![]()

Part One

1975

During this first year under study – and the seventh of the Troubles – some 44 soldiers or former soldiers would die in or as a direct consequence of the Troubles. The figures showed a reduction from the previous year, but it still meant that, on their own doorstep, and in the thirtieth anniversary year of the ending of the Second World War and at a time of supposed peace, the British Army was losing almost a soldier a week.

![]()

1

January

The Provisional IRA had declared their ‘festive’ ceasefire a few days prior to the start of the New Year and this was, as usual, treated with contempt by the Loyalists, and suspicion and caution by the Army. However, on the second day of the year, an IRA press conference announced that the current ceasefire would be extended, not indefinitely as observers had hoped, but until 17 January. It was, however, a longer extension than had been expected and talks between the Northern Ireland Office (NIO) and the Republicans continued in secret.

In the new-found spirit of talks, representatives of some of the leading Ulster Unionist parties met to discuss matters with Merlyn Rees, Labour’s Northern Ireland Secretary. They were deeply suspicious of the IRA’s motives and mistrustful of any contact between their enemies and the Security Forces. An allegation at the time that there had been clandestine contact between the British Government and Republicans was later confirmed and the Loyalists’ paranoia of a British pull-out were greatly heightened during this period of regular contact.

CEASEFIRE SURREALISM

Major Andrew MacDonald, King’s Own Border (now the Duke of Lancaster’s Regiment)

My third tour of NI took place over the years 1974/5 as a platoon commander in the Lower Falls (if I recall correctly from November to February). We were stationed in Mulhouse Mill with other company bases in the inner West Belfast area including the Shankill. One of the abiding memories of that tour is the Christmas ‘ceasefire.’ My use of inverted commas is done advisedly because it created a somewhat surreal atmosphere whereby we had to patrol with rifles slung and operate in a ‘non-confrontational’ manner. We had to be careful to avoid activity which might attract displeasure and so be reported to the various ‘Incident Centres,’ one of which one was at the top end of our patch on the Falls Road/Dunville Park corner; more of that later.

[The IRA ceasefire began in late 1974 and lasted until the following January. This was also a period in which leading IRA members under their guise of Sinn Fein politicians were allowed to legally carry weapons for personal protection. This greatly angered their sectarian rivals in the UVF and UFF who were not allowed the same privileges. Suffice to say, they also possessed large armouries but to their chagrin, theirs were not ‘legal.’]

Quite what our top level people were thinking this would achieve, by this measure is hard to fathom out, because to us at street level, it was clear that the so called ceasefire was just an excuse to allow both PIRA and OIRA (as well as INLA and other mad dog dangerous groups on both sides of the sectarian divide) to regroup, and to get on with the inter-factional scrapping. To be fair to the policy and decision-makers, this conflict was all still very new to the British Army. Our last pieces of action were both tactically and politically far removed from our previous experiences, and we were only four years into a totally different type of campaign. Little did we know that Op Banner would last for nearly three decades.

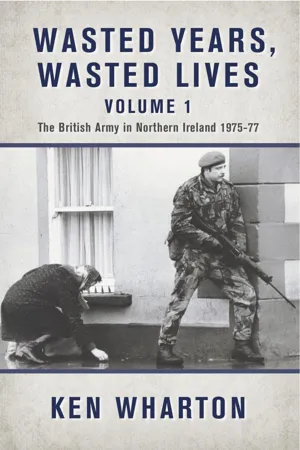

Early days of the Troubles; welcome to the Falls Road. (Mark ‘C’)

An incident of note is recalled in the author’s first book (A Long Long War; Voices From The British Army in Northern Ireland, 1969-88, pp.201-202) where we mounted a long term OP in a roof opposite the one of these ‘Incident Centres’ on the Falls Road. What the intelligence services gleaned from our relatively unsophisticated operation was of enormous value, in piecing together who the players were and what they were getting up to under this cloak of political expediency.

All in all, the tour in our patch was quiet in terms of bullets, bombs and military casualties though it’s worth remembering that this was the time of the Birmingham bombs, a huge Belfast City Centre bombing campaign and the introduction of the Prevention of Terrorism Act. Looking back with a wider perspective is more interesting than the pure military street level activity. There was so much else going on: the area was being extensively redeveloped so that the mill-dominated street layout with its rabbit warrens of back alleys was to be replaced by smart new, low rise housing meaning that many of the areas were partially or fully derelict; the power struggle was nearly over between the Officials and Provisionals (the latter group won out); the political movements were starting to shape up; and the Westminster Government was showing (perhaps understandable?) timidity none of which was helped, it is interesting to note, by some of our cousins in the USA who took a couple of decades to wise up to who they were raising money for. Despite all the low key military activity there was a continuous undercurrent of threat running along in the background and we knew that the ceasefire was only going to continue as long as they wanted it to.

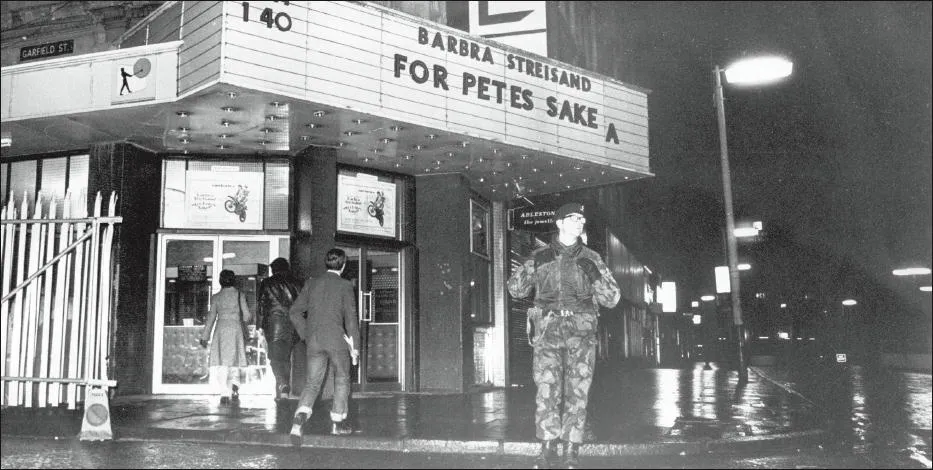

Life goes on for these Belfast residents as even the sight of an armed soldier can’t stop a night out. (Belfast Telegraph)

Many of us can look back at our tours in the early 70s and reflect on how much more sophisticated it got in the next two decades: from improvements to our kit and operational procedures, to developments in the enemy’s tactics; from the importance of the intelligence war to the political manoeuvrings in front of and behind the scenes. But the bit that didn’t change was the performance and resilience of our soldiers; consistently professional, cheerful and flexible. The author’s books bring this out better than any I have read and looking at the stories that came out of Iraq, many other conflicts and now Afghanistan, we should be proud to have had the privilege of serving in such an organisation that continues to deliver the highest of standards in the face of adversity.

On Wednesday, 1 January 1975, Harold Wilson, then British Prime Minister, met with leaders of the main Churches in Northern Ireland, at a secret location. As a consequence of this meeting and further contacts with the IRA’s Army Council, an announcement was made the following day by the Republicans. The IRA announced an extension of its ceasefire and this stage of the ceasefire was to last until the 17 January. Further secret talks were held between officials at the Northern Ireland Office (NIO) and representatives of the IRA to discuss the continuation of the increasingly fragile truce. A consequence of which was witnessed the following day, when a meeting between representatives of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) with Merlyn Rees, then Secretary of State for Northern Ireland broke up over arguments about the contacts between government officials and the IRA.

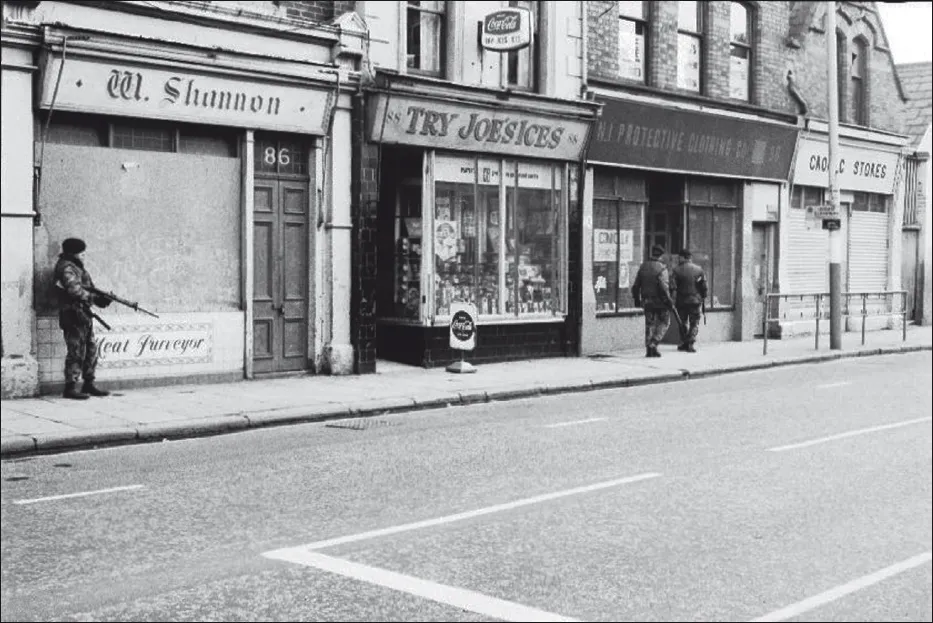

Just window shopping; troops on patrol in Falls Road area. (Mark ‘C’)

Finally, on Thursday 16 January 1975 at midnight, having previously announced that it would call off its ceasefire, the IRA truce came to an end. Merlyn Rees announced that he would not be influenced by arguments supported by the bomb and the bullet.

As previously mentioned, on the morning of Thursday 16 January, the IRA announced that the ‘war’ would resume at midnight that same day, but grieving had already started in Northern Ireland and soon that would be extended to other parts of the United Kingdom. On the 10th, John Green (27) a known IRA member who had recently escaped from the Long Kesh internment camp was found dead at a house near Castleblaney, Co Monaghan in the Irish Republic. Green from Lurgan in Co Armagh was named in the Republican ‘roll of honour’ as a Captain. He had been staying in a safe house where he was cornered by a Loyalist death squad which included at least one of the UVF men responsible for the Miami Showband massacre, of which we shall read more later.

There were of course the usual accusations from Provisional Sinn Fein and other IRA apologists, of collusion between the Army and Loyalists and of course the plausible but unlikely theory that an SAS team had penetrated the border and carried out the killing. When Merlyn Rees, the Northern Ireland Secretary of State, was pressed for his reactions to the announcement that the ceasefire was over, he merely pointed out that he was not prepared to continue discussions with men who believed in political change through the bomb and the bullet. Danny Morrison’s future mantra of the ‘Armalite and the ballot box’ strategy was still some time in the future. Meanwhile across the Irish Sea on the British mainland, the IRA’s England team (sometimes known as the ‘England department’) watched and waited, eager to find more targets. They had the atrocities of Birmingham, M62, Woolwich and Guildford behind them and they were clearly prepared to carry out with alacrity, the IRA Army Council’s bidding. Like all terrorist cells, they could be patient and were aware that others had taken the fall for at least one of their atrocities – the M62 Coach bomb for example – and confident in the knowledge that there were further ‘fall guys’ who would take the blame for at least two others.

That time was not long in coming and on the first Sunday – the 19th – after the ending of the ceasefire, the England team struck twice in London within a three-hour period. A gun team opened fire at the entrance to the Portman Hotel in London’s West End at 08:00, approaching in a car and then driving off at high speed. At least one machine-gun was used and five people were injured in the indiscriminate spraying. At 11:00, the Carlton Tower Hotel in Knightsbridge was attacked in similar fashion and more hotel guests were wounded. The attack, which was thought initially, to have been the responsibility of Arab terrorists, was later attributed to the Provisional IRA.

On that same day, an innocent child became the first IRA victim of the resumption of hostilities in Forkhill, Co Armagh. An IRA unit had abandoned a van packed with explosives outside the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) police station in Forkhill on the morning of the 19th. Army bomb disposal experts had coolly towed the vehicle to a nearby field and then detonated it, harmlessly. However, an unnoticed device had failed to explode and as a couple of young boys from a neighbouring farm drove cattle nearby, it detonated, killing little Patrick Toner (7) instantly. Some 12 months earlier, an IRA rocket had detonated in the bedrooms of the Toner farm but no-one had been hurt; the Angel of Death was patient, however and the young boy became another innocent victim of the men of evil.

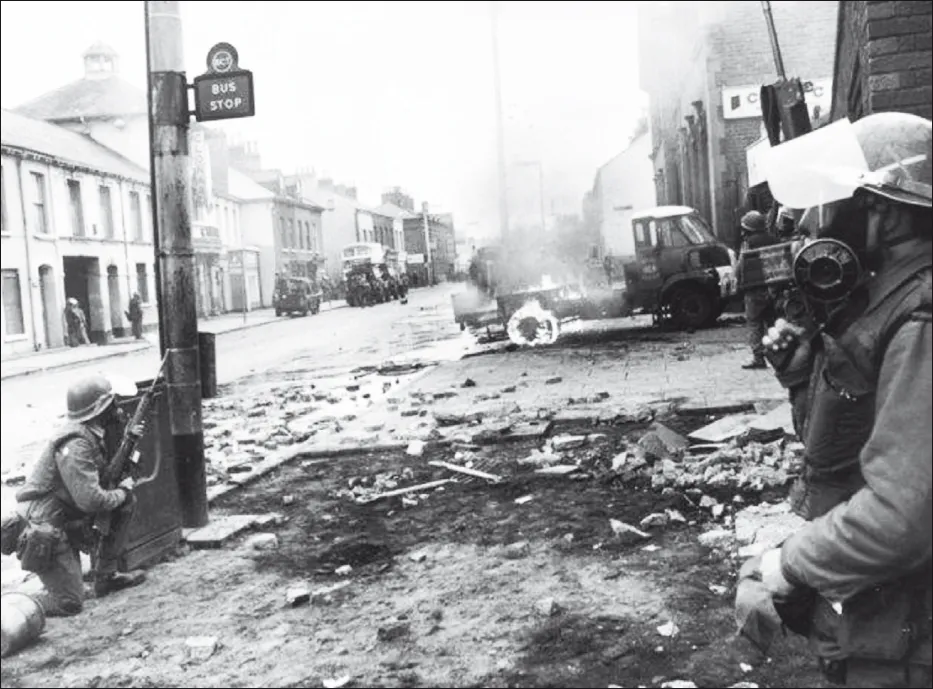

VIOLENCE ON THE STREETS

Lieutenant Colonel (Retired) R M McGhie, OBE

During our tour we deployed the entire company to Unity corner in Belfast virtually every other Saturday with another company in reserve in the side streets. This was a well-known flashpoint where the Shankill marchers, often the masked ranks of the paramilitary Ulster Defence Association (UDA) marched past the nationalist community living in the flats who were themselves reinforced by the hard-line nationalists from the nearby Ardoyne and New Lodge areas. We deployed behind barbed wire to separate the factions and our arrest squads, snatch squads we called them, were ready to spring forward to seize identified rioters preferably before the stoning became too heavy and the petrol bombs began their flaming trajectory towards us. All the side streets had been blocked off with physical barriers to stop us being outflanked and to contain the violence where we were in the best position to control it. The pattern was the same; shouting, spittle, stones, petrol bombs and then the sniper, sometimes all five activities at once. Often riots had a lull at 6 o’clock when the protagonists wanted to go home and see their efforts on the television news. Some riots lasted well into the night until the rioters wanted to go home to bed. We had no choice but to stay there until it was over.

Riots were never a pleasant experience for soldiers but good leadership and discipline, excellent training and good protective equipment gave them confidence as well as protection from the worst effects of the violence. Petrol bombs always looked highly dangerous on the 6 o’clock news but a few simple training drills such as stepping back and keeping riot shields flush to the ground reduced their real effect except in some tragic cases where security force personnel were injured.

Bessbrook Mill base. (Mark ‘C’)

SOUTH ARMAGH: INTRODUCTION

Corporal Martin Wells, 1st Bn, Royal Green Jackets

1RGJ were to deploy to South Armagh and as part of that deployment, the Reconnaissance Platoon were to depart two weeks early in order to liaise with the outgoing unit, The Duke of Edinburgh’s Regiment, (DERR) and familiarise themselves with the Battalion area. We duly left our barracks in Dover, Kent, having spent the previous two months training in our main role of Close Observation. After arriving at Bessbrook Mill, just outside of Newry, we split into various groups and departed to the different Company locations, scattered around South Armagh. I was assigned to go down to Crossmaglen, but before that, I spent several days in Bessbrook as part of the Recce Platoon Commanders group, along with L/Cpl Dave Brown, who was his Radio Operator.

During those few days at Bessbrook we got to know the various agencies who were attached to the Bessbrook battalion and, where possible, tried to get out on the ground, on any current operations that the DERRs might be conducting. Given why we had arrived early, this last might seem all too obvious. But in practice, it was quite difficult. Units hosting advance parties of other units sometimes seem unable to help with their requirement for a whole variety of reasons. In South Armagh for instance, the availability of helicopters, or even seats on helicopters, was crucial when planning operations. Everybody and everything moved by helicopter. Having even four or five unscheduled passengers turn up, who were not vital to an operation, could cause a major headache in the overall planning of helicopter movements. As luck would have it, two or three days after our arrival, Captain ‘J’ was allocated three places at very short notice, on a resupply helicopter going out to an ongoing operation. Him, Dave Brown and I, grabbed our kit and weapons, and rushed down to the LZ within about ten minutes.

As we climbed into the helicopter, I was unsure exactly where we were going, but we ended up at a small, square complex of unoccupied farm buildings, next to a small lane that ran across the Border into Republic of Ireland. This crossing point was known as Hotel 22. The farm buildings and the small orchard attached to them, were secured by a platoon of the DERR, and were about to be searched by members of 9 Independent Para Squadron of the Royal Engineers.

Several days earlier, a patrol from the DERRs had visited the buildings as part of a routine patrol and discovered a large tanker trailer full of diesel fuel parked in the courtyard. Given the amount of fuel, and the fact that diesel is one of the main components used in the manufacture of homemade bombs, it was thought to be suspicious enough to monitor, and the decision was made to insert a covert patrol in the buildings. Two nights later, a car arrived at the farm buildings from the direction of Republic of Ireland, with two occupants. The car parked just a few yards into the South, and while one man remained in the vehicle, a second got out, walked a few yards over the border, entered into the courtyard and began checking the diesel tanker. The DERR’s patrol broke cover and captured this man, but not before he alerted his companion, who escaped in the car. An operation was then mounted to properly secure the buildings and search them more thoroughly in the daylight.

It was around 11am, that myself, Captain ‘J’ and Dave Brown, arrived on the resupply helicopter. Our arrival seemed to be unannounced, and I got the impression, a little unwanted. There were already in t...