eBook - ePub

The Chickamauga Campaign: Glory or the Grave

The Breakthrough, Union Collapse, and the Retreat to Chattanooga, September 20–23, 1863

- 768 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Chickamauga Campaign: Glory or the Grave

The Breakthrough, Union Collapse, and the Retreat to Chattanooga, September 20–23, 1863

About this book

The second volume in a three-volume study of this overlooked and largely misunderstood campaign of the American Civil War.

According to soldier rumor, Chickamauga in Cherokee meant "River of Death." The name lived up to that grim sobriquet in September 1863 when the Union Army of the Cumberland and Confederate Army of Tennessee waged a sprawling bloody combat along the banks of West Chickamauga Creek. This installment of Powell's tour-de-force depicts the final day of battle, when the Confederate army attacked and broke through the Union lines, triggering a massive rout, an incredible defensive stand atop Snodgrass Hill, and a confused retreat and pursuit into Chattanooga. Powell presents all of this with clarity and precision by weaving nearly 2,000 primary accounts with his own cogent analysis. The result is a rich and deep portrait of the fighting and command relationships on a scale never before attempted or accomplished.

His upcoming third volume, Analysis of a Barren Victory, will conclude the set with careful insight into the fighting and its impact on the war, Powell's detailed research into the strengths and losses of the two armies, and an exhaustive bibliography.

Powell's magnum opus, complete with original maps, photos, and illustrations, is the culmination of many years of research and study, coupled with a complete understanding of the battlefield's complex terrain system. For any student of the Civil War in general, or the Western Theater in particular, Powell's trilogy is a must-read.

"Extremely readable, heavily researched, and mammoth in scope, Dave Powell's Chickamauga study will prove to be the most detailed treatment of the battle to date. Civil War buffs and historians alike will want these books on their bookshelves. where they will take their rightful place beside Tucker and Cozzens as seminal volumes on the battle." —Timothy B. Smith, author of Champion Hill and Corinth 1862

"[Powell's] latest monograph, The Chickamauga Campaign - Glory or the Grave . . . sets the standard for Civil War battle studies. . . . No one will ever look at Chickamauga the same way again." —Lee White, Park Ranger, Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park

According to soldier rumor, Chickamauga in Cherokee meant "River of Death." The name lived up to that grim sobriquet in September 1863 when the Union Army of the Cumberland and Confederate Army of Tennessee waged a sprawling bloody combat along the banks of West Chickamauga Creek. This installment of Powell's tour-de-force depicts the final day of battle, when the Confederate army attacked and broke through the Union lines, triggering a massive rout, an incredible defensive stand atop Snodgrass Hill, and a confused retreat and pursuit into Chattanooga. Powell presents all of this with clarity and precision by weaving nearly 2,000 primary accounts with his own cogent analysis. The result is a rich and deep portrait of the fighting and command relationships on a scale never before attempted or accomplished.

His upcoming third volume, Analysis of a Barren Victory, will conclude the set with careful insight into the fighting and its impact on the war, Powell's detailed research into the strengths and losses of the two armies, and an exhaustive bibliography.

Powell's magnum opus, complete with original maps, photos, and illustrations, is the culmination of many years of research and study, coupled with a complete understanding of the battlefield's complex terrain system. For any student of the Civil War in general, or the Western Theater in particular, Powell's trilogy is a must-read.

"Extremely readable, heavily researched, and mammoth in scope, Dave Powell's Chickamauga study will prove to be the most detailed treatment of the battle to date. Civil War buffs and historians alike will want these books on their bookshelves. where they will take their rightful place beside Tucker and Cozzens as seminal volumes on the battle." —Timothy B. Smith, author of Champion Hill and Corinth 1862

"[Powell's] latest monograph, The Chickamauga Campaign - Glory or the Grave . . . sets the standard for Civil War battle studies. . . . No one will ever look at Chickamauga the same way again." —Lee White, Park Ranger, Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Chickamauga Campaign: Glory or the Grave by David A. Powell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Histoire & Histoire de la guerre de Sécession. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter Three

Union Lines in Motion:

Sunday, September 20:

Dawn to 10:00 a.m.

Dawn to 10:00 a.m.

Charles Dana slept poorly. Unlike the vast majority of the tens of thousands of men bedded down in the surrounding woods and fields, he managed to make his bed indoors that night in the Widow Glenn’s cabin, as did a number of other officers from army headquarters. Huddled together with Capt. Horace Porter, recalled Dana, “we would go to sleep, and then the wind would come up so cold through the cracks [in the floor] that it would wake us up, and we would turn over together to keep warm.” Most of the staff managed a few hours rest, but for William Starke Rosecrans, none at all. Before dawn headquarters was stirring again.1

William D. Bickham, a reporter for the Cincinnati Commercial, was a longtime friend and observer of General Rosecrans. Also present that morning, Bickham observed Rosecrans in a rare moment of near-solitude. Watching, Bickham was struck with a flash of foreboding. Dressed in an overcoat, his trousers thrust into his boot-tops, and wearing “a light brown felt hat, of uncertain shape,” Rosecrans strode out of the little house to stand near Bickham and the campfire crackling in the yard. Neither man spoke. “An unlit cigar” was clamped in Rosecrans’s jaw. “I knew,” continued Bickham, “for I had seen Rosecrans often under widely different circumstances, that he was filled with apprehension for the issue of that day’s fight…. Rosecrans is usually brisk, nervous, powerful of presence, and to see him silent or absorbed in what looked like gloomy contemplation, filled me with an indefinable dread.”2

Corporal John K. Ely of the 88th Illinois was nearby and also observed his commander in this moment of frankness. “About sunrise Rossie [sic] and his staff came out of the house. Rossie[’s] countenance wore a heavy expression of care.” Ely added, loyally, “but he has a noble self relying look and if there is a General in our armies that can win a victory here Rossie is the one. He held an unlit cigar in his mouth and rode slowly away with it [still] unlit.”3

“We were all up early for various reasons,” wrote Col. John Sanderson, “one of which was that the night was intensely cold,” but also because “we expected an early attack.” Alexander McCook arrived to report that his troops “were moving,” but wanted advice on posting them. With the sharp overnight drop in temperature, fog now shrouded much of the battlefield. Contrary to everyone’s expectations, things remained strangely quiet. “About six, the General [Rosecrans] and the whole staff mounted … most … without having a mouthful to eat and drink,” and set out to survey the lines. Captain William Margedant of the Signal Corps recalled how still everything seemed. “General Garfield ordered the general staff officers to mount for the inspection of our lines. Major General Rosecrans led the cavalcade. It was one of those quiet, peaceful Sunday mornings enjoyed only in the country or the woods. There was no noise. [Even] speaking was done in a whisper.”4

About the same time as Rosecrans was ready to depart, a dispatch arrived from Maj. Gen. George Thomas of the XIV Corps, via the field telegraph connecting the two headquarters. “Since my return this morning,” wrote the burly Virginian, “I have found it necessary to concentrate my lines more.” Next, Thomas recapped his comments of the night before, uttered at Rosecrans’s council of war, asking for reinforcements. He reiterated that his left did not reach the Reed’s Bridge Road, and he needed more men. “I earnestly request that Negley’s division be placed on my left immediately.” With this repetition of the request for Negley, a second stone joined the slowly building avalanche.5

A lot had happened during the night. Two hours previous, Alexander McCook’s and Thomas Crittenden’s men began a quiet withdrawal from the Viniard Field line, completed successfully by first light. Brigadier General Tom Wood’s two brigades along with Sidney Barnes’s regiments all joined Horatio Van Cleve’s division west of the Dyer house to constitute Rosecrans’s designated reserve of five brigades. Captain T. J. Wright, commanding company H of the Union 8th Kentucky infantry, recalled that the redeployment was conducted “with such profound silence … that we on the skirmish line were not apprised of the move.” About 4:00 a.m., Wright learned that his brigade was gone, but the officer of the day had not yet ordered him back, and he dared not abandon the line. Wright expected to be attacked at first light, but instead, “about dawn, a heavy fog arose from the river … under cover of this, the rebel skirmish line withdrew, probably with the intention of being relieved. At this time General Sheridan … passed in the rear of our little company of forgotten pickets.” Catching the general’s attention, Wright secured permission to fall back. Irritated and snappish, Sheridan grumbled “that such gross neglect in a field officer of pickets should be looked into.”6

McCook commanded five brigades from his own XX Corps (Sheridan’s three and Jeff Davis’s two) as well as two more from Maj. Gen. James S. Negley’s division of the XIV Corps. Sheridan and Davis fell back “to the forks in the road in rear of the Widow Glenn’s house,” while Negley held his position at the west edge of Brotherton Field. Loose ends still had to be collected. Negley was short Brig. Gen. John Beatty’s brigade, which had stopped for the night at Osborne’s farm for water, and John T. Wilder’s men were now all alone in the Viniard Field area. A considerable gap now existed between Negley’s right and Wilder’s position. It was here that Rosecrans began the circuit of his lines.7

In Sheridan’s ranks, the 36th Illinois spotted their army commander as he rode by. The 36th was without rations and obtained breakfast only through the generosity of their fellow Illinoisans in the 88th. As they were eating, “Rosecrans came round, accompanied by his staff and escort. He looked in bad plight,” recalled regimental Chaplain William Haigh, “but his voice was ringing and cheery. ‘Boys,’ said he, ‘I never fight on Sundays, but if they begin it, we will end it.’” Rosecrans rode on.8

Having eaten, Sheridan’s division took up new positions. The regiments deployed in a line running south from the Glenn cabin, Col. Bernard Laiboldt’s and Brig. Gen. William Lytle’s men in line, with Col. Luther Bradley’s regiments (now led by Col. Nathan Walworth since Bradley’s wounding the evening previous) held in reserve. Behind them, also in reserve, were Davis’s two battered brigades, formed on the hill just west of the Dry Valley Road.9

The morning fog obscured much, but Rosecrans, ever the perfectionist, made minor tweaks and adjustments all along the lines as he rode. He and McCook had a brief discussion about the intended location of Davis’s division. McCook liked them on the hillside west of and overlooking the Dry Valley Road, from where they could repel and advance from either the south or east. That location might also keep them out of the worst of the fighting after their serious losses suffered the day before. Rosecrans disagreed. He thought that this put Davis too far to the west. The departmental commander wanted Davis’s men down into the valley and placed in close columns of division—a formation better suited for quick redeployment rather than fighting. Now McCook objected, and Rosecrans demurred, leaving the “exact place to be chosen” to McCook’s discretion. With that, McCook broke away to oversee his troops’ deployment.10

It was still very early, probably a few minutes before 6:00 a.m., when the headquarters party turned northeast. The sun was now rising, “red and sultry,” an effect of the ground mists and lingering smoke. To many, it seemed a bloody omen of things to come.11

Rosecrans next encountered Colonel Wilder, whom he passed on to McCook, “who would assign me to my position,” recalled Wilder. That detail attended to, the group rode quickly up the Glenn-Kelly Road, passing behind Maj. Gens. James Negley’s and Joseph Reynolds’s divisions in line at the Brotherton and Poe farmsteads, respectively. Somewhere along the way the army commander took note of Maj. Gen. Tom Crittenden’s XXI Corps, dimly visible to his left across the expanse of West Dyer Field, and situated too far to the south by Rosecrans’s reckoning. He dispatched revised instructions to the XXI Corps commander whose wording was destined to become the theme of the day: move “farther to the left.”12

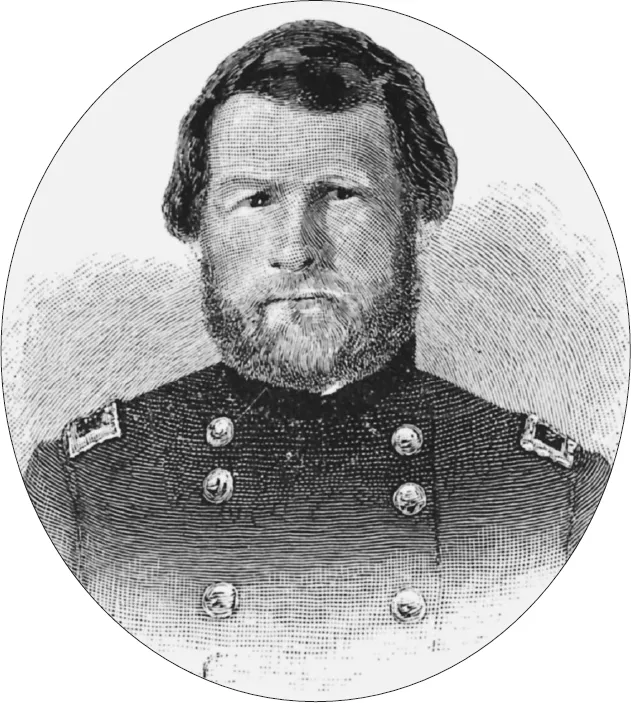

John M. Palmer led a division in the XXI Corps, but as he had the day before, he would spend September 20 attached to, and fighting with, George Thomas’s XIV Corps. Palmer’s troops would help anchor the new defensive line around Kelly Field. Battles and Leaders

Upon reaching Kelly Field, Rosecrans found Maj. Gen. John Palmer’s division, and another bustle of activity. Palmer awoke before dawn from his first sleep in 48 hours and one of the first things he did was hunt up George Thomas. He would be reporting to Thomas again that day, and wanted to know what was expected of him. “Pap” Thomas “pointed out to me the position to be occupied by Baird’s division … Johnson … moved and formed on Baird’s right; my own division …came next; then Reynolds, on my right…. The sun was up before our lines were formed.” As noted, next to Reynolds in line to the south was Negley, but that sector was currently McCook’s responsibility.13

Here, too, Rosecrans adjusted things more to his liking. Thinking that Palmer’s line needed to be more compact, he ordered that officer to close his line northward, moving Col. William Grose’s brigade out of the front line and into reserve. In turn, this move shifted Reynolds leftward. With only two brigades, Reynolds had no hope of covering the resultant gap, so Maj. Gen. John Brannan, whose division up to that point had been behind the lines in Dyer Field, moved Cols. John Croxton’s and John Connell’s brigades up to fill the space opened between Reynolds and Negley.14

Who ordered Brannan forward into the front line remains a mystery. No one took credit for the movement and Brannan failed to identify the source of the order, reporting only that “during the night I was ordered to put two brigades into line, connecting Reynolds’s and Negley’s divisions.” Brannan also noted that this redeployment was completed just before daylight, putting his recollection somewhat at odds with Palmer’s memoirs and Rosecrans’s own report. Rosecrans might have issued the order as part of his readjustments, but if so, leaving it out of his report would have been uncharacteristic for the notoriously meticulous army commander. A more likely candidate is Joseph Reynolds, who was senior to Brannan. Reynolds had taken overall responsibility for the Poe Field portion of the Union line the night before, which by the end of the action included Croxton’s brigade, and might well have assumed this informal arrangement remained in force. Reynolds later denied giving Brannan any specific orders, but he did converse with Brannan early that morning and later suggested Brannan deployed on his own initiative. According to Reynolds, Brannan told him “that he had been ordered to that vicinity, but had received no orders as yet to go into action at any specific place, and as no troops were on my right, he thought it incumbent on him to join his command on to my right.” Of critical importance, however, is that no one informed George Thomas of the new state of affairs, leaving Thomas to continue to think Brannan’s entire division was in reserve and available to call upon if needed.15

At the moment, Thomas’s attention was focused almost exclusively on what he felt to be the greatest vulnerability of his position: Brig. Gen. Absalom Baird’s inability to cover the entire distance north as far as the Reed’s Bridge Road some 800 yards north of Kelly Field. On September 19, when Brannan’s men moved south to help deal with the break in the Union lines around Brotherton Field and Baird’s division was shifted southward through the woods to support Palmer, Baird left his much-battered Regular Brigade under Brig. Gen. John King behind to guard this road. Rather than leave the Regulars there all alone, Baird during the night ordered them south to connect with the rest of his division. Once completed, King’s men managed what sleep they could until 3:00 a.m., when Baird roused all of his troops to start placing them in line at Thomas’s direction.

The key to George Thomas’s thinking was the long low ridge, much of it dominated by an open cedar glade, running parallel to and about one-half mile east of the La Fayette Road. This feature began at a point opposite Brotherton Field and ran north for roughly one mile until it tapered off just beyond the Reed’s Bridge Road. Thomas had spotted the ridge’s defensive potential on the 19th, and he intended to place his main line there. Unfortunately, south of Kelly Field the ridge was in Confederate hands, but beyond that the Federals made full use of the feature. By dawn, King’s Regulars were holding Thomas’s favored terrain where Alexander’s Bridge Road crested the slope. King’s ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Prologue

- Day Two: Saturday, September 19, 1863

- Day Three: Sunday, September 20, 1863