- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

War Surgery 1914–18

About this book

"A most interesting book, both from a World War I historical perspective and from the major changes in medicine that are so well outlined." —

British Journal of Surgery

The First World War resulted in appalling wounds that quickly became grossly infected. The medical profession had to rapidly modify its clinical practice to deal with the major problems presented by overwhelming sepsis. Besides risk of infection, there were many other issues to be addressed including casualty evacuation, anesthesia, the use of X-rays, and how to deal with disfiguring wounds—plastic surgery in its infancy. This book focuses closely on the human aspects of the surgery of warfare, and how developments in the understanding of combat injuries occurred.

Ten essays covering a wide variety of topics, including the evacuation of casualties; anesthesia, shock, and resuscitation; pathology; X-rays; orthopedic wounds; abdominal wounds; chest wounds; wounds of the skull and brain; and the development of plastic surgery. All material is supported by an extensive number of figures, tables, and images.

Those with a passion for the history of this period, even if they have no medical training, will find fascinating information about those surgeons who worked in Casualty Clearing Stations between 1914 and 1918—and laid the foundations for modern war surgery as practiced today.

The First World War resulted in appalling wounds that quickly became grossly infected. The medical profession had to rapidly modify its clinical practice to deal with the major problems presented by overwhelming sepsis. Besides risk of infection, there were many other issues to be addressed including casualty evacuation, anesthesia, the use of X-rays, and how to deal with disfiguring wounds—plastic surgery in its infancy. This book focuses closely on the human aspects of the surgery of warfare, and how developments in the understanding of combat injuries occurred.

Ten essays covering a wide variety of topics, including the evacuation of casualties; anesthesia, shock, and resuscitation; pathology; X-rays; orthopedic wounds; abdominal wounds; chest wounds; wounds of the skull and brain; and the development of plastic surgery. All material is supported by an extensive number of figures, tables, and images.

Those with a passion for the history of this period, even if they have no medical training, will find fascinating information about those surgeons who worked in Casualty Clearing Stations between 1914 and 1918—and laid the foundations for modern war surgery as practiced today.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Setting the scene

Thomas R Scotland and Steven D Heys

On 29 October, 1914, tired remnants of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) were on the Menin Road, some five miles to the south-east of the Belgian city of Ypres. They were at a little village called Gheluvelt, defending the slopes of the Gheluvelt Ridge against the might of two German armies, the 4th to the north of the road, and the 6th to the south. Reinforcing these two armies was a special force called Army Group Fabeck, created for the specific purpose of forcing a way through the British defenders to the summit of the Ridge, and the city of Ypres beyond. The British would then have to retreat to the channel ports, and be knocked out of the war. By most peoples’ standards the Gheluvelt Ridge is a gentle slope, and barely worthy of comment, but in the flat countryside of Flanders it represents a significant topographical feature.

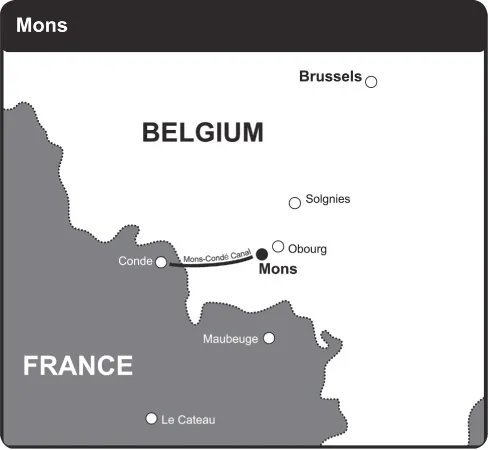

The British were exhausted. A lot had happened since the two army infantry corps and one cavalry division making up the small Expeditionary Force had embarked for France from the south of England under cover of darkness on the nights of 12 and 13 August 1914. They had been fighting and marching almost continuously since Sunday 23 August. On that day, on the left flank of the French 5th Army, they had briefly fought the Germans at Mons and along the Mons-Condé Canal, in Belgium, before making a fighting withdrawal to the South on that Sunday evening. On 26 August at Le Cateau, General Smith-Dorrien’s II Corps had turned round to deliver a stinging blow to von Kluck’s German 1st Army, in a manoeuvre designed to slow down the Germans who were hard on the heels of the British forces, and not giving them a moment’s respite.

Figure 1.1 The Menin Road, looking up towards the summit of the Gheluvelt Ridge from the village of Gheluvelt. (Authors’ photograph)

Figure 1.2 Mons and Mons-Condé Canal, with Le Cateau to the south. (Department of Medical Illustration, University of Aberdeen)

The French 5th Army successfully performed a similar manoeuvre against von Bulow’s German 2nd Army at Guise on 29 August, permitting the tired British to have a rest day, and tend to their blistered feet, which ached after constant marching over cobbled streets of northern France in the baking heat of late summer. Then, with their French allies on their right flank, the British pulled back to the River Marne, less than 30 miles due east of Paris. From there, General Joffre, Commander in Chief of the French forces, launched a major counter-offensive against the Germans between 6 and 9 September 1914, in what became known as the Battle of The Marne. He did so with the addition of a new French 6th Army and with the help of the British forces. It was a decisive action, and brought the German war machine to a shuddering standstill, pushing it into reverse. Now it was the Germans’ turn to withdraw, with the French and British in pursuit.

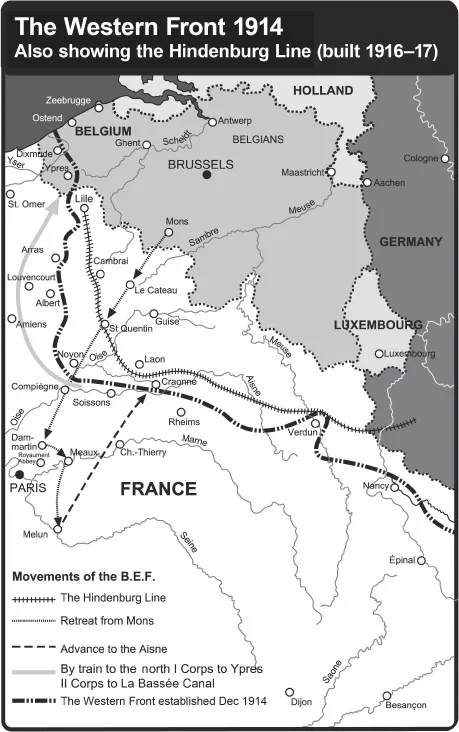

Figure 1.3 The Western Front 1914, also showing the Hindenburg Line (built 1916–17) (Department of Medical Illustration, University of Aberdeen)

The British had marched for more than one hundred and fifty miles since the Battle of Mons, under constant severe pressure, and now at last they had an opportunity to attack. Re-invigorated by the prospect, they and their allies pursued the enemy as they crossed the River Aisne. They had anticipated continuing the pursuit after the crossing, but instead the Germans dug in on the north bank and retreated no further. Another fierce engagement, which would become known as the Battle of the Aisne was fought between 12 and 15 September 1914 and many casualties were sustained. Each side then tried to outflank the other, in a series of moves which became known as the “race to the sea”. Each tried to gain an advantage by getting in behind the enemy forces, and then “rolling up their line”. These outflanking attempts were only brought to a standstill when the opposing armies reached the sandy beaches of the Belgian coast. Soon there were two lines of soldiers facing each other from the Swiss border to the Channel coast, and the Western Front came into being. A war of great movement was about to be replaced by static trench warfare, which would come to characterise the Great War. The advance to the Aisne would be the last piece of open warfare until the spring of 1918.

When troop started to move north in the “race to the sea”, the BEF was transported by train in the general direction of its supply lines to play its part in the unfolding conflict. The original BEF which had fought at Mons on 23 August had two infantry corps in the field, I Corps and II Corps, each with approximately 30,000 men and a cavalry division with approximately 10,000 men. II Corps went north to fight around La Bassée, while I Corps went further north and arrived at the Belgian town of Ypres by mid-October 1914. Reinforcements to meet ever-increasing demands and growing numbers of casualties were arriving as quickly as possible. British III Corps arrived in time for the Battle of The Aisne, and IV Corps in time for the fighting around Ypres in October and November of 1914.

And so it came to be that many British troops found themselves on the Menin Road near Ypres on 29 October. Here the character of the fighting changed dramatically. The Belgian army to the north blocked access to the coastal plain in what became known as the Battle of The (River) Yser, an engagement they only won by opening the dyke sluices and flooding the flat coastal plain from the coast to Dixmuide, thus securing the northern flank of the Allied line for the duration of the war. Here, around Ypres, was the Germans’ last opportunity for a breakthrough, to bring an end to fighting in the West, inflict a defeat on their hated enemy the French and knock the “contemptible” little British Army out of the war. This was to be no outflanking manoeuvre. This was to be a hammer blow of the greatest severity, to punch a hole through the heart of the British defences on the Menin Road. Only then, after first defeating the British, and then the French, would they be able to turn their full attention to deal with the Russian Armies on their Eastern Front.

It was allegedly Kaiser Wilhelm who referred to the British Expeditionary Force as a “contemptible little army”. He probably had meant that it was contemptibly small, which indeed it was, rather than inferring that the soldiers themselves were contemptible. They were in fact a highly trained and hardened professional force, able to fire fifteen aimed rounds a minute using bolt-action Short Magazine Lee-Enfield Rifles. They perhaps performed best in the role of stubborn defence against overwhelming odds, as they were about to prove. There was something symbolically appropriate about the name “Old Contemptible” which the survivors of that small Professional British Army proudly called themselves as 1914 drew to a close.

The British had to call on all their experience to prevent a catastrophic breach of their lines by the Germans. By 31 October, they had been forced to withdraw to the Western, downward slope of the Gheluvelt Ridge, with the city of Ypres to their rear. There they stopped, and there they remained. The Germans never did get into Ypres just two or three miles down the road, and it would be almost four years before the British would re-occupy Gheluvelt.

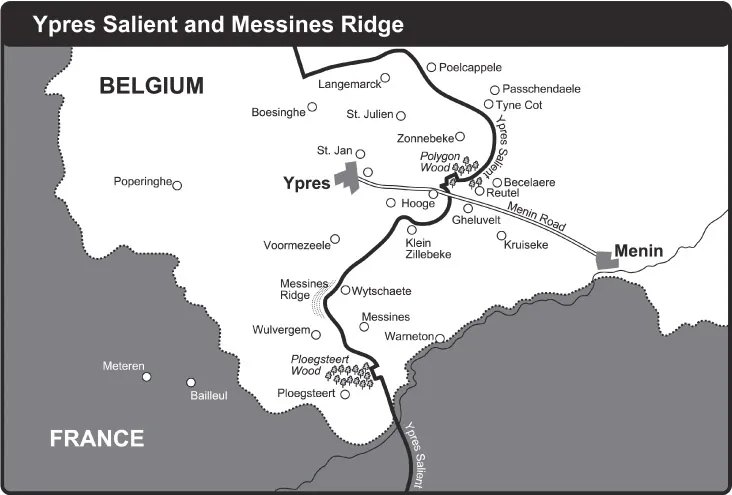

As a result of this action (which became known as the Battle of Gheluvelt), and other engagements by the British, French and Belgian forces, the Allies came to hold a roughly semi-circular area of ground, bulging out against the German positions with the city of Ypres as a centre point, and with a radius of approximately 4 miles. Thus was born the infamous Ypres Salient. The Germans held the higher ground, on the ridge, and they looked down on the lower and more disadvantageous positions held by the Allies.

A salient is simply a line which protrudes outwards against the enemy position. Fighting in a salient meant that enemy artillery could be sited all round the perimeter, and defenders could be fired at from the front, from the sides, and even from the rear. There were many examples of salients throughout the length of the Western Front, but when men talked about “The Salient”, they invariably referred to the killing zone around Ypres.

Opposing forces spent four years killing and maiming each other in the confined area of The Salient. There were three major engagements around Ypres, which subsequently became classified as battles, although there was fighting here every day for the duration of the war. Even when “nothing of importance” happened, men were killed or wounded in the Salient. The heavy fighting around Ypres in the closing weeks of 1914 became known as the 1st Battle of Ypres and resulted in the formation of the Ypres Salient. British casualties amounted to 58,155 killed, wounded or missing.1 Adding casualties from prior engagements at Mons, Le Cateau, the Marne and the Aisne, it is estimated that by the end of 1914 only 1 officer and 30 other ranks remained of each battalion of 1,000 strong which had gone to France in August 1914.2 The loss of these men was a severe blow, because they were a highly trained force of hardened professionals of great experience. In that sense they were irreplaceable, and it would be a long time before their successors acquired a matching level of ability.

Figure 1.4 Western slope of the Gheluvelt Ridge looking down towards the city of Ypres. (Authors’ photograph)

Figure 1.5 Ypres Salient and Messines Ridge (Department of Medical Illustration, University of Aberdeen)

Figure 1.6 An “Old Contemptible” – he had fought at Mons, Le Cateau, the Marne and 1st Ypres. He died on a day when “nothing of importance” happened on the Western Front. (Authors’ photograph)

There were two other major battles around Ypres. On 22 April 1915, the 2nd Battle of Ypres began when the Germans used poison gas for the first time on the Western Front. Chlorine was discharged from gas cylinders late in the afternoon of the 22nd, between the villages of Poelcapelle and Langemarck, a few miles from Ypres. This resulted in a complete collapse of the northern segment of The Salient, which became saturated by chlorine gas. French colonial troops occupying the trenches here fled, leaving a huge gap. Fortunately, the Germans had made no preparation to fully exploit the advantage gained, and so things were not as bad as they might have been, thanks to the men of the Canadian 1st Division, who had recently arrived on The Salient, and whose quick thinking and rapid deployment saved the day. While this was a crisis for the Allies, they retrieved the situation and The Salient contracted down to a tight defensive position round Ypres, making it easier to defend. The 2nd Battle of Ypres lasted approximately a month and British losses amounted to 59, 275 killed, wounded and missing. This figure includes losses sustained by the Canadian 1st Division and the Indian Corps.3

The 3rd Battle of Ypres began on 31st July 1917. The British strategic aim was to break out from The Salient and capture the Belgian ports of Ostend and Zeebrugge. This would deny their use to the Germans as U-boat bases. This was wishful thinking, and the offensive became completely bogged down in the mud at the village of Passchendaele in November 1917, where men fought and died in the most appalling conditions. This battle involved Australian, New Zealand and Canadian Divisions as well as British and South African troops. Total losses were 244,897 killed, wounded and missing, according to Neillands.4 According to Prior and Wilson the losses were 275,000, with 70,000 killed.5 The reality is that no one knows precisely how many died and sank forever into the mud.

As will be seen in Chapter 2, figures exist for numbers of casualties admitted to, and treated by, the various casualty clearing stations during the 3rd Battle of Ypres. The numbers of wounded are staggering, and one may wonder how on earth the medical services coped with so much work. If a surgical team working in a modern fully equipped hospital of today had more than twenty patients admitted during a 24 hour period, it would consider itself busy. Casualty clearing stations during 3rd Ypres were regularly dealing with 200 to 300 admissions a day, before passing the “on call” on to an adjacent clearing station while working through the caseload of admissions.

More than a quarter of a million British and Commonwealth soldiers died in the confined area of the Salient during four years of the Great War. There are approximately 150 British Military cemeteries within a five-mile radius of the city of Ypres. Some are small and secluded, with only a few dozen burials, while others are huge with several thousand graves. After the war, many tiny cemeteries and isolated graves were relocated to designated “concentration” cemeteries, to allow reclamation of the land. There were dead buried almost everywhere on The Salient, and squads of men searched the battlefield methodically, digging up the scattered dead, and taking them to be reburied in a chosen concentration cemetery. The biggest British military cemetery in the world, and an example of a concentration cemetery, is located near the village of Passchendaele at Tyne Cot, where there are 11,908 graves.

Because of the ravages of time, and the destructive nature of shellfire, 8,366, or 70% of the soldiers ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- List of Contributors

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Setting the scene

- 2 Evacuation pathway for the wounded

- 3 Anaesthesia, Shock and Resuscitation

- 4 Pathology during the Great War

- 5 X-Rays during the Great War

- 6 Developments in orthopaedic surgery

- 7 Abdominal wounds: Evolution of management and establishment of surgical treatments

- 8 Penetrating chest wounds and their management

- 9 Wounds of the Skull and Brain

- 10 Development of Plastic Surgery

- Helion Books

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access War Surgery 1914–18 by Thomas Scotland, Steven Heys, Thomas Scotland,Steven Heys in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & World War I. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.