![]()

Chapter 1

December 1862 - June 1863

“The devil ne’er hated holy water with half the bitterness that these lovely young Winchester girls hated us.”

— James M. Dalzell, 116th Ohio Infantry

The

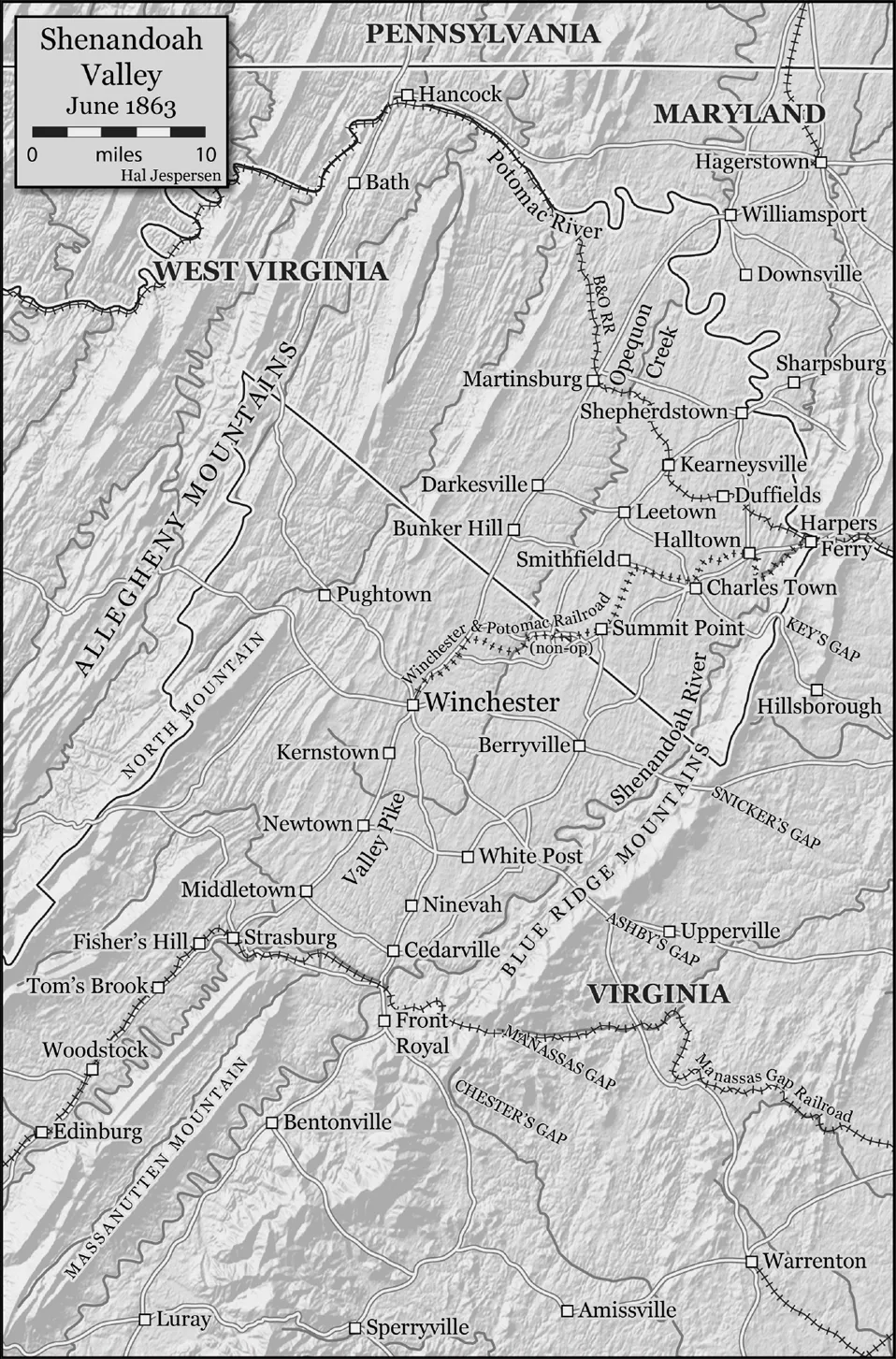

town of Winchester, Virginia, occupied a strategic place in the Lower Shenandoah Valley. The macadamized Valley Pike—a major north-south route of commerce—ran through the historic town north from Staunton down the scenic valley to the Potomac River and beyond into rural Maryland and, eventually, Pennsylvania. The fertile region was once home to many Indian tribes, including the Shawnee nation, and witnessed bloody intertribal wars with the Iroquois, as well as conflicts with the Catawba and others. In the mid-1700s, white settlers, mostly Quakers, Germans, and Scots-Irish from New York and Pennsylvania, supplanted the Indians and spent the next century establishing farms, mills, and light industry. The rich soil enabled farmers to prosper. Orchards produced a wide variety of fruit, most notably apples, and the fields sprouted a host of crops. Therapeutic mineral springs abounded, and several became popular resorts.

1By the middle of the 19th century, Winchester featured gas lights, sidewalks, dozens of tidy brick storefronts, popular hotels and taverns, and a handsome iron-fenced county courthouse built in the Greek Revival style. Stately brick or stone homes lined the main streets, indicative of the town’s prewar wealth. Since the late 1830s, the Winchester & Potomac Railroad had offered a convenient outlet for farmers and merchants to ship their wares north 31.5 miles through Summit Point and Charles Town to Harpers Ferry, where the standard gauge tracks intersected the extensive Baltimore & Ohio system. From there, the goods moved in every direction.2

Panoramic view of downtown Winchester taken in 1894 by an unknown photographer; looking southeast from the Main Fort. Handley Regional Library

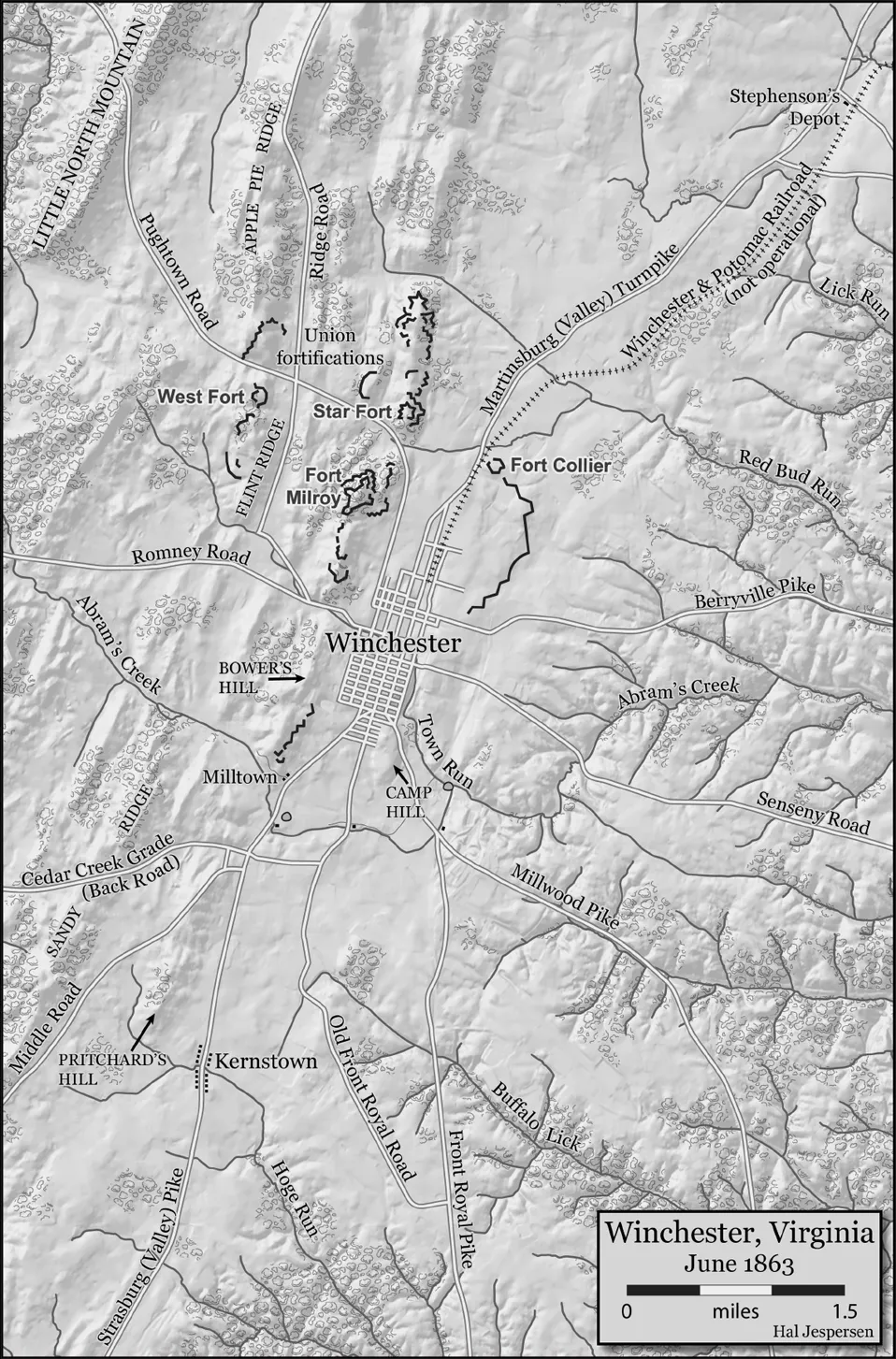

Winchester had developed into an important center of regional commerce and the seat of Frederick County. Good roads radiated out of the town (clockwise) north to Martinsburg, [West] Virginia, Berryville to the east, Millwood to the southeast, Front Royal to the south, Strasburg to the southwest, Romney to the west, and finally, Pughtown to the northwest leading to Berkeley Springs, [West] Virginia, and on to Hancock, Maryland. Several secondary roads also fed Winchester, including the Senseny Road to the east and the old Front Royal Road (also known as Paper Mill Road) to the south. Several meandering watercourses cut across the hilly terrain forming steep ravines and ditches. The most important of these streams included Opequon Creek to the south, and closer to town, Abram’s (also called Abraham’s) Creek, Town Run, and Red Bud Run.3

A series of roughly parallel ridges and low mountains dominated the landscape, the most prominent being pine-covered Little North Mountain west and northwest of Winchester. Northeast of this high ground was the lower Apple Pie Ridge, named for the abundant orchards populating the area. A low extension of Apple Pie Ridge known as Flint Ridge lay between the Pughtown and Romney roads. Closer in toward town on its immediate southwestern side was the broad plateau of Bower’s Hill (sometimes called Potato Hill for its most notable early crop), with the Valley Pike bordering much of its eastern slope. The southern extremity of this ridge was often called Milltown Heights after several nearby woolen, paper, and flour mills. The most notable of these was a three-story, triple-pillared stone mill along Abram’s Creek, near the Valley Pike, which was owned by Issac Hollingsworth. A two-mile wooden mill race provided water power for the old mills, several of which dated from the turn of the century. The creek and race continued eastward across the Valley Pike before winding north past the Front Royal Road, where the race terminated at another of the prolific Hollingsworth family’s string of mills. The stream continued on from there, taking an abrupt easterly turn before emptying into Opequon Creek.4

South of town, at the intersection of the Valley Pike and Millwood Pike, was Camp Hill, so named because of the troops who pitched their tents there during times of war. Near it, Cemetery Hill sported multiple adjacent graveyards—including separate ones for fallen Union and Confederate soldiers—as well as the town’s main civilian cemetery. Well to the southwest toward the village of Kernstown, the terrain was highlighted by the low tree-covered Sandy Ridge and a broad and relatively open hill on the Samuel R. Pritchard farm, crisscrossed by numerous old stone walls. In recalling the March 1862 battle of Kernstown, a soldier wrote, “the country was level and cultivated, with patches of woodland…. In our center and just to the right [west] of the turnpike was a high, conical elevation, called Pritchard’s Hill. This hill was under cultivation. From its slopes and summit there was a fine view of the entire field. It furnished good positions for some of our batteries,” he added, “and an admirable screen for troops and maneuvers.”5

According to the 1860 census, Winchester boasted 4,403 inhabitants, including 655 free blacks and 708 slaves. The early years of the war sparked a mass exodus of young white men into the Confederate army, and more than a few nervous residents fled to escape the conflict. Anyone who could read a map or even a newspaper had fair warning that war would come often to the important Lower Shenandoah Valley community. More than half of the populace had departed by the end of the war’s second year. Control of the Valley, its critical transportation network, and vast food supplies was of great strategic importance to both North and South. As a result, Winchester changed hands more than 70 times during the Civil War, and had thus far witnessed considerable fighting during the 1862 Valley Campaign. The town’s two newspapers, the Republican and the Virginian, ceased operation in early 1862. Soldiers of the occupying 5th Connecticut Infantry used the Virginian’s printing press in March to produce their own paper.6

The hard hand of war first paid Winchester a visit in the spring of 1862, when Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks and 6,500 Union soldiers marched in to occupy the strategic town. Banks was an influential Republican politician from Massachusetts, his high rank more the result of his political clout than his military prowess. On May 25, 1862, Maj. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson and some 17,000 Confederates marched north from Front Royal and attacked Banks on Bower’s Hill in what would eventually come to be known as the First Battle of Winchester. Banks was unable to defend the town and was driven out in a wild rout. Jackson, who had no political clout at all, owed his rank to his experience and military prowess, which he would demonstrate time and again over the coming months. The beaten Unionists retreated nearly 40 miles to the Potomac River and crossed to the far bank at Williamsport, Maryland. Banks suffered more than 2,000 casualties to Jackson’s 400. The Winchester fighting was Stonewall’s first major victory in his Shenandoah Valley Campaign, a success that siphoned away thousands of Union soldiers from Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign opposite Richmond, Virginia, and the defenses of Washington. The Rebels’ subsequent plundering of the massive Union supply depot at Winchester earned for Banks the unflattering sobriquet “Commissary Banks.” Banks’ defeat raised the question of whether a small force of infantry could hold Winchester against a numerically superior enemy force. By the early summer of 1863 the issue was about to be put to the test once more: thousands of Union soldiers were once again garrisoned in and around Winchester.7

After the occupying Confederates departed in late November 1862, Brig. Gen. John Geary marched his Federals into town on December 3, only to march back out soon thereafter when reports of smallpox crossed his desk. Rebel cavalry returned for a short time, only to ride out on the 15th. Meanwhile, Union Brig. Gen. Robert H. Milroy had directed his French-born subordinate, Brig. Gen. Gustave Paul Cluseret, to lead a 3,000-man force of infantry, artillery, and cavalry into the city. Cluseret arrived on Christmas Eve to the consternation of much of the populace. One young lady named Laura Lee bemoaned, “The wretched, horrible Yankees are here again!” Indeed they were, and many more were on the way. On New Year’s Day, 1863, Milroy marched the rest of his division into downtown Winchester.8

Milroy’s command, a division of the Eighth Corps, came under the jurisdiction of the Middle Department, which had been created earlier in the war to oversee and handle troops within the Mid-Atlantic States. Milroy reported to Maj. Gen. Robert C. Schenck, a former Ohio congressman, diplomat, and veteran of the disastrous 1862 Valley Campaign. Badly wounded in the right arm at Second Bull Run in late August, Schenck was now in charge of the Middle Department with his headquarters in Baltimore, Maryland. It was Milroy’s job to protect the Lower Shenandoah Valley from Winchester while Brig. Gen. Benjamin F. Kelley controlled the Union defenses of the upper Potomac River from his headquarters at Harpers Ferry. The composition of Milroy’s force fluctuated throughout his time in Winchester, but it usually consisted of three brigades under General Cluseret (and his eventual successor Brig. Gen. Washington L. Elliott), Col. Andrew T. McReynolds, and Col. William G. Ely.9

Those citizens of Winchester of the Confederate persuasion felt Milroy’s iron fist. Soon after his arrival, his policies prompted the exit of another round of refugees when he strictly enforced the provisions of President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation and establish firm Federal control over what Milroy perceived to be an unruly and rebellious populace. On January 1, 1863, the general assembled his entire command, galloped along the lines of his reunited division brandishing his sword above his head, and cried out, “This is Emancipation Day!” According to a soldier in the 122nd Ohio Infantry, “The whole division responded with resounding cheers. I looked, and the sun was just rising to usher in the first day of real liberty this republic ever saw.” Most of Winchester’s citizens did not share the Buckeye soldier’s enthusiasm for emancipation.10

On January 5, Milroy issued a bold proclamation of his own emblazoned with the provocative headline “Freedom to Slaves!” and announced that he intended to “maintain and enforce” Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. Anyone who resisted its peaceful enforcement would be “regarded as rebels in arms against the lawful authority of the Federal government and dealt with accordingly.” Typical of Milroy’s early targets was Berkeley County plantation owner Philip De Catesby Jones, a member of a prominent long-time Shenandoah Valley family. Union Generals Robert Patterson and Nathaniel Banks had earlier deported several of Jones’ slaves from Virginia. Milroy now finished the task by sending the rest of them under army escort north across the Potomac. In total, the pro-Confederate Jones lost seventeen slaves in this manner.11

Milroy proved to be an equal opportunity squabbler. In addition to the Virginians, he argued with some of his senior officers, including a public spat with General Cluseret that caught the attention of the townspeople. Mary Greenhow Lee reported that Cluseret was upset with Milroy’s emancipation policy and that “he did not come here to fight for negroes, & to arrest women, & that is contrary to the usages of war to refuse to feed prisoners.” The determined Milroy forced Cluseret to relinquish his command and leave Winchester in mid-January, but the distraught Frenchman did not officially resign his commission until March.12

“My will is absolute law,” Milroy bragged to his wife Mary on January 18. “None dare contradict or dispute my slightest word or wish. The secesh here have heard many terrible stories about me before I came and supposed me to be a perfect Nero for cruelty and blood, and many of them both male and female tremble when they come into my presence to ask for small privileges, but the favors I grant them are slight and few for I confess I feel a strong disposition to play the tyrant among these traitors.” He did so uniformly, incurring the hatred of anyone not an ardent Unionist. “Hell is not full enough,” he later scorned. “There must be more of these Secession women of Winchester to fill it up.”13

The saucy tongue of one young secessionist woman became almost mythical. During the winter, Milroy directed his men to seize hay, fodder, corn, and other forage from Confederate sympathizers in the region, and to deny the sale of such items to anyone judged disloyal to the Union. When a party of soldiers visited the farm of a poor man named John Arnold and carried off a small hayrick, the man’s daughter, Laura, went to the general to beg for its return, or for a permit to obtain forage for the family’s cow, whose milk was the chief support for the family. “You shall not have it, unless your father will take the oath,” demanded Milroy. “Are you loyal?” he supposedly asked her. “Yes,” she replied. He began to write the permit before inquiring, “To the United States?” “To the Confederacy, of course,” Laura replied. After conversation concerning how the cow would star...