- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

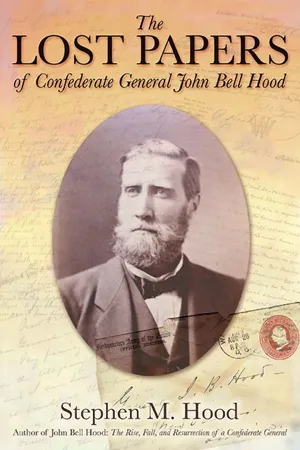

The Lost Papers of Confederate General John Bell Hood

About this book

Scholars hail the find as "the most important discovery in Civil War scholarship in the last half century." The invaluable cache of Confederate General John Bell Hood's personal papers includes wartime and postwar letters from comrades, subordinates, former enemies and friends, exhaustive medical reports relating to Hood's two major wounds, and dozens of touching letters exchanged between Hood and his wife, Anna. This treasure trove of information is being made available for the first time for both professional and amateur Civil War historians in Stephen "Sam" Hood's The Lost Papers of Confederate General John Bell Hood. The historical community long believed General Hood's papers were lost or destroyed, and numerous books and articles were written about him without the benefit of these invaluable documents. In fact, the papers were carefully held for generations by a succession of Hood's descendants, and in the autumn of 2012 transcribed by collateral descendent Sam Hood as part of his research for his book John Bell Hood: The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of a Confederate General (Savas Beatie, 2013.) This collection offers more than 200 documents. While each is a valuable piece of history, some shed important light on some of the war's lingering mysteries and controversies. For example, several letters from multiple Confederate officers may finally explain the Confederate failure to capture or destroy Schofield's Union army at Spring Hill, Tennessee, on the night of November 29, 1864. Another letter by Lt. Gen. Stephen D. Lee goes a long way toward explaining Confederate Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne's gallant but reckless conduct that resulted in his death at Franklin. Lee also lodges serious allegations against Confederate Maj. Gen. William Bate. While these and others offer a military perspective of Hood the general, the revealing letters between he and his beloved and devoted wife, Anna, help us better understand Hood the man and husband. Historians and other writers have spent generations speculating about Hood's motives, beliefs, and objectives, and the result has not always been flattering or even fully honest. Now, long-believed "lost" firsthand accounts previously unavailable offer insights into the character, personality, and military operations of John Bell Hood the general, husband, and father.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Lost Papers of Confederate General John Bell Hood by Stephen M. Hood in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Histoire & Histoire du 19ème siècle. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

John Bell Hood: Son and Soldier

Historians in general don’t agree on very much, and Civil War historians offer no exception to this. The rather enigmatic career of Confederate Gen. John Bell Hood, however, brings together both detractors and supporters of Hood on one point: the life and career of the native Kentuckian was one of the most extraordinary in American military history. The details of his career—especially his 1864 tenure as both an infantry corps leader and army commander—often cleave apart any degree of civil concurrence. Most students of the Civil War rank Hood’s tenure at the head of the Army of Tennessee near or at the bottom of any list of army commanders. Recent scholarship by Stephen Davis, Russell Bonds, Thomas Brown, and Eric Jacobson has rehabilitated Hood to some extent, but the influence of Hood’s earlier critics remains deeply entrenched in modern Civil War history.1

Hood’s meteoric rise and precipitous fall mimicked that of the Confederate States of America. His string of remarkable success at the head of the acclaimed Texas Brigade (which would forever bear his name) in Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia in 1862 and 1863 earned him plaudits in the Confederate high command. His personal bravery became legendary, making him a celebrity in Richmond society. He was a genuine public hero, and a favorite of the Confederate government. Both Hood and the Confederacy he served arguably reached their apex during the summer of 1863 when Lee’s invading army marched into Pennsylvania on its second incursion north of the Mason-Dixon Line. Late on the afternoon of July 2 at Gettysburg, Hood initiated a large assault against the left-front of the Army of the Potomac when he ordered forward his veteran infantry division. Just minutes later an artillery shell exploded above him and its fragments ripped into his left arm. Hood had suffered his second combat wound and his first of the Civil War.2 Unfortunately for the Southern cause, the attack failed, the Union army repelled the Rebels on both this day and the next, and Lee was decisively defeated.

Although commonly associated with Texas troops, Hood was not a native of the Lone Star State. The dashing and charismatic Hood was born in Bath County, Kentucky, in the small town of Owingsville on June 29, 1831, and raised in the rural Montgomery County community of Reid Village near Mount Sterling. The young Hood was heavily influenced by his two grandfathers, one an old veteran of the French and Indian War and the other a veteran of the American Revolution. These men were his primary male influences during the late 1820s and early 1830s while his father John W. Hood, a well educated rural doctor, made frequent trips to Pennsylvania to study medicine at the Philadelphia Medical Institute under a prominent physician believed to be John Bell Hood’s namesake, Dr. John Bell.3

Philadelphia’s Dr. Bell, a native of Ireland, had studied medicine in Europe and in 1821 attended commencement ceremonies at Transylvania College (now Transylvania University) in Lexington, Kentucky, near the Winchester, Kentucky, home of the aspiring young doctor John W. Hood. Since John W. Hood’s two older brothers were also physicians, it is possible the future Dr. John W. Hood met Dr. John Bell in Kentucky in 1821.4

In addition to teaching at the Philadelphia Medical Institute from 1829 to 1860, Dr. Bell also lectured on anatomy at Philadelphia’s Academy of Fine Arts, was a member of the Pennsylvania College of Physicians, the Kappa Lambda Medical Society, and served as editor of the Journal of Health. It would be understandable that young Dr. Hood of Kentucky was impressed with his mentor and teacher, the esteemed Dr. John Bell, and would honor him by naming one of his sons after him.5

The adventurous life of a soldier appealed to the young Hood, who gained an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1849. It is there that Hood received his nickname “Sam.” Although no known written explanation for the source of his nickname exists, many of his modern descendants believe he was given the moniker by his classmates after the famous British war hero, Admiral Samuel Hood (1724-1816), Viscount of Whitley, whose naval exploits in the late eighteenth century may have been studied by West Point students. After barely avoiding expulsion because of excessive demerits, Hood graduated in 1853 in the the bottom quintile of his class (44 out of 52 in a class that began with 96) and was commissioned a second lieutenant.6

Hood’s first assignment in the U.S. Army was in the rugged, untamed environs of northern California, where the young lieutenant of dragoons (cavalry) served at Fort Jones, established in October 1852 to protect miners and pioneer farmers from Indians. Lieutenant George Crook, one of Hood’s comrades who would later become a prominent Union general in the Civil War, described the post as nothing more than “a few log huts.”7

Hood’s primary duties consisted of commanding cavalry escorts for surveying parties into the rugged mountainous regions near the California-Oregon border. His final escort mission was in the summer of 1855 when he accompanied a party commanded by Lt. R. S. Williamson of the U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers exploring and surveying a railroad route from the Sacramento River Valley to the Columbia River. On August 4, Lt. Philip Sheridan, who would become the most famous Union cavalry leader of the Civil War, overtook the Williamson surveying expedition with orders to relieve Hood, who was instructed to return to northern California’s Fort Reading and then proceed east for a new assignment in Texas. “Lt. Hood started this morning with a small escort, on his return to Fort Reading, much to the regret of the whole party,” Williamson inscribed in his journal the next day.8

* * *

Hood was being transferred to a difficult and dangerous region. In September 1853, U.S. Secretary of War Jefferson Davis explained, “The duty of repressing hostilities among the Indian tribes, and of protecting frontier settlements from their depredations, is the most difficult one which the Army has now to perform; and nowhere has it been found more difficult than on the Western frontier of Texas.”9

Life for the immigrant settler on the southwestern frontier in mid-nineteenth century America was, for the most part, a perilous balance between opportunity and adventure; a high stakes all-or-nothing gamble in the face of extreme personal risk. An anxious mixture of prospect and uncertainty, estrangement from civilization, harsh weather, disease, and the rugged hardships of common existence took their toll on the various settlements. Of all the dangers encountered, none was more alarming than the ever-present threat of an Indian attack. For years, bands of warriors, primarily Comanche, terrorized the western settlements. The Plains Indians were expert horsemen and unmatched in the use of bow and lance, highly elusive, and difficult to predict. “No white person would risk settling far in the wilderness,” Texas governor James Henderson wrote in 1847, “if the United States troopers were not there to protect them.”10

The swift and certain response of the U.S. government came about in the form of a directive for the enlargement of the army, its arduous task being the defense and protection of the settlements scattered widely across the vast territory of the Texas frontier. The task was made at least slightly less onerous in 1855 when Secretary of War Davis authorized the formation and equipping of two new regiments of cavalry whose mission would be to suppress all hostile Indian activity on the Texas frontier. These units were to actively engage and aggressively pursue Indian raiding parties. One of these regiments was the elite 2nd Cavalry Regiment, to which Hood was assigned.

The majority of army officers (many of whom were veterans of the war with Mexico or recent graduates of West Point) were often bored and despondent with their dull routine or fading military career. As a result, many enthusiastically greeted the news of the formation of new cavalry regiments, an active assignment, and the possibility of long-overdue promotions. Among the fortunate few assigned to the new 2nd Cavalry Regiment were future Civil War notables Col. Albert Sidney Johnston, Lt. Col. Robert E. Lee, Majs. William J. Hardee and George H. Thomas, Capt. Earl Van Dorn, and Lt. John Bell Hood.

A year passed while Hood traveled east from his northern California duty station, spent time in Kentucky, and made his way to Jefferson Barracks in St. Louis, where the 2nd Cavalry Regiment was organized and outfitted. After reporting for duty to Lt. Col. Robert E. Lee in Texas in January 1857, Hood transferred to Fort Mason in Texas, then under command of Maj. George Thomas. On July 5 Hood led a 24-man cavalry expedition south from the fort on what would become an extremely long and hazardous search for a renegade Indian war party that would end in a sharp fight in the remote desolate area of the aptly named Devil’s River. Below is Bvt. Maj. Gen. Daniel Twigg’s cover letter to the assistant adjutant general of the army, together with Hood’s full report of the engagement.

* * *

1.1 Bvt. Maj. Genl. D. E. Twiggs to Lieut. Colonel L. Thomas

Head Quarters, Department of Texas

San Antonio, August 5th, 1857

Sir,

Lieut. Hood’s report was transmitted last mail, from subsequent information, not official. I think Lieut. Hood’s estimate of the Indian party was much too small. The same party it appears, attacked the California mail guard five days after, and near the place where Lieut. Hood had the fight, and they estimated the Indians to be over one hundred. Those officers were in the vicinity of Camp Mason, where Lieut. Fink of the 8th Infantry is stationed with a company of Infantry. If this company had have been furnished with some 15 or 20 horses, the second attack would not probably have been made. Lieut. Hood’s affair was a most gallant one, and much credit is due to both the officer and men.

I am, Sir, Very respectfully,

Your obt servant

(signed) D. E. Twiggs11

Bvt. Maj. Genl. U.S.A.

Comdg Dept.

Lieut. Colonel L. Thomas

Asst. Adjutant General

Hd. Qrs. of the Army

West Point N.Y.

Official copy for the information of Lieut. Hood, 2nd Cavalry,

respectfully furnished,

Jno. Withers

* * *

1.2 Lieutenant Hood’s Report of the Fight at Devil’s River, July 20, 1857

Fort Clark Texas

July 27th 1857

Sir,

I have the honor to submit the following detailed report of a scouting party, under my command, consisting of twenty four men of Company G 2nd Cavalry.

On the 5th July, I left Fort Mason to proceed to a point some fifteen miles west of Fort Terrett, and examine and explain a trail reported by Lieut Shoaff to be running West and South. I found no such trail. I then marched for the head of the South Concho, about half way between Fort Terrett and this point. I found a water hole which is a general camp for Indians passing from Fort Terrett to the head of the Concho. Avoiding the San Saba, I proceeded from the head of the mouth of the S. Concho, up the main Concho by Royal Creek, thence to its source, and from there to the mouth of [illegible] Creek, where I struck an Indian trail, about three days old, leading south, with some fifteen animals in the party. I followed it south, then east, then east to a water hole two miles south of the head of [illegible] Creek. I then followed them due south to water holes from thirty five to fifty miles apart (this line of water holes being their main route from the lower to the upper country) and on the morning of the 20th inst., which was my fourth day in their pursuit, I came to a water hole some seven miles above the head of Devil’s River, where a second party had joined them. Their camp showed that some thirty or forty had camped there.

I hurried on although my horses were very much wearied, and trailed over the bluffs and mountains, down the river, but some three miles from it. Late in the afternoon, from the extreme thirst of my men, I left the trail to go to the river and camp. About one mile from the trail I discovered some two miles and a half from me on a ridge some horses and a large white flag waving. I then crossed over to the ridge, without cover, supposin...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Documents

- Author’s Note

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Prologue

- Chapter 1: John Bell Hood: Son and Soldier

- Chapter 2: Dr. John T. Darby’s Medical Reports Concerning Hood’s Wounds Suffered at Gettysburg and Chickamauga

- Chapter 3: Hood’s Promotions

- Chapter 4: The Atlanta Campaign

- Chapter 5: The Cassville Controversies

- Chapter 6: Confederate War Strategy in the West After the Fall of Atlanta

- Chapter 7: Spring Hill, Franklin, Nashville

- Chapter 8: Army of Tennessee Troop Strength Calculations

- Chapter 9: The Wigfall Letters

- Chapter 10: John Bell to Anna Hood Letters

- Chapter 11: Miscellaneous Letters

- Chapter 12: Advance and Retreat: The Credibility of Hood’s Memoirs

- Chapter 13: The Hood Orphans

- Appendix: Laudanum, Legends, and Lore

- Bibliography