eBook - ePub

The Chickamauga Campaign: A Mad Irregular Battle

From the Crossing of Tennessee River Through the Second Day, August 22–September 19, 1863

- 672 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Chickamauga Campaign: A Mad Irregular Battle

From the Crossing of Tennessee River Through the Second Day, August 22–September 19, 1863

About this book

"Far surpasses anything anyone else has ever done about this pivotal engagement." —

The Journal of America's Military Past

Chickamauga, according to soldier rumor, is a Cherokee word meaning "River of Death." It certainly lived up to that grim sobriquet in September 1863 when the Union Army of the Cumberland and Confederate Army of Tennessee waged bloody combat along the banks of West Chickamauga Creek. Here, award-winning author David Powell embraces a fresh approach that explores Chickamauga as a three-day battle, rather than the two-day affair it has long been considered, with September 18 being key to understanding how the fighting developed the next morning. The second largest battle of the Civil War produced 35,000 casualties and one of the last clear-cut Confederate tactical victories—a triumph that for a short time reversed a series of Rebel defeats and reinvigorated the hope for Southern independence. At issue was Chattanooga, the important "gateway to the South" and logistical springboard into Georgia.

Despite its size, importance, and fascinating cast of characters, this epic Western Theater battle has received but scant attention. Powell masterfully rectifies this oversight with the first of three installments spanning the entire campaign. This volume includes the Tullahoma Campaign in June, which set the stage for Chickamauga, and continues through the second day of fighting on September 19.

Powell's magnificent study fully explores the battle from all perspectives and is based upon fifteen years of intensive research that has uncovered nearly 2,000 primary sources from generals to privates, all stitched together to relate the remarkable story that was Chickamauga.

Includes illustrations

Chickamauga, according to soldier rumor, is a Cherokee word meaning "River of Death." It certainly lived up to that grim sobriquet in September 1863 when the Union Army of the Cumberland and Confederate Army of Tennessee waged bloody combat along the banks of West Chickamauga Creek. Here, award-winning author David Powell embraces a fresh approach that explores Chickamauga as a three-day battle, rather than the two-day affair it has long been considered, with September 18 being key to understanding how the fighting developed the next morning. The second largest battle of the Civil War produced 35,000 casualties and one of the last clear-cut Confederate tactical victories—a triumph that for a short time reversed a series of Rebel defeats and reinvigorated the hope for Southern independence. At issue was Chattanooga, the important "gateway to the South" and logistical springboard into Georgia.

Despite its size, importance, and fascinating cast of characters, this epic Western Theater battle has received but scant attention. Powell masterfully rectifies this oversight with the first of three installments spanning the entire campaign. This volume includes the Tullahoma Campaign in June, which set the stage for Chickamauga, and continues through the second day of fighting on September 19.

Powell's magnificent study fully explores the battle from all perspectives and is based upon fifteen years of intensive research that has uncovered nearly 2,000 primary sources from generals to privates, all stitched together to relate the remarkable story that was Chickamauga.

Includes illustrations

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Chickamauga Campaign: A Mad Irregular Battle by David A. Powell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Molding an Army:

Summer 1863

Major General William Starke Rosecrans was a frustrated man in the late summer of 1863. Other Union commanders had won great victories or fought tremendous battles that summer. Grant had taken Vicksburg. Meade defeated Lee in Pennsylvania. From Washington President Abraham Lincoln, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, and Maj. Gen. Henry Wager Halleck all prodded Rosecrans to end his inaction and accomplish something of like stature in Middle Tennessee. Rosecrans, a perfectionist, refused to move before he was ready. “General Halleck is very urgent,” he complained to his chief of staff, Brig. Gen. James A. Garfield on June 12, “and thinks that I am the obstinate one in this matter.” At the end of that month Rosecrans answered his critics with what he regarded as a campaign of brilliant maneuver by marching his Army of the Cumberland across a broad front on several axes. The operation outflanked and outfoxed Confederate Gen. Braxton Bragg’s outnumbered Army of Tennessee from its stronghold at Tullahoma. Outgeneraled, Bragg retreated without a major battle, arriving at Chattanooga in the southeast corner of the state, on July 3.1

Rosecrans’s triumph was overshadowed by the electrifying news of the twin Union victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg during the first week of July. Even though both successes came burdened with heavy casualty lists, they also defeated enemy armies in the field. The Army of the Cumberland’s feat was accomplished with minimal loss, but Bragg’s Confederates escaped largely intact. Rosecrans’s protests fell on deaf ears. Sensing a potential end to the long and bloody rebellion, Washington politicians urged him to press on. The Tullahoma campaign might have been technically brilliant, but Washington also had a point: Bragg’s army had escaped intact and would still have to be defeated, likely several times, before a decision could be reached.

Unlike the Federals in Virginia and Mississippi, whose supply lines were short and waterborne transport rendered them essentially unbreakable, the Army of the Cumberland was forced to depend almost entirely upon long and vulnerable railroads for its lifeline. The point of origin for supplying the army was Louisville, Kentucky. From there, the tracks of the Louisville & Nashville road snaked south through central Kentucky and northern Tennessee to terminate at Nashville. A critical rail bridge at Munfordville, Kentucky and the “Big South” Tunnel at Gallatin, Tennessee, demonstrated the vulnerability of these rail lines. Damage to track could usually be repaired quickly, but bridges and especially tunnels represented critical choke points that could not be replaced or re-bored easily. In August 1862, as the Confederates invaded Kentucky, Confederate raider John Hunt Morgan and his men caved in the tunnel at Gallatin by ramming a burning train into it at full speed. The tunnel was out of service for more than three months, leaving the Army of the Cumberland bereft of much-needed supplies for weeks on end.2

From Nashville, the supply line was taken up by the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad, which curved southeast to Stevenson, Alabama, before crossing the Tennessee River at Bridgeport and entering Chattanooga from the west. The N&C had its share of bridges (notably over the Elk, Duck, and Tennessee rivers), as well as at least two more important tunnels. Bragg destroyed the bridges during his retreat, but he wasn’t as creative as Morgan had been: instead of blasting the tunnels he filled them with debris that left them largely undamaged. Within a couple of weeks, Federal army engineers restored the road to operating condition as far south as Bridgeport.

With the head of his army at Bridgeport, Rosecrans was forced to expend a considerable amount of time and resources to protect nearly 350 miles of vulnerable track and infrastructure. One reason the Yankees could not simply press on after the Tullahoma operation was because the Army of the Cumberland needed to stockpile mountains of supplies at forward bases in order to be prepared for anticipated interruptions of its tenuous logistical lifeline. Those bases, along with the rails themselves, had to be protected with garrisons, blockhouses, and patrols. A huge base was established at Murfreesboro, Tennessee, near the old battlefield of December 1862. “Fortress Rosecrans” was intended to hold a permanent garrison of several thousand men and supplies for 100,000 troops in the field for as long as three months.

Fortunately, the Department of the Cumberland did not have to bear alone the entire responsibility for defending the line. Most of the Louisville & Nashville Railroad fell under the jurisdiction of the Union Department of the Ohio, currently commanded by Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside. Burnside replaced Maj. Gen. Horatio G. Wright, who was transferred to the Army of the Potomac in May 1863. The Department of the Ohio was charged with defending Kentucky and ensuring the security of the L&N, and, after Burnside’s arrival, was given the mission of invading East Tennessee. Lincoln had long cherished the liberation of that region since it was a hotbed of pro-Unionist sentiment deep in Secessia, and those Unionists had suffered at the hands of Rebel authorities intent on cracking down against anti-Confederate resistance. Rosecrans also endorsed the idea, for he thought his own plans would materially benefit from the strategy. Earlier that March he had urged Wright that “the way to stop the raid into Kentucky is to prepare to invade East Tennessee; threaten in several directions and you will scare them.” He was no less enthusiastic about Burnside’s proposed operations.3

Because it wasn’t on the front lines, however, the Department of the Ohio was often called upon to shift troops to other theaters. Many of the forces in Rosecrans’s growing command came from Kentucky. Burnside had no sooner arrived in the department with two divisions of his IX Corps when he was called upon to forward many of these troops to General Grant operating against Vicksburg. As a result, the department’s strength wildly fluctuated. On March 31, 1863, Burnside’s strength amounted to slightly more than 22,000 men present for duty. By April this number had swelled to nearly 33,000, and by May Burnside had 38,000 troops. After reinforcing Grant, the department’s June strength fell to 32,000, and by August 10 peaked at nearly 40,000 troops. From this last total, however, Burnside needed to organize a field force for the move into East Tennessee, which amounted to nearly 28,000 men. Of the remaining 12,000, roughly 7,000 of those were stationed in or still forming in the states of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, and Ohio; leaving only 5,000 Federals to protect the vital rail lines through Kentucky. It was hoped that with Union troops occupying Knoxville and Confederate cavalry raider John Hunt Morgan captured and imprisoned in Ohio, this paltry force would be sufficient to maintain the security of the exposed line.4

During the two months following Tullahoma, Rosecrans carefully assembled the supplies and troops he would need for the next great leap southward. Chattanooga sat across the Tennessee River embedded in the mountain fastness of the southern Appalachians. Wresting it from the Rebels would be no easy task.

Although enthusiasm for Rosecrans was waning among many key Federal politicians, such was not the case within the Army of the Cumberland. Rosecrans assumed command of what was to become one of the three great Federal armies of the war when he replaced Don Buell at the head of the Army of the Ohio on October 27, 1862. Buell had recently fought the battle of Perryville to an unsatisfying result, and when the Rebels escaped Kentucky without further damage, the Lincoln administration decided Buell simply had to go. The job fell to Rosecrans only after Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas turned down the appointment in what Thomas apparently hoped would be a gambit to retain Buell. Instead, the administration moved on to find someone else, and that someone was Rosecrans. The decision angered Thomas, at least initially, but his personal friendship with Rosecrans smoothed over whatever frustration he felt, as did a re-shuffling of dates of rank so that Rosecrans was now the senior officer. The end result was that what could have been a troubling relationship with his senior subordinate became instead a solid working partnership.5

The Union Army of the Ohio grew dramatically during Buell’s tenure. His command, organized into five divisions, was spread across Middle and West Tennessee in the summer of 1862, until the Confederate incursion into Kentucky brought Buell racing north in pursuit. Once at Louisville, Buell incorporated a host of new regiments—some of which had been in uniform only a few days—and reinforcements arrived from other theaters to coalesce into a massive new command of 11 divisions informally divided into three corps-sized “wings.” The necessarily rapid command changes and reassignments did not always work to the benefit of crafting an effective, cohesive organization. In the wake of the disappointing stalemate that was Perryville, the army’s structure stabilized into multi-division commands led by Maj. Gens. George Thomas, Thomas L. Crittenden, and Alexander McDowell McCook. However, when Rosecrans took the reins the entire army was still officially designated as the “XIV Corps,” with each of the aforementioned officers leading only an ad-hoc wing.

Rosecrans set about to immediately reorganize and train his command. Given the recent influx of thousands of new men, he spent a considerable amount of time on drill and discipline. The last two months of 1862 were spent putting the command in fighting trim, but he had little time to accomplish much before pressure from above demanded he take the field against the Confederates gathered around Murfreesboro, Tennessee. Near the end of December Rosecrans felt he was ready to advance. The resultant battle of Stones River (also known as the battle of Murfreesboro) was a hard-fought contest among the cedars and rock outcroppings along the banks of that stream. Both sides planned to attack, but the Rebels struck first. The early morning assault routed Rosecrans’s right wing and nearly collapsed his army on December 31. The Yankees grimly hung on, and eventually the Confederate army and its commander Braxton Bragg fell back, yielding the field and the chance to claim victory to Rosecrans and his men.

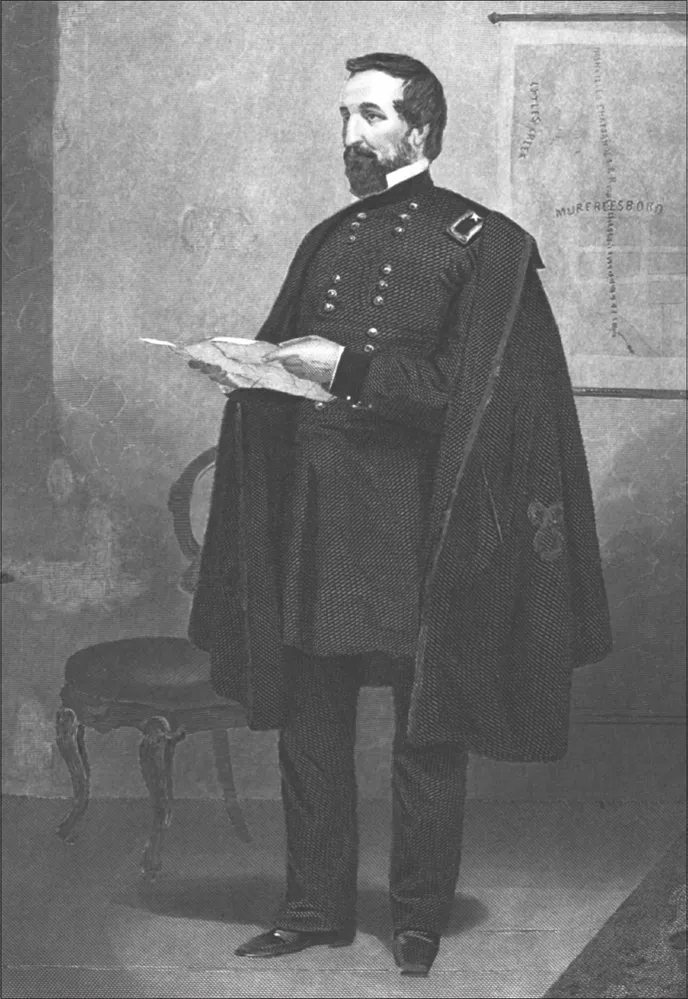

William Starke Rosecrans in the Spring of 1863.

Tennessee State Library and Archives

Tennessee State Library and Archives

The margin of success was a narrow one. Both sides lost about equally in the fight, and though exhausted by the bloody slugfest, neither army was destroyed. Further stalemate was the result. Rosecrans’s first offensive managed to gain only about 30 miles before grinding to a halt as he dug in around Murfreesboro. Bragg fell back to the next defensible terrain, near the towns of Shelbyville and Wartrace. Neither army enjoyed a significant advantage in numbers. As a result, this near-parity produced an inactivity that lingered far longer than either commander intended—much to the dismay of their respective governments in Washington and Richmond.

Rosecrans used this time to plan, re-forge the army into a war-fighting machine of his own creation, and become better acquainted with his commanders. Likewise, the pause also allowed his men to become more comfortable with their new commander.

* * *

The man now steering the helm of the Army of the Cumberland was a member of the West Point class of 1842, which produced 17 Civil War general officers. Though both men were West Pointers and professional soldiers, Rosecrans was Buell’s opposite in many ways: boisterous and outspoken where Buell was “cold and formally polite.” The two men shared at least one characteristic —“unflagging in energy.” Rosecrans lacked prewar combat experience, having missed the Mexican conflict, but had done well so far in this struggle. He had played an instrumental role in early successes in West Virginia, which helped propel George B. McClellan to such heights in Virginia in 1862, and since then led semi-independent commands at Iuka and Corinth. His successful defense of Corinth, coming just a week before his orders to replace Buell, contributed favorably in his getting tasked for the new command.6

William Starke Rosecrans was born on September 6, 1819, in Sunbury, Ohio, just north of the state capital at Columbus. His family was prosperous. His father Crandall Rosecrans was a farmer, a businessman and a pillar of the community. Though many Confederates would later refer to Rosecrans as “Dutch” or “German,” mistaking him for an immigrant soldier like Franz Sigel or Carl Schurz, in fact Rosecrans was a sixth generation American, baptized in the Church of England, of mixed Dutch and English descent. The first ‘Rosenkrantz’ arrived in New Amsterdam in 1651. William’s great-grandfather fought in the Revolution, and his father served on the Canadian frontier in the War of 1812. Soldiering and patriotism were imbued in the new arrival almost from birth.7

Rosecrans’s family couldn’t afford to pay for his education, and so what learning he did acquire was haphazard, and amounted to less than a year’s formal schooling. Instead, Rosecrans read, sought out tutors, and where possible, taught himself. He worked as a clerk in his father’s and others’ business ventures. In 1837 he successfully applied for an appointment to the Military Academy at West Point, entering as a member of the class of 1842. One might expect him to struggle with the rigors of academia, given his lack of classroom experience, but instead William Rosecrans flourished. Always in the top ten percent, he graduated fifth in a class of 51. Fellow classmates included James Longstreet, Alexander Peter Stewart, Earl Van Dorn, and Daniel Harvey Hill. William T. Sherman, George H. Thomas, and Bushrod Rust Johnson were two years ahead of him; Ulysses S. Grant, a year behind. Simon Bolivar Buckner was two years behind, in the class of 1844. The careers of all these men would be intertwined in the years to come.8

While West Point was primarily an engineering school during the nineteenth century, the young Ohioan found time to pursue two outside interests: religion and military history. All cadets were required to attend weekly church services, which at the time were Episcopalian. In his reading, however, Rosecrans developed an interest in Catholicism so intense that he not only converted to the religion of Rome three years after graduation, but he also convinced his younger br...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Prologue: Tullahoma: June 24-July 4, 1863

- Chapter 1: Molding an Army: Summer 1863

- Chapter 2: The Army of Tennessee: Summer 1863

- Chapter 3: A River to Cross: August 16 to September 8, 1863

- Chapter 4: Cat and Mouse in the Mountains: September 8-11, 1863

- Chapter 5: McLemore’s Cove: September 11, 1863

- Chapter 6: A Second Frustration: September 12-15, 1863

- Chapter 7: Bragg Essays a New Plan: September 15-17, 1863

- Chapter 8: Reed’s Bridge: Friday, September 18, 1863

- Chapter 9: Alexander’s Bridge: Friday, September 18, 1863

- Chapter 10: Night Moves: Night of September 18-19, 1863

- Chapter 11: Opening Guns at Jay’s Mill: Saturday, September 19: Dawn to 10:00 a.m.

- Chapter 12: Slugging It Out in Winfrey Field: Saturday, September 19: 9:00 a.m. to 11:00 a.m.

- Chapter 13: Bragg and Rosecrans React: Saturday, September 19: 7:00 a.m. to Noon

- Chapter 14: The Battle for Brock Field: Saturday, September 19: 11:00 a.m. to 1:30 p.m.

- Chapter 15: Governed by Circumstances: Saturday, September 19: 11:00 a.m. to 2:30 p.m.

- Chapter 16: Viniard Field: Davis Opens the Fight: Saturday, September 19: 2:00 p.m. to 3:00 p.m.

- Chapter 17: Viniard Field: Hood Engages: Saturday, September 19: 2:30 p.m. to 4:30 p.m.

- Chapter 18: Viniard Field: Carlin Comes to Grief: Saturday, September 19: 2:30 p.m. to 4:30 p.m.

- Chapter 19: Viniard Field: Benning Attacks: Saturday, September 19: 4:30 p.m. to 5:30 p.m.

- Chapter 20: Johnson Flanks Van Cleve: Saturday, September 19: 3:00 p.m. to 4:00 p.m.

- Chapter 21: Breakthrough in Brotherton Field: Saturday, September 19: 4:00 p.m. to 5:30 p.m.

- Chapter 22: We Bury Our Dead: Saturday, September 19, 4:00 p.m. to 5:30 p.m.

- Chapter 23: Shoring up the Center: Saturday, September 19: 5:30 p.m. to 7:00 p.m.

- Chapter 24: Return to Winfrey Field: Saturday, September 19: 3:30 p.m. to 9:00 p.m.

- Chapter 25: Securing the Flanks: Saturday, September 19: All Day

- Appendix 1: Order of Battle with Strengths and Losses