![]()

Part I

ENEMY AT THE GATES

In the trenches at Petersburg: Digging parallels (trenches) near the front. William Waud

![]()

Chapter 3

“Hold on at all hazards!”

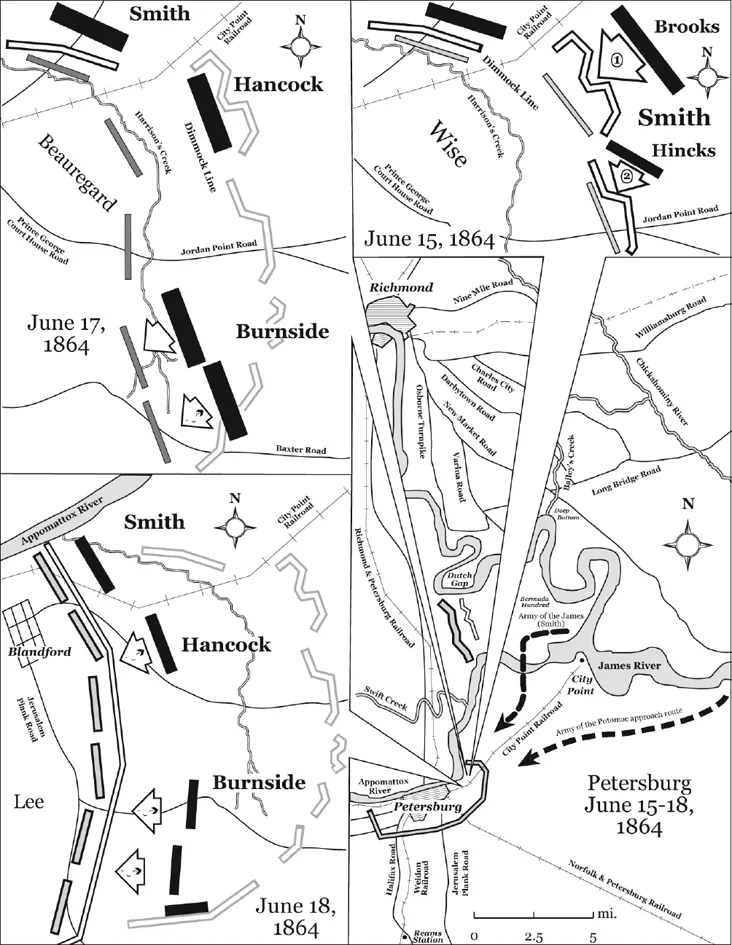

June 15 - 18, 1864

Ulysses S. Grant

Final Report of Operations, March 1864-May 1865

The movement in the Kanawha and Shenandoah Valleys, under General [Franz] Siegel, commenced on the 1st of May… . General Siegel moved up the Shenandoah Valley, met the enemy at New Market on the 15th, and after a severe engagement was defeated with heavy loss… . Major-General [David] Hunter was appointed to supersede him… .

General Hunter immediately took up the offensive, and moving up the Shenandoah Valley, met the enemy on the 5th of June at Piedmont, and … defeated him. … To meet this movement under General Hunter, General Lee sent a force, perhaps equal to a corps, a part of which reached Lynchburg a short time before Hunter. After some skirmishing on the 17th and 18th, General Hunter, owing to a want of ammunition to give battle, retired from the place. Unfortunately, this want of ammunition left him no choice of route for his return but by way of Kanawha. This lost to us the use of his troops for several weeks from the defense of the North… .

To return to the Army of the Potomac …

Wednesday, June 15

Ulysses S. Grant

The troops no longer cheered him. He had never asked for, or encouraged, their cheers, but they had cheered him anyway. They cheered him after the terrible combat in the Wilderness ended, when his orders were for the army to advance and not retreat. They cheered him at Spotsylvania, despite days of dangerous trench warfare—a cycle broken only by furious assaults that stacked up the dead and wounded on both sides. They cheered him after North Anna, when he led them away from the enemy’s formidable earthworks without attacking. But the cheers ended at Cold Harbor.

There was something about the ground there that had made the Confederate trenches seem less dangerous, so Grant insisted upon an all-out assault. On the morning of June 3, some 60,000 blue-coated soldiers charged into a killing ground. Perhaps 7,000 of the Yankees were shot down in the first thirty minutes at Cold Harbor. “Many soldiers expressed freely their scorn of Grant’s alleged generalship,” John Haley, a Maine soldier, noted in his journal.

That night Grant had confessed his failure to his staff. “I regret this assault more than any one I have ever ordered,” he told them. (Afterward, one of his aides observed, the “matter was seldom referred to again in conversation.”)

Cold Harbor had been Grant’s battle – Meade had seen to that. Two days after it was over, the temperamental commander of the Army of the Potomac confided to an officer that he was fed up with Grant’s getting all the credit. Meade, recalled the officer, complained that “he had worked out every plan for every move from the crossing of the Rapidan onward, that the papers were full of the doings of Grant’s army, and that he was tired of it, and was determined to let General Grant plan his own battles.”

It had taken Grant two days of reflection to chart a new course. Retreat of any kind was not considered. “I shall take no backward steps,” he had vowed in mid-May, and he meant it. From the Wilderness to Spotsylvania to North Anna to Cold Harbor, Grant’s purpose had been the same: to maneuver Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia away from their entrenchments, and to defeat them in a stand- up, open-field fight. That had never happened, however, and Grant now decided to end this deadly dance of death with Lee by striking out for Petersburg.

This time, though, Grant would not pull all the strings. He would issue the orders, but the Army of the Potomac, directed by George Gordon Meade, would carry out these directives.

It was midday, when Grant—having transferred to a steam launch after crossing the James – established headquarters at City Point. Major General William F. “Baldy” Smith, along with 16,000 men from Butler’s Army of the James, was attacking the Cockade City a few miles to the southwest. “I believed then,” Grant reflected years afterward, “and still believe, that Petersburg could have been easily captured at that time.”

William F. “Baldy” Smith

War offered little mystery to “Baldy” Smith. It was nothing more than a science, and he, in the opinion of many (including himself), was a master scientist.

The curse of Smith’s career was the succession of mediocrities he had been forced to serve. He had hungered for an independent command and looked to Grant to provide it. Grant’s promotion to direct all the Union armies had come after he broke the Confederate siege of Chattanooga, an operation in which Smith had played an important part. But when orders arrived in April, Smith discovered that he was to be merely a corps commander in Major General Benjamin F. Butler’s Army of the James, soon to begin operations against Richmond.

To say that Smith, who had graduated fourth in the West Point class of 1845, despised the crafty, politically powerful Butler would be an understatement. Smith had Grant’s ear, and he promptly filled it, saying, “I want to ask you how you can place a man in command of the two army corps, who is as helpless as a child on the field of battle, and as visionary as an opium eater in council?” (“General Smith,” Grant later commented in a letter to Henry Halleck, “whilst a very able officer, is obstinate, and likely to condemn whatever is not suggested by himself.”)

Butler’s campaign against Richmond’s southern defenses had been everything Smith had predicted: badly coordinated, poorly conducted, and devoid of substantial results. It mattered not to Smith’s way of thinking that as the officer in charge of half of Butler’s army, he somehow shared in the blame.

Smith and 12,000 soldiers from the Army of the James had joined the Army of the Potomac in late May at Cold Harbor, just in time to take part in the fighting. Smith found little to like in the way George Meade ran things. Fouled-up orders on June 1 resulted in his men’s marching miles in the wrong direction when they were desperately needed at Cold Harbor, and Smith was appalled when he learned what the attack “plan” was for June 3. In his opinion, it “was simply an order to slaughter his best troops.” Commanded by Meade to renew the June 3 assault after its bloody repulse, “Baldy” Smith refused point blank. When new orders came on June 11, instructing him to return to Bermuda Hundred, Smith was not sorry to leave. (“Meade is as malignant as he is jealous & as mad as he is either,” Smith had groused to a confidant in early April.)

On June 14, Smith and his men had barely returned by means of river transports to Butler’s domain when the opportunity he had been seeking presented itself. As Smith recalled, “I arrived at Bermuda Hundred with my aid[e]s about sunset, and was told … that I was to proceed at two o’clock a.m. to attack Petersburg.”

This time there would be no Ben Butler or George Meade to interfere. This time it would be “Baldy” Smith’s show.

P. G. T. Beauregard

Glory had passed through the fingers of Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard like fine jeweler’s sand. His was a life meant for glory, and he had wandered the Confederacy in search of it. The Creole officer had directed the bombardment of Fort Sumter, and there he began his addiction to fame. Then he was called to Richmond and given command of the Confederate forces near Manassas, Virginia, where he was forced to share the spotlight with another ambitious officer, Joseph E. Johnston.

Manassas had been a great Southern victory, but carping politicians had seen to it that the glory was spread among the senior officers present. Vain and outspoken, Beauregard openly vented his feelings, and in reward was transferred to the West, about as far from Richmond as it was possible to get. Once more Beauregard shared the stage with one of the Confederacy’s heroes, this time Albert Sidney Johnston. The two led their barely trained army into the combat holocaust of Shiloh, where nearly 20,000 men of both sides fell in two terrible days. Johnston was killed at the height of the Confederate success; it fell to Beauregard to withdraw the army after Johnston’s badly flawed battle plan unraveled.

Acrimonious bickering with subordinates and superiors had marred the next months, and Beauregard had been reassigned to the scene of his unsullied triumph, Charleston. Under his inspired leadership, a major Federal offensive against the city in April 1863 was turned back. Once again his greatness had been made clear. Beauregard now expected to be given command of one of the Confederacy’s two major armies.

The orders Beauregard did receive from Jefferson Davis, no friend of his, were almost insulting: he was to take charge of the military department covering North Carolina and Virginia south of the James River. Everyone knew that the decisive actions would take place north of Richmond, not south of it. Even worse, he would again have to share the limelight with a hero of the Confederacy, in this instance Robert E. Lee, an officer whom Beauregard later assessed as having little “Mil[i]t[ar]y foresight or pre-science or great powers of deduction.”

Even as Lee’s men were grappling with Grant’s in the Wilderness on May 5, Ben Butler’s Army of the James had landed at Bermuda Hundred, smack between Richmond and Petersburg and within a cannon shot of the vital rail line that supplied both the Confederate capital and the Army of Northern Virginia. For the first few days of this crisis Beauregard remained in North Carolina, gathering men and material to send north to the fighting. He finally arrived in Petersburg to take personal command on May 10.

The next thirty-six days had been a flurry of frantic maneuvering, furious combat, and petty squabbling as the Creole officer moved men from threatened point to threatened point. Instead of being given the reinforcements he needed, Beauregard was pressured by Richmond to release troops to reinforce Lee, who had taken serious losses during his continuous engagement with Grant’s army. Time and again Beauregard used red tape to delay the transfers, but once Butler had been effectively bottled up in Bermuda Hundred, it became much easier for Lee to argue that Beauregard needed fewer men to hold his entrenched line. President Davis agreed, and on May 30 Beauregard grudgingly sent Lee one of his largest veteran units, Major General Robert Hoke’s division.

In the stalemate following the June 3 Federal debacle at Cold Harbor, Beauregard had foreseen with startling clarity that he would be the next target. The mishandled June 9 thrust at Petersburg served only to heighten his anxiety, and the telegraph wires to Richmond buzzed with his appeals for more troops. Then Grant’s entire army literally disappeared from Lee’s front, and the Virginian seemed uncertain of its destination. Soon afterward, the Federal units that had been detached from Butler’s Army of the James (“Baldy” Smith’s command) rejoined it. Lee may have wondered what Grant was going to do, but Beauregard had no doubts. At 7:00 a.m. on the morning of June 15, he wired Richmond:

RETURN OF BUTLER’S FORCES SENT TO GRANT … RENDERS MY POSITION MORE CRITICAL THAN EVER; IF NOT RE-ENFORCED IMMEDIATELY ENEMY COULD FORCE MY LINES AT BERMUDA HUNDRED … OR TAKE PETERSBURG… . CAN ANYTHING BE DONE IN THE MATTER?

George Gordon Meade

George Meade wanted his army back.

He should have anticipated that Grant would take the Army of the Potomac from him. John Gibbon, a Second Corps division commander, understood the problem: “Gen. Meade occupied a peculiar position at the head of the army. He was a commander directly under a commander, a position at best and under the most favorable circumstances, not a very satisfactory one to fill… . [Though] all the details of projected operations are left to the army commander he cannot help but feel that they are under the immediate supervision of another and he must necessarily be shackled and sensible of the fact that he is deprived of that independence and untrammeled authority so necessary to every army commander.” Another aide stated the situation even more bluntly with a slip of the pen, heading one set of reports “The Army of the Potomac, commanded by Lieut. Gen. U. S. Grant in person, Major-General Meade second in command.”

Second in command. How it stuck in his throat, like a clod of Virginia dirt! Meade remembered how cocksure Grant had been when he came east to face Bobby Lee. The forty bloody days of the Overland Campaign had ended that. “I think Grant has had his eyes opened, and is willing to admit now that Virginia and Lee’s army is not Tennessee and [Braxton] Bragg’s army,” Meade reflected after Cold Harbor. At about the same time, he reacted to an editorial in the Army Magazine praising Grant’s military genius: “Now to tell the truth, the latter has greatly disappointed me, and since this campaign I really begin to think I am something of a general.”

Today Grant had gone on ahead, leaving Meade to oversee the Army of the Potomac’s crossing of the James. For the moment, he was alone with his army and able to lose himself in small details. He was still uncertain as to what Grant intended to do with the army once it crossed over, but, he thought with a touch of irritation, Grant would let him know soon enough.

Winfield Scott Hancock

He was a facade—a weary, hurting man trapped within the image of a fearless warrior. He was Hancock the Superb, Hancock the hero of Gettysburg, Hancock the valiant fighter. As U. S. Grant put it, “Hancock is a glorious soldier.”

Or had been a glorious soldier. The Overland Campaign finished what a Confederate bullet at Gettysburg had begun. It smothered the fires of ambition and reckless courage that had launched his star on its ascent.

For the past forty days, wherever there had been a tight spot or a need for a decisive stroke, there had been Hancock and his Second Corps. For two terrible days of fighting in the Wilderness, he commanded more than half of Meade’s army. Next came Spotsylvania, where Hancock and his men had tense engagements at Todd’s Tavern and the Po River and then were engulfed in the nightmare of the Bloody Angle. When Grant decided after Spotsylvania to dangle a corps before Lee as bait, he chose Hancock’s Second Corps. After that was North Anna, where, for one heart-stopping afternoon, Hancock and his men were trapped with the river at their backs and Lee’s entire army in their front. Unknown to them, Lee had suddenly became too ill to direct the crushing blow, allowing the desperate Federals enough time to entrench and protect themselves. No one could have imagined that things could get worse, but then came Cold Harbor, where Hancock’s weary foot cavalry delivered the heaviest assault in that futile action. When someone at Cold Harbor asked Hancock where the Second Corps was, he replied, “It lies buried between the Rapidan and the James.”

Hancock was in physical as well as mental distress. That unhealed Gettysburg wound in his groin could be agonizingly painful at times, and his strenuous exertions during the recent campaign had not helped matters. The constant discomfort was like a drug that clouded his thinking and dulled his perceptions.

Fortunately, Hancock’s present orders required little analysis. His Second Corps was the first to cross the James River, using a flotilla of Navy ships, river transports, and even some New York...