- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In the 1870s, to supplement their early steam engines, French warships were still rigged for sail. In the 1970s the Marine Nationale's ships at sea included aircraft carriers operating supersonic jets, and intercontinental ballistic missile submarines propelled by nuclear engines. Within this one hundred years, the Marine has played important roles in the acquisition of Asian and African colonial empires; until 1900 the lead role in a naval 'Cold War' against Great Britain; in 1904-1920 preparation, largely Mediterranean-based for, and participation in a Paris agenda in the First World War; a spectacular modernization unfortunately incomplete in the inter-war years; division, tragic self-destruction and a rebirth in the Second World War; important roles in the two major decolonization campaigns of Indochina and Algeria; and finally in the retention of major world power status with power-projection roles in the late 20th century, requiring a navy with both nuclear age and traditional amphibious operational capabilities. The enormous costs involved were to lead to reductions and a new naval relationship with Great Britain at the end of the 20th Century. These successive radical changes were set against political dispute, turmoil and in the years 1940 to 1942, violent division. Political leaders from the 19th Century imperialists to the Fifth Republic sought a lead role for France or if not, sufficient naval power to effectively influence allies and world affairs. Domestic economic difficulties more than once led to unwise 'navy on the cheap' policies and construction programs. The major post-1789 rift in French society appears occasionally among crews on board ships, in docks and builders yards, and in 1919-1920 open munities in ships at sea. In this work the author has tried to weave together these very varied strands into a history of a navy whose nation's priorities have more often been land frontier defense, the navy undervalued with a justifiable pride in its achievements poorly recognized. A study of the history of the Marine is also useful and important contribution to wider studies of French national history over thirteen tumultuous decades.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Three Republics One Navy by Anthony Clayton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction: France and Seapower

Throughout her modern history France has always considered herself as special among the world’s nations, with an important if not clearly defined historic and civilising role, a view summed up by Charles de Gaulle’s vision “France cannot be France without greatness”. This ideal required a diplomatic heavyweight role that called for a navy that could figure on the world stage, but what that naval power might mean was to vary very greatly under the Third and Fourth Republics, 1879 to 1945 and 1947 to 1958 respectively, and again in the first forty years of the Fifth Republic of 1958.1

The official title of France’s navy is La Marine, colloquially it is often referred to as ‘La Royale’, its headquarters ministry being in the Rue Royale in Paris. The Marine has a motto, inscribed prominently on board all French warships, ‘Honneur, Patrie, Valeur, Discipline’. It is a proud service with a history stretching back to the 17th Century, the time of its formation by Cardinal Richelieu in the reign of Louis XIII. Splendid periods of glory followed its expansion by the statesman Jean Baptiste Colbert in the reign of Louis XIV and in the last period of outstanding success before the Revolution in the reigns of Louis XV and Louis XVI. Linked to this tradition is pride in the achievements of explorers and navigators in the age of sail. The names of great privateers, sea officers and admirals are commemorated in successive generations of warships—Forbin, Jean Bart, Tourville, Duguay-Trouin, La Galissonnière, Suffren, along with explorer navigators such as Bougainville and Francis-Garnier.

One legacy of these traditions was for many years to be an institutional anti-British culture, a feeling that the wrong of Trafalgar must somehow be put right. This culture was much reduced by the mutual respect gained in the First World War. It was to reappear very strongly after the events of 1940, but then to diminish at first only slowly, but soon largely to disappear as the common interests of post-imperial France and Britain became increasingly evident. A second legacy from the history of France was a distrust of anything suggestive of divided loyalties or revolution, a consequence of 1789 when ships crews mutinied. Highly capable officers were murdered because they were aristocrats, discipline and training suffered. This legacy of the past also became evident in the years 1940 to 1943. The history and honour of the Marine, its ‘gloire’ (renown) remains never far from the minds of its commanding admirals.

A medium-sized country on a western end of the European peninsula, France could never hope to pursue a strategy of worldwide sea supremacy capable of either destroying or blockading any or all of opponents fleets whenever necessary. Moreover, in any case under the Third Republic the nation’s major strategic concern was a threat on border frontiers. But, equally France is a nation with ports on three important trading coastlines, two of which faced the long established opponent and rival, England. A national maritime strategy was a necessity. Argument ranged between the immediate needs for the defence of metropolitan coasts and ports against wider theories proposing effective local naval control over selected sea areas as a more effective way of advancing the nation’s interests. Forms of this control were to change over the decades, but in common throughout has been quests for an effective maritime strategy against a stronger naval power or coalition of powers. Specifically, then, French maritime strategy over the one hundred and thirty years covered in this work consisted of the traditional possessions of warships that could defend France’s coast (sometimes conveniently thought to be a provision that could be done by relatively cheap vessels), or when international relations underwent a major change, working with allied fleets. Across or in blue waters seapower could be used to acquire and later defend colonies, the behaviour of other powers could be influenced by the timely arrival of French power before the ships of others, the protection of movement on key transport routes such as those needed to convey troops from Africa to the metropole; a French presence in major allied sea or shore operations to ensure French interests were well served, perhaps even establishing favourable ground rules for a particular operation; and later in modern decades intelligence gathering by naval aircraft and patrol submarines or other forms of visible naval presence to support French diplomacy in matters ranging from arms control to fishing or undersea mineral extraction rights. The all-important assertion of world power status and a permanent United Nations Security Council seat was secured by the Fifth Republic by developing an intercontinental ballistic missile submarine force. In sum, French political leaders were not able to maintain a maritime strategy that met all aspirations but were nevertheless able to use seapower for the assertion of national interests very frequently, even if not always with complete success. The whole represents a constructive approach to a maritime strategy by a nation that had to put its navy second in national defence priorities. In one case, June 1940, for completely unforeseeable reasons, the possession of a fleet with powerful warships was to play a lead role at a time of national misfortune and crisis.

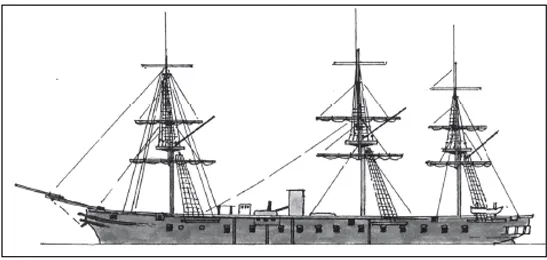

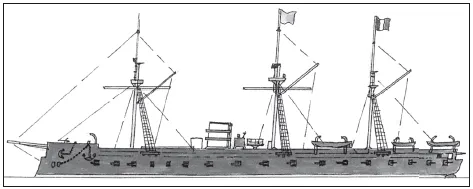

La Gloire, the world’s first armoured warship (1860), and in its day the pride of Napoleon III’s navy.

On the grand national stage, however, there has on occasions appeared a national fault-line. From 1789 to at least 1945 there has lain a massive rift in French society caused by the excesses and divisions within pre-Revolution France and the violence of the Revolution that ensued. The rift continued to be recriminatory and divisive, at times bitter, in the years that have followed factions on each side have found it difficult to work, sometimes even speak, with the other in political debate. After the final defeat of Napoleon I the country returned to an ordered establishment headed by a monarch of one House or another, property owners and an established church. Under the last and ablest of these monarchs, Napoleon III, the national economy underwent a major industrial revolution. Social divisions and opposition to authority had, however, erupted in 1830 and 1848, and with especial ferocity followed by equally ferocious repression in the Paris Commune uprising that had followed the defeat of Napoleon III in the Franco-Prussian war.

The end of the Second Empire plunged France into political chaos, worsened by the bitterness of defeat and the economic cost of a large indemnity payment. There followed seven years of political debate at times acrimonious. In the course of this it became clear that the people of France had regarded the candidates of the three rival royal houses, Bourbon, Orléans and Bonaparte as either totally unsuitable or simply sufficiently attractive enough, being too close to the Catholic Church. The Third Republic emerged—it was never to have a formal written constitution—after a series of votes culminating in in legislative elections in 1878 and the election of its first President in 1879. Although the first governments were essentially centre-right in political complexion the separate laws that had created the Republic’s institutions were to leave the balance of power between the Executive and the Legislature weighted in favour of the latter.

One very important consequence of this imbalance was to ensure that political divisions were often sharp, at times irreconcilable with governments short-lived. There were, for example, twenty-eight Ministers for the Marine between 1879 and 1914.2 Defence policy was on several occasions wasteful and contentious, and almost always funds were constrained. The political Left saw a professional army as a threat to the Republic, in the 1920s a street cry of “Kill a General” was to be heard. The Marine was less affected, being of interest to relatively few who criticised its costs and the high social standing of a number of its senior officers. But funding for ships and bases, even if specifically voted was not always actually forthcoming.

1 These Third Republic dates are those officially held by the French government. Others claim that the Third Republic came to an end when its laws were suspended by a vote of a sufficient number of members of both Houses of the Legislature on 11 July 1940, to which the official response is that the vote was under duress and therefore unconstitutional. It is relevant to note that the État Francais launched at the same time by Marshal Pétain was recognised internationally by foreign governments including the United States.

2 William Serman and Jean Paul Bertaud, Nouvelle Histoire Militaire de la France 1789-1919, Paris, Fayard, 1998, pp. 609-12 provides a table of names and dates and notes that between 1879 and 1898 of the majority number of ministers, eleven, all had served in the Marine Nationale, while between 1898 and 1914 only one serving naval officer was a minister. This political generation of ministers came from different professions, medicine, journalism and colonial administration. Their politics were Left or Left of Centre, many were freemasons. While there was no anti-clerical surveillance of officers compared to those that took place in the Army in 1902-04, the names of warships built at the end of the 19th and early 20th Century were an attempt to ‘republicanise’ naval culture.

2

Strategies and Ships: 1870s to 1904

The maritime strategy of the Third Republic in the years before the First World War falls into two very different phases.

From 1871 to the last decade of the 19th Century strategic thinking has been described by one French historian as a ‘Cold War’ against the traditional enemy Great Britain.1 Naval thought in this period believed that this must sooner or later end in full open warfare between the two nations. Although Emperor Napoleon III did not personally subscribe to this view his early 1860s navy was one of the finest in French history, leading the world in technology and superior to a neglected Royal Navy. Almost at the end of his reign a largely unexpected factor in naval strategy appeared with the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. Naval policy moved to the Mediterranean with Toulon as the major base. For ‘Cold War’ theorists a capability of closing the Canal to British merchants and warships was tempting and led to the quest for a Red Sea naval base. Paradoxically, though the trade and strategic common interests of Britain and France was to lead to joint French-British naval operations to ensure free movement through the Canal in 1881, 1915, 1939-40 and 1956.

By the end of the 1870s many French warships had been overtaken by technological developments and become obsolescent while the Royal Navy had returned to development. It was becoming clear that a major warship construction programme to match Great Britain was out of the question. Thinking and policy had therefore to be reviewed, and on both land and sea argued for the building up of colonial and naval force that would make France so close a second-ranking power after Great Britain and the Royal Navy that French interests would be secure, particularly in the Mediterranean. The colonial empire was to provide resources, additional military manpower and bases. These base ports were to constitute points d’appui, of strength from which blue water warships could set forth to harry British commercial shipping in a guerre de course war of attrition. For the defence of the Atlantic and Channel coasts much cheaper vessels, coast defence floating battery ships and light forces would suffice. The head of government, Jules Ferry, in his first 1880-81 and second 1883-85 administrations strongly supported the acquisition of colonies, though this policy was later to be the prime cause for his fall from power. The governments that followed him over the next fifteen years were only relatively less enthusiastic. Alliance with Russia, cemented with exchange naval visits, was seen as an important part of the containment of British expansions. A Russian naval visit to Toulon in 1893 provided a political ‘naval scare’ reaction in London. A group of naval theorists headed by Rear Admiral Aube, author of an important work, La Guerre Maritime et les Ports Français, and mostly composed of young officers, the Jeune École, envisaged an encircling chain of worldwide bases extending from Tunis, Obock (later Djibouti), Madagascar, Mayotte (Comoros), Saigon, a base in Tonkin, Nouméa, Tahiti, Tuamatu (Papua), the Panama Canal and Guadeloupe. By 1890 a rationalisation had proposed three major fortified bases, Martinique, Dakar and Saigon, with seven smaller and only lightly defended sally ports, Guadeloupe, Haiphong, Nouméa, Diego-Suarez, Port Phéton (Tahiti), Libreville and Obock.2 For the defence of the metropolis Dunkerque, Brest, Lorient and Toulon were to continue their traditional functions, Toulon benefiting from concern over Italian naval building. Anti-British feeling reached a crescendo at the time of the Fashoda crisis in 1898, with increased support for all the overseas bases. But already the growing military and naval threat of Imperial Germany was beginning to concentrate minds on the much more serious threat to the nation.

Warship construction was to reflect the changes in policy. The government that immediately followed the end of the Second Empire still aspired to follow the traditional naval policy of a fleet equal or superior to Britain’s Royal Navy based on a line of capital ships, called ‘First Rate Armoured Ships’ at the time. These capital ships were to be supported by ‘Second Rate Armoured Ships’ for coastal defence, by ‘armoured cruising ships’ and a number of sloops and gunboats. In 1872, before the drive for colonial expansion had come to dominate policy, the Minister for the Marine, Admiral Pothuau, set out a traditional and modernisation programme for the decade. This programme was almost immediately faced with the problems to bedevil French naval construction for the next hundred years, the ever-increasing costs of the technological advances needed for warships, inadequate access to iron and steel and, compared with Great Britain the small number of shipbuilding yards. Construction of major warships often took five or six years, sometimes even longer. Politically the public saw spending on the Army as the priority and the navy greatly reduced, some even arguing for its abolition. Pothuau’s options were limited.

Surveillante, 1870s Broadside Battleship.

The Marine 1879-80

The Marine’s line of capital battle ships that France could put to sea at the end of the 1870s was in consequence formed of obsolescent ships built in the years before or during the Franco-Prussian War, with the few more modern vessels completed in the following eight years, much but not all of the 1872 programme, forming a total of twenty-one (not including one purchased from the United States which proved to be valueless).

The ships were a very mixed collection.3 The earliest sixteen were old-fashioned broadside ironclads, the latter five were central battery vessels. The mix of construction patterns and different armaments created difficulties of maintenance and supply of the 1870s ships still in service, the oldest was Solferino completed in 1862, a sister ship had earlier been destroyed in a fire. These were designed by the pioneer of ironclad ships, Henri Dupuy de Lome, they displaced 6,700 tons and were built with a massive ram bow, to be a feature of French capital ships for the next twenty years, they were well armoured, equipped with ten 9.4-inch guns and could manage a top speed of 13 knots but still ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Author’s Note

- 1 Introduction: France and Seapower

- 2 Strategies and Ships: 1870s to 1904

- 3 Naval Operations 1871-1904

- 4 New Strategies and Preparation for War 1905-1914

- 5 The First World War and its Aftermath 1914-1920

- 6 The Inter-War Years 1919-1939

- 7 The Second World War 1939-1942

- 8 The Second World War 1943-1945

- 9 The Fourth Republic 1946-1958

- 10 The Fifth Republic 1958 to 1999

- Conclusion

- Appendix: Names of Marine warships that commemorate past commanders, sea officers and explorers

- Bibliography