eBook - ePub

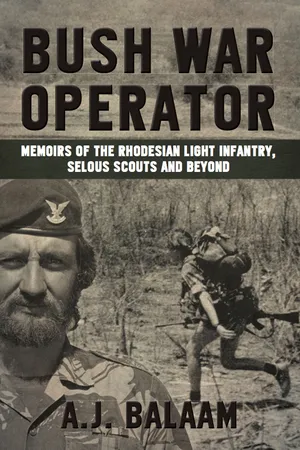

Bush War Operator

Memoirs of the Rhodesian Light Infantry, Selous Scouts and beyond

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"The finest account I've read on the Selous Scouts . . . Andy Balaam tells it like it was—the fear, the terror, the adrenaline highs of combat in the bush." —Chris Cocks, bestselling author of

Fireforce

From the searing heat of the Zambezi Valley to the freezing cold of the Chimanimani Mountains in Rhodesia, from the bars in Port St Johns in the Transkei to the Drakensberg Mountains in South Africa, this is the story of one man's fight against terror, and his conscience.

Anyone living in Rhodesia during the 1960s and 1970s would have had a father, husband, brother or son called up in the defense of the war-torn, landlocked little country. A few of these brave men would have been members of the elite and secretive unit that struck terror into the hearts of the ZANLA and ZIPRA guerrillas infiltrating the country at that time—the Selous Scouts. These men were highly trained and disciplined, with skills to rival the SAS, Navy Seals and the US Marines, although their dress and appearance were wildly unconventional: civilian clothing with blackened, hairy faces to resemble the very people they were fighting against.

Twice decorated—with the Member of the Legion of Merit (MLM) and the Military Forces' Commendation (MFC)—Andrew Balaam was a member of the Rhodesian Light Infantry and later the Selous Scouts, for a period spanning twelve years. This is his honest and insightful account of his time as a pseudo operator. His story is brutally truthful, frightening, sometimes humorous and often sad.

From the searing heat of the Zambezi Valley to the freezing cold of the Chimanimani Mountains in Rhodesia, from the bars in Port St Johns in the Transkei to the Drakensberg Mountains in South Africa, this is the story of one man's fight against terror, and his conscience.

Anyone living in Rhodesia during the 1960s and 1970s would have had a father, husband, brother or son called up in the defense of the war-torn, landlocked little country. A few of these brave men would have been members of the elite and secretive unit that struck terror into the hearts of the ZANLA and ZIPRA guerrillas infiltrating the country at that time—the Selous Scouts. These men were highly trained and disciplined, with skills to rival the SAS, Navy Seals and the US Marines, although their dress and appearance were wildly unconventional: civilian clothing with blackened, hairy faces to resemble the very people they were fighting against.

Twice decorated—with the Member of the Legion of Merit (MLM) and the Military Forces' Commendation (MFC)—Andrew Balaam was a member of the Rhodesian Light Infantry and later the Selous Scouts, for a period spanning twelve years. This is his honest and insightful account of his time as a pseudo operator. His story is brutally truthful, frightening, sometimes humorous and often sad.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Bush War Operator by A. J. Balaam in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Rhodesian Light Infantry, 1967–74

1

Kanyemba, Zambezi Valley, November 1967

“Jesus Christ,” I thought to myself, “what the fuck does this arsehole think he’s doing?”

It was hot, unbelievably hot, not a breath of air, not a bird in the sky, even the mopane flies had taken cover. The trees were leafless, their gaunt branches pointing up to the searing bright sky as if imploring the gods for rain. The grey-blue soil and rocks baked hard by the summer sun acted as one huge solar panel, absorbing the incredible heat produced by the glaring sun, and slowly releasing it as darkness fell, making sure the temperature never dropped below 30°C, day or night.

Into this mountainous, waterless, furnace walked ten members of Support Group, Rhodesian Light Infantry (RLI), loaded down like pack mules, practising patrol formations. And loaded down like pack mules we were. We had no lightweight equipment of any kind; the blankets you slept with in barracks were the same ones you took to the bush, heavy and cumbersome. All our webbing, British by design, was old and uncomfortable, especially the packs. Lacking a frame and having no padding on the straps, they were a mobile torture chamber. When loaded down with four days’ food, two blankets, hand grenades, trip flares and other odds and sods, it was not long before all the feeling in your arms was lost as the straps bit deep into your shoulder muscles, cutting off the blood supply.

Crouched under a leafless tree, head drooping, swearing at our patrol leader under my breath, soaking wet from sweat, arms hanging lifeless, I struggled to get my breathing under control and my heart felt as if it was going to burst. With my water bottle held in both shaking hands, I gulped down mouthful after mouthful, wasting just as much as I was drinking.

As far as I knew our task was simple. We were to ambush a group of terrorists who were supposed to be crossing the Zambezi River from Zambia into Rhodesia. The supposed crossing point was below a narrow gorge known as Hell’s Gate. Why we had been dropped at Kanyemba airstrip many hot, waterless, mountainous miles from the ambush point was beyond me, as was the reason we were practising patrol formations in the incredible heat.

Everything was grey, the trees, the rocks, the soil, the mountains and the sky, all grey and all encompassed in a glimmering heat haze. One look at the lifeless panorama spread out in front of us should have set the alarm bells ringing. It did not. We were young and stupid, led by equally young and stupid non-commissioned officers. Our knowledge of the bush and survival skills were limited to what we had learnt while growing up. At that stage, the Rhodesian army taught little or nothing on surviving under extreme conditions, but this patrol would change all that.

Looking around at my fellow patrol members, I could see they were suffering in the heat as much as I was – heads hanging, shirts unbuttoned and soaking wet from sweat, flushed faces, packs and webbing lying on the ground, weapons leaning up out of reach against trees or rocks, whichever was the closest. It was late afternoon. We had stopped at the bottom of a ridge in a small valley. That we were lost I did not doubt. The whole day the grey ridgelike steps had been leading us downward into the waterless hell of the Zambezi Valley itself. Everything looked the same. The one grey ridge looked the same as the next, as did the countless dry riverbeds. This was a map-reader’s nightmare. There was not a breath of air, not a bird in the sky, not an animal spoor on the game trail we were following, nothing, except the endless, mind-destroying screech of cicada beetles and the energy-sapping heat.

The practising of patrol formations had long since ceased. Bent over in order to try and relieve the pressure on my shoulders caused by the pack straps, I could see that, unfortunately, it was a case of too little too late. Looking around at my lifeless, exhausted, comrades, I could see the damage had already been done. Fighting back the urge to drink some of the warm water I had left in my water bottles, I walked over to where the patrol leader and several other sergeants were hunched over the map. There was much pointing at the map and the surrounding countryside, especially the ridges, which now hedged us in on all sides. I would have loved to have had a look at the map myself and offer an opinion. I had not been in the army long, but I already knew that to offer an opinion without being asked was a shortcut to trouble. I had offered a couple of uninvited opinions on my first recruit course: unfortunately they were not received in the spirit in which they were given, and I found myself failing my first recruit course. I had a bad attitude I was told. I was a barrack-room lawyer, a trouble-maker, who thought he was clever.

Slumping next to a nearby tree stump, I watched as our patrol leader tried in vain to contact our headquarters. This was day one, and already you could hear the frustration and uncertainty in his voice. This was not the parade ground where screaming and shouting were the order of the day and he reigned supreme. This was nature at its rawest – strong, unforgiving and relentless, where knowledge, strength and skill were required to survive. Unfortunately for us, time would prove that our patrol leader did not have the necessary attributes required to survive or guide others in such extreme conditions.

It was getting dark. The sunset was magnificent, the ridges and surrounding mountains glowed red and orange and the leafless trees seemed like fiery quills on the back of some kind of mystical porcupine. With drooping heads, dragging feet and bent backs, we were moving in single file, at a snail’s pace, along the game trail we had been following the whole day. It gets dark quickly in Africa. We were making one last attempt to find water before it got too dark to continue. It was a silent camp. Nobody was saying much. We were exhausted. The heat and the unforgiving terrain were bad enough – they would have sapped anybody’s strength – but the deciding factor between just being tired and exhausted was the stupid practising of patrol formations over such rugged country.

Lying on my blanket, staring up at the stars, listening to our patrol commander frantically trying to contact headquarters, I started to feel uneasy. Rolling over onto my side, I tried to get a look at my friends. It was too dark to see the expressions on their faces. The fact that they sat unmoving, faces turned, staring silently at the radio operator, spoke volumes. Rolling back onto my raw, skinless, throbbing back, I reached for my two water bottles. One was empty, the other three-quarters full. We were lost in some of the hottest, driest country in Rhodesia. It was uninhabited, apart from a few isolated villages of Batonka tribesmen. We had no radio communication with headquarters. And, worse, we had no water. No water, no life. A feeling of impending doom settled on me.

It had just started to get light and we were on the move. The night had been long, hot and sleepless, the stifling silence broken only by the opening and closing of water bottles and the occasional muffled groan of pain. My skin felt like it was on fire, my hands hung limply by my sides, my weapon too hot to hold was stuck in the front of my webbing. Staring unseeingly at my feet, I shuffled along. My head felt as if it was going to burst, my eyes were burning and dry and seemed set to pop out of my head. I was no longer sweating. My skin was cool and clammy. I was starting to dehydrate. I was no better or worse off than anybody else in the patrol. We were in big trouble. Without water we would all be dead in thirty-six hours.

I stumbled on. My ears were being battered by the ever-increasing screeching of the cicada beetles. To my tormented mind they sounded like the orchestra of death, playing the closing score to the final scene of a tragedy that was being played out in the grey shimmering theatre of death that was the Zambezi Valley.

Green trees! It could not be, I thought to myself. It must be a mirage.

The patrol ground to a halt as we stared in amazement. There, a hundred metres in front of us, through the shimmering heat haze, was a clump of green trees. God, everybody knew green trees meant water. Morale went through the sky and smiles were a dime a dozen. We were going to make it after all.

Thirty minutes later, with trembling hands, I slowly lifted my tin cup and sipped the urine mixed with lemonade powder. I had exchanged urine with my friend Vance Meyers. I had read somewhere that if you drank your own urine you would puke, but if you drank urine belonging to somebody else you had a better chance of keeping it down.

We had spent the last half an hour running up and down like headless chickens. We had arrived at the trees en masse, like a bunch of drunks, staggering and weaving all over the place, hope written over our blistered faces. Hope soon turned to dismay, the river was dry, there was no surface water, nothing, not a drop, and the sand was as dry as a bone. Some of the hardier members of the patrol tried digging, using their mess tins, but soon gave up, as no matter where they tried or how deep they dug, the sand remained dry.

The liquid concoction tasted awful and smelled even worse. My throat was dry and swollen. Swallowing was difficult – more of the mixture ran down onto my clothes than went down my throat. Did it help? I do not know. It was boiling hot, but my skin was dry, I was no longer sweating as there was no more fluid in my body to sweat out. The exposed skin on my arms, legs, face and neck was covered in a thin layer of salt, the last of my body’s reserves, and black ash from the burnt grass and trees. The deep cuts on my legs and hands had stopped bleeding as had the many grazes. I was on my last legs – another twenty-four hours without water and I would be dead, cooked in my own skin by my over-heating body. My brain was sluggish, tired and confused and I was having difficulty in making sense of what I was seeing and hearing. I had lost all sense of time and feeling. I did not know how long we had been wandering around lost and dying of thirst in this hell on earth.

We were on the move again. The heat was terrifying as it reflected off the surrounding ridges into our small valley, turning it into an oven. Using my weapon as a crutch, I managed to haul myself to my feet. One fall followed the next, getting to my feet took longer and longer. I felt nothing, I heard nothing. My head hung limply on my chest and my eyes stared blackly at the ground in front of me. I was no longer a thinking, caring human being; I was just an animal trying to survive.

Several hours later, after having split up into small groups to search for water, I was squatting under a tree, my shirt piled on top of my webbing, rifle and pack. I stared around. My whole being was concentrated on survival; anything else, even the thought of dying, brought no reaction from my boiling brain. It was all about survival. All I could think about was getting out alive. How much longer I could last I did not know. I could still stand up, maybe a bit unsteadily on my feet, but I could stand, my walk was more of shuffle, but I could still move. I was in fact a lot better off than many of my comrades, several of whom had lapsed into a semi-coma.

Sitting under the trees, my head on my knees, I waited for it to get dark and cool down a bit. What I was going to do after the darkness descended and it cooled down I did not know. It just seemed to be the right thing to do.

2

Chewore Wilderness Area, Zambezi Valley, 1972

After two days of travelling by Land Rover and Ford F250 trucks over some of the worst roads in Africa, we finally arrived at our destination: the Chewore Wilderness Area. Situated between the Zambezi River that marked the border between Zambia and Rhodesia, and the Zambezi escarpment, it was famous for its vast herds of buffalo, abundant rhino, lion, leopard, elephant and most forms of African wildlife. Basically untouched, except for the odd hunting camp and game ranger’s house, it was how Africa had been before the arrival of the white man with his guns and his lust for blood. I had been looking forward to this trip for weeks. The fishing, the game-viewing, the hot springs, the fresh meat and with a bit of crocodile hunting thrown in on the side, it made this one of my favourite areas in which to base up. As I sat in the warm sun waiting for our troop sergeant to select an area to set up a camp, I remembered only the good: the fishing, the shooting, the bathing in the hot springs. I...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of photographs

- List of maps

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Maps

- Prologue

- Part 1: Rhodesian Light Infantry, 1967–74

- Part 2: Selous Scouts, 1975–80

- Part 3: South Africa: Homeland Security, 1982–88

- eBooks Published by Helion & Company