- 329 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

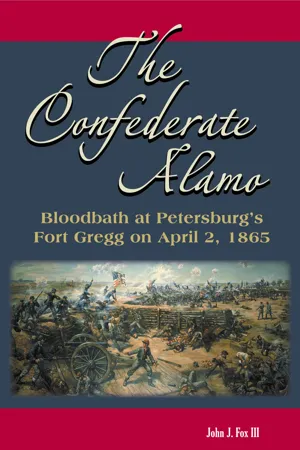

The first book-length study about the bloody, chaotic Battle of Fort Gregg: "Sweeping . . . insightful . . . military history at its best." —

Civil War News

By April 2, 1865, General Ulysses S. Grant's men had tightened their noose around the vital town of Petersburg, Virginia. Trapped on three sides with a river at their back, the soldiers from General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia had never faced such dire circumstances. To give Lee time to craft an escape, a small motley group of threadbare Southerners made a suicidal last stand at a place called Fort Gregg.

The venerable Union commander Major General John Gibbon called the struggle "one of the most desperate ever witnessed." At 1:00 p.m., hearts pounded in the chests of thousands of Union soldiers in Gibbon's 24th Corps. These courageous men fixed bayonets and charged across 800 yards of open ground into withering small arms and artillery fire. A handful of Confederates rammed cartridges into their guns and fired over Fort Gregg's muddy parapets at this tidal wave of fresh Federal troops. Short on ammunition and men but not on bravery, these Southerners wondered if their last stand would make a difference.

Many of the veterans who fought at this place considered it the nastiest fight of their war experience. Most could not shake the gruesome memories, yet when they passed on, the battle faded with them. On these pages, award-winning historian John Fox resurrects these forgotten stories, using numerous unpublished letters and diaries to take the reader from the Union battle lines all the way into Fort Gregg's smoking cauldron of hell. Fourteen Federal soldiers would later receive the Congressional Medal of Honor for their valor during this hand-to-hand melee, yet the few bloody Confederate survivors would experience an ignominious end to their war. This richly detailed account is filled with maps, photos, and new perspectives on the strategic effect this little-known battle really had on the war in Virginia.

By April 2, 1865, General Ulysses S. Grant's men had tightened their noose around the vital town of Petersburg, Virginia. Trapped on three sides with a river at their back, the soldiers from General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia had never faced such dire circumstances. To give Lee time to craft an escape, a small motley group of threadbare Southerners made a suicidal last stand at a place called Fort Gregg.

The venerable Union commander Major General John Gibbon called the struggle "one of the most desperate ever witnessed." At 1:00 p.m., hearts pounded in the chests of thousands of Union soldiers in Gibbon's 24th Corps. These courageous men fixed bayonets and charged across 800 yards of open ground into withering small arms and artillery fire. A handful of Confederates rammed cartridges into their guns and fired over Fort Gregg's muddy parapets at this tidal wave of fresh Federal troops. Short on ammunition and men but not on bravery, these Southerners wondered if their last stand would make a difference.

Many of the veterans who fought at this place considered it the nastiest fight of their war experience. Most could not shake the gruesome memories, yet when they passed on, the battle faded with them. On these pages, award-winning historian John Fox resurrects these forgotten stories, using numerous unpublished letters and diaries to take the reader from the Union battle lines all the way into Fort Gregg's smoking cauldron of hell. Fourteen Federal soldiers would later receive the Congressional Medal of Honor for their valor during this hand-to-hand melee, yet the few bloody Confederate survivors would experience an ignominious end to their war. This richly detailed account is filled with maps, photos, and new perspectives on the strategic effect this little-known battle really had on the war in Virginia.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Confederate Alamo by John J. Fox in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Grant Makes Plans to Bag Lee (Again)

MARCH 27 TO APRIL 1, 1865

“I was afraid, every morning, that I would awake from my sleep to hear that Lee had gone.”

WITH MARCH 1865’s BLUSTERY arrival and spring’s good weather near, General Robert E. Lee faced limited and difficult options. His beleaguered gray-clad soldiers struggled to man more than forty miles of defense line, which stretched from Richmond’s northeast side to its south, wrapping around Petersburg and continuing southwest beyond Hatcher’s Run. The sparse Confederate supply system had broken down, due in part to the Union Navy’s blockade of Southern ports. Four railroads intersected at Petersburg, from all points of the compass, but only two remained under Confederate control. Only one railroad—the South Side, which ran from Lynchburg to Burkeville—still provided an adequate supply line for Lee’s men.

The fifty-eight-year-old Southern commander could call on no more reserves to help man this extensive defense line, but his counterpart, Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, had thousands of reinforcements available. By March 1, 1865, some 56,000 gray troops in the Army of Northern Virginia faced more than 100,000 blue troops from the Army of the Potomac and the Army of the James. However, the Confederate numbers would continue to dwindle, due to casualties, desertions, and disease. The addition of Major General Philip Sheridan’s troopers from the Shenandoah Valley spelled potential doom for the Confederacy in Virginia. Additionally, Major General William T. Sherman’s army, fresh from its trek through Georgia and South Carolina, now stood in central North Carolina with another 80,000 Union troops at the ready. Sherman’s march had caused psychological and morale issues among Lee’s soldiers, many of whom feared for the safety of their families in those states. Earlier in the winter of 1864–1865, many of Lee’s men had deserted in order to protect their loved ones from the Yankees.1

The only Confederate force standing between a linkup of Sherman and the Union armies in Virginia was Lieutenant General Joseph Johnston’s threadbare Army of Tennessee, located at the time in central North Carolina. Lee understood that a connection of the Union armies spelled disaster for the South. He also realized that even without the arrival of Sherman, Grant’s troops could continue to exert pressure against the Richmond-Petersburg area, strangling his supply lines and starving his soldiers as well as the civilian populations of both cities. Lee had no prospect of disrupting the massive Union supply system. Ships laden with food, uniforms, weapons, and ammunition sailed up the James River to unload their cargo at the harbor of City Point, eight miles northeast of Petersburg. Union troops lacked nothing while their counterparts in gray lacked almost everything, except their courage and devotion to each other.

As early as February, the career military officer and astute tactician realized that his best chance to continue the war effort meant somehow extracting his army from behind the siege lines and moving to join with Johnston’s Army of Tennessee. He spent the month pondering how to complete this risky mission.

Eleven months before, in early 1864, Grant took over as commander of all Union forces. During the subsequent Overland Campaign, he had exhibited a tenacity to attack, unlike his predecessors. The cigar-chomping general had established his headquarters with Major General George Meade’s Army of the Potomac, and over a period of forty-five days this army had pushed and flanked Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia from the charred scrubs of the Wilderness all the way to the city limits of Petersburg.

Nicknamed the Cockade City, Petersburg was the second largest wartime city in Virginia at 18,266 residents in 1860. It lies twenty-three miles south of Richmond on the Appomattox River’s south bank. By mid-June 1864, Grant’s veterans attacked the eastern side of Petersburg only to be slowed by a small but determined group commanded by General Pierre G. T. Beauregard. Beauregard’s troops provided time for Lee’s veterans to rush to Petersburg and dig formidable defense lines. Union troops began to dig similar entrenchments parallel to the Confederate works in the advent of trench warfare. Soldiers from both sides endured miserable conditions, which caused one Union general to lament, “This war of rifle pits is terrible.”2

By 1865, the survival of the Confederate capital depended on Petersburg. Grant realized that Petersburg’s position as a transportation and manufacturing center provided much of the supplies that sustained Richmond, and he believed that if Petersburg fell, Richmond would fall also. As Lee feared for his soldiers and cause, the fog of war also created problems for Grant, who later described his worries:

One of the most anxious periods of my experience during the rebellion was the last few weeks before Petersburg. I felt that the situation of the Confederate army was such that they would try to make an escape at the earliest possible moment, and I was afraid, every morning, that I would awake from my sleep to hear that Lee had gone, and that nothing was left but a picket-line. He had his railroad by the way of Danville south, and I was afraid that he was running off his men and all stores and ordnance except such as it would be necessary to carry with him for his immediate defense. I knew he could move much more lightly and more rapidly than I, and that, if he got the start, he would leave me behind, so that we would have the same army to fight again farther south–and the war might be prolonged another year.3

Not wanting to allow Lee to slip away, Grant needed the weather to improve so that he could launch a spring campaign. Grant insisted, “I could not see how it was possible for the Confederates to hold out much longer where they were.” He believed that he could end the war in the east once dry weather arrived. He expressed two concerns before he felt comfortable moving his men. First, “the winter had been one of heavy rains, and the roads were impassable for artillery and teams.” His second issue involved cavalry: “General Sheridan, with the cavalry of the Army of the Potomac, was operating on the north side of the James River, having come down from the Shenandoah [Valley]. It was necessary that I should have his cavalry with me, and I was therefore obliged to wait until he could join me south of the James River.” Early in the last week of March, Sheridan’s cavalry arrived, and the weather improved somewhat.4

On Monday, March 27, the major Union players in the Eastern Theater converged on the Petersburg area. Grant met with President Abraham Lincoln, Generals Sheridan and Sherman, and Admiral David Porter. The Union council of war made its decisions, and Grant issued orders to place his great war machine in motion. That night, three infantry divisions and one small cavalry division from Major General Edward O. C. Ord’s Army of the James, which had been stationed north of the James River, moved toward the Cockade City. The men of Major General Alexander A. Humphreys’ Second Corps and Major General Governour K. Warren’s Fifth Corps, located on the Union left flank southwest of Petersburg, readied their equipment to cross Hatcher’s Run and extend the lines toward Dinwiddie Court House. As they moved left, Ord’s troops would replace Humphreys’ men in the trenches. Two of Ord’s divisions came from Major General John Gibbon’s Twenty-fourth Corps. The objective, as reiterated by Grant, was “to get into a position from which we could strike the South Side railroad and ultimately the [Richmond and] Danville railroad.”5

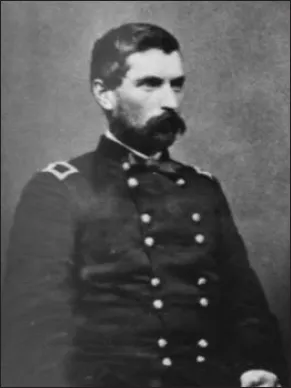

Major General John Gibbon—Union Twenty-fourth Corps commander. Gibbon was born in 1827 and he graduated from West Point in 1847. He commanded the famous Iron Brigade and received wounds at Fredericksburg and Gettysburg. Gibbon’s two brothers served on the staff of the 28th North Carolina. MOLLUS Collection, U.S. Army Military History Institute, Carlisle, Pa.

Repositioning John Gibbon’s corps to Petersburg would represent a huge danger to Lee’s army. Gibbon’s men crossed two rivers and marched for nearly forty miles along the periphery of the Richmond-Petersburg lines, but Lee would not learn of this move in a timely way. For if he had, he certainly would have issued orders earlier for more of Lieutenant General James Longstreet’s battle-toughened soldiers to move from the Richmond area toward Petersburg—before it was too late.6

Around 4 PM on March 27, orders passed through the camp of the 11th Maine to “strike tents and pack up for the Spring campaign.” A sense of excitement permeated the atmosphere that afternoon as the men ran to and fro rolling up, folding, and stowing their clothing and equipment. A short time later, the Mainers fell into formation. As one soldier later recalled, they carried “everything we possess[ed] strapped on our backs.” Their knapsacks bulged with the essentials: sixty rounds of cartridges, rations for four days, extra clothing, a poncho, and eating utensils. The sun dipped below the trees to the west, casting long shadows over the rows of men. The order rang out, “Right shoulder shift arms!” Hundreds of rifles moved, and the cool evening air carried the click of wood and metal. The regiment marched out and took its position in the Third Brigade column, sandwiched between sister regiments. Brigadier General Robert S. Foster rode at the head of his First Division as the Twenty-fourth Corps moved southeast, away from Richmond and toward the James River crossing at Deep Bottom, five miles distant.7

As the sky grew dark, the men bumped into each other and stumbled along, reaching Deep Bottom after four hours. They stepped onto the wobbly pontoon bridge and shuffled across the quarter-mile inky black ribbon of water. The weary troops continued marching another seven miles across the Bermuda Hundred peninsula, an area formed by the confluence of the James and Appomattox rivers.

Captain Albert Maxfield, 11th Maine, described the difficult forced march:

The night was a dark one, with rain. The soft roads, cut up by artillery wheels and wagon trains, stretched here and there into wide morasses of knee-deep mire, into which we could plunge unexpectedly, to wallow through as best we could. It led through woods, and in the darkness those deviating from the road ran against trees; and curiously enough, while the men would wade and flounder along the road in grim silence, when they found themselves violently opposed by a tree-trunk they would use language both lurid and rhetorical.8

A crack of light finally appeared along the horizon, off to the left of the column, as they approached the Appomattox River at Point of Rocks. The squeak and clatter of artillery caissons drowned out the shuffle of thousands of feet as the big guns rolled over the bridge.9

The growing daylight gleamed upon heart-shaped badges worn on the men’s jacket breasts or caps. On March 18, the Twenty-fourth Corps had adopted the heart as the corps’ badge. Traditionally the three divisions in a corps assumed the colors of red, white, and blue in numerical order. Thus, the First Division troops pinned red hearts to their uniforms; the Second or Independent Division pinned on white hearts, and the Third Division wore blue hearts.10

As Maxfield’s men neared Petersburg, they came under the scrutiny of new eyes. He was glad the regiment, “although leg weary and heavy eyed, presented a soldiery appearance to the curious onlookers of the Army of the Potomac, that from daylight on watched the march of the troops of the Army of the James.” He knew what kept his men moving forward: “hot coffee, daylight, and the pride that led us to put the best foot foremost under the eyes of our critical, if unsympathizing, friends of the Army of the Potomac.”11

Grumbles rolled along the ranks as the serpentine column continued, and most men wondered where they were going and when they would stop. Thousands of tired, overloaded infantryman abandoned equipment along the sides of the road. One Pennsylvania soldier had urged his sister not to send him anything, “because the less a soldier has to carry the better for him.” This soldier, the 199th Pennsylvania’s Joseph Cornett, lamented the “team load” of discarded items along the march route: “I did not throw away one article that I started with, but if we march again I will leave at least half my load behind. It is surprising to see what is lost or wasted by soldiers just breaking camp in the spring.”12

Large groups of horsemen would clop by these infantrymen and their cast-off supplies, making many of the tired walkers even more frustrated with their lot. Through breaks in the woods they could see other columns of cavalrymen—Sheridan’s troopers—moving in the same southwesterly direction.

The 11th Maine’s Private William H. Wharff expressed his misery: “We hope to halt soon as we are getting tired and our knapsacks are growing heavy.” He added, “We seem to be marching for something as we are only allowed to stop long enough to devour a hard-tack and then it is ‘Fall in’ and on we go, ‘tramp, tramp.’” Similarly, Cornett complained that officers allowed the column to halt only every two to three hours for about fifteen minutes. A brief stop early on March 28 allowed him just enough time “to cook our coffee.” The men in Cornett’s First Brigade relished their one-hour stop at noon, while Wharff bragged that the men in his Third Brigade halted for longer at about 1 pm. Many of the Twenty-fourth Corps soldiers probably would have agreed with Cornett when he wrote, “I never experienced such a hard march in my life.”13

When Wharff’s brigade column halted at about 9 pm, March 28, the temperature hovered around 50 degrees. Many of the tired men were soon fast asleep, “having marched 27 hours without sleep and scarcely any rest.” Despite the exhausting march of the previous day, the men rose long before dawn on March 29 and began marching again around 4 AM. The lead units of the First Division reached Hatcher’s Run, seven miles southwest of Petersburg, at 8 AM. In this part of the woods, they saw the entrenchments and quarters of the Army of the Potomac’s Second Corps. As the trees stood sentinel, the Second Corps soldiers moved westward from their position to help extend Grant’s lines. The soldiers in Major General John Gibbon’s Twenty-fourth Corps quickly realized this just-abandoned hole in this part of the line was now theirs to fill.14

Gibbon may have felt a sense of déjà vu as he coordinated the arrival of his new corps; he had temporarily commanded the Second Corps several months before. The hard-fighting and multi-wounded major general had been born in Philadelphia on April 20, 1827, and ...

Table of contents

- Coverpage

- Titlepage

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Also by John J. Fox, III

- Contents

- Maps

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1. Grant Makes Plans to Bag Lee (Again)

- 2. Lee Faces a Serious Disaster

- 3. The Union Breakthrough

- 4. Confederate Third Corps Chaos

- 5. Confederates Punch Back

- 6. Reality Reaches Richmond

- 7. Gibbon’s Twenty-fourth Corps Approaches Fort Gregg

- 8. Walker’s Unusual Artillery Order

- 9. The Fort Gregg Defenders: An Uneasy Resolve

- 10. A Long Wait to Attack

- 11. Osborn’s East Wing Attacks in First Wave

- 12. Dandy’s West Wing Attacks in First Wave

- 13. The Confederate Defenders Steel Themselves for the Blue Wave

- 14. Low on Ammunition and No Reinforcements

- 15. Union Reinforcements Hit the West Wall

- 16. Another Union Division Attacks

- 17. The Blue Wave Surges over the Walls

- 18. Inside the Pit of Fort Gregg

- 19. Fort Whitworth

- 20. Did Sacrificing the Twin Forts Allow Lee to Escape?

- Epilogue

- Appendix A: The Fort Gregg Area Today

- Appendix B: Order of Battle

- Appendix C: Fort Gregg Casualties

- Appendix D: Confederates at Fort Gregg

- Appendix E: Fort Whitworth’s Controversial Artillery Withdrawal

- Appendix F: The First Union Flag on Fort Gregg Controversy

- Appendix G: Which Southern Artillery Batteries Helped Defend Fort Gregg?

- Appendix H: Fort Gregg Medal of Honor Recipients

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author