- 388 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

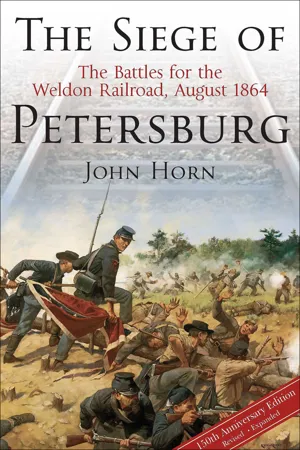

About this book

A revised and expanded tactical study General Grant's Fourth Offensive during the American Civil War.

The nine-month siege of Petersburg was the longest continuous operation of the American Civil War. A series of large-scale Union "offensives," grand maneuvers that triggered some of the fiercest battles of the war, broke the monotony of static trench warfare. Grant's Fourth Offensive, August 14–25, the longest and bloodiest operation of the campaign, is the subject of John Horn's revised and updated Sesquicentennial edition of The Siege of Petersburg: The Battles for the Weldon Railroad, August 1864.

Frustrated by his inability to break through the Southern front, General Grant devised a two-punch combination strategy to sever the crucial Weldon Railroad and stretch General Lee's lines. The plan called for Winfield Hancock's II Corps (with X Corps) to move against Deep Bottom north of the James River to occupy Confederate attention while Warren's V Corps, supported by elements of IX Corps, marched south and west below Petersburg toward Globe Tavern on the Weldon Railroad. The move triggered the battles of Second Deep Bottom, Globe Tavern, and Second Reams Station, bitter fighting that witnessed fierce Confederate counterattacks and additional Union operations against the railroad before Grant's troops dug in and secured their hold on Globe Tavern. The result was nearly 15,000 killed, wounded, and missing, the severing of the railroad, and the jump-off point for what would be Grant's Fifth Offensive in late September.

Revised and updated for this special edition, Horn's outstanding tactical battle study emphasizes the context and consequences of every action and is supported by numerous maps and grounded in hundreds of primary sources. Unlike many battle accounts, Horn puts Grant's Fourth Offensive into its proper perspective not only in the context of the Petersburg Campaign and the war, but in the context of the history of warfare.

"A superior piece of Civil War scholarship." —Edwin C. Bearss, former Chief Historian of the National Park Service and award-winning author of The Petersburg Campaign: Volume 1, The Eastern Front Battles and Volume 2, The Western Front Battles

"It's great to have John Horn's fine study of August 1864 combat actions (Richmond-Petersburg style) back in print; covering actions on both sides of the James River, with sections on Deep Bottom, Globe Tavern, and Reams Station. Utilizing manuscript and published sources, Horn untangles a complicated tale of plans gone awry and soldiers unexpectedly thrust into harm's way. This new edition upgrades the maps and adds some fresh material. Good battle detail, solid analysis, and strong characterizations make this a welcome addition to the Petersburg bookshelf." —Noah Andre Trudeau, author of The Last Citadel: Petersburg, June 1864–April 1865

The nine-month siege of Petersburg was the longest continuous operation of the American Civil War. A series of large-scale Union "offensives," grand maneuvers that triggered some of the fiercest battles of the war, broke the monotony of static trench warfare. Grant's Fourth Offensive, August 14–25, the longest and bloodiest operation of the campaign, is the subject of John Horn's revised and updated Sesquicentennial edition of The Siege of Petersburg: The Battles for the Weldon Railroad, August 1864.

Frustrated by his inability to break through the Southern front, General Grant devised a two-punch combination strategy to sever the crucial Weldon Railroad and stretch General Lee's lines. The plan called for Winfield Hancock's II Corps (with X Corps) to move against Deep Bottom north of the James River to occupy Confederate attention while Warren's V Corps, supported by elements of IX Corps, marched south and west below Petersburg toward Globe Tavern on the Weldon Railroad. The move triggered the battles of Second Deep Bottom, Globe Tavern, and Second Reams Station, bitter fighting that witnessed fierce Confederate counterattacks and additional Union operations against the railroad before Grant's troops dug in and secured their hold on Globe Tavern. The result was nearly 15,000 killed, wounded, and missing, the severing of the railroad, and the jump-off point for what would be Grant's Fifth Offensive in late September.

Revised and updated for this special edition, Horn's outstanding tactical battle study emphasizes the context and consequences of every action and is supported by numerous maps and grounded in hundreds of primary sources. Unlike many battle accounts, Horn puts Grant's Fourth Offensive into its proper perspective not only in the context of the Petersburg Campaign and the war, but in the context of the history of warfare.

"A superior piece of Civil War scholarship." —Edwin C. Bearss, former Chief Historian of the National Park Service and award-winning author of The Petersburg Campaign: Volume 1, The Eastern Front Battles and Volume 2, The Western Front Battles

"It's great to have John Horn's fine study of August 1864 combat actions (Richmond-Petersburg style) back in print; covering actions on both sides of the James River, with sections on Deep Bottom, Globe Tavern, and Reams Station. Utilizing manuscript and published sources, Horn untangles a complicated tale of plans gone awry and soldiers unexpectedly thrust into harm's way. This new edition upgrades the maps and adds some fresh material. Good battle detail, solid analysis, and strong characterizations make this a welcome addition to the Petersburg bookshelf." —Noah Andre Trudeau, author of The Last Citadel: Petersburg, June 1864–April 1865

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Siege of Petersburg by John Horn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The War at its Crisis

At the beginning of August 1864, the fortunes of the United States stood near their low water mark. Those fortunes manifested themselves in the price of gold on the New York Stock Exchange. Traditionally, the price of gold has furnished a pitiless, impartial, inverse index of faith in the established order—the higher the price of gold, the less the faith. On July 11, 1864, as Lt. Gen. Jubal A. Early led a Rebel infantry corps into the suburbs of the Northern capital at Washington, D.C., the price of gold reached its wartime high and the price of a dollar in United States currency reached its wartime low.

The Confederacy had withstood the onslaughts of the two major Union army commands, one launched at the Southern capital in Richmond, Virginia, and the other at the important rail and commercial center in Atlanta, Georgia. The appalling casualties suffered by Federal troops from the beginning of May until the end of July, more than 84,000 in Lt. Gen. Ulysses Simpson Grant’s army group alone, seemed in vain.

Grant, general-in-chief of Northern forces, had failed to take Richmond. Gloom and disgust prevailed among his officers and men in the aftermath of the fiasco at the battle of the Crater at Petersburg, Virginia, on July 30.1

Major General William Tecumseh Sherman had failed to capture Atlanta. In a series of battles, skirmishes and raids lasting from July 20 until August 6, Southerners under Gen. John Bell Hood had halted Sherman’s infantry and decimated his cavalry in their efforts to cut the last railroads into Atlanta.

Rear Admiral David G. Farragut’s victory in the battle of Mobile Bay on August 5 started the price of gold on a decline it would continue until the end of the month. Though reassuring to the financial community, success at Mobile Bay provided little consolation to the Union electorate for the failures at Richmond and Atlanta.

Public sentiment against the war increased in the North. President of the United States Abraham Lincoln encountered threats of forcible resistance when, on July 18, he called for a draft of 500,000 more men. At the request of Congress, he declared August 4 a day of national fasting, humiliation and prayer.

The Secessionists had not merely frustrated the Federals. The Rebels had taken the offensive. General Robert Edward Lee had detached Early’s Corps from the Army of Northern Virginia in early June to march down the Shenandoah Valley and threaten Washington. The move had struck the Northerners a substantial blow. Much as Maj. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson had done in 1862, Early cleared the Shenandoah of Federal troops, diverted reinforcements from the Unionist command threatening Richmond, and shook the United States War Department’s confidence in its general-in-chief’s strategy.

Lee wanted more than this. He wanted to raise the siege of Petersburg and drive the Northerners from Richmond’s doorstep. The war’s heretofore master psychologist pinned his hopes on the effect that Early’s threat to the Union capital would have on the command beleaguering Petersburg. Half the railroads supplying Richmond—the Weldon Railroad and the Southside Railroad—had terminals in the Cockade City, a name Petersburg had acquired because an infantry company raised there had worn rosettes, or cockades, in their hats during the War of 1812. The loss of the Cockade City would put the Federals in excellent position to cut Richmond’s remaining supply lines and isolate the Confederate capital. As Grant believed in overwhelming numbers, Lee reasoned to his staff, detachment of sufficient force to protect Washington from Early would so reduce Grant’s strength that he would withdraw from Petersburg altogether.

Lee’s indirect strategy seemed on the verge of even greater success than it had produced in 1862, when it had merely denied reinforcements to the Unionists in front of Richmond. On the night of July 30, after receiving news that Early had crossed the Potomac into Union territory again, Grant sent the following telegram to Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade, the commander of the Army of the Potomac: “Get all the heavy artillery in the lines about Petersburg moved back to City Point as early as possible.” Then the general-in-chief added ominously: “It is by no means improbable the necessity will arise for sending two more corps there.”2 This message indicates exactly how close to success Lee’s strategy came. Many on both sides, including knowledgeable observers in high places, expected that Lee would soon march his entire army into Union territory as he had in 1862 and 1863.

Panicky Republican politicians clamored for a new convention and for President Lincoln to step aside for a candidate who could win in the November election. More level-headed Republicans pressured Lincoln to abandon abolition as a stated condition of peace and to insist upon the Union alone as peace’s condition. As staunchly Republican a newspaper as the New York Times criticized Lincoln for not negotiating with the commissioners whom President of the Confederate States Jefferson Davis had sent to Niagara Falls to take advantage of Northern war weariness by proposing a peace conference. Threatening to split the Republican vote, Maj. Gen. John Charles Fremont, famous as “The Pathfinder” for his western explorations, entered the presidential race as a radical Republican candidate. The Democrats indulged themselves in optimism.

Just as in 1862, Federal Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton and chief of staff Maj. Gen. Henry W. “Old Brains” Halleck cracked under the strain. In their obsession with Washington’s vulnerability, they ordered Maj. Gen. David Hunter, the Union commander in the Shenandoah Valley, back and forth so many times that he soon lost contact with the enemy. The back-biting Halleck criticized Grant for moving south of James River and not keeping his army group interposed between Richmond and Washington. Halleck also urged Grant to withdraw troops from his front and send them north to enforce the draft against expected resistance, concluding: “Are not the appearances such that we ought to take in sail and prepare the ship for a storm?”3

Lincoln and Grant kept their heads. Their resolve accounted for the difference between 1862, when Lee had driven Union forces from the gates of Richmond and carried the war into the North, and 1864, when Lee remained pinned down in defense of his capital. Both the president and his general-in-chief realized the extremity of the South and that the Confederacy’s only hope lay in a change of Federal administrations.

As general-in-chief, Grant had the virtue of never losing sight of the overall view. He considered the Northern armies a team, and he wanted them to apply continuous pressure on their respective fronts to prevent the enemy from concentrating against any particular Unionist army. The general-in-chief believed that a withdrawal from James River would insure Sherman’s defeat by allowing the Secessionists to shift forces from Virginia to Georgia for a repetition of Chickamauga.

President Lincoln, who had more nerve than any of his advisors, played his part by sustaining Grant against them. The bond between these two men withstood even the tension created by those who thought Grant a stronger presidential candidate than Lincoln and wanted the president to step aside in favor of the general-in-chief.

Before Early’s cavalry had burned Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, on July 30, Grant had resisted Lincoln’s request to come north in person and rectify the situation in the Shenandoah. The general-in-chief thought that his departure from the Petersburg trenches would signify a loss of faith in the strategy that had taken him south of the James. Early’s second incursion into Northern territory created such serious repercussions that during the first week of August Grant finally yielded to the president.

At a conference with Lincoln at Fortress Monroe on July 31, the general-in-chief and the president decided to deal with this crisis—perhaps the crisis of the war—not by abandoning the Siege of Petersburg, but by putting under a single commander the field forces of all four of the Shenandoah’s military departments. On August 2, Grant sent to the Shenandoah Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan to take command of all the troops in the field there. Grant directed Sheridan to pursue the enemy to the death.

Halleck’s quibbling over this order exhausted Lincoln’s patience. The president insisted upon Grant’s personal presence in the vicinity of Washington not so much to protect the capital as to get the Federal forces in the Shenandoah moving aggressively after Early. Lincoln wanted a general in charge, not a bureaucrat.

Hastening by boat and train to Monocacy Station, Maryland, northwest of Washington, Grant laid the foundation for September’s Union victories in the Shenandoah by removing Hunter and placing Sheridan in departmental as well as field command, then reinforcing Sheridan with another cavalry division from the Union army group threatening Richmond, and finally putting Sheridan in charge of a new military division consolidating his own department with three others. For the moment, Sheridan remained untested as an independent commander and uncharacteristically hesitant in the face of exaggerated reports of Early’s strength.

Lee quickly perceived that Grant had sent reinforcements to the Shenandoah. The Virginian persisted in his strategy of threatening the Federal capital. To protect Early, Lee on August 6 dispatched to Culpeper Court House Kershaw’s division of Anderson’s Corps and Fitzhugh Lee’s division of cavalry, both under Lt. Gen. Richard H. “Fighting Dick” Anderson, a West Pointer and Mexican War Veteran who had moved up to corps command after a Confederate bullet put out of action the previous corps commander, Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, at the battle of the Wilderness on May 6. Lee ordered Anderson to thwart any enemy move across the Blue Ridge into the Shenandoah by menacing Washington.4

Federal Pontoon Bridge at Deep Bottom Library of Congress

The Southerners also went on the offensive on the Petersburg front. They took steps to eliminate the Federal bridgehead at Deep Bottom. On August 7, Lt. Col. John Clifford Pemberton prepared to implement a plan that he and President Davis had formulated to drive the Unionists from the Deep Bottom bridgehead. Deep Bottom lay where Four Mile Creek emptied into the end of a wide meander of James River, about twelve miles southeast of Richmond as the crow flies. Brig. Gen. Robert Sanford Foster’s brigade of the Army of the James had held the bridgehead since June 20. A bluff around forty feet high where mulberries and cherries abounded, Deep Bottom afforded Grant access to the north side of the James from Bermuda Hundred. Whenever he wanted, he could mount a threat to Richmond by reinforcing the bridgehead. Elimination of the Deep Bottom bridgehead would require the Federals to cross James River much farther downstream, significantly reducing the danger to the Confederate capital.

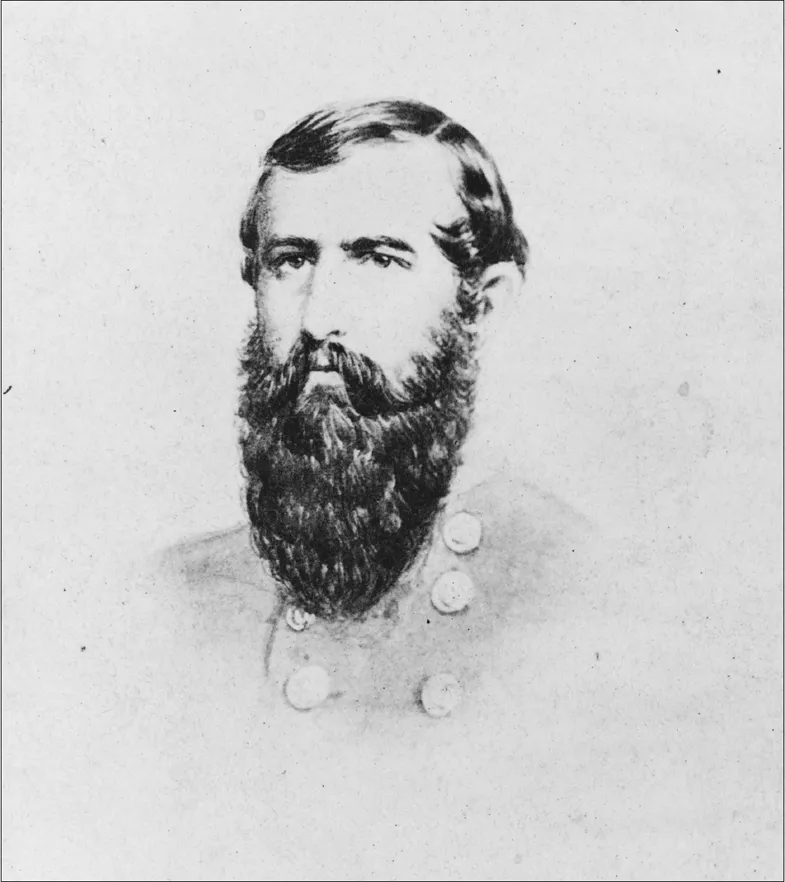

Vanquished by Grant at Vicksburg the previous summer, Pemberton served as a lieutenant colonel of artillery in the Department of Richmond because no Confederate unit warranting a higher-ranking commander would serve under the northern-born former lieutenant general. He planned to bring the pontoon bridges linking Deep Bottom with Bermuda Hundred under the fire of enough artillery to force the abandonment of the bridgehead. Heavy artillery at the foot of New Market Heights would enfilade the bridgehead from the north while rifled fieldpieces at Tilghman’s Gate created a crossfire.

Despite the importance of opening fire as soon as possible, shortages delayed implementation of Pemberton’s plan. They illustrated the immense difference between Northern and Southern industrial capacities. A scarcity of mortars forced Pemberton to supplement the two 10-inch mortars available with four 8-inch howitzers placed with their trails sunk to give the necessary elevation. Positioning the relatively short-ranged howitzers close enough to the pontoon bridges to render the guns effective left them outside the Confederate fortifications at New Market Heights and vulnerable to capture by a sortie from Deep Bottom. A shortage of transportation hampered moving the mortars. Lee’s artillerists at Petersburg had a prior claim on the use of the sole serviceable mortar sling cart in the department. Time ticked away on an opportunity for the Secessionists to deny Grant access to the strategy he had employed the previous month and that he would employ in August and September as well—a right cross thrown at Richmond from the bridgehead at Deep Bottom, followed by a left hook delivered on the Petersburg front.

While Pemberton struggled, Grant faced his own challenges. Returning to City Point on August 9, the general-in-chief narrowly escaped death. That morning Brig. Gen. George H. Sharpe, the assistant provost-marshal-general, informed the general-in-chief that spies had infiltrated the Federal supply base at City Point. Grant’s army group drew virtually all its sustenance from City Point, a port which had grown into a small city with hundreds of buildings and a wealth of supplies beyond Rebel imagination. Fleets of steamboats, sailing vessels, and barges unloaded at its wharves.

Sharpe, a New York lawyer educated at Yale, proposed a plan to detect and capture the spies. Staff officers present at this meeting included Lt. Col. Horace Porter, Grant’s aide-de-camp, the son of a governor of Pennsylvania, and a graduate of Harvard and West Point. Sharpe had just left Grant when, at 11:40 a.m., Porter remembered, “a terrific explosion shook the earth, accompanied by a sound which vividly recalled the Petersburg mine, still fresh in the memory of everyone present.”5 Shells, shot, bullets, timber fragments, body parts and even saddles rained down on the general-in-chief’s headquarters in Appomattox Manor. A bullet wounded the hand of Col. Orville E. Babcock, another aide-de-camp and West Point graduate, but the general-in-chief escaped unscathed. A boat loaded with ordnance stores had exploded, destroying the boat and the wharf at which it lay and killing all the laborers aboard as well as men and horses near the landing. The blast slew 43 and wounded 126.6 By all accounts, Grant himself behaved in exemplary fashion.7

Lt. Col. John C. Pemberton, C.S.A. Library of Congress

John Maxwell, a Confederate spy, had built what he called a “horological torpedo”—a time bomb which contained twelve pounds of powder.8 He and another spy, R. K. Dillard, had entered Federal lines dressed as laborers and headed for the supply base at City Point. Mingling with the worke...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Table of Contents

- Preface to the First Edition

- Chapter 1: The War at its Crisis

- Chapter 2: The Second Battle of Deep Bottom, August 14, 1864

- Chapter 3: The Second Battle of Deep Bottom, August 15, 1864

- Chapter 4: The Second Battle of Deep Bottom, August 16, 1864

- Chapter 5: The Second Battle of Deep Bottom, August 17-21, 1864

- Chapter 6: The Battle of Globe Tavern, August 18, 1864

- Chapter 7: The Battle of Globe Tavern, August 19, 1864

- Chapter 8: The Battle of Globe Tavern, August 20, 1864

- Chapter 9: The Battle of Globe Tavern, August 21, 1864

- Chapter 10: Wrecking the Weldon Railroad, August 21-24, 1864

- Chapter 11: The Second Battle of Reams Station, August 25, 1864

- Chapter 12: The Second Battle of Reams Station, August 25, 1864: The Second Confederate Assault

- Chapter 13: Had Not Success Come Elsewhere

- Table 1: Federal Strength, July 31, 1864

- Table 2: Confederate Strength, July-August, 1864

- Table 3: Casualties

- Table 4: Combat Efficiency

- Appendix A: Orders of Battle, Second Deep Bottom

- Appendix B: Orders of Battle, Globe Tavern

- Appendix C: Orders of Battle, Second Reams Station

- Bibliography