eBook - ePub

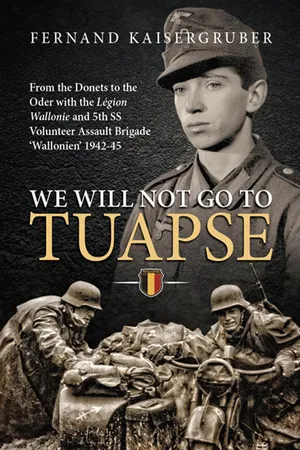

We Will Not Go to Tuapse

From the Donets to the Oder with the Legion Wallonie and 5th SS Volunteer Assault Brigade 'Wallonien' 1942–45

- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

We Will Not Go to Tuapse

From the Donets to the Oder with the Legion Wallonie and 5th SS Volunteer Assault Brigade 'Wallonien' 1942–45

About this book

A soldier with the German Army's Wallonian Legion chronicles his experience as a foreign volunteer for the Nazi war machine during WWII.

A french-speaking Belgian, Fernand Kaisergruber volunteered to fight with the military force that occupied his country. His detailed chronicle of that time reads like a travelogue of the Eastern Front campaign. Until recently, very little was known of the tens of thousands of foreign nationals who fought with the Germans. Kaisergruber's book sheds light on issues of collaboration, the experiences and motives of volunteers, and the reactions they encountered in occupied countries.

Kaisergruber draws upon his wartime diaries, those of his comrades, and his later work with them while secretary of their postwar veteran's league. Although unapologetic for his service, Khemakes no special claims for the German cause. He writes instead from his firsthand experience as a young man entering war for the first time. His narrative is full of observations of fellow soldiers, commanders, Russian civilians, and battlefields.

A french-speaking Belgian, Fernand Kaisergruber volunteered to fight with the military force that occupied his country. His detailed chronicle of that time reads like a travelogue of the Eastern Front campaign. Until recently, very little was known of the tens of thousands of foreign nationals who fought with the Germans. Kaisergruber's book sheds light on issues of collaboration, the experiences and motives of volunteers, and the reactions they encountered in occupied countries.

Kaisergruber draws upon his wartime diaries, those of his comrades, and his later work with them while secretary of their postwar veteran's league. Although unapologetic for his service, Khemakes no special claims for the German cause. He writes instead from his firsthand experience as a young man entering war for the first time. His narrative is full of observations of fellow soldiers, commanders, Russian civilians, and battlefields.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access We Will Not Go to Tuapse by Fernand Kaisergruber in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

From Peace to War

My early childhood and my youth were happy and carefree, even privileged. There was nothing to excite me to go and see something different. I had no extenuating circumstances, as the military interrogators delight to say, nor have I ever claimed such! What I have laid claim to, precisely and jealously, is complete responsibility for my commitment! Even if the environment in which I lived could undoubtedly explain the course of this evolution, I would disavow that, or at least a good part of it, since even though the choices of my older brothers were similar to mine, my parents and my sister did not espouse them at all!

Ever since I was 13 or 14 my friends were mostly older than myself. I hung out with my brothers’ friends and embraced the politics of one of them. I did not miss a political gathering – whether it was at the local REX in the Rue Mercelis, at the “Zonneke”, on the move, in the chaussée de Wavre at Auderghem or at the Sports Palace. I was at Lombeek Ste. – Marie and also at Place Keym – at Watermael – to receive the defrocked Abbé Moreau. The soirées, the “weekends”, were well attended.

My youthful age did not prevent me from recognizing connections between the conduct of certain authorities, notably religious. This developed according to circumstances and, more precisely, regarding the conduct of our parish priest, for whom, despite everything, I had a certain respect, at least until the day when I was able to confirm, with a certain irony, his incoherence; his duplicity.

We lived 200 to 300 meters from a worker’s housing estate, a staunchly Red housing estate, where JGS (Jeunes gardes socialiste) [Socialist young guards] and Faucons Rouges1 [Red Falcon youth movement] were more numerous than the “good parishioners” – that is self-evident – and the Catholic scouts, which I belonged to until the day when, very paradoxically, they decided that I had ideas that were, on the whole, not at all orthodox!

Due to proximity and the force of circumstances, I also had friends among the “Reds”. How could it have been otherwise? The more so since I did not have the same prejudices as certain priests and other “adults”. I did indeed say “certain”, but, in all truth, a large number – and, among these “Reds”, there were certainly men of good faith (honest men, as one puts it) – very good fellows. But our parish priest had an entirely different opinion. He believed that there were respectable people and that there were others who were not at all so – thus, one good day he went to find my father to tell him that “one” had seen me talking or playing with those people. No less than that!

My father, who was, nevertheless, very close to the parish priest when he was a member and even president of different congregations and other parish associations, replied very politely and also diplomatically that I was, doubtless, in the process of developing my judgment and also my perspective. When the parish priest, with such good intentions, then departed, my father nevertheless advised me to keep an eye on my relationships and to sort them out, if necessary.

When, a little later, the 1937 elections began – where Léon Degrelle was face to face with Van Zeeland and the right-thinking people were, little by little, separated from me – I asked myself under what influences, for I could not imagine that it was due to the advice of our parish priest. I asked myself if I had not dreamed all this, for from the first collections of election posters that I saw, and all the world could see them, this Catholic, right-thinking youth was now united as a good family ought to be with all those that I had been exhorted to shun, denying me even the right to talk to them. [Tr. Note: Liberals, Socialists and Catholics united for Van Zeeland as a coalition candidate against Degrelle.] Together they put up posters vaunting the merits and fundamental honesty of Van Zeeland. They drank the glass of friendship in the local bistros and quickly united to beat us in an apparently pre-ecumenical spirit, against which we had not the slightest ally!

If I had been as naive as our parish priest thought, I would have been quite astonished, but I was not so at all, alas. On the contrary, it caused me to reflect on the constancy and inconstancy of the … “Moral Authorities”!

During the Van Zeeland2 scandal I remember approaching Van Zeeland along with some of my comrades as he was leaving the church in the quarter and shouting, “We want REX, the Van Zeeland scandal!” while thrusting the newspaper at him.

I also remember a long wait at the top of a tall telephone pylon of the sort that existed at that time. It was on the boulevard du Souverain, at the foot of l’avenue Chaudron, at the moment of the elections. We had stretched a big white sheet with one or another electoral slogan on it around the crown of the pylon. When we were going to descend, two policemen – holding their bicycles with their hands – passed and stopped at the foot of our high perch. We thought that they had seen us and were waiting for us. In actual fact, it was not that at all, but pure chance. They chatted away for nearly an hour. All the same, we remained stuck up there, exposed to the four winds, waiting until they left!

The soirées at the local Rex meeting room on the rue des Charteux did not lack for animation or, at times, anxious waiting when we hoped for the miracle to finance the publication of the next day’s paper. The euphoria of the elections of 1936, the consternation after those of 1937, but never discouragement! I don’t believe that I have ever seen such political fervor, met such fervid devotion, later, in any other party.

It was often very late when we returned in the evening, after the meetings or after we had put up the election posters, and it was rare that we returned alone. We then made chips or crêpes and ate in gay company until late in the night, while my parents slept upstairs, or, at least, gave the impression of so doing. The crazy ambiance of these meetings thus continued in a small group of friends. It is necessary to have known this fervent and dynamic atmosphere to better understand the later repercussions.

There was the war in Spain and the prayers for Franco. There was the campaign in Abyssinia. I felt more sympathy for the “Duce” than for the “Caudillo”. Thus we passed through all these political developments to arrive at the international Munich accords, the German-Soviet Pact, the Anschluss and the “phony war” to the actual war! My brothers were mobilized, one stationed at the Albert Canal, the other in the Hautes – Fagnes.

On the evening of 9 May, 1940, I go to bed as usual, without any apprehension other than the latent anxiety of my circle of acquaintances since the declaration of war by the “Allies” on 3 September, 1939. When I open my eyes the next day, waking from sleep, I rapidly have a feeling of something strange. It is a feeling that something unusual has awakened me. I hear what sounds like fireworks exploding, and it is broad daylight. The sun shines on the drapes, a few rays penetrate into the room and cut through the shadow. Intrigued, I spring to my feet and tear open the drapes. The sun immediately floods my room. Little white clouds suddenly appear here and there in the sky, followed immediately by the sound of explosions. I think of anti-aircraft practice firing at aircraft, but do not see any [planes] at first. It is only a little later that I see first one, then another, then – shortly thereafter – a third, flying off, barely clearing the hedges.

The sky is marvelously blue and clear, without the least clouds other than the few little puffs from the anti-aircraft fire. I am now certain that it really is anti-aircraft fire. The temperature is exceptionally mild, despite the hour of the morning, for I feel that it is still very early. A glance at my watch tells me that it is barely six o’clock.

I am puzzled for a moment, not knowing what to think. But soon the thought of the war occurs, which, at first, I reject, but which returns and will not let go of me. It is almost a certainty! It is all taking place over the Etterbeek barracks and the parade ground. Other than that, everything is strangely calm. There is no traffic yet. It is still too early, it is true. The household now begins to stir. Certainly my father and my sister are also waking up. A moment later they are in my room and talking with me about the spectacle taking place before us. We then go downstairs and turn on the radio. The radio confirms that it is, indeed, the war! Communiquées alternate with a message from the king, then military march music.

Washing up is quickly taken care of. All this time the anti-aircraft fire continues and other sounds of aircraft mix in the din. Whistling and sharp cracks, much closer, shake the air and one’s nerves. We go down to the cellar, dragging along the mattresses of the vacant bedrooms. We place them in front of the windows of the food cellar and the laundry, which is only half underground.

The noise becomes a bit more distant; we go into the street to see what is happening. The neighbors also come out and engage in conversation. Thick clouds of smoke immediately appear a hundred meters from here in the avenue des Princes, and we head that way. When we get there we find that it is the house of a certain V.T. – an insurance agent, I believe – that is burning, or the one beside it. I do not know exactly which of the two he lives in. The roof is on fire. An incendiary bomb has pierced it. Another bomb is sitting on the tracks of the streetcar line, just in the groove of a rail. It seems to me that it is a hexagonal cylinder, six or seven centimeters diameter, 35 to 40 centimeters long. It is made of two parts and has a sort of little nipple on one of the faces. One of the parts seems to me to be aluminum, the other of a different metal.

Here I meet a friend, Freddy A., the son of a neighbor. On the fringe of the group of adults, we talk about what is going on, in our fashion, and our thoughts crystallize into certainty: we will not go to school today, nor, doubtless, in ensuing days. The war is really on. Other preoccupations quickly vanish, to put it frankly, before this agreeable perspective.

While the adults worry most particularly about the incendiary as they wait for the firemen, and while some attempt to extinguish it, Freddy and I are more interested in the incendiary bomb that is on the rail, and we approach it. We conclude that if it has not caught fire, it is because it has not been armed, and we pick it up, holding it in our hands, passing it back and forth, to examine it. Curious! The little nipple moves and goes down into the body of the cylinder when it is pressed! Now that it has been pressed, I do not dare to let go of it after Freddy remarks that he thinks that the bomb will be triggered when I release it. A bit worried, I do not dare release my pressure.

Now the adults notice what we are doing and pull back, saying that we are crazy. All of a sudden our confidence returns. I ask Freddy to bring me bit of wood, which he pulls off a lilac bush in a little garden. We place it on the nipple and I tie the whole thing up tightly with a handkerchief. People call us all sorts of names and want us to put the thing back where we found it. Someone brings over a stepladder and places it on the tracks near the little bomb. Another person puts some red cloth on top of [the stepladder] to attract attention so that, he says, a streetcar will not run over it without noticing it. That makes us think of a bullfight, but already Freddy and I are looking for other games, thinking of other projects and going elsewhere. The fire is already extinguished. Only the attic is burned.

The days that follow are not lacking in excitement. I see at least two priests arrested, flanked by civilians. Already the civilians are substituting for the judicial authorities. It is decidedly a Belgian mania. It is a hint of what is to come in 1944 and 1945! The adults affirm in all seriousness that there are a number of parachutists among us! It also seems that the enameled metal signs vaunting the virtues of a chicory “qui a bu boira” have messages on their back directed to the fifth column! So, in derision, we follow the example of the adults, tearing down certain signs, assured that no one will dare say anything to us! And if someone were to tell us that we were rascals, we are only following the example of the adults!

Many people are running around with their noses in the air, hoping to discover a paratrooper coming down on them from the sky, preferably unarmed, no doubt! A unit of the Belgian Army arrives, I believe on 11 May, and takes position on the level ground above the quarry 200 meters from our house, rising to the street. Lieutenant Yvon M., the officer of this unit, stays at our house. The next morning English soldiers arrive, equipped with heavy anti-aircraft guns. One or two of the officers also stay with us. Thus I will see lots of people come to our house to bring information to these various military men, assured, no doubt, that each one of these will be able to tip them off to all the secrets of the E.M.3

Freddy and I are bewildered, and we also have a good laugh, not knowing which of these two sentiments takes precedence, for we are dumbfounded at the naiveté of these adults. I may be lying when I say that we are simply amused, without ever seeing the tragedy of the situation, but I think I can say without too much presumption that Freddy and I, who are barely 17, keep our sang froid better than many of these adults around us, whom, up till then, we more or less respected – my parents excepted, whom I secretly venerated, without ever telling them so. Perhaps, and I say it all the same, it was because of our young age, but the febricity of these people surprises us, alarms us!

We sleep a night or two in the cellar, in the shelter of the mattresses, conceding the bedrooms to the military. During those days Freddy and I make many friends among the Belgian and English soldiers, but we choose our friends among the troops, leaving the officers to my parents and the other adults. We invite them to join us for coffee, sometimes in the garden. During the night more than during the day, the anti-aircraft near the house keep us in suspense, interrupting our sleep.

On 13 May, the one of my two brothers who is in the 1st Lancers arrived, totally unexpected and to our great joy, coming from the Hautes – Fagnes.4 He and a comrade arrive in a “Marmon”,5 a sort of armored reconnaissance vehicle with rubber tires. Their unit is to reform at Meise, where they report immediately, returning in the evening to stay at the house.

Up till then I had a little admiration for Hitler as the result of certain writings vaunting his social and political achievements and, indirectly, as a result of my sympathy with Fascist Italy and Franco Spain. At the moment, for sure, my convictions were shaken, like those of others. Furthermore, the environment and the wild democratic propaganda bored us. For the sake of the cause they called on all the image d’Épinal,6 all the bedtime stories that the naive and children swallow without batting an eyelid, of children with their hands cut off, of couples tied back-to-back and thrown into the Meuse…

Our political leaders had, in the meantime, made it clear that every Rexist was to do his duty in the ranks of the army or at other posts. Thus it was with all the more astonishment that we then learned of the arrest of the Chef7 and of his ignominious deportation along with Joris Van Severen, the leader of the Verdinaso,8 and other sympathizers, but also people of all sorts of different political views. Among these deportees were militant communists, Jews and a great number of other people who had come from central Europe for all sorts of reasons. The “Authorities” of our country thus were guilty of the first deportations, well before the question of deportations by the enemy of the moment became a question. Worse yet, they were turned over to a country foreign to their own nationalities. I cannot find an example of another country that did this!

On 14 May, at 2200 hours, we leave our house intending to go to Portugal and, from there, perhaps, to the Congo, with a mattress on the roof of the automobile. I find, furthermore, that in time of war, this seems standard for all makes of automobiles, all models, including the bottom of the line! There are eight of us in the automobile: six adults, a little girl and myself. With some difficulty we find petrol and spend the night at Assche in a café where a great many refugees are already sleeping.

On the 15th we depart toward Ninove, then Tournai and Froidmont, where we spend the night at a farm. The roads are filled with all sorts of vehicles, as much civili...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Maps

- Author’s Notes

- Preface

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments and Sources

- Glossary

- Chapter 1: From Peace to War

- Chapter 2: Instruction (in Brandenburg)

- Chapter 3: En Route to the East: 16 Days on Straw

- Chapter 4: Slaviansk: The Front is Not Much Farther

- Chapter 5: The Advance

- Chapter 6: The Return of the Prodigal Son

- Chapter 7: Koubano – Armianski: Caucasus

- Chapter 8: Toward New Horizons

- Chapter 9: 21 October, 1942: Evacuated

- Chapter 10: Conclusion of the Campaign in the Caucasus: Prelude to Another

- Chapter 11: New Winter Campaign: Tcherkassy

- Chapter 12: Our Second Campaign: My First Winter

- Chapter 13: The Fighting at Teklino

- Chapter 14: The Encirclement

- Chapter 15: The Breakthrough: The Word is “Freiheit”!

- Chapter 16: The Tour of the Hospitals

- Chapter 17: Return on a “Mission” to Belgium

- Chapter 18: Exile

- Chapter 19: Return to My Unit

- Chapter 20: Departure for the Oder: The Final Endeavors

- Chapter 21: Ephemeral Prisoners

- Chapter 22: Our Return to Belgium

- Chapter 23: Arrested and a Captive in My Own Land

- Chapter 24: From Dampremy to St. Gilles

- Chapter 25: The “Petit Château”

- Chapter 26: The Tribunal

- Chapter 27: Beverloo

- Chapter 28: The Merksplas Colony

- Chapter 29: Shadow, Freedom, Rebirth

- Epilogue

- Appendices