his trademark “intense earnestness that made his success.” Sheridan still longed for a combat command, but an appointment did not appear imminent. Even the influential Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman was unable to secure a commission for “Little Phil.” Several fellow officers, including Brig. Gen. Gordon Granger and Capt. Russell Alger, lobbied the governor of Michigan to appoint Sheridan as colonel of the 2nd Michigan Cavalry. Despite his lack of mounted experience, the officers helped secure the appointment on May 27, 1862. General Halleck reluctantly approved the promotion, although he regretted losing such an efficient staff officer. Halleck later joked that no one could pitch headquarters tents as well as Sheridan.11

Sheridan’s first combat opportunity arrived several weeks later on July 1, 1862, during one of the few pitched conflicts of the Corinth operation. He led a small brigade of 900 troopers to victory over several thousand Confederate horsemen at Booneville, Mississippi. His cleverness, innovative tactics, and outstanding intelligence work impressed Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans, commander of the Army of the Mississippi. He promptly urged the Ohioan’s promotion to general. “Brigadiers scarce. Good ones scarcer,” declared Rosecrans, “and the undersigned respectfully beg that you will obtain the promotion of Sheridan. He is worth his weight in gold.” Sheridan was promoted to brigadier general on September 13, 1862, to rank from the date of his success at Booneville.12

Although Sheridan emerged from the war with the exalted reputation as the Union’s leading cavalryman, his true legacy was as the Union’s premier front line combat commander. More than a dozen years after the war, sculptor James E. Kelly complimented Sheridan’s countenance as having “the character of the cavalryman.” In an unguarded, spontaneous response, Sheridan retorted, “Yes, yes, but I commanded infantry.” His promotion landed him command of an infantry division in Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio. At Perryville, Kentucky, on October 8, 1862, Sheridan displayed prudent aggressiveness and a willingness to act independently as the situation demanded. His real baptism of fire occurred on December 31, 1862, during the first day’s fighting at the battle of Stones River outside Murfreesboro, Tennessee. Suspecting that a Confederate attack was imminent, Sheridan placed his division under arms at an early hour and readied it for action. When the attack came, the Southerners drove the unprepared divisions on his right from the field. Sheridan, h...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction and Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1 Sheridan, Grant, Lincoln, and Union Strategy in the Shenandoah Valley

- Chapter 2 Jubal Early and Confederate Strategy

- Chapter 3 Sheridan, Early, and their Subordinate Commanders

- Chapter 4 Sheridan Moves Against Early

- Chapter 5 The Battle of Guard Hill (Crooked Run)

- Chapter 6 Confederate Resurgence, August 17 – 19

- Chapter 7 Confederate Charlestown Offensive, August 21

- Chapter 8 Halltown to Kearneysville, August 22 – 25

- Chapter 9 Halltown to Smithfield, August 26 – 29

- Chapter 10 The Battle of Berryville, September 3

- Chapter 11 Advance and Retreat, September 3 - 15

- Chapter 12 Prelude to Battle, September 15 - 18

- Chapter 13 The Battle of Opequon Creek, September 19

- Chapter 14 The Berryville Pike 229

- Chapter 15 The Middle Field and the Second Woods

- Chapter 16 Russell and Dwight Restore the Union Line

- Chapter 17 The U.S. Cavalry Advance

- Chapter 18 Crook’s Attack

- Chapter 19 The Final Union Attack

- Chapter 20 Confederate Collapse

- Chapter 21 Winchester to Fisher’s Hill and Beyond

- Chapter 22 One of the Hardest Fights on Record

- Appendix 1 Union and Confederate Orders of Battle

- Appendix 2 The Army of the Shenandoah Strength Reports

- Appendix 3 The Army of the Valley District Strength Reports

- Appendix 4 Casualties in the Army of the Shenandoah

- Appendix 5 Casualties in the Army of the Valley District

- Appendix 6 Medals of Honor Awarded, August 16 to September 19, 1864

- Appendix 7 Select Soldier Accounts of the Shenandoah Valley Campaign

- Bibliography

- Index