![]()

Chapter 1

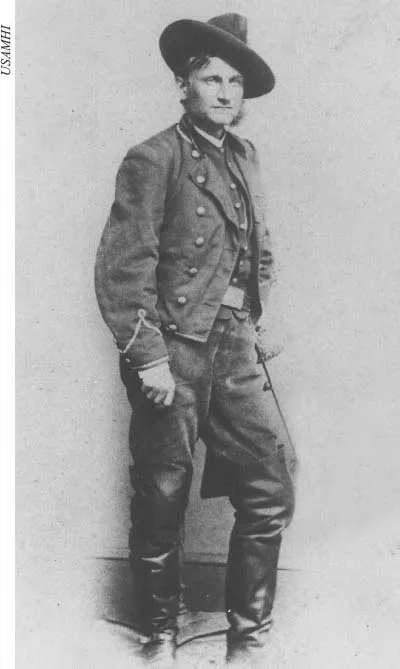

Hugh Judson Kilpatrick and his Federal Dragoons

WHEN Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman led his armies into the field in the spring of 1864, he took with him a new set of cavalry commanders. These two senior officers, Maj. Gen. George Stoneman and Brig. Gen. Hugh Judson Kilpatrick, had both served with the Army of the Potomac with mixed results, and had both come west looking for opportunities to distinguish themselves.

Because Stoneman was the ranking general officer in the Federal cavalry in the spring of 1864, he became Sherman’s chief of cavalry by default. That summer and with Sherman’s blessing to continue Stoneman led a raid toward Macon and on to Andersonville prison, where the cavalryman intended to liberate Union prisoners of war. The raid ended in disaster short of Macon on July 29 when Stoneman and 700 of his troopers were captured and the raid fell apart. Command of Sherman’s horsemen fell to Kilpatrick, the next senior general officer. Thanks to Sherman’s energetic intercession, Stoneman was exchanged that autumn and given command of the district that included Eastern Tennessee, but he would never again serve in the field with Sherman.1

Judson Kilpatrick had come West under uncertain circumstances. He had fought bravely—if not always wisely—in the Eastern Theater and relieved of command as a result. A cloud hung over Kilpatrick’s head, one he very much wanted to dissolve.

Hugh Judson Kilpatrick was born in Deckertown, New Jersey, on January 14, 1836, the second son of Simon and Julia Kilpatrick. The elder Kilpatrick was a colonel in the New Jersey state militia who cut an imposing figure in his fine uniform. This image was not lost on little Judson, who at an early age decided he wanted to be a soldier. He spent his childhood attending good schools and reading about military history, eagerly learning all he could about great captains and campaigns.2

The boy’s most earnest dreams came true in 1856 when he received an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point. He graduated from in the Class of 1861, seventeenth in a class of forty-five. “His ambition was simply boundless,” recalled a fellow cadet, “and from his intimates he did not disguise his faith that…he would become governor of New Jersey, and ultimately president of the United States.”3 A few days after graduating, Judson married his sweetheart Alice Shailer, the niece of a prominent New York politician. He would carry a personal battle flag emblazoned with her name into combat throughout the upcoming war, which would last longer than his marriage to Alice. The young lieutenant and his bride spent only one night together before he rushed off to begin his military career.4

A dominant personality trait emerged early in Kilpatrick’s career: intense ambition. Recognizing that volunteer service would lead to quicker promotions than the Regular Army, the new graduate asked his mathematics professor from West Point, Gouverneur K. Warren, to recommend him for a captaincy in the newly-formed 5th New York Infantry. On May 9, 1861, Kilpatrick received a commission as captain of Company H, 5th New York. One month later he fought at Big Bethel on June 10 in the Civil War’s first full-scale confrontation. The young captain was wounded in the skirmish and earned the distinction of being the first West Pointer on the Union side injured by enemy fire. For someone looking forward to a political career, Kilpatrick was off to a good start.

When he returned to duty he did so as lieutenant colonel of the 2nd New York (Harris) Cavalry. His parting from the 5th New York was not graceful. Kilpatrick had taken sick leave rather than return to duty with his regiment, all the while angling for higher rank in a cavalry regiment while angering Warren in the process. As the second in command of a regiment of horsemen, Kilpatrick served in Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac. He took part in the 1862 Peninsula Campaign. That summer his regiment left the Virginia Peninsula to serve with Maj. Gen. John Pope’s new Army of Virginia. The lieutenant colonel was eagerly searching for opportunities to gain fame and rapid promotion. As it turned out, Kilpatrick almost never got the chance.

![]()

Brigadier General Hugh Judson Kilpatrick

![]()

In the fall of 1862, Kilpatrick was jailed in Washington D.C.’s Old Capitol Prison, charged with conduct unbecoming an officer. Specifically, he was accused of taking bribes, stealing horses and tobacco and selling them, and impropriety in borrowing money. A less resourceful or ambitious man might have been slowed by these circumstances, but not Kilpatrick. In spite of his incarceration, he managed a promotion to colonel of the 2nd New York Cavalry in December 1862. In January 1863, friends in high places and the exigencies of the war prevailed, and Kilpatrick returned to his regiment untainted by the scandal of a courts-martial.5 For most young officers such charges would have been career-ending. Kilpatrick had not only survived unscathed, but emerged from prison a full colonel.

By the spring of 1863 the New Jersey native was in command of a brigade. Major General Alfred Pleasonton, the temporary commander of the Army of the Potomac’s newly-formed Cavalry Corps, arranged for Kilpatrick’s promotion to brigadier general on June 14, 1863. The basis for the recommendation rested upon Kilpatrick’s good performance during the May 1863 Stoneman Raid and the Battle of Brandy Station. On June 28, when Maj. Gen. Julius Stahel was relieved of command and his independent cavalry division was merged into the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps, Kilpatrick took charge of the newly-designated Third Cavalry Division. It was in that capacity that he ordered a foolhardy mounted charge across difficult terrain by Brig. Gen. Elon J. Farnsworth’s cavalry brigade at the Battle of Gettysburg on the afternoon of July 3, 1863, an attack that accomplished nothing but the pointless death of Farnsworth and many of his brave troopers.6

Thanks in large part to the Union victory at Gettysburg, Kilpatrick was not censured for his poor judgment in ordering Farnsworth’s charge. When bloody draft riots broke out in New York City a few days later, Kilpatrick was sent to assist Maj. Gen. John E. Wool and assumed command of the Federal cavalry forces gathered to help quell the disturbances.7 After visiting with his wife and new born son for two weeks, Kilpatrick returned to duty in Virginia.

The Federal and Confederate armies spent a long and bloody fall jockeying for position. Kilpatrick suffered a crushing defeat at the hands of Maj. Gen. James Ewell Brown (Jeb) Stuart’s Confederate cavalry at the Battle of Buckland Mills on October 19, 1863, precipitating a rout known to history as “the Buckland Races.”

When the fall campaign season ended with the armies stalemated along the Rappahannock River, Kilpatrick developed a bold scheme to liberate Union prisoners of war from Libby Prison and Belle Isle in Richmond. If he succeeded, great glory awaited him. Colonel Ulric Dahlgren, a flamboyant 22-year-old one-legged cavalry officer commanded one column of the raid, while Kilpatrick commanded the other. Over Alfred Pleasonton’s vigorous objections, the raid was approved.8

Faced with unexpected Confederate resistance, Kilpatrick was repulsed in front of Richmond and struck hard by Wade Hampton’s rebel troopers at Atlee’s Station later that night. Dahlgren was thrown back at the southwestern defenses of Richmond and killed in an ambush near Stevensburg in King & Queen County, almost forty miles from the Southern capital. Incriminating documents found on Dahlgren’s body suggested that the purpose of the raid was not only the liberation of prisoners of war, but the burning of Richmond and the murder of President Davis and his cabinet. A firestorm of controversy erupted, and Kilpatrick was blamed for the embarrassing debacle. A scathing Detroit newspaper editorial observed that Kilpatrick “cares nothing about the lives of men, sacrificing them with cool indifference, his only object being his own promotion and keeping his name before the public.”9 By this time he had acquired the unflattering nickname of “Kill-Cavalry” because he had repeatedly used up both men and horses in his ongoing pursuit of personal glory. On April 15, 1864, Kilpatrick was removed from command of the Third Cavalry Division.

Meanwhile, General Sherman’s western army (he actually led three armies together in one large group on his drive into Georgia) needed a new cavalry commander. The Western Federal cavalry had fared poorly during the first three years of the war, and Sherman had been looking for someone to bring toughness and aggressiveness to his mounted arm. He had several cavalry commanders to choose from, including George Stoneman, Kilpatrick, and Maj. Gen. James H. Wilson, the overall commander of the cavalry assigned to Sherman’s theater of operations. Wilson had succeeded Kilpatrick in command of the Third Division of the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps. Even though Wilson was younger than Kilpatrick, he was a full major general of volunteers while Kilpatrick was only a brevet brigadier general. Not surprisingly, there was no love lost between the two officers. Sherman resolved this potential conflict by placing Kilpatrick directly under his own command, thereby removing him from Wilson’s authority.

Not long after joining Sherman, Kilpatrick was badly wounded at Resaca during the opening days of the Atlanta Campaign that May. He did not return to duty until late July 1864. By this time Stoneman was in a Confederate prison, leaving Kilpatrick as the commander of Sherman’s cavalry by default—even though Wilson outranked him. Kilpatrick capably led a division of cavalry during Sherman’s March to the Sea and in his subsequent advance through South Carolina and into North Carolina during the winter of 1864.10

For his part, Wilson remained at cavalry headquarters in Alabama developing a new plan. He put together a 16,000-man mounted army and led it on an extended raid into the heartland of the South, eviscerating what remained of the that portion of the Confederacy. Wilson’s army defeated Lt. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest’s cavalry at Selma, Alabama, on April 2, 1865.

Judson Kilpatrick cut an odd figure. He stood only five feet, three inches tall and weighed about 130 pounds. Despite his diminutive size, he was nevertheless a memorable character in a war filled with unforgettable ...